The Vitality and Livability of Small Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0:04:09 When Should Seniors Hang Up The Car Keys? Age Talk Of The Nation 10/15/2012 0:30:20 Taking The Car Keys Away From Older Drivers Age All Things Considered 10/16/2012 0:05:29 Home Health Aides: In Demand, Yet Paid Little Age Morning Edition 10/17/2012 0:04:04 Home Health Aides Often As Old As Their Clients Age Talk Of The Nation 10/25/2012 0:30:21 'Elders' Seek Solutions To World's Worst Problems Age Morning Edition 11/01/2012 0:04:44 Older Voters Could Decide Outcome In Volatile Wisconsin Age All Things Considered 11/01/2012 0:03:24 Low-Income New Yorkers Struggle After Sandy Age Talk Of The Nation 11/01/2012 0:16:43 Sandy Especially Tough On Vulnerable Populations Age Fresh Air 11/05/2012 0:06:34 Caring For Mom, Dreaming Of 'Elsewhere' Age All Things Considered 11/06/2012 0:02:48 New York City's Elderly Worry As Temperatures Dip Age All Things Considered 11/09/2012 0:03:00 The Benefit Of Birthdays? Freebies Galore Age Tell Me More 11/12/2012 0:14:28 How To Start Talking Details With Aging Parents Age Talk Of The Nation 11/28/2012 0:30:18 Preparing For The Looming Dementia Crisis Age Morning Edition 11/29/2012 0:04:15 The Hidden Costs Of Raising The Medicare Age Age All Things Considered 11/30/2012 0:03:59 Immigrants Key To Looming Health Aide Shortage Age All Things Considered 12/04/2012 0:03:52 Social Security's COLA: At Stake In 'Fiscal Cliff' Talks? Age Morning Edition 12/06/2012 0:03:49 Why It's Easier To Scam The Elderly Age Weekend Edition Saturday 12/08/2012 -

Northeast Arkansas Edition DECEMBER 2020-2021

Find It Here. Northeast Arkansas Edition DECEMBER 2020-2021 We’re on the web! Use our online directory at Ritter411.com 870.358.4400 rittercommunications.com Emergency & Information Numbers Write in the telephone numbers you will need in case of an emergency. Obtain your Police and Fire Department numbers from the list below. Local Police _________________________________ Doctor _______________ State Police _________________________________ Ambulance _______________ Fire _________________________________ ________ In counties where enhanced 9-1-1 service is not available, calls are transferred to a local law enforcement agency. Police Marked Tree . Dial 358-2024 Lepanto . Dial 475-2566 Tyronza . Dial 487-2168 Keiser . Dial 526-2300 Dyess . Dial 764-2101 Etowah . Dial 531-2340 Fire Marked Tree . Dial 358-3131 Lepanto . Dial 475-6030 Tyronza . Dial 487-2103 Keiser . Dial 526-2300 Dyess . Dial 764-2211 Etowah . Dial 531-2540 Sheriff Department Poinsett County . .(Toll Call) 1-870-578-5411 Mississippi County . .(Toll Call) 1-870-658-2242 1 How To Reach Us Cable Location – Call us Before you Dig Before you dig in areas where telephone cables are buried, please call our repair service first at 1-888-336-4466 or the Arkansas One Call System at 811 or 1-800-482-8998 where the personnel will locate any cables in the area free of charge. A cut cable causes trouble, added costs and service blackouts. The calls and conversations you cut off can be someone with a health emergency trying to get aid, someone trying to reach the fire or police department or a customer with an important business call. -

Alliance of Arkansas 2013 Arkansas Preservation Awards Program Reception

Historic Alliance of Arkansas 2013 Arkansas Preservation Awards Program Reception Welcome Courtney Crouch III / President, Historic Preservation Alliance Dinner Remarks John T. Greer Jr., AIA, LEED AP / Past President and Awards Selection Committee Chair Awards Program Rex Nelson, Master of Ceremonies Awards presented by Courtney Crouch III Closing Remarks Vanessa McKuin / Executive Director, Historic Preservation Alliance Sponsors & Patrons Special Thanks Bronze Sponsors Special thanks to: Holly Frein Parker Westbrook Laura Gilson Missy McSwain Table Sponsors Caroline Millar Greg Phillips Susan Shaddox Cary Tyson Amara Yancey Additional Table Sponsors Courtney Crouch Jr. & Brenda Crouch Ann McSwain Patrons Ted & Leslie Belden Brister Construction Richard C. Butler Jr. William Clark, Clark Contractors W.L. Cook Courtney C. Crouch III & Amber Crouch Energy Engineering Consultants Senator Keith Ingram Representative Walls McCrary and Emma McCrary The Honorable Robert S. Moore and Beverly Bailey Moore Justice and David Newbern Mark and Cheri Nichols WER Architects/Planners Additional support provided by: Theodosia Murphy Nolan Golden Eagle of Arkansas Lifetime Achievement Award Recipients Named in honor of the Alliance’s Founding President, the Parker Westbrook Parker Westbrook Award for Lifetime Achievement Award recognizes significant individual achievement in historic preservation. It is Award – Frances “Missy” McSwain, Lonoke the Alliance’s only award for achievement in preservation over a period of years. The award may be presented to an individual, organization, business or public Excellence in Heritage Preservation Award agency whose activity may be of local, statewide or regional importance. Award – Delta Cultural Center, Helena Recipients of the Parker Westbrook Award for Lifetime Achievement Excellence in Preservation through Rehabilitation 1981 Susie Pryor, Camden Award – Fort Smith Regional Art Museum, Fort Smith Large Project – Mann on Main, Little Rock Edwin Cromwell, Little Rock 1982 Small Project – Lesmeister Guesthouse, Pocahontas 1983 Dr. -

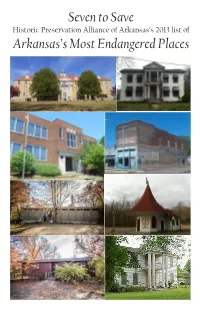

2013 MEP Press Packet

Seven to Save Historic Preservation Alliance of Arkansas’s 2013 list of Arkansas’s Most Endangered Places About the Most Endangered Places Program The Historic Preservation Alliance of Arkansas began Arkansas’s Most Endangered Places program in 1999 to raise awareness of the importance of Arkansas’s historic properties and the dangers they face through neglect, encroaching development, and loss of integrity. The list is updated each year and serves to generate discussion and support for saving the state’s endangered historic places. Previous places listed include the Johnny Cash Boyhood Home and the Dyess Colony Administration Building in Dyess, Bluff Shelter Archaeological Sites in Northwest Arkansas, Rohwer and Jerome Japanese-American Relocation Camps in Desha County, the William Woodruff House in Little Rock, Magnolia Manor in Arkadelphia, Centennial Baptist Church in Helena, the Donaghey Buildings in Little Rock, the Saenger Theatre in Pine Bluff, the twentieth century African American Rosenwald Schools throughout the state, the Mountainaire Apartments in Hot Springs, Forest Fire Lookouts statewide, the Historic Dunbar Neighborhood in Little Rock, Carleson Terrace in Fayetteville, the Woodmen on Union Building in Hot Springs. Properties are nominated by individuals, communities, and organizations interested in preserving these places for future Arkansans. Criteria for inclusion in the list includes a property’s listing or eligibility for listing in the Arkansas or National Register of Historic Places; the degree of a property’s local, state or national significance; and the imminence and degree of the threat to the property. The Historic Preservation Alliance of Arkansas was founded in 1981 and is the only statewide nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving Arkansas’s architectural and cultural heritage. -

September 2012

Celebrating Rural Money Trumps Easy Back-To-School Electrification p. 4 Tradition p. 24 Recipes p. 34 www.ecark.org SEPTEMBER 2012 Lee & BertheLLa $$50,00050,000 thomas Energy Efficiency Grand Prize Winners MAKEMAKEOOVEVERR SEPTEMBER 2012 ARKANSAS LIVING I 1 WATERFURNACE UNITS QUALIFY FOR A 30% FEDERAL TAX CREDIT and it isn’t just corn. You may not realize it, but your home is sitting on a free and renewable supply of energy. A WaterFurnace geothermal comfort system taps into the stored solar energy in your own backyard to provide savings of up to 70% on heating, cooling and hot water. That’s money in the bank and a smart investment in your family’s comfort. Contact your local WaterFurnace dealer today to learn how to tap into your buried treasure. YOUR LOCAL WATERFURNACE DEALERS Brookland DeQueen Mountain Home Russellville Nightingale Mechanical Bill Lee Co. Custom Heating & Cooling Rood Heating & Air (870) 933-1200 (870) 642-7127 (870) 425-9498 (479) 968-3131 Cabot Hot Springs Central Heating & Air Springdale Stedfast Heating & Air GTS Inc. (870) 425-4717 Paschal Heat, Air & (501) 843-4860 (501) 760-3032 Plumbing (800) 933-0195 waterfurnace.com (800) GEO-SAVE 2 I ARKANSAS LIVING ©2012 WaterFurnace is a registered trademark of WaterFurnace International, Inc. SEPTEMBER 2012 WATERFURNACE UNITS QUALIFY FOR A 30% FEDERAL TAX CREDIT (ISSN 0048-878X) (USPS 472960) Arkansas Living is published monthly. CONTENTS Periodicals postage paid at Little Rock, AR and at additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: Arkansas Living, P.O. Box 510, Little Rock, AR 72203 Members: Please send name of your cooperative with mailing label. -

Delta Sources and Resources ...134 Reviews

Delta Sources and Resources . 134 The King Biscuit Blues Festival (Helena, Arkansas) by LaDawn Fuhr Reviews . 137 Epps, Slavery on the Periphery: The Kansas-Missouri Border in the Antebellum and Civil War Eras, reviewed by Carl Moneyhon Nabors, From Oligarchy to Republicanism: The Great Task of Reconstruction, reviewed by William H. Pruden III Gordon, The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition; and Harcourt, Ku Klux Kulture: America and the Klan in the 1920s, reviewed by Kenneth C. Barnes Cox, Goat Castle: A True Story of Murder, Race, and the Gothic South, reviewed by Colin Woodward Ossad, Omar Nelson Bradley: America’s GI General, reviewed by Keith M. Finley Devlin, Remember Little Rock, reviewed by Misti Nicole Harper Ward, Out in the Rural, reviewed by Anthony B. Newkirk Bales, ed., Willie Morris: Shifting Interludes, reviewed by Barclay Key Osing, May Day, reviewed by Lynn DiPier Berard, Water Tossing Boulders: How A Family of Chinese Immigrants Led the First Fight to Desegregate Schools in the Jim Crow South, reviewed by Doreen Yu Dong Mitchell, Unnatural Habitats & Other Stories, reviewed by Janelle Collins Ferris, The South in Color: A Rural Journal, reviewed by Marcus Charles Tribbett Contributors . 158 ___________________________________________________________________________________ Arkansas Review 49.2 (August 2018) 82 Reviews Slavery on the Periphery: The in the creation of a world different from that Kansas-Missouri Border in the An- each brought to the confrontation. Addition- ally, she is influenced by the rhetoric of histori- tebellum and Civil War Eras. By ans concerned with social justice. -

Arkansas Public Higher Education Operating & Capital

Arkansas Public Higher Education Operating & Capital Recommendations 2019-2021 Biennium 7-A Volume 1 Universities Arkansas Department of Higher Education 423 Main Street, Suite 400, Little Rock, Arkansas 72201 October 2018 ARKANSAS PUBLIC HIGHER EDUCATION OPERATING AND CAPITAL RECOMMENDATIONS 2019-2021 BIENNIUM VOLUME 1 OVERVIEW AND UNIVERSITIES TABLE OF CONTENTS INSTITUTIONAL ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................................................... 1 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR EDUCATIONAL AND GENERAL OPERATIONS ................................................................................... 3 Background ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Table A. Summary of Operating Needs & Recommendations for the 2019-2021 Biennium .............................................................. 7 Table B. Year 2 - Productivity Index ................................................................................................................................................. 8 Table C. 2019-21 Four-Year Universities Recommendations ........................................................................................................... 9 Table D. 2019-21 Two-Year Colleges Recommendations .............................................................................................................. 10 Table E. 2019-21 -

City & Town, January 2016 Vol. 72, No. 01

JANUARY 2016 VOL. 72, NO. 01 THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE ARKANSAS MUNICIPAL LEAGUE REAL BANKERS for REAL PEOPLE Bob Birch, Regional President; Gordon Silaski, Division President; Kim Pruitt., Senior Business Development Officer; Jose Hinojosa, Regional Retail Leader; Jeff Hildebrand, Chief Lending Officer, NMLS 675428. More than just bankers, we are your neighbor. It’s OUR goal to help you meet YOUR financial goals. Your business should be built on a strong banking relationship and a solid financial foundation. Let us help you start, grow, or expand your business. MY100BANK.COM 501-603-3849 A Home BancShares Company MUNICIP S AL A L S E N A A G K U R E A ARKANSAS MUNICIPAL LEAGUE G GREAT CITIES MAKE A GREAT STATE E R T E A A T T S C T I A TI E ES GR MAKE A ON THE COVER—With the recent U.S. Supreme Court decision in Reed v. Town of Gilbert, Arizona, cities must make adjustments to their sign codes. Read about the decision and what you need to do inside on page 6. Read also about Arkansas statutes governing record retention, helpful tips for better police-community relations, Jonesboro’s new police training Cover photo by program, and more.—atm Andrew Morgan Features City & Town Contents Court’s decision means revisiting sign Arkansas Municipal League Officers ..........5 6 codes Calendar .............................................19 Cities must take another look at their sign Economic Development ..........................32 codes governing content after the U.S. Engineering ..........................................36 Supreme Court’s decision in Reed v. Town of Gilbert, Arizona. -

Arkansas State University, State University, AR

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Challenge Grants application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/challenge/challenge-grants for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Office of Challenge Grants staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Historic Dyess Colony: A New Deal Farm Experiment Institution: Arkansas State University, State University, AR Project Directors: Dr. Ruth A. Hawkins Grant Program: Challenge Grants 400 7th Street, SW, Washington, DC 20024 P 202.606.8309 F 202.606.8394 E [email protected] www.neh.gov National Endowment for the Humanities Challenge Grant Historic Dyess Colony A New Deal Farm Experiment Table of Contents Abstract 1 Grant Budget 2 Institutional Fact Summary 4 Institutional Financial Summary 5 Project Narrative A. Introduction 7 B. Arkansas State University's Place in the Delta 8 C. Agricultural Heritage 9 D. The Lakeport Plantation 11 E. Southern Tenant Farmers Museum 12 F. -

2019 Johnny Cash Heritage Festival ARTS and CRAFTS VENDOR INFORMATION

2019 Johnny Cash Heritage Festival ARTS AND CRAFTS VENDOR INFORMATION October 17-19, 2019, are the dates for our 3rd Annual Johnny Cash Heritage Festival (JCHF) in Dyess, Arkansas. This festival celebrates the legacy of Johnny Cash, along with the agricultural resettlement colony and other New Deal programs of the 1930s. We are pleased to invite you to apply as an arts and crafts vendor on Thursday, October 17 and Friday, October 18, in the Dyess Colony Circle and/or on Saturday, October 19, 2019, in the field adjacent to the Cash house and site of the concert. This three-day festival will begin at 9 a.m. on Thursday, Oct. 17, with a symposium in the Dyess Colony Visitors Center (located in the Colony Circle) that continues all day Friday. Regional music will be performed in the Colony Center on Thursday and Friday evenings until 9 p.m. Arts and crafts vendors and demonstrations will be held on Friday in the Colony Circle. On Saturday, major music events will begin at noon in the field adjacent to the Cash Home. Rosanne Cash and Marty Stuart will headline the music for the day along with other performers and Cash family members. Gates for Field Concert performances will open at 11 a.m. and close at 6 p.m. Thus, the festival offers two opportunities for arts and crafts vendors: • Colony Center from 9 a.m. until 9 p.m. Thursday, October 17 and Friday, Oct. 18. (Must remain all day. NO EARLY DEPARTURES). • Cash Farmstead Field from 11 a.m. -

Delta Sources and Resources

Delta Sources and Resources Johnny Cash Boyhood Home / story of the 500 families who came to Dyess Historic Dyess Colony Colony, the largest and one of the earliest agri - cultural resettlement communities designed to 110 Center Drive alleviate rural poverty under Franklin D. Roo - Dyess, Arkansas sevelt’s New Deal. by Amy Ulmer Several economic and natural disasters caused the need for resettlement communities Many visitors to the Historic Dyess in the United States, especially in the South. Colony: Johnny Cash Boyhood Home expect In Arkansas, the twenties were anything but to learn a little about the “Man in Black.” They “roaring.” The state had been in recession are often surprised to discover the depth and nearly a decade before the Great Depression hit. Johnny Cash Boyhood Home Photograph courtesy of Ruth Hawkins richness of the history presented at the heritage After the flood of 1927 devastated the land and site established by Arkansas State University. its people, a year-long drought starting in 1930 The site tells a larger story—one often over - hit Arkansas harder than any of the twenty-two shadowed by Cash’s rise to fame and struggles states affected. In addition, the stock market with drug addiction, and one different from the crash of 1929 led to bank closures across the rags-to-riches narrative that Johnny never ap - state. By the end of 1930, approximately two- preciated. The ASU Heritage Site also tells the thirds of Arkansas’s independent farmers had ___________________________________________________________________________________ 42 lost their farms. administrative workers on the colony, as well as When President Roosevelt took office in the Theatre. -

January 2015 Vol

JANUARY 2015 VOL. 71, NO. 01 THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE ARKANSAS MUNICIPAL LEAGUE Don’t miss the 2015 Winter Conference January 14-16 in Little Rock Download our free mobile app for locations throughout the Natural State. 1 Bentonville Mountain Home Rogers 1 Rector 1 2 1 Springdale Highland 1 1 Paragould Tontitown Mountain View 2 3 2 2 Siloam Fayetteville Monette Springs Batesville 1 Heber Springs 2 7 Van Buren 1 1 Clarksville Jonesboro 1 1 Greenbrier Russellville 1 Quitman 3 Atkins Searcy 3 1 Morrilton 3 Fort 1 1 Smith 1 7 1 2 Dardanelle Pottsville Beebe Conway Vilonia 1 Ward 1 5 Mayflower 3 Cabot Jacksonville 1 1 Maumelle Sherwood 5 North Little Rock 8 Bryant Little Rock 1 Fordyce 1 FOR ALL YOUR BANKING NEEDS, INCLUDING: BUSINESS & INVESTMENT INSURANCE PERSONAL LOANS SERVICES SERVICES MY100BANK.COM 888-372-9788 A Home BancShares Company ARKANSAS MUNICIPAL LEAGUE GREAT CITIES MAKE A GREAT STATE ON THE COVER—The lights of downtown Little Rock reflect in the water of the Arkansas River on a recent, chilly evening. We look forward to seeing you downtown for the League’s 2015 Winter Conference, Jan. 14-16, where we’ll prep for the 90th General Assembly and a great year for Arkansas municipalities. See page 24 in this issue to register if you haven’t already. Cover photo by Read also inside tips for newly elected officials, advice for communicating with legislators, an Andrew Morgan overview of laws governing records retention, and much more.—atm Features City & Town Contents Animal Control .....................................36 Tips