Atwood's Machine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atwood's Machine? (5 Points)

rev 09/2019 Atwood’s Machine Equipment Qty Equipment Part Number 1 Mass and Hanger Set ME‐8979 1 Photogate with Pully ME‐6838A 1 Universal Table Clamp ME‐9376B 1 Large Rod ME‐8736 1 Small Rod ME‐8977 1 Double rod Clamp ME‐9873 1 String Background Newton’s 2nd Law (NSL) states that the acceleration a mass experiences is proportional to the net force applied to it, and inversely proportional to its inertial mass ( ). An Atwood’s Machine is a simple device consisting of a pulley, with two masses connected by a string that runs over the pulley. For an ‘ideal Atwood’s Machine’ we assume the pulley is massless, and frictionless, that the string is unstretchable, therefore a constant length, and also massless. Consider the following diagram of an ideal Atwood’s machine. One of the standard ways to apply NSL is to draw Free Body Diagrams for the masses in the system, then write Force Summation Equations for each Free Body Diagram. We will use the standard practice of labeling masses from smallest to largest, therefore m2 > m1. For an Atwood’s Machine there are only forces acting on the masses in the vertical direction so we will only need to write Force Summation Equations for the y‐direction. We obtain the following Free Body Diagrams for the two masses. Each of the masses have two forces acting on it. Each has its own weight (m1g, or m2g) pointing downwards, and each has the tension (T) in the string pointing upwards. By the assumption of an ideal string the tension is the same throughout the string. -

Chapter 3 Motion in Two and Three Dimensions

Chapter 3 Motion in Two and Three Dimensions 3.1 The Important Stuff 3.1.1 Position In three dimensions, the location of a particle is specified by its location vector, r: r = xi + yj + zk (3.1) If during a time interval ∆t the position vector of the particle changes from r1 to r2, the displacement ∆r for that time interval is ∆r = r1 − r2 (3.2) = (x2 − x1)i +(y2 − y1)j +(z2 − z1)k (3.3) 3.1.2 Velocity If a particle moves through a displacement ∆r in a time interval ∆t then its average velocity for that interval is ∆r ∆x ∆y ∆z v = = i + j + k (3.4) ∆t ∆t ∆t ∆t As before, a more interesting quantity is the instantaneous velocity v, which is the limit of the average velocity when we shrink the time interval ∆t to zero. It is the time derivative of the position vector r: dr v = (3.5) dt d = (xi + yj + zk) (3.6) dt dx dy dz = i + j + k (3.7) dt dt dt can be written: v = vxi + vyj + vzk (3.8) 51 52 CHAPTER 3. MOTION IN TWO AND THREE DIMENSIONS where dx dy dz v = v = v = (3.9) x dt y dt z dt The instantaneous velocity v of a particle is always tangent to the path of the particle. 3.1.3 Acceleration If a particle’s velocity changes by ∆v in a time period ∆t, the average acceleration a for that period is ∆v ∆v ∆v ∆v a = = x i + y j + z k (3.10) ∆t ∆t ∆t ∆t but a much more interesting quantity is the result of shrinking the period ∆t to zero, which gives us the instantaneous acceleration, a. -

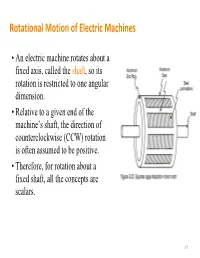

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines • An electric machine rotates about a fixed axis, called the shaft, so its rotation is restricted to one angular dimension. • Relative to a given end of the machine’s shaft, the direction of counterclockwise (CCW) rotation is often assumed to be positive. • Therefore, for rotation about a fixed shaft, all the concepts are scalars. 17 Angular Position, Velocity and Acceleration • Angular position – The angle at which an object is oriented, measured from some arbitrary reference point – Unit: rad or deg – Analogy of the linear concept • Angular acceleration =d/dt of distance along a line. – The rate of change in angular • Angular velocity =d/dt velocity with respect to time – The rate of change in angular – Unit: rad/s2 position with respect to time • and >0 if the rotation is CCW – Unit: rad/s or r/min (revolutions • >0 if the absolute angular per minute or rpm for short) velocity is increasing in the CCW – Analogy of the concept of direction or decreasing in the velocity on a straight line. CW direction 18 Moment of Inertia (or Inertia) • Inertia depends on the mass and shape of the object (unit: kgm2) • A complex shape can be broken up into 2 or more of simple shapes Definition Two useful formulas mL2 m J J() RRRR22 12 3 1212 m 22 JRR()12 2 19 Torque and Change in Speed • Torque is equal to the product of the force and the perpendicular distance between the axis of rotation and the point of application of the force. T=Fr (Nm) T=0 T T=Fr • Newton’s Law of Rotation: Describes the relationship between the total torque applied to an object and its resulting angular acceleration. -

6. Non-Inertial Frames

6. Non-Inertial Frames We stated, long ago, that inertial frames provide the setting for Newtonian mechanics. But what if you, one day, find yourself in a frame that is not inertial? For example, suppose that every 24 hours you happen to spin around an axis which is 2500 miles away. What would you feel? Or what if every year you spin around an axis 36 million miles away? Would that have any e↵ect on your everyday life? In this section we will discuss what Newton’s equations of motion look like in non- inertial frames. Just as there are many ways that an animal can be not a dog, so there are many ways in which a reference frame can be non-inertial. Here we will just consider one type: reference frames that rotate. We’ll start with some basic concepts. 6.1 Rotating Frames Let’s start with the inertial frame S drawn in the figure z=z with coordinate axes x, y and z.Ourgoalistounderstand the motion of particles as seen in a non-inertial frame S0, with axes x , y and z , which is rotating with respect to S. 0 0 0 y y We’ll denote the angle between the x-axis of S and the x0- axis of S as ✓.SinceS is rotating, we clearly have ✓ = ✓(t) x 0 0 θ and ✓˙ =0. 6 x Our first task is to find a way to describe the rotation of Figure 31: the axes. For this, we can use the angular velocity vector ! that we introduced in the last section to describe the motion of particles. -

Physics 114 Tutorial 5: Tension Instructor: Adnan Khan

• Please do not sit alone. Sit next to at least one student. • Please leave rows C, F, J, and M open. Physics 114 Tutorial 5: Tension Instructor: Adnan Khan 5/7/19 1 Blocks connected by a rope q Section 1: Two blocks, A and B, are tied together with a rope of mass M. Block B is being pushed with a constant horizontal force as shown at right. Assume that there is no friction between the blocks and the blocks are moving to the right. 1. Describe the motion of block A, block B, and the rope. 2. Compare the acceleration of block A, block B and the rope. 5/7/19 2 Blocks connected by a rope 2. Compare the accelerations of block A, block B and the rope. A. aA > aR > aB B. aB > aA > aR C. aA > aB > aR D. aB > aR > aA E. aA = aR = aB 5/7/19 3 Blocks connected by a rope 3. Draw a separate free-body diagram for each block and for the rope. Clearly label your forces. 5/7/19 4 Blocks connected by a rope 4. Rank, from largest to smallest, the magnitudes of the horizontal components of the forces on your diagrams. 5/7/19 5 Blocks connected by a very light string q Section 2: The blocks in section 1 are now connected with a very light, flexible, and inextensible string of mass m (m < M). Suppose the hand pushes so the acceleration of the blocks is the same as in section 1. Blocks have same acceleration as with rope 5. -

Rotation: Moment of Inertia and Torque

Rotation: Moment of Inertia and Torque Every time we push a door open or tighten a bolt using a wrench, we apply a force that results in a rotational motion about a fixed axis. Through experience we learn that where the force is applied and how the force is applied is just as important as how much force is applied when we want to make something rotate. This tutorial discusses the dynamics of an object rotating about a fixed axis and introduces the concepts of torque and moment of inertia. These concepts allows us to get a better understanding of why pushing a door towards its hinges is not very a very effective way to make it open, why using a longer wrench makes it easier to loosen a tight bolt, etc. This module begins by looking at the kinetic energy of rotation and by defining a quantity known as the moment of inertia which is the rotational analog of mass. Then it proceeds to discuss the quantity called torque which is the rotational analog of force and is the physical quantity that is required to changed an object's state of rotational motion. Moment of Inertia Kinetic Energy of Rotation Consider a rigid object rotating about a fixed axis at a certain angular velocity. Since every particle in the object is moving, every particle has kinetic energy. To find the total kinetic energy related to the rotation of the body, the sum of the kinetic energy of every particle due to the rotational motion is taken. The total kinetic energy can be expressed as .. -

Lecture 25 Torque

Physics 170 - Mechanics Lecture 25 Torque Torque From experience, we know that the same force will be much more effective at rotating an object such as a nut or a door if our hand is not too close to the axis. This is why we have long-handled wrenches, and why the doorknobs are not next to the hinges. Torque We define a quantity called torque: The torque increases as the force increases and also as the distance increases. Torque The ability of a force to cause a rotation or twisting motion depends on three factors: 1. The magnitude F of the force; 2. The distance r from the point of application to the pivot; 3. The angle φ at which the force is applied. = r x F Torque This leads to a more general definition of torque: Two Interpretations of Torque Torque Only the tangential component of force causes a torque: Sign of Torque If the torque causes a counterclockwise angular acceleration, it is positive; if it causes a clockwise angular acceleration, it is negative. Sign of Torque Question Five different forces are applied to the same rod, which pivots around the black dot. Which force produces the smallest torque about the pivot? (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) Gravitational Torque An object fixed on a pivot (taken as the origin) will experience gravitational forces that will produce torques. The torque about the pivot from the ith particle will be τi=−ximig. The minus sign is because particles to the right of the origin (x positive) will produce clockwise (negative) torques. -

Newton's First Law of Motion the Principle of Relativity

MATHEMATICS 7302 (Analytical Dynamics) YEAR 2017–2018, TERM 2 HANDOUT #1: NEWTON’S FIRST LAW AND THE PRINCIPLE OF RELATIVITY Newton’s First Law of Motion Our experience seems to teach us that the “natural” state of all objects is at rest (i.e. zero velocity), and that objects move (i.e. have a nonzero velocity) only when forces are being exerted on them. Aristotle (384 BCE – 322 BCE) thought so, and many (but not all) philosophers and scientists agreed with him for nearly two thousand years. It was Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) who first realized, through a combination of experi- mentation and theoretical reflection, that our everyday belief is utterly wrong: it is an illusion caused by the fact that we live in a world dominated by friction. By using lubricants to re- duce friction to smaller and smaller values, Galileo showed experimentally that objects tend to maintain nearly their initial velocity — whatever that velocity may be — for longer and longer times. He then guessed that, in the idealized situation in which friction is completely eliminated, an object would move forever at whatever velocity it initially had. Thus, an object initially at rest would stay at rest, but an object initially moving at 100 m/s east (for example) would continue moving forever at 100 m/s east. In other words, Galileo guessed: An isolated object (i.e. one subject to no forces from other objects) moves at constant velocity, i.e. in a straight line at constant speed. Any constant velocity is as good as any other. This principle was later incorporated in the physical theory of Isaac Newton (1642–1727); it is nowadays known as Newton’s first law of motion. -

Vibration Suppression in Simple Tension-Aligned Structures

VIBRATION SUPPRESSION IN SIMPLE TENSION-ALIGNED STRUCTURES By Tingli Cai A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Mechanical Engineering – Doctor of Philosophy 2016 ABSTRACT VIBRATION SUPPRESSION IN SIMPLE TENSION-ALIGNED STRUCTURES By Tingli Cai Tension-aligned structures have been proposed for space-based antenna applications that require high degree of accuracy. This type of structures use compression members to impart tension on the antenna, thus helping to maintain the shape and facilitate disturbance rejection. These struc- tures can be very large and therefore sensitive to low-frequency excitations. In this study, two control strategies are proposed for the purpose of vibration suppression. First, a semi-active con- trol strategy for tension-aligned structures is proposed, based on the concept of stiffness variation by sequential application and removal of constraints. The process funnels vibration energy from low-frequency to high-frequency modes of the structure, where it is dissipated naturally due to internal damping. In this strategy, two methods of stiffness variation were investigated, including: 1) variable stiffness hinges in the panels and 2) variable stiffness elastic bars connecting the panels to the support structure. Two-dimensional and three-dimensional models were built to demon- strate the effectiveness of the control strategy. The second control strategy proposed is an active scheme which uses sensor feedback to do negative work on the system and to suppress vibration. In particular, it employs a sliding mechanism where the constraint force is measured in real time and this information is used as feedback to prescribe the motion of the slider in such a way that the vibration energy is reduced from the structure continuously and directly. -

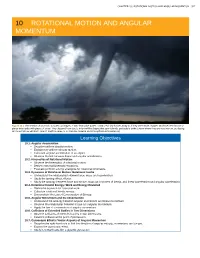

Rotational Motion and Angular Momentum 317

CHAPTER 10 | ROTATIONAL MOTION AND ANGULAR MOMENTUM 317 10 ROTATIONAL MOTION AND ANGULAR MOMENTUM Figure 10.1 The mention of a tornado conjures up images of raw destructive power. Tornadoes blow houses away as if they were made of paper and have been known to pierce tree trunks with pieces of straw. They descend from clouds in funnel-like shapes that spin violently, particularly at the bottom where they are most narrow, producing winds as high as 500 km/h. (credit: Daphne Zaras, U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) Learning Objectives 10.1. Angular Acceleration • Describe uniform circular motion. • Explain non-uniform circular motion. • Calculate angular acceleration of an object. • Observe the link between linear and angular acceleration. 10.2. Kinematics of Rotational Motion • Observe the kinematics of rotational motion. • Derive rotational kinematic equations. • Evaluate problem solving strategies for rotational kinematics. 10.3. Dynamics of Rotational Motion: Rotational Inertia • Understand the relationship between force, mass and acceleration. • Study the turning effect of force. • Study the analogy between force and torque, mass and moment of inertia, and linear acceleration and angular acceleration. 10.4. Rotational Kinetic Energy: Work and Energy Revisited • Derive the equation for rotational work. • Calculate rotational kinetic energy. • Demonstrate the Law of Conservation of Energy. 10.5. Angular Momentum and Its Conservation • Understand the analogy between angular momentum and linear momentum. • Observe the relationship between torque and angular momentum. • Apply the law of conservation of angular momentum. 10.6. Collisions of Extended Bodies in Two Dimensions • Observe collisions of extended bodies in two dimensions. • Examine collision at the point of percussion. -

Glossary of Materials Engineering Terminology

Glossary of Materials Engineering Terminology Adapted from: Callister, W. D.; Rethwisch, D. G. Materials Science and Engineering: An Introduction, 8th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, 2010. McCrum, N. G.; Buckley, C. P.; Bucknall, C. B. Principles of Polymer Engineering, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 1997. Brittle fracture: fracture that occurs by rapid crack formation and propagation through the material, without any appreciable deformation prior to failure. Crazing: a common response of plastics to an applied load, typically involving the formation of an opaque banded region within transparent plastic; at the microscale, the craze region is a collection of nanoscale, stress-induced voids and load-bearing fibrils within the material’s structure; craze regions commonly occur at or near a propagating crack in the material. Ductile fracture: a mode of material failure that is accompanied by extensive permanent deformation of the material. Ductility: a measure of a material’s ability to undergo appreciable permanent deformation before fracture; ductile materials (including many metals and plastics) typically display a greater amount of strain or total elongation before fracture compared to non-ductile materials (such as most ceramics). Elastic modulus: a measure of a material’s stiffness; quantified as a ratio of stress to strain prior to the yield point and reported in units of Pascals (Pa); for a material deformed in tension, this is referred to as a Young’s modulus. Engineering strain: the change in gauge length of a specimen in the direction of the applied load divided by its original gauge length; strain is typically unit-less and frequently reported as a percentage. -

Vectors and Coordinate Systems

Vectors and Coordinate Systems In Newtonian mechanics, we want to understand how material bodies interact with each other and how this affects their motion through space. In order to be able to make quantitative statements about this, we need a mathematical language for describing motion, which is known as kinematics. Part of the language of kinematics involves calculus, since we know that calculus lets us talk about how things change in a quantitative way. The other part of this mathematical language involves the notion of a vector, and the related concept of a coordinate system. Today we'll review the basic concepts of vectors and coordinate systems that we'll need, and then we'll add ideas from calculus in order to form the subject of kinematics. The starting point for describing the location of objects in space is to pick an arbitrary location, known as the origin, and to describe every other position in space by the displacement vector between the origin and that point. This is shown in Figure 1 Because vectors allow us to talk about lengths and orientations in a quantitative way, they are a natural tool for describing motion. Much in the same way that I might say my house is 1.3 miles Northwest of campus, I can say that the location of some particle is a certain distance from the origin, at some angle. We won't belabour all of the basic properties of vectors (such as addition and subtraction), but if you are rusty on these subjects, now is the time to review! Figure 1: A point in space being indicated by its displacement vector from the origin.