15. Parallel Axis Theorem and Torque A) Overview B) Parallel Axis Theorem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Experimental Determination of the Moment of Inertia of a Model Airplane Michael Koken [email protected]

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Honors Research Projects College Fall 2017 The Experimental Determination of the Moment of Inertia of a Model Airplane Michael Koken [email protected] Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the Aerospace Engineering Commons, Aviation Commons, Civil and Environmental Engineering Commons, Mechanical Engineering Commons, and the Physics Commons Recommended Citation Koken, Michael, "The Experimental Determination of the Moment of Inertia of a Model Airplane" (2017). Honors Research Projects. 585. http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/585 This Honors Research Project is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 2017 THE EXPERIMENTAL DETERMINATION OF A MODEL AIRPLANE KOKEN, MICHAEL THE UNIVERSITY OF AKRON Honors Project TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................ -

Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Robert Katz Publications Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy 1-1958 Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) Henry Semat City College of New York Robert Katz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz Part of the Physics Commons Semat, Henry and Katz, Robert, "Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)" (1958). Robert Katz Publications. 141. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz/141 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Katz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 11 Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) 11-1 Motion about a Fixed Axis The motion of the flywheel of an engine and of a pulley on its axle are examples of an important type of motion of a rigid body, that of the motion of rotation about a fixed axis. Consider the motion of a uniform disk rotat ing about a fixed axis passing through its center of gravity C perpendicular to the face of the disk, as shown in Figure 11-1. The motion of this disk may be de scribed in terms of the motions of each of its individual particles, but a better way to describe the motion is in terms of the angle through which the disk rotates. -

Velocity-Corrected Area Calculation SCIEX PA 800 Plus Empower

Velocity-corrected area calculation: SCIEX PA 800 Plus Empower Driver version 1.3 vs. 32 Karat™ Software Firdous Farooqui1, Peter Holper1, Steve Questa1, John D. Walsh2, Handy Yowanto1 1SCIEX, Brea, CA 2Waters Corporation, Milford, MA Since the introduction of commercial capillary electrophoresis (CE) systems over 30 years ago, it has been important to not always use conventional “chromatography thinking” when using CE. This is especially true when processing data, as there are some key differences between electrophoretic and chromatographic data. For instance, in most capillary electrophoresis separations, peak area is not only a function of sample load, but also of an analyte’s velocity past the detection window. In this case, early migrating peaks move past the detection window faster than later migrating peaks. This creates a peak area bias, as any relative difference in an analyte’s migration velocity will lead to an error in peak area determination and relative peak area percent. To help minimize Figure 1: The PA 800 Plus Pharmaceutical Analysis System. this bias, peak areas are normalized by migration velocity. The resulting parameter is commonly referred to as corrected peak The capillary temperature was maintained at 25°C in all area or velocity corrected area. separations. The voltage was applied using reverse polarity. This technical note provides a comparison of velocity corrected The following methods were used with the SCIEX PA 800 Plus area calculations using 32 Karat™ and Empower software. For Empower™ Driver v1.3: both, standard processing methods without manual integration were used to process each result. For 32 Karat™ software, IgG_HR_Conditioning: conditions the capillary Caesar integration1 was turned off. -

The Stress Tensor

An Internet Book on Fluid Dynamics The Stress Tensor The general state of stress in any homogeneous continuum, whether fluid or solid, consists of a stress acting perpendicular to any plane and two orthogonal shear stresses acting tangential to that plane. Thus, Figure 1: Differential element indicating the nine stresses. as depicted in Figure 1, there will be a similar set of three stresses acting on each of the three perpendicular planes in a three-dimensional continuum for a total of nine stresses which are most conveniently denoted by the stress tensor, σij, defined as the stress in the j direction acting on a plane normal to the i direction. Equivalently we can think of σij as the 3 × 3 matrix ⎡ ⎤ σxx σxy σxz ⎣ ⎦ σyx σyy σyz (Bha1) σzx σzy σzz in which the diagonal terms, σxx, σyy and σzz, are the normal stresses which would be equal to −p in any fluid at rest (note the change in the sign convention in which tensile normal stresses are positive whereas a positive pressure is compressive). The off-digonal terms, σij with i = j, are all shear stresses which would, of course, be zero in a fluid at rest and are proportional to the viscosity in a fluid in motion. In fact, instead of nine independent stresses there are only six because, as we shall see, the stress tensor is symmetric, specifically σij = σji. In other words the shear stress acting in the i direction on a face perpendicular to the j direction is equal to the shear stress acting in the j direction on a face perpendicular to the i direction. -

The Origins of Velocity Functions

The Origins of Velocity Functions Thomas M. Humphrey ike any practical, policy-oriented discipline, monetary economics em- ploys useful concepts long after their prototypes and originators are L forgotten. A case in point is the notion of a velocity function relating money’s rate of turnover to its independent determining variables. Most economists recognize Milton Friedman’s influential 1956 version of the function. Written v = Y/M = v(rb, re,1/PdP/dt, w, Y/P, u), it expresses in- come velocity as a function of bond interest rates, equity yields, expected inflation, wealth, real income, and a catch-all taste-and-technology variable that captures the impact of a myriad of influences on velocity, including degree of monetization, spread of banking, proliferation of money substitutes, devel- opment of cash management practices, confidence in the future stability of the economy and the like. Many also are aware of Irving Fisher’s 1911 transactions velocity func- tion, although few realize that it incorporates most of the same variables as Friedman’s.1 On velocity’s interest rate determinant, Fisher writes: “Each per- son regulates his turnover” to avoid “waste of interest” (1963, p. 152). When rates rise, cashholders “will avoid carrying too much” money thus prompting a rise in velocity. On expected inflation, he says: “When...depreciation is anticipated, there is a tendency among owners of money to spend it speedily . the result being to raise prices by increasing the velocity of circulation” (p. 263). And on real income: “The rich have a higher rate of turnover than the poor. They spend money faster, not only absolutely but relatively to the money they keep on hand. -

M1=100 Kg Adult, M2=10 Kg Baby. the Seesaw Starts from Rest. Which Direction Will It Rotates?

m1 m2 m1=100 kg adult, m2=10 kg baby. The seesaw starts from rest. Which direction will it rotates? (a) Counter-Clockwise (b) Clockwise ()(c) NttiNo rotation (d) Not enough information Effect of a Constant Net Torque 2.3 A constant non-zero net torque is exerted on a wheel. Which of the following quantities must be changing? 1. angular position 2. angular velocity 3. angular acceleration 4. moment of inertia 5. kinetic energy 6. the mass center location A. 1, 2, 3 B. 4, 5, 6 C. 1,2, 5 D. 1, 2, 3, 4 E. 2, 3, 5 1 Example: second law for rotation PP10601-50: A torque of 32.0 N·m on a certain wheel causes an angular acceleration of 25.0 rad/s2. What is the wheel's rotational inertia? Second Law example: α for an unbalanced bar Bar is massless and originally horizontal Rotation axis at fulcrum point L1 N L2 Î N has zero torque +y Find angular acceleration of bar and the linear m1gmfulcrum 2g acceleration of m1 just after you let go τnet Constraints: Use: τnet = Itotα ⇒ α = Itot 2 2 Using specific numbers: where: Itot = I1 + I2 = m1L1 + m2L2 Let m1 = m2= m L =20 cm, L = 80 cm τnet = ∑ τo,i = + m1gL1 − m2gL2 1 2 θ gL1 − gL2 g(0.2 - 0.8) What happened to sin( ) in moment arm? α = 2 2 = 2 2 L1 + L2 0.2 + 0.8 2 net = − 8.65 rad/s Clockwise torque m gL − m gL a ==+ -α L 1.7 m/s2 α = 1 1 2 2 11 2 2 Accelerates UP m1L1 + m2L2 total I about pivot What if bar is not horizontal? 2 See Saw 3.1. -

VELOCITY from Our Establishment in 1957, We Have Become One of the Oldest Exclusive Manufacturers of Commercial Flooring in the United States

VELOCITY From our establishment in 1957, we have become one of the oldest exclusive manufacturers of commercial flooring in the United States. As one of the largest privately held mills, our FAMILY-OWNERSHIP provides a heritage of proven performance and expansive industry knowledge. Most importantly, our focus has always been on people... ensuring them that our products deliver the highest levels of BEAUTY, PERFORMANCE and DEPENDABILITY. (cover) Velocity Move, quarter turn. (right) Velocity Move with Pop Rojo and Azul, quarter turn. VELOCITY 3 velocity 1814 style 1814 style 1814 style 1814 color 1603 color 1604 color 1605 position direction magnitude style 1814 style 1814 style 1814 color 1607 color 1608 color 1609 reaction move constant style 1814 color 1610 vector Velocity Vector, quarter turn. VELOCITY 5 where to use kinetex Healthcare Fitness Centers kinetex overview Acute care hospitals, medical Health Clubs/Gyms office buildings, urgent care • Cardio Centers clinics, outpatient surgery • Stationary Weight Centers centers, outpatient physical • Dry Locker Room Areas therapy/rehab centers, • Snack Bars outpatient imaging centers, etc. • Offices Kinetex® is an advanced textile composite flooring that combines key attributes of • Cafeteria, dining areas soft-surface floor covering with the long-wearing performance characteristics of • Chapel Retail / Mercantile hard-surface flooring. Created as a unique floor covering alternative to hard-surface Wholesale / Retail merchants • Computer room products, J+J Flooring’s Kinetex encompasses an unprecedented range of • Corridors • Checkout / cash wrap performance attributes for retail, healthcare, education and institutional environments. • Diagnostic imaging suites • Dressing rooms In addition to its human-centered qualities and highly functional design, Kinetex • Dry physical therapy • Sales floor offers a reduced environmental footprint compared to traditional hard-surface options. -

Chapter 3 Motion in Two and Three Dimensions

Chapter 3 Motion in Two and Three Dimensions 3.1 The Important Stuff 3.1.1 Position In three dimensions, the location of a particle is specified by its location vector, r: r = xi + yj + zk (3.1) If during a time interval ∆t the position vector of the particle changes from r1 to r2, the displacement ∆r for that time interval is ∆r = r1 − r2 (3.2) = (x2 − x1)i +(y2 − y1)j +(z2 − z1)k (3.3) 3.1.2 Velocity If a particle moves through a displacement ∆r in a time interval ∆t then its average velocity for that interval is ∆r ∆x ∆y ∆z v = = i + j + k (3.4) ∆t ∆t ∆t ∆t As before, a more interesting quantity is the instantaneous velocity v, which is the limit of the average velocity when we shrink the time interval ∆t to zero. It is the time derivative of the position vector r: dr v = (3.5) dt d = (xi + yj + zk) (3.6) dt dx dy dz = i + j + k (3.7) dt dt dt can be written: v = vxi + vyj + vzk (3.8) 51 52 CHAPTER 3. MOTION IN TWO AND THREE DIMENSIONS where dx dy dz v = v = v = (3.9) x dt y dt z dt The instantaneous velocity v of a particle is always tangent to the path of the particle. 3.1.3 Acceleration If a particle’s velocity changes by ∆v in a time period ∆t, the average acceleration a for that period is ∆v ∆v ∆v ∆v a = = x i + y j + z k (3.10) ∆t ∆t ∆t ∆t but a much more interesting quantity is the result of shrinking the period ∆t to zero, which gives us the instantaneous acceleration, a. -

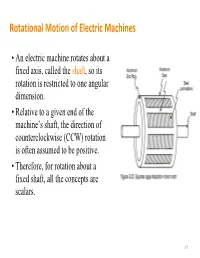

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines • An electric machine rotates about a fixed axis, called the shaft, so its rotation is restricted to one angular dimension. • Relative to a given end of the machine’s shaft, the direction of counterclockwise (CCW) rotation is often assumed to be positive. • Therefore, for rotation about a fixed shaft, all the concepts are scalars. 17 Angular Position, Velocity and Acceleration • Angular position – The angle at which an object is oriented, measured from some arbitrary reference point – Unit: rad or deg – Analogy of the linear concept • Angular acceleration =d/dt of distance along a line. – The rate of change in angular • Angular velocity =d/dt velocity with respect to time – The rate of change in angular – Unit: rad/s2 position with respect to time • and >0 if the rotation is CCW – Unit: rad/s or r/min (revolutions • >0 if the absolute angular per minute or rpm for short) velocity is increasing in the CCW – Analogy of the concept of direction or decreasing in the velocity on a straight line. CW direction 18 Moment of Inertia (or Inertia) • Inertia depends on the mass and shape of the object (unit: kgm2) • A complex shape can be broken up into 2 or more of simple shapes Definition Two useful formulas mL2 m J J() RRRR22 12 3 1212 m 22 JRR()12 2 19 Torque and Change in Speed • Torque is equal to the product of the force and the perpendicular distance between the axis of rotation and the point of application of the force. T=Fr (Nm) T=0 T T=Fr • Newton’s Law of Rotation: Describes the relationship between the total torque applied to an object and its resulting angular acceleration. -

Unit 1: Motion

Macomb Intermediate School District High School Science Power Standards Document Physics The Michigan High School Science Content Expectations establish what every student is expected to know and be able to do by the end of high school. They also outline the parameters for receiving high school credit as dictated by state law. To aid teachers and administrators in meeting these expectations the Macomb ISD has undertaken the task of identifying those content expectations which can be considered power standards. The critical characteristics1 for selecting a power standard are: • Endurance – knowledge and skills of value beyond a single test date. • Leverage - knowledge and skills that will be of value in multiple disciplines. • Readiness - knowledge and skills necessary for the next level of learning. The selection of power standards is not intended to relieve teachers of the responsibility for teaching all content expectations. Rather, it gives the school district a common focus and acts as a safety net of standards that all students must learn prior to leaving their current level. The following document utilizes the unit design including the big ideas and real world contexts, as developed in the science companion documents for the Michigan High School Science Content Expectations. 1 Dr. Douglas Reeves, Center for Performance Assessment Unit 1: Motion Big Ideas The motion of an object may be described using a) motion diagrams, b) data, c) graphs, and d) mathematical functions. Conceptual Understandings A comparison can be made of the motion of a person attempting to walk at a constant velocity down a sidewalk to the motion of a person attempting to walk in a straight line with a constant acceleration. -

Physics B Topics Overview ∑

Physics 106 Lecture 1 Introduction to Rotation SJ 7th Ed.: Chap. 10.1 to 3 • Course Introduction • Course Rules & Assignment • TiTopics Overv iew • Rotation (rigid body) versus translation (point particle) • Rotation concepts and variables • Rotational kinematic quantities Angular position and displacement Angular velocity & acceleration • Rotation kinematics formulas for constant angular acceleration • Analogy with linear kinematics 1 Physics B Topics Overview PHYSICS A motion of point bodies COVERED: kinematics - translation dynamics ∑Fext = ma conservation laws: energy & momentum motion of “Rigid Bodies” (extended, finite size) PHYSICS B rotation + translation, more complex motions possible COVERS: rigid bodies: fixed size & shape, orientation matters kinematics of rotation dynamics ∑Fext = macm and ∑ Τext = Iα rotational modifications to energy conservation conservation laws: energy & angular momentum TOPICS: 3 weeks: rotation: ▪ angular versions of kinematics & second law ▪ angular momentum ▪ equilibrium 2 weeks: gravitation, oscillations, fluids 1 Angular variables: language for describing rotation Measure angles in radians simple rotation formulas Definition: 360o 180o • 2π radians = full circle 1 radian = = = 57.3o • 1 radian = angle that cuts off arc length s = radius r 2π π s arc length ≡ s = r θ (in radians) θ ≡ rad r r s θ’ θ Example: r = 10 cm, θ = 100 radians Æ s = 1000 cm = 10 m. Rigid body rotation: angular displacement and arc length Angular displacement is the angle an object (rigid body) rotates through during some time interval..... ...also the angle that a reference line fixed in a body sweeps out A rigid body rotates about some rotation axis – a line located somewhere in or near it, pointing in some y direction in space • One polar coordinate θ specifies position of the whole body about this rotation axis. -

Exploring Robotics Joel Kammet Supplemental Notes on Gear Ratios

CORC 3303 – Exploring Robotics Joel Kammet Supplemental notes on gear ratios, torque and speed Vocabulary SI (Système International d'Unités) – the metric system force torque axis moment arm acceleration gear ratio newton – Si unit of force meter – SI unit of distance newton-meter – SI unit of torque Torque Torque is a measure of the tendency of a force to rotate an object about some axis. A torque is meaningful only in relation to a particular axis, so we speak of the torque about the motor shaft, the torque about the axle, and so on. In order to produce torque, the force must act at some distance from the axis or pivot point. For example, a force applied at the end of a wrench handle to turn a nut around a screw located in the jaw at the other end of the wrench produces a torque about the screw. Similarly, a force applied at the circumference of a gear attached to an axle produces a torque about the axle. The perpendicular distance d from the line of force to the axis is called the moment arm. In the following diagram, the circle represents a gear of radius d. The dot in the center represents the axle (A). A force F is applied at the edge of the gear, tangentially. F d A Diagram 1 In this example, the radius of the gear is the moment arm. The force is acting along a tangent to the gear, so it is perpendicular to the radius. The amount of torque at A about the gear axle is defined as = F×d 1 We use the Greek letter Tau ( ) to represent torque.