Speed & Acceleration Lesson Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Motion Projectile Motion,And Straight Linemotion, Differences Between the Similaritiesand 2 CHAPTER 2 Acceleration Make Thefollowing As Youreadthe ●

026_039_Ch02_RE_896315.qxd 3/23/10 5:08 PM Page 36 User-040 113:GO00492:GPS_Reading_Essentials_SE%0:XXXXXXXXXXXXX_SE:Application_File chapter 2 Motion section ●3 Acceleration What You’ll Learn Before You Read ■ how acceleration, time, and velocity are related Describe what happens to the speed of a bicycle as it goes ■ the different ways an uphill and downhill. object can accelerate ■ how to calculate acceleration ■ the similarities and differences between straight line motion, projectile motion, and circular motion Read to Learn Study Coach Outlining As you read the Velocity and Acceleration section, make an outline of the important information in A car sitting at a stoplight is not moving. When the light each paragraph. turns green, the driver presses the gas pedal and the car starts moving. The car moves faster and faster. Speed is the rate of change of position. Acceleration is the rate of change of velocity. When the velocity of an object changes, the object is accelerating. Remember that velocity is a measure that includes both speed and direction. Because of this, a change in velocity can be either a change in how fast something is moving or a change in the direction it is moving. Acceleration means that an object changes it speed, its direction, or both. How are speeding up and slowing down described? ●D Construct a Venn When you think of something accelerating, you probably Diagram Make the following trifold Foldable to compare and think of it as speeding up. But an object that is slowing down contrast the characteristics of is also accelerating. Remember that acceleration is a change in acceleration, speed, and velocity. -

Frames of Reference

Galilean Relativity 1 m/s 3 m/s Q. What is the women velocity? A. With respect to whom? Frames of Reference: A frame of reference is a set of coordinates (for example x, y & z axes) with respect to whom any physical quantity can be determined. Inertial Frames of Reference: - The inertia of a body is the resistance of changing its state of motion. - Uniformly moving reference frames (e.g. those considered at 'rest' or moving with constant velocity in a straight line) are called inertial reference frames. - Special relativity deals only with physics viewed from inertial reference frames. - If we can neglect the effect of the earth’s rotations, a frame of reference fixed in the earth is an inertial reference frame. Galilean Coordinate Transformations: For simplicity: - Let coordinates in both references equal at (t = 0 ). - Use Cartesian coordinate systems. t1 = t2 = 0 t1 = t2 At ( t1 = t2 ) Galilean Coordinate Transformations are: x2= x 1 − vt 1 x1= x 2+ vt 2 or y2= y 1 y1= y 2 z2= z 1 z1= z 2 Recall v is constant, differentiation of above equations gives Galilean velocity Transformations: dx dx dx dx 2 =1 − v 1 =2 − v dt 2 dt 1 dt 1 dt 2 dy dy dy dy 2 = 1 1 = 2 dt dt dt dt 2 1 1 2 dz dz dz dz 2 = 1 1 = 2 and dt2 dt 1 dt 1 dt 2 or v x1= v x 2 + v v x2 =v x1 − v and Similarly, Galilean acceleration Transformations: a2= a 1 Physics before Relativity Classical physics was developed between about 1650 and 1900 based on: * Idealized mechanical models that can be subjected to mathematical analysis and tested against observation. -

Chapter 3 Motion in Two and Three Dimensions

Chapter 3 Motion in Two and Three Dimensions 3.1 The Important Stuff 3.1.1 Position In three dimensions, the location of a particle is specified by its location vector, r: r = xi + yj + zk (3.1) If during a time interval ∆t the position vector of the particle changes from r1 to r2, the displacement ∆r for that time interval is ∆r = r1 − r2 (3.2) = (x2 − x1)i +(y2 − y1)j +(z2 − z1)k (3.3) 3.1.2 Velocity If a particle moves through a displacement ∆r in a time interval ∆t then its average velocity for that interval is ∆r ∆x ∆y ∆z v = = i + j + k (3.4) ∆t ∆t ∆t ∆t As before, a more interesting quantity is the instantaneous velocity v, which is the limit of the average velocity when we shrink the time interval ∆t to zero. It is the time derivative of the position vector r: dr v = (3.5) dt d = (xi + yj + zk) (3.6) dt dx dy dz = i + j + k (3.7) dt dt dt can be written: v = vxi + vyj + vzk (3.8) 51 52 CHAPTER 3. MOTION IN TWO AND THREE DIMENSIONS where dx dy dz v = v = v = (3.9) x dt y dt z dt The instantaneous velocity v of a particle is always tangent to the path of the particle. 3.1.3 Acceleration If a particle’s velocity changes by ∆v in a time period ∆t, the average acceleration a for that period is ∆v ∆v ∆v ∆v a = = x i + y j + z k (3.10) ∆t ∆t ∆t ∆t but a much more interesting quantity is the result of shrinking the period ∆t to zero, which gives us the instantaneous acceleration, a. -

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines • An electric machine rotates about a fixed axis, called the shaft, so its rotation is restricted to one angular dimension. • Relative to a given end of the machine’s shaft, the direction of counterclockwise (CCW) rotation is often assumed to be positive. • Therefore, for rotation about a fixed shaft, all the concepts are scalars. 17 Angular Position, Velocity and Acceleration • Angular position – The angle at which an object is oriented, measured from some arbitrary reference point – Unit: rad or deg – Analogy of the linear concept • Angular acceleration =d/dt of distance along a line. – The rate of change in angular • Angular velocity =d/dt velocity with respect to time – The rate of change in angular – Unit: rad/s2 position with respect to time • and >0 if the rotation is CCW – Unit: rad/s or r/min (revolutions • >0 if the absolute angular per minute or rpm for short) velocity is increasing in the CCW – Analogy of the concept of direction or decreasing in the velocity on a straight line. CW direction 18 Moment of Inertia (or Inertia) • Inertia depends on the mass and shape of the object (unit: kgm2) • A complex shape can be broken up into 2 or more of simple shapes Definition Two useful formulas mL2 m J J() RRRR22 12 3 1212 m 22 JRR()12 2 19 Torque and Change in Speed • Torque is equal to the product of the force and the perpendicular distance between the axis of rotation and the point of application of the force. T=Fr (Nm) T=0 T T=Fr • Newton’s Law of Rotation: Describes the relationship between the total torque applied to an object and its resulting angular acceleration. -

Exploring Robotics Joel Kammet Supplemental Notes on Gear Ratios

CORC 3303 – Exploring Robotics Joel Kammet Supplemental notes on gear ratios, torque and speed Vocabulary SI (Système International d'Unités) – the metric system force torque axis moment arm acceleration gear ratio newton – Si unit of force meter – SI unit of distance newton-meter – SI unit of torque Torque Torque is a measure of the tendency of a force to rotate an object about some axis. A torque is meaningful only in relation to a particular axis, so we speak of the torque about the motor shaft, the torque about the axle, and so on. In order to produce torque, the force must act at some distance from the axis or pivot point. For example, a force applied at the end of a wrench handle to turn a nut around a screw located in the jaw at the other end of the wrench produces a torque about the screw. Similarly, a force applied at the circumference of a gear attached to an axle produces a torque about the axle. The perpendicular distance d from the line of force to the axis is called the moment arm. In the following diagram, the circle represents a gear of radius d. The dot in the center represents the axle (A). A force F is applied at the edge of the gear, tangentially. F d A Diagram 1 In this example, the radius of the gear is the moment arm. The force is acting along a tangent to the gear, so it is perpendicular to the radius. The amount of torque at A about the gear axle is defined as = F×d 1 We use the Greek letter Tau ( ) to represent torque. -

6. Non-Inertial Frames

6. Non-Inertial Frames We stated, long ago, that inertial frames provide the setting for Newtonian mechanics. But what if you, one day, find yourself in a frame that is not inertial? For example, suppose that every 24 hours you happen to spin around an axis which is 2500 miles away. What would you feel? Or what if every year you spin around an axis 36 million miles away? Would that have any e↵ect on your everyday life? In this section we will discuss what Newton’s equations of motion look like in non- inertial frames. Just as there are many ways that an animal can be not a dog, so there are many ways in which a reference frame can be non-inertial. Here we will just consider one type: reference frames that rotate. We’ll start with some basic concepts. 6.1 Rotating Frames Let’s start with the inertial frame S drawn in the figure z=z with coordinate axes x, y and z.Ourgoalistounderstand the motion of particles as seen in a non-inertial frame S0, with axes x , y and z , which is rotating with respect to S. 0 0 0 y y We’ll denote the angle between the x-axis of S and the x0- axis of S as ✓.SinceS is rotating, we clearly have ✓ = ✓(t) x 0 0 θ and ✓˙ =0. 6 x Our first task is to find a way to describe the rotation of Figure 31: the axes. For this, we can use the angular velocity vector ! that we introduced in the last section to describe the motion of particles. -

Rotation: Moment of Inertia and Torque

Rotation: Moment of Inertia and Torque Every time we push a door open or tighten a bolt using a wrench, we apply a force that results in a rotational motion about a fixed axis. Through experience we learn that where the force is applied and how the force is applied is just as important as how much force is applied when we want to make something rotate. This tutorial discusses the dynamics of an object rotating about a fixed axis and introduces the concepts of torque and moment of inertia. These concepts allows us to get a better understanding of why pushing a door towards its hinges is not very a very effective way to make it open, why using a longer wrench makes it easier to loosen a tight bolt, etc. This module begins by looking at the kinetic energy of rotation and by defining a quantity known as the moment of inertia which is the rotational analog of mass. Then it proceeds to discuss the quantity called torque which is the rotational analog of force and is the physical quantity that is required to changed an object's state of rotational motion. Moment of Inertia Kinetic Energy of Rotation Consider a rigid object rotating about a fixed axis at a certain angular velocity. Since every particle in the object is moving, every particle has kinetic energy. To find the total kinetic energy related to the rotation of the body, the sum of the kinetic energy of every particle due to the rotational motion is taken. The total kinetic energy can be expressed as .. -

Lecture 25 Torque

Physics 170 - Mechanics Lecture 25 Torque Torque From experience, we know that the same force will be much more effective at rotating an object such as a nut or a door if our hand is not too close to the axis. This is why we have long-handled wrenches, and why the doorknobs are not next to the hinges. Torque We define a quantity called torque: The torque increases as the force increases and also as the distance increases. Torque The ability of a force to cause a rotation or twisting motion depends on three factors: 1. The magnitude F of the force; 2. The distance r from the point of application to the pivot; 3. The angle φ at which the force is applied. = r x F Torque This leads to a more general definition of torque: Two Interpretations of Torque Torque Only the tangential component of force causes a torque: Sign of Torque If the torque causes a counterclockwise angular acceleration, it is positive; if it causes a clockwise angular acceleration, it is negative. Sign of Torque Question Five different forces are applied to the same rod, which pivots around the black dot. Which force produces the smallest torque about the pivot? (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) Gravitational Torque An object fixed on a pivot (taken as the origin) will experience gravitational forces that will produce torques. The torque about the pivot from the ith particle will be τi=−ximig. The minus sign is because particles to the right of the origin (x positive) will produce clockwise (negative) torques. -

Newton's First Law of Motion the Principle of Relativity

MATHEMATICS 7302 (Analytical Dynamics) YEAR 2017–2018, TERM 2 HANDOUT #1: NEWTON’S FIRST LAW AND THE PRINCIPLE OF RELATIVITY Newton’s First Law of Motion Our experience seems to teach us that the “natural” state of all objects is at rest (i.e. zero velocity), and that objects move (i.e. have a nonzero velocity) only when forces are being exerted on them. Aristotle (384 BCE – 322 BCE) thought so, and many (but not all) philosophers and scientists agreed with him for nearly two thousand years. It was Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) who first realized, through a combination of experi- mentation and theoretical reflection, that our everyday belief is utterly wrong: it is an illusion caused by the fact that we live in a world dominated by friction. By using lubricants to re- duce friction to smaller and smaller values, Galileo showed experimentally that objects tend to maintain nearly their initial velocity — whatever that velocity may be — for longer and longer times. He then guessed that, in the idealized situation in which friction is completely eliminated, an object would move forever at whatever velocity it initially had. Thus, an object initially at rest would stay at rest, but an object initially moving at 100 m/s east (for example) would continue moving forever at 100 m/s east. In other words, Galileo guessed: An isolated object (i.e. one subject to no forces from other objects) moves at constant velocity, i.e. in a straight line at constant speed. Any constant velocity is as good as any other. This principle was later incorporated in the physical theory of Isaac Newton (1642–1727); it is nowadays known as Newton’s first law of motion. -

Circular Motion Angular Velocity

PHY131H1F - Class 8 Quiz time… – Angular Notation: it’s all Today, finishing off Chapter 4: Greek to me! d • Circular Motion dt • Rotation θ is an angle, and the S.I. unit of angle is rad. The time derivative of θ is ω. What are the S.I. units of ω ? A. m/s2 B. rad / s C. N/m D. rad E. rad /s2 Last day I asked at the end of class: Quiz time… – Angular Notation: it’s all • You are driving North Highway Greek to me! d 427, on the smoothly curving part that will join to the Westbound 401. v dt Your speedometer is constant at 115 km/hr. Your steering wheel is The time derivative of ω is α. not rotating, but it is turned to the a What are the S.I. units of α ? left to follow the curve of the A. m/s2 highway. Are you accelerating? B. rad / s • ANSWER: YES! Any change in velocity, either C. N/m magnitude or speed, implies you are accelerating. D. rad • If so, in what direction? E. rad /s2 • ANSWER: West. If your speed is constant, acceleration is always perpendicular to the velocity, toward the centre of circular path. Circular Motion r = constant Angular Velocity s and θ both change as the particle moves s = “arc length” θ = “angular position” when θ is measured in radians when ω is measured in rad/s 1 Special case of circular motion: Uniform Circular Motion A carnival has a Ferris wheel where some seats are located halfway between the center Tangential velocity is and the outside rim. -

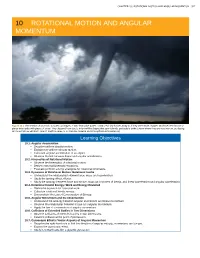

Rotational Motion and Angular Momentum 317

CHAPTER 10 | ROTATIONAL MOTION AND ANGULAR MOMENTUM 317 10 ROTATIONAL MOTION AND ANGULAR MOMENTUM Figure 10.1 The mention of a tornado conjures up images of raw destructive power. Tornadoes blow houses away as if they were made of paper and have been known to pierce tree trunks with pieces of straw. They descend from clouds in funnel-like shapes that spin violently, particularly at the bottom where they are most narrow, producing winds as high as 500 km/h. (credit: Daphne Zaras, U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) Learning Objectives 10.1. Angular Acceleration • Describe uniform circular motion. • Explain non-uniform circular motion. • Calculate angular acceleration of an object. • Observe the link between linear and angular acceleration. 10.2. Kinematics of Rotational Motion • Observe the kinematics of rotational motion. • Derive rotational kinematic equations. • Evaluate problem solving strategies for rotational kinematics. 10.3. Dynamics of Rotational Motion: Rotational Inertia • Understand the relationship between force, mass and acceleration. • Study the turning effect of force. • Study the analogy between force and torque, mass and moment of inertia, and linear acceleration and angular acceleration. 10.4. Rotational Kinetic Energy: Work and Energy Revisited • Derive the equation for rotational work. • Calculate rotational kinetic energy. • Demonstrate the Law of Conservation of Energy. 10.5. Angular Momentum and Its Conservation • Understand the analogy between angular momentum and linear momentum. • Observe the relationship between torque and angular momentum. • Apply the law of conservation of angular momentum. 10.6. Collisions of Extended Bodies in Two Dimensions • Observe collisions of extended bodies in two dimensions. • Examine collision at the point of percussion. -

Torque Speed Characteristics of a Blower Load

Torque Speed Characteristics of a Blower Load 1 Introduction The speed dynamics of a motor is given by the following equation dω J = T (ω) − T (ω) dt e L The performance of the motor is thus dependent on the torque speed characteristics of the motor and the load. The steady state operating speed (ωe) is determined by the solution of the equation Tm(ωe) = Te(ωe) Most of the loads can be classified into the following 4 general categories. 1.1 Constant torque type load A constant torque load implies that the torque required to keep the load running is the same at all speeds. A good example is a drum-type hoist, where the torque required varies with the load on the hook, but not with the speed of hoisting. Figure 1: Connection diagram 1.2 Torque proportional to speed The characteristics of the charge imply that the torque required increases with the speed. This par- ticularly applies to helical positive displacement pumps where the torque increases linearly with the speed. 1 Figure 2: Connection diagram 1.3 Torque proportional to square of the speed (fan type load) Quadratic torque is the most common load type. Typical applications are centrifugal pumps and fans. The torque is quadratically, and the power is cubically proportional to the speed. Figure 3: Connection diagram 1.4 Torque inversely proportional to speed (const power type load) A constant power load is normal when material is being rolled and the diameter changes during rolling. The power is constant and the torque is inversely proportional to the speed.