Supermajority Provisions, Guinn V. Legislature and a Flawed Constitutional Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

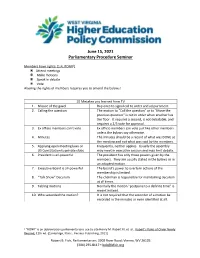

June 15, 2021 Parliamentary Procedure Seminar

June 15, 2021 Parliamentary Procedure Seminar Members have rights: [1:4, RONR1] Attend meetings Make motions Speak in debate Vote Altering the rights of members requires you to amend the bylaws! 10 Mistakes you learned from TV 1. Misuse of the gavel Rap once to signal call to order and adjournment. 2. Calling the question The motion to “Call the question” or to “Move the previous question” is not in order when another has the floor. It requires a second, is not debatable, and requires a 2/3 vote for approval. 3. Ex officio members can’t vote Ex officio members can vote just like other members unless the bylaws say otherwise. 4. Minutes The minutes should be a record of what was DONE at the meeting and not what was said by the members. 5. Applying open meeting laws or Frequently, neither applies. Usually the assembly US Constitution to private clubs may meet in executive session and may limit debate. 6. President is all-powerful The president has only those powers given by the members. They are usually stated in the bylaws or in an adopted motion. 7. Executive Board is all-powerful The board’s power to overturn actions of the membership is limited. 8. “Talk Show” Decorum The chairman is responsible for maintaining decorum at all times. 9. Tabling motions Normally the motion “postpone to a definite time” is meant instead. 10. Who seconded the motion? It is not required that the seconder of a motion be recorded in the minutes or even identified at all. 1 “RONR” is an abbreviation parliamentarians use to cite Henry M. -

Parliamentary Principles

Parliamentary Principles . All delegates have equal rights, privileges and obligations . The majority vote decides. The rights of the minority must be protected. Full and free discussion of every proposition presented for decision is an established right of delegates. Every delegate has the right to know the meaning of the question before the assembly and what its effect will be. All meetings must be characterized by fairness and by good faith. Basic Rules of Motions 1. Motions have a definite order of precedence, each motion having a fixed rank for its introduction and consideration. 2. ONLY ONE MOTION MAY BE CONSIDERED AT A TIME. 3. No main motion can be substituted for another main motion EXCEPT that a new main motion on the same subject may be offered as a substitute amendment to the main motion. 4. All motions require a second to begin discussion unless it is from a delegation or committee or it is a simple request such as a question of privilege, a point of order or division. AMENDMENTS FOUR WAYS TO AMEND A MAIN MOTION 1. Amend by addition 2. Amend by deletion 3. Amend by addition and deletion 4. Amend by substitution TWO ORDERS OF AMENDMENTS 1. First order is an amendment to the original resolution 2. Second order is an amendment to the first order amendment. 3. No more than one order of amendment is discussed at the same time. Voting on Motions Majority vote: the calculation of the vote is based on the number of members present and voting or a majority of the legal votes cast ; abstentions are not counted; delegates who fail to vote are presumed to have waived the exercise of their right; applies to most motions Two-Thirds vote : a supermajority 2/3 vote is required when the vote restricts the right of full and free discussion: This includes a vote to TABLE, CLOSE DEBATE, LIMIT/EXTEND DEBATE, as well as to SUSPEND RULES. -

Proxy Voting Guidelines Benchmark Policy Recommendations TITLE

UNITED STATES Proxy Voting Guidelines Benchmark Policy Recommendations TITLE Effective for Meetings on or after February 1, 2021 Published November 19, 2020 ISS GOVERNANCE .COM © 2020 | Institutional Shareholder Services and/or its affiliates UNITED STATES PROXY VOTING GUIDELINES TABLE OF CONTENTS Coverage ................................................................................................................................................................ 7 1. Board of Directors ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Voting on Director Nominees in Uncontested Elections ........................................................................................... 8 Independence ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 ISS Classification of Directors – U.S. ................................................................................................................. 9 Composition ........................................................................................................................................................ 11 Responsiveness ................................................................................................................................................... 12 Accountability .................................................................................................................................................... -

Motions Explained

MOTIONS EXPLAINED Adjournment: Suspension of proceedings to another time or place. To adjourn means to suspend until a later stated time or place. Recess: Bodies are released to reassemble at a later time. The members may leave the meeting room, but are expected to remain nearby. A recess may be simply to allow a break (e.g. for lunch) or it may be related to the meeting (e.g. to allow time for vote‐counting). Register Complaint: To raise a question of privilege that permits a request related to the rights and privileges of the assembly or any of its members to be brought up. Any time a member feels their ability to serve is being affected by some condition. Make Body Follow Agenda: A call for the orders of the day is a motion to require the body to conform to its agenda or order of business. Lay Aside Temporarily: A motion to lay the question on the table (often simply "table") or the motion to postpone consideration is a proposal to suspend consideration of a pending motion. Close Debate: A motion to the previous question (also known as calling for the question, calling the question, close debate and other terms) is a motion to end debate, and the moving of amendments, on any debatable or amendable motion and bring that motion to an immediate vote. Limit or extend debate: The motion to limit or extend limits of debate is used to modify the rules of debate. Postpone to a certain time: In parliamentary procedure, a postponing to a certain time or postponing to a time certain is an act of the deliberative assembly, generally implemented as a motion. -

Advisory Committee Meeting Minutes

Advisory Committee Meeting Minutes In order to have a record of meetings it is important to take minutes of the meeting. Many automotive instructors are unsure what should be included in the minutes and how much detail is required for future reference. Keep in mind that the minutes are a formal record of the meeting and should provide enough information so that anyone could review them and have a good understanding of the issues, the discussion, and the actions taken. It’s helpful to have an agenda for your meeting to move the meeting along smoothly. At a minimum, the following information should be included in the Advisory Committee meeting minutes: 1. Date, location, and time 2. List of members who attend and members who are absent 3. Old Business – review and approval of minutes from the last meeting 4. Discuss agenda items – summarize the discussion of each of the topics. If there was a motion for action, record who made and who seconded the motion as well as the results of the vote. 5. New Business (if any) 6. Set a date for the next meeting 7. Note the time of adjournment Please remember the NATEF Standards require that Advisory Committees review and provide input on programs. A summary of the specific standards that Advisory Committees should review are listed in Procedures Section in the Program Standards. Make sure that your minutes reflect a review of these topics. All these items may not be reviewed during the same meeting, but they must be reviewed. Meeting minutes may be recorded by anyone at the meeting, but the person responsible for conducting the meeting should not be responsible for recording the minutes. -

Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics Economics 2005 Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/law_and_economics Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Adrian Vermeule, "Absolute Voting Rules" (John M. Olin Program in Law and Economics Working Paper No. 257, 2005). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Economics by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHICAGO JOHN M. OLIN LAW & ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER NO. 257 (2D SERIES) Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule THE LAW SCHOOL THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO August 2005 This paper can be downloaded without charge at: The Chicago Working Paper Series Index: http://www.law.uchicago.edu/Lawecon/index.html and at the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=791724 Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule* The theory of voting rules developed in law, political science, and economics typically compares simple majority rule with alternatives, such as various types of supermajority rules1 and submajority rules.2 There is another critical dimension to these questions, however. Consider the following puzzles: $ In the United States Congress, the votes of a majority of those present and voting are necessary to approve a law.3 In the legislatures of California and Minnesota,4 however, the votes of a majority of all elected members are required. -

Simplified Parliamentary Procedure

Extension to Communities Simplifi ed Parliamentary Procedure 2 • Iowa State University Extension Introduction Effective Meetings — Simplifi ed Parliamentary Procedure “We must learn to run a meeting without victimizing the audience; but more impor- tantly, without being victimized by individuals who are armed with parliamentary procedure and a personal agenda.” — www.calweb.com/~laredo/parlproc.htm Parliamentary procedure. Sound complicated? Controlling? Boring? Intimidating? Why do we need to know all those rules for conducting a meeting? Why can’t we just run the meetings however we want to? Who cares if we follow parliamentary procedure? How many times have you attended a meeting that ran on and on and didn’t accomplish anything? The meeting jumps from one topic to another without deciding on anything. Group members disrupt the meeting with their own personal agendas. Arguments erupt. A few people make all the decisions and ignore everyone else’s opinions. Everyone leaves the meeting feeling frustrated. Sound familiar? Then a little parliamentary procedure may just be the thing to turn your unproductive, frustrating meetings into a thing of beauty — or at least make them more enjoyable and productive. What is Parliamentary Procedure? Parliamentary procedure is a set of well proven rules designed to move business along in a meeting while maintaining order and controlling the communications process. Its purpose is to help groups accomplish their tasks through an orderly, democratic process. Parliamentary procedure is not intended to inhibit a meeting with unnecessary rules or to prevent people from expressing their opinions. It is intended to facilitate the smooth func- tioning of the meeting and promote cooperation and harmony among members. -

Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee April 27–28, 2021

_____________________________________________________________________________________________Page 1 Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee April 27–28, 2021 A joint meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee Ann E. Misback, Secretary, Office of the Secretary, and the Board of Governors was held by videoconfer- Board of Governors ence on Tuesday, April 27, 2021, at 9:30 a.m. and con- tinued on Wednesday, April 28, 2021, at 9:00 a.m.1 Matthew J. Eichner,2 Director, Division of Reserve Bank Operations and Payment Systems, Board of PRESENT: Governors; Michael S. Gibson, Director, Division Jerome H. Powell, Chair of Supervision and Regulation, Board of John C. Williams, Vice Chair Governors; Andreas Lehnert, Director, Division of Thomas I. Barkin Financial Stability, Board of Governors Raphael W. Bostic Michelle W. Bowman Sally Davies, Deputy Director, Division of Lael Brainard International Finance, Board of Governors Richard H. Clarida Mary C. Daly Jon Faust, Senior Special Adviser to the Chair, Division Charles L. Evans of Board Members, Board of Governors Randal K. Quarles Christopher J. Waller Joshua Gallin, Special Adviser to the Chair, Division of Board Members, Board of Governors James Bullard, Esther L. George, Naureen Hassan, Loretta J. Mester, and Eric Rosengren, Alternate William F. Bassett, Antulio N. Bomfim, Wendy E. Members of the Federal Open Market Committee Dunn, Burcu Duygan-Bump, Jane E. Ihrig, Kurt F. Lewis, and Chiara Scotti, Special Advisers to the Patrick Harker, Robert S. Kaplan, and Neel Kashkari, Board, Division of Board Members, Board of Presidents of the Federal Reserve Banks of Governors Philadelphia, Dallas, and Minneapolis, respectively Carol C. Bertaut, Senior Associate Director, Division James A. -

Constitutions and Elections

Section II CONSTITUTIONS AND ELECTIONS \ K 1. Constitutions 2. Elections A J' - -.: \ \ ' '"' •• • 1 • . .1 \ • i • . • • • - • ® •;;/ : ; *k*.«ii«'tt*S'*fVT' fX • \ A-. .J- .. - —-» .t. ^,^ a ^ '•^'•'^ / lSh • r- 7 1 • • ^r. <C-1 . Constitutions STATE CONSTITUTIONS AND CONSTITUTIONAL REYISION--JULY, 19.51-JUNE, 1953* r I fHE LONG ERA in which most state rather than on the first day of the biennial I ; constitutions. have remained little session of the General Assembly in Janu -^ changed continues. Orie-Xourth, of ary. This was necessary in order to avoid the exfeting constitutions were framed prior a repetition of time-consuming contests —in some cases long prior—to 1870. One- over certification in a divided legislature. half were framed betweenil 870 and 1900. These questions were-submitted to the " .One-fourth have emerged since 1^0 and electorate at^a special election held Jifce only four of these in the last fifteen years. 22, 1953, at which there was a very light The. avejrage .age of the forty-eight consti votie—only about 3 pen^cent or approxi tutions in 1953 came to seventy-eight and mately 35,000 of the state's 1,185,000 vot one-half years. ers. Both proposals received the over- Constitutional amendments were adopt whielming endorsement of those who voted.^ ed in more than half oT the states during the period from mid-1951 to mid-1953. FLORIDA Many of these were .limited in-scope. The 1951 Florida legislature proposed Summaries for several states in which ac eleven aniendments. Of these, only one tion was extensive appear below. -

“The House Rules Committee” Prof

“The House Rules Committee” Prof. Anthony Madonna POLS 4600 Maymester 5/20/2020 University of Georgia House Leaders and Committees: Outline 5/20/2020 Introduction Assorted House Floor a. Updates Issues b. Summary Section a. Rule Alternatives: c. Hastert Rule Suspension d. 2017 American Health Care Act b. Floor Consideration Data c. Committee of the Whole “Regular Order,” d. Points of Order Amendments and Leaders a. Rules Types over Time Part 2: Committee- b. Rules Committee and Marijuana Gatekeeper Games c. Overview of the Rules Committee Rule Types a. Open b. Modified-Open c. Closed d. Modified Closed e. Structured Rules Oddities a. Waiver Only b. Self-Executing c. Martial Law d. King of the Hill 2 e. More Votes POLS 4600: Updates (5/20) ASSIGNMENTS: Civil Rights Act of 1957 and Telecommunications Act of 1996 are the last two I’m working through. SUMMARY SECTION: Summary Section is DUE on Sunday, May 24th. If you turn it in early, great! I can get your grade back quicker and you can get started on the background section. Section is discussed in greater detail in the next slide. VIDEOS: Coming along slowly. Don’t hesitate to use selectively. EXAM: This Friday. Would you prefer to take the evening? Above: Another poor choice. Things it will cover: Cooper and Brady, House Rules Committee, Using Resources, Ideological Scaling, How a Bill Becomes a Law, Constitutional Foundations of Congress, Parties and Leaders. Pay particular attention to the Resources. EMAILS: Behind. But I’ll have them to you Summary Section SUMMARY SECTION: STRUCTURE Give a brief one-three paragraph overview of the measure. -

Delegate Manual

AN IMPORTANT NOTE: ONLINE PROGRAMS ............................ 3 PROGRAM OVERVIEW .................................................................. 4 Introduction 4 Boys’ State History 4 American Legion 5 Boys’ Nation 5 Nevada Boys’ State Governors 5 Nevada Boys’ State Alumni Association 5 Staff 6 Nevada Boys’ State Hall of Fame 6 The Future of Nevada Boys’ State 6 PROGRAM PREPARATION ........................................................... 7 What to Bring 7 Legislation Submission 8 NEVADA BOYS’ STATE STRUCTURE ......................................... 9 Rules Pertaining to Political Office 9 Political Parties 9 Party Committees 10 Recommended Party Platform 12 The City 13 The State 14 The Judiciary: Moot Court 15 The Judiciary: Nevada Boys’ State Statutes 16 Elected Positions & Conflict Chart* 19 The Boys’ State Monetary System 21 LEGISLATIVE PROCESS ............................................................... 22 Introduction 22 Bills 22 Submitting and Writing a Bill Online 24 Committees 25 Standing Rules and Procedures of the Senate and Assembly 26 How a Bill Becomes a Law: Graphical Representation 27 The Ten Principles 28 Types of Motions 28 Five Steps to Every Motion 28 Methods of Voting on a Motion 29 Table of Motions 30 PROGRAM THEME ........................................................................ 31 What is Leadership? 31 United States Flag Code 32 DAILY HONORS ............................................................................. 33 Boys’ State Creed 33 Resolution 288 33 Songs 33 CODE OF CONDUCT .................................................................... -

Delaying Judgment

Volume 26 Number 3, March 2012 MERGERS AND AQUISITIONS Delaying Judgment Day: How an adjournment, the meeting is convened without taking a stockholder vote, but then reconvened to Defer Stockholder Votes in at a later time and date. However, a stockholder Contested M&A Transactions meeting also can be postponed or recessed. In a postponement, the previously scheduled stock- holder meeting is not convened, but is delayed to In connection with an M&A transaction, pub- a subsequent time and date. In a recess, the stock- lic companies sometimes fi nd it desirable to delay holder meeting is convened, and then “recessed” a previously scheduled stockholders meeting. without taking a stockholder vote and continued Adjournment is the most traditional method, but at a later time and date. a recess or postponement may be appropriate. In any event, a review of the company’s charter and The determination of whether a company can bylaws, applicable state or foreign law, the federal delay its previously scheduled stockholder vote, securities laws and the agreements governing the and the best method of doing so, requires a rigor- transaction must be analyzed. ous analysis of the company’s charter and bylaws, applicable state or foreign law, the federal securi- by Lois Herzeca and Eduardo Gallardo ties laws, and the agreements governing the trans- action. Public companies that are seeking stockholder approval of a contested business combination Reviewing Organizational Documents transaction have sometimes found it desirable to delay a previously scheduled meeting of stock- As an initial matter, both the charter and holders. The company may wish to provide stock- bylaws of the company should be reviewed to holders with additional time to consider new determine if, and to the extent that, they address information (such as a new or revised acquisition the ability of the board of directors, or the chair proposal), may need additional time to solicit of the meeting, to delay a stockholders meeting.