The Artistic Self-Image of Artemisia Gentileschi by Kevin Rojas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elisabetta Sirani Dipinti Devozionali E “Quadretti Da Letto” Di Una Virtuosa Del Pennello

Temporary exhibition from the storage. LISABETTA E IRANI DipintiS devozionali e “quadretti da letto” di una virtuosa del pennello Palazzo Pepoli Campogrande 18 september - 25 november 2018 Elisabetta Sirani Dipinti devozionali e “quadretti da letto” di una virtuosa del pennello The concept of the exhibition is linked to an important recovery realized by the Nucleo Carabinieri Tutela Patrimonio Culturale of Bologna: the finding on the antique market, thanks to the advisory of the Pinacoteca, of a small painting with a Virgin praying attributed to the well-known Bolognese painter Elisabetta Sirani (Bologna 1638-1665), whose disappearance has been denounced by Enrico Mauceri in 1930. The restitution of the work to the Pinacoteca and its presentation to the public is accompanied by an exposition of some paintings of Elisabetta, usually kept into the museum storage, with the others normally showed in the gallery (Saint Anthony of Padua adoring Christ Child) and in Palazzo Pepoli Elisabetta Sirani, Virgin praying, Campogrande (Saint Mary Magdalene and Saint Jerome). canvas, cm 46x36, Inv. 625 The aim of this intimate exhibition is to ce- lebrate Elisabetta Sirani as one of the most representative personalities of the Bolognese School in the XVII century, who followed the artistic lesson of the divine Guido Reni. Actually, Elisabetta was not directly a student of Reni, who died when she was four years old. First of four kids, she learnt from her father Giovanni Andrea Sirani, who was direct student of Guido. We can imagine how much the collection of Reni’s drawings kept by Giovanni inspired our young painter, who started to practise in a short while. -

ELISABETTA SIRANI's JUDITH with the HEAD of HOLOFERNES By

ELISABETTA SIRANI’S JUDITH WITH THE HEAD OF HOLOFERNES by JESSICA COLE RUBINSKI (Under the Direction of Shelley Zuraw) ABSTRACT This thesis examines the life and artistic career of the female artist, Elisabetta Sirani. The paper focuses on her unparalleled depictions of heroines, especially her Judith with the Head of Holofernes. By tracing the iconography of Judith from masters of the Renaissance into the mid- seventeenth century, it is evident that Elisabetta’s painting from 1658 is unique as it portrays Judith in her ultimate triumph. Furthermore, an emphasis is placed on the relationship between Elisabetta’s Judith and three of Guido Reni’s Judith images in terms of their visual resemblances, as well as their symbolic similarities through the incorporation of a starry sky and crescent moon. INDEX WORDS: Elisabetta Sirani, Judith, Holofernes, heroines, Timoclea, Giovanni Andrea Sirani, Guido Reni, female artists, Italian Baroque, Bologna ELISABETTA SIRANI’S JUDITH WITH THE HEAD OF HOLOFERNES by JESSICA COLE RUBINSKI B.A., Florida State University, 2003 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2008 © 2008 Jessica Cole Rubinski All Rights Reserved ELISABETTA SIRANI’S JUDITH WITH THE HEAD OF HOLOFERNES by JESSICA COLE RUBINSKI Major Professor: Dr. Shelley Zuraw Committee: Dr. Isabelle Wallace Dr. Asen Kirin Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2008 iv To my Family especially To my Mother, Pamela v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to thank Robert Henson of Carolina Day School for introducing me to the study of Art History, and the professors at Florida State University for continuing to spark my interest and curiosity for the subject. -

The Symbolism of Blood in Two Masterpieces of the Early Italian Baroque Art

The Symbolism of blood in two masterpieces of the early Italian Baroque art Angelo Lo Conte Throughout history, blood has been associated with countless meanings, encompassing life and death, power and pride, love and hate, fear and sacrifice. In the early Baroque, thanks to the realistic mi of Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi, blood was transformed into a new medium, whose powerful symbolism demolished the conformed traditions of Mannerism, leading art into a new expressive era. Bearer of macabre premonitions, blood is the exclamation mark in two of the most outstanding masterpieces of the early Italian Seicento: Caravaggio's Beheading a/the Baptist (1608)' (fig. 1) and Artemisia Gentileschi's Judith beheading Halo/ernes (1611-12)2 (fig. 2), in which two emblematic events of the Christian tradition are interpreted as a representation of personal memories and fears, generating a powerful spiral of emotions which constantly swirls between fiction and reality. Through this paper I propose that both Caravaggio and Aliemisia adopted blood as a symbolic representation of their own life-stories, understanding it as a vehicle to express intense emotions of fear and revenge. Seen under this perspective, the red fluid results as a powerful and dramatic weapon used to shock the viewer and, at the same time, express an intimate and anguished condition of pain. This so-called Caravaggio, The Beheading of the Baptist, 1608, Co-Cathedral of Saint John, Oratory of Saint John, Valletta, Malta. 2 Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith beheading Halafernes, 1612-13, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples. llO Angelo La Conte 'terrible naturalism'3 symbolically demarks the transition from late Mannerism to early Baroque, introducing art to a new era in which emotions and illusion prevail on rigid and controlled representation. -

Elisabetta Sirani Dipinti Devozionali E “Quadretti Da Letto” Di Una Virtuosa Del Pennello

Elisabetta Sirani Dipinti devozionali e “quadretti da letto” di una virtuosa del pennello L’idea del percorso tra questi dipinti nasce a seguito di un importante recupero realizzato dal Nucleo Carabinieri Tutela Patrimonio Culturale di Bologna: il ritrovamento sul mercato antiquario, grazie a una segnalazione del Museo, di un piccolo dipinto raffigurante la Vergine orante attribuito alla celebre pittrice bolognese Elisabetta Sirani (Bologna 1638-1665), la cui scomparsa dalla Pinacoteca di Bologna era stata denunciata da Enrico Mauceri nel 1930. L’esposizione del dipinto ritrovato diventa occasione per presentare al pubblico altri lavori dell’artista generalmente conservati nei depositi, spazi da non considerarsi soltanto incubatori di oggetti, ma come una fonte di ricche testimonianze di un passato intangibile, spesso celato e sconosciuto al pubblico per motivi conservativi. Si ha così l’occasione di scoprire la personalità innovativa di una delle principali protagoniste della storia della pittura del Seicento. Elisabetta Sirani nasce a Bologna nel 1638 da Margherita e Giovanni Andrea Sirani, allievo e diretto collaboratore di Guido Reni. Studiò la tradizione classica del divino maestro nella bottega del padre, grazie al quale entrò in contatto con il mercato e la committenza cittadina, a cui affidò le sue opere più importanti. Elisabetta iniziò fin da subito la sua carriera da pittrice, aprendo già all’età di ventiquattro anni una bottega molto frequentata, nella quale spiccava la presenza di numerose donne. Nonostante la sua breve vita – infatti morì a soli ventisette anni – Elisabetta viene ricordata già dallo storico contemporaneo Carlo Cesare Malvasia per le sue doti pittoriche: definita “virtuosa” per la rapidità del segno e la maestria nell’arte della pittura, veniva addirittura ammirata dai passanti che si fermavano davanti la sua bottega. -

Light and Sight in Ter Brugghen's Man Writing by Candlelight

Volume 9, Issue 1 (Winter 2017) Light and Sight in ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight Susan Donahue Kuretsky [email protected] Recommended Citation: Susan Donahue Kuretsky, “Light and Sight in ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight,” JHNA 9:1 (Winter 2017) DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2017.9.1.4 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/light-sight-ter-brugghens-man-writing-by-candlelight/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 7:2 (Summer 2015) 1 LIGHT AND SIGHT IN TER BRUGGHEN’S MAN WRITING BY CANDLELIGHT Susan Donahue Kuretsky Ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight is commonly seen as a vanitas tronie of an old man with a flickering candle. Reconsideration of the figure’s age and activity raises another possibility, for the image’s pointed connection between light and sight and the fact that the figure has just signed the artist’s signature and is now completing the date suggests that ter Brugghen—like others who elevated the role of the artist in his period—was more interested in conveying the enduring aliveness of the artistic process and its outcome than in reminding the viewer about the transience of life. DOI:10.5092/jhna.2017.9.1.4 Fig. 1 Hendrick ter Brugghen, Man Writing by Candlelight, ca. -

ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI ARTEMISIA ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI E Il Suo Tempo

ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI e il suo tempo Attraverso un arco temporale che va dal 1593 al 1653, questo volume svela gli aspetti più autentici di Artemisia Gentileschi, pittrice di raro talento e straordinaria personalità artistica. Trenta opere autografe – tra cui magnifici capolavori come l’Autoritratto come suonatrice di liuto del Wadsworth Atheneum di Hartford, la Giuditta decapita Oloferne del Museo di Capodimonte e l’Ester e As- suero del Metropolitan Museum di New York – offrono un’indagine sulla sua carriera e sulla sua progressiva ascesa che la vide affermarsi a Firenze (dal 1613 al 1620), Roma (dal 1620 al 1626), Venezia (dalla fine del 1626 al 1630) e, infine, a Napoli, dove visse fino alla morte. Per capire il ruolo di Artemisia Gentileschi nel panorama del Seicento, le sue opere sono messe a confronto con quelle di altri grandi protagonisti della sua epoca, come Cristofano Allori, Simon Vouet, Giovanni Baglione, Antiveduto Gramatica e Jusepe de Ribera. e il suo tempo Skira € 38,00 Artemisia Gentileschi e il suo tempo Roma, Palazzo Braschi 30 novembre 2016 - 7 maggio 2017 In copertina Artemisia Gentileschi, Giuditta che decapita Oloferne, 1620-1621 circa Firenze, Gallerie degli Uffizi, inv. 1597 Virginia Raggi Direzione Musei, Presidente e Capo Ufficio Stampa Albino Ruberti (cat. 28) Sindaca Ville e Parchi storici Amministratore Adele Della Sala Amministratore Delegato Claudio Parisi Presicce, Iole Siena Luca Bergamo Ufficio Stampa Roberta Biglino Art Director Direttore Marcello Francone Assessore alla Crescita -

ARTS 5306 Crosslisted with 4306 Baroque Art History Fall 2020

ARTS 5306 crosslisted with 4306 Baroque Art HIstory fall 2020 Instructor: Jill Carrington [email protected] tel. 468-4351; Office 117 Office hours: MWF 11:00 - 11:30, MW 4:00 – 5:00; TR 11:00 – 12:00, 4:00 – 5:00 other times by appt. Class meets TR 2:00 – 3:15 in the Art History Room 106 in the Art Annex and remotely. Course description: European art from 1600 to 1750. Prerequisites: 6 hours in art including ART 1303 and 1304 (Art History I and II) or the equivalent in history. Text: Not required. The artists and most artworks come from Ann Sutherland Harris, Seventeenth Century Art and Architecture. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, Prentice Hall, 2e, 2008 or 1e, 2005. One copy of the 1e is on four-hour reserve in Steen Library. Used copies of the both 1e and 2e are available online; for I don’t require you to buy the book; however, you may want your own copy or share one. Objectives: .1a Broaden your interest in Baroque art in Europe by examining artworks by artists we studied in Art History II and artists perhaps new to you. .1b Understand the social, political and religious context of the art. .2 Identify major and typical works by leading artists, title and country of artist’s origin and terms (id quizzes). .3 Short essays on artists & works of art (midterm and end-term essay exams) .4 Evidence, analysis and argument: read an article and discuss the author’s thesis, main points and evidence with a small group of classmates. -

Download Download

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 09, Issue 06, 2020: 01-11 Article Received: 26-04-2020 Accepted: 05-06-2020 Available Online: 13-06-2020 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/journal.v9i6.1920 Caravaggio and Tenebrism—Beauty of light and shadow in baroque paintings Andy Xu1 ABSTRACT The following paper examines the reasons behind the use of tenebrism by Caravaggio under the special context of Counter-Reformation and its influence on later artists during the Baroque in Northern Europe. As Protestantism expanded throughout the entire Europe, the Catholic Church was seeking artistic methods to reattract believers. Being the precursor of Counter-Reformation art, Caravaggio incorporated tenebrism in his paintings. Art historians mostly correlate the use of tenebrism with religion, but there have also been scholars proposing how tenebrism reflects a unique naturalism that only belongs to Caravaggio. The paper will thus start with the introduction of tenebrism, discuss the two major uses of this artistic technique and will finally discuss Caravaggio’s legacy until today. Keywords: Caravaggio, Tenebrism, Counter-Reformation, Baroque, Painting, Religion. This is an open access article under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. 1. Introduction Most scholars agree that the Baroque range approximately from 1600 to 1750. There are mainly four aspects that led to the Baroque: scientific experimentation, free-market economies in Northern Europe, new philosophical and political ideas, and the division in the Catholic Church due to criticism of its corruption. Despite the fact that Galileo's discovery in astronomy, the Tulip bulb craze in Amsterdam, the diplomatic artworks by Peter Paul Rubens, the music by Johann Sebastian Bach, the Mercantilist economic theories of Colbert, the Absolutism in France are all fascinating, this paper will focus on the sophisticated and dramatic production of Catholic art during the Counter-Reformation ("Baroque Art and Architecture," n.d.). -

COVER NOVEMBER Prova.Qxd

52-54 Lucy Art March-Aprilcorr1_*FACE MANOPPELLO DEF.qxd 2/28/21 12:12 PM Page 52 OIfN B TooHksE, AErYt EaSn dO PFe oTpHle E BEHOLDERS n BY LUCY GORDAN (“The NIl eMwo nWdoor lNd”o)v bo y Giandomenico Tiepolo, from the Prado, Madrid. Below , bTyh eR eGmirlb irna na dt, fFroramm te he Royal Castle Museum, Warsaw affeo Barberini (1568-1644) became Pope Urban the help of Borromini, Bernini took over. The exterior, in - VIII on August 6, 1623. During his reign he ex - spired by the Colosseum and similar in appearance to the Mpanded papal territory by force of arms and advan - Palazzo Farnese, which had been constructed between 1541 tageous politicking and reformed church missions. But he and c. 1580, was completed in 1633. is certainly best remembered as a prominent patron of the When Urban VIII died, his successor Pamphili Pope In - arts on a grand scale. nocent X (r. 1644-1655) confiscated the Palazzo Barberini, Barberini funded many sculptures from Bernini: the but returned it in 1653. From then on it continued to remain first in c. 1617 the “Boy with a Dragon” and later, when the property of the Barberini family until 1949 when it was Pope, several portrait busts, but also numerous architectural bought by the Italian Government to become the art museum works including the building of the College of Propaganda it is today. But there was a problem: in 1934 the Barberinis Fide, the Fountain of the Triton in today’s Piazza Barberini, had rented a section of the building to the Army for its Offi - and the and the in St. -

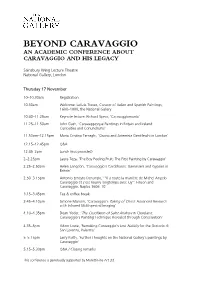

Programme for Beyond Caravaggio

BEYOND CARAVAGGIO AN ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ABOUT CARAVAGGIO AND HIS LEGACY Sainsbury Wing Lecture Theatre National Gallery, London Thursday 17 November 10–10.30am Registration 10.30am Welcome: Letizia Treves, Curator of Italian and Spanish Paintings, 1600–1800, the National Gallery 10.40–11.25am Keynote lecture: Richard Spear, ‘Caravaggiomania’ 11.25–11.50am John Gash, ‘Caravaggesque Paintings in Britain and Ireland: Curiosities and Conundrums’ 11.50am–12.15pm Maria Cristina Terzaghi, ‘Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi in London’ 12.15–12.45pm Q&A 12.45–2pm Lunch (not provided) 2–2.25pm Laura Teza, ‘The Boy Peeling Fruit: The First Painting by Caravaggio’ 2.25–2.50pm Helen Langdon, ‘Caravaggio's Cardsharps: Gamesters and Gypsies in Britain’ 2.50–3.15pm Antonio Ernesto Denunzio, ‘“Il a toute la manière de Michel Angelo Caravaggio et s'est nourry longtemps avec luy”: Finson and Caravaggio, Naples 1606–10’ 3.15–3.45pm Tea & coffee break 3.45–4.10pm Simone Mancini, ‘Caravaggio's Taking of Christ: Advanced Research with Infrared Multispectral Imaging’ 4.10–4.35pm Dean Yoder, ‘The Crucifixion of Saint Andrew in Cleveland: Caravaggio’s Painting Technique Revealed through Conservation’ 4.35–5pm Adam Lowe, ‘Remaking Caravaggio’s Lost Nativity for the Oratorio di San Lorenzo, Palermo’ 5–5.15pm Larry Keith, ‘Further Thoughts on the National Gallery’s paintings by Caravaggio’ 5.15–5.30pm Q&A / Closing remarks This conference is generously supported by Moretti Fine Art Ltd. BEYOND CARAVAGGIO AN ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ABOUT CARAVAGGIO AND HIS LEGACY Sainsbury -

The Consummate Etcher and Other 17Th Century Printmakers SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY

THE CONSUMMATE EtcHER and other 17TH Century Printmakers SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY ART GALLERIES THE CONSUMMATE EtcHER and other 17th Century Printmakers A Celebration of Louise and Bernard Palitz and their association with The Syracuse University Art Galleries curated by Domenic J. Iacono CONTENTS SEptEMBER 16- NOVEMBER 14, 2013 Louise and Bernard Palitz Gallery Acknowledgements . 2 Lubin House, Syracuse University Introduction . 4 New York City, New York Landscape Prints . 6 Genre Prints . 15 Portraits . 25 Religious Prints . 32 AcKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Syracuse University Art Galleries is proud to Mr. Palitz was a serious collector of fine arts and present Rembrandt: The Consummate Etcher and after attending a Museum Studies class as a other 17th century Printmakers. This exhibition guest, offered to help realize the class lectures primarily utilizes the holdings of the Syracuse as an exhibition. We immediately began making University Art Collection and explores the impact plans to show the exhibition at both our campus of one of Europe’s most important artists on the and New York City galleries. printmakers of his day. This project, which grew out of a series of lectures for the Museum Studies The generosity of Louise and Bernard Palitz Graduate class Curatorship and Connoisseurship also made it possible to collaborate with other of Prints, demonstrates the value of a study institutions such as Cornell University and the collection as a teaching tool that can extend Herbert Johnson Museum of Art, the Dahesh outside the classroom. Museum of Art, and the Casa Buonarroti in Florence on our exhibition programming. Other In the mid-1980s, Louise and Bernard Palitz programs at Syracuse also benefitted from their made their first gift to the Syracuse University generosity including the Public Agenda Policy Art Collection and over the next 25 years they Breakfasts that bring important political figures to became ardent supporters of Syracuse University New York City for one-on-one interviews as part and our arts programs. -

The Encounter of the Emblematic Tradition with Optics the Anamorphic Elephant of Simon Vouet

Nuncius 31 (2016) 288–331 brill.com/nun The Encounter of the Emblematic Tradition with Optics The Anamorphic Elephant of Simon Vouet Susana Gómez López* Faculty of Philosophy, Complutense University, Madrid, Spain [email protected] Abstract In his excellent work Anamorphoses ou perspectives curieuses (1955), Baltrusaitis con- cluded the chapter on catoptric anamorphosis with an allusion to the small engraving by Hans Tröschel (1585–1628) after Simon Vouet’s drawing Eight satyrs observing an ele- phantreflectedonacylinder, the first known representation of a cylindrical anamorpho- sis made in Europe. This paper explores the Baroque intellectual and artistic context in which Vouet made his drawing, attempting to answer two central sets of questions. Firstly, why did Vouet make this image? For what purpose did he ideate such a curi- ous image? Was it commissioned or did Vouet intend to offer it to someone? And if so, to whom? A reconstruction of this story leads me to conclude that the cylindrical anamorphosis was conceived as an emblem for Prince Maurice of Savoy. Secondly, how did what was originally the project for a sophisticated emblem give rise in Paris, after the return of Vouet from Italy in 1627, to the geometrical study of catoptrical anamor- phosis? Through the study of this case, I hope to show that in early modern science the emblematic tradition was not only linked to natural history, but that insofar as it was a central feature of Baroque culture, it seeped into other branches of scientific inquiry, in this case the development of catoptrical anamorphosis. Vouet’s image is also a good example of how the visual and artistic poetics of the baroque were closely linked – to the point of being inseparable – with the scientific developments of the period.