Islands of Effective International Adjudication: Constructing an Intellectual Property Rule of Law in the Andean Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collective Identity in the Andean Community: an Institutional Account*

Collective Identity in the Andean Community: An Institutional Account* Identidad colectiva en la comunidad andina: una aproximación institucional Germán Camilo Prieto** Recibido: 15/05/2015 Aprobado: 14/07/2015 Disponible en línea: 30/11/2015 Abstract Resumen This article assesses the ways in which regional Este artículo evalúa la forma en que las institu- institutions, understood as norms and institu- ciones regionales, entendidas como las normas y tional bodies, contribute to the formation of los órganos institucionales, contribuyen a la for- collective identity in the Andean Community mación de identidad colectiva en la Comunidad (AC). Departing from the previous existence Andina (CAN). Partiendo de la existencia previa of an Andean identity, grounded on historical de una identidad andina, basada en elementos and cultural issues, the paper takes three case históricos y culturales, el artículo toma tres studies to show the terms in which regional estudios de caso para mostrar los términos en institutions contribute to the formation of three que las instituciones regionales contribuyen a la dimensions of collective identity in the AC. formación de tres dimensiones de la identidad Namely, these are the cultural, ideological, and colectiva en la CAN, a saber: la dimensión cul- inter-group dimensions. The paper shows that tural, la ideológica y la intergrupal. Este trabajo although the ideas held about an Andean collec- muestra que aunque las ideas de una identidad tive identity by state representatives and Andean colectiva Andina que tienen los funcionarios doi:10.11144/Javeriana.papo20-2.ciac * Artículo de investigación. The present article is based on a paper presented at the XXII IPSA World Congress, Madrid 2012, at the Panel “Theorising the Role of Identity in the Unfolding of Regionalism: Comparative Perspectives”. -

Politics and Poverty in the Andean Region

Politics and Poverty in the Andean Region Policy Summary: Key Findings and Recommendations Politics and Poverty in the Andean Region Policy Summary: Key Findings and Recommendations Programme developed by International IDEA and Asociación Civil Transparencia Politics and Poverty in the Andean Region Policy Summary: Key Findings and Recommendations Co-editors Gustavo Guerra-García Kristen Sample Javier Alarcón Cervera Vanessa Cartaya José Luis Exeni Pedro Francke Haydée García Velásquez Claudia Giménez Francisco Herrero Carlos Meléndez Guerrero Gabriele Merz Gabriel Murillo Luís Javier Orjuela Michel Rowland García Alfredo Sarmiento Gómez Politics and Poverty in the Andean Region Policy Summary: Key Findings and Recommendations International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance 2008 Asociación Civil Transparencia 2008 International IDEA and Asociación Civil Transparencia publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA and Asociación Civil Transparencia, its Board or its Council members. AAAAAA Applications for permission to reproduce or translate all or any part of this publication should be made to: International IDEA aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa SE 103 34 Stockholm aaaaaaaiaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa Sweden aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa International -

The Role of Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) in the Global Energy Scenario

XLVII Meeting of Ministers | Buenos Aires, Argentina | 6 December | 2017 The Role of Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) in the Global Energy Scenario Panel of High Authorities Dr Sun Xiansheng Secretary General, IEF Riyadh Overview • Global trends and transformations • Observations on Latin America and the Caribbean • Key mile stones going forward Fossil share remains at 57% and 79% to 2040 in IEA and OPEC outlooks World Primary Energy Fuel Shares in 2014 and Outlook for 2040 Transition involves deep transformations IEA and IRENAIEA and OPEC Scenarios World Primary break Energy Shares.with andmain joint IRENAtrends-IEA Perspectives for the Energy Transition 1% 1% 4% 6% 12% 5% 6% 7% 16% 21% 100% 10% 10% 9% 2% 11% 10% 11% 2% 3% 12% 90% 3% 3% 3% 16% 3% 18% 80% 5% 5% 5% 4% 6% 21% 21% 22% 7% 7% 24% 8% 27% 4% 70% 24% 26% 31% 31% 25% 11% 5% 60% 28% 27% 26% 13% 22% 26% 50% 25% 14% 20% 40% 22% Fossil Fossil 29% 28% 27% 18% 17% 30% 23% 24% 22% 21% 12% Fossil 20% 13% 10% 9% 10% 0% IEA OPEC IEA CPS IEA NPS IEA 450 OPEC Ref OPEC A OPEC B IEA/IRENA IEA/IRENA 2014 2040 2050 Coal Oil Gas Nuclear Hydro Biomass Other renewables IEF Comparative Analysis Sources: IEF-Resources for the Future Introductory Paper for the Sixth IEA-IEF-OPEC Symposium on Energy Outlooks February 2016, OECD/IEA and IRENA 2017 Perspectives for the Energy Transition (66% 20Celsius Scenario), OECD/IEA WEO 2016. OPEC WOO 2016 South America is a green power house already Non-fossil shares are well above 50% in key regions Installed Power Capacity by Energy Source 100% 9% 11% 8% 90% 19% 80% 42% 51% 70% 47% 42% 60% 68% 44% 50% 40% 3% 23% 41% 30% 41% 20% 38% 27% 9% 23% 10% 8% 9% 6% 0% 3% 4% Andean States Caribbean Central America Southern Cone Brazil Mexico Coal Oil and Diesel Natural Gas Nuclear Hydro Wind Other renewables Non-Fossil Share IEF Analysis of Inter-American Development Bank Data, (2016) Balza, Lenin. -

Reports on Completed Research for 2018

Reports on Completed Research For 2018 “Supporting worldwide research in all branches of Anthropology” REPORTS ON COMPLETED RESEARCH The following research projects, supported by Foundation grants, were reported as complete during 2018. The reports are listed by subdiscipline, then geographic area (where applicable) and in alphabetical order. A Bibliography of Publications resulting from Foundation- supported research (reported over the same period) follows, along with an Index of Grantees Reporting Completed Research. ARCHAEOLOGY Africa: DR. BENJAMIN R. COLLINS, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, was awarded a grant in October 2015 to aid research on “Late MIS 3 Behavioral Diversity: The View from Grassridge Rockshelter, Eastern Cape, South Africa.” The Grassridge Archaeological and Palaeoenvironmental Project (GAPP) contributes to understanding how hunter-gatherers adapted to periods of rapid and unpredictable climate change during the past 50,000 years. Specifically, GAPP focuses on excavation and research at Grassridge Rockshelter, located in the understudied interior grasslands of southern Africa, to explore the changing nature of social landscapes during this period through comparative studies of technological strategies, subsistence strategies, and other cultural behaviors. Recent excavations at Grassridge have produced a rich cultural record of hunter-gatherer life at the site ~40,000 to 35,000 years ago, which provides insight into the production of stone tools for hunting, the use of local plants for bedding and matting, and the use of ochre. This research suggests that the hunter-gatherers at Grassridge were well-adapted to their local environment, and that their particular suite of adaptive strategies may have differed from hunter-gatherer groups in other regions of southern Africa. -

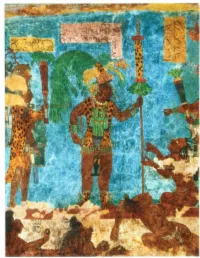

CHAPTER 4 EARLY SOCIETIES in the AMERICAS and OCEANIA 69 G 11/ F of M C \I C O ' C Hi Ch~N B A

n early September of the year 683 C. E., a Maya man named Chan Bahlum grasped a sharp obsidian knife and cut three deep slits into the skin of his penis. He insert ed into each slit a strip of paper made from beaten tree bark so as to encourage a continuing flow of blood. His younger brother Kan Xu I performed a similar rite, and other members of his family also drew blood from their own bodies. The bloodletting observances of September 683 c.E. were political and religious rituals, acts of deep piety performed as Chan Bahlum presided over funeral services for his recently deceased father, Pacal, king of the Maya city of Palenque in the Yu catan peninsula. The Maya believed that the shedding of royal blood was essential to the world's survival. Thus, as Chan Bahlum prepared to succeed his father as king of Palenque, he let his blood flow copiously. Throughout Mesoamerica, Maya and other peoples performed similar rituals for a millennium and more. Maya rulers and their family members regularly spilled their own blood. Men commonly drew blood from the penis, like Chan Bahlum, and women often drew from the tongue. Both sexes occasionally drew blood also from the earlobes, lips, or cheeks, and they sometimes increased the flow by pulling long, thick cords through their wounds. According to Maya priests, the gods had shed their own blood to water the earth and nourish crops of maize, and they expected human beings to honor them by imitating their sacrifice. By spilling human blood the Maya hoped to please the gods and ensure that life-giving waters would bring bountiful harvests to their fields. -

Docudlenting 12,000 Years of Coastal Occupation on the Osdlore Littoral, Peru

227 DocuDlenting 12,000 Years of Coastal Occupation on the OSDlore Littoral, Peru Susan D. deFrance University of Florida Gainesville, Florida Nicci Grayson !(aren Wise Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History Los Angeles, California The history of coastal settlement in Peru beginning ca. 12)000 years ago provides insight into maritime adaptations and regional specialization. we document the Late Paleoindian to Archaic occupational history along the Osmore River coastalplain near 110 with 95 radiocarbon dates from eight sites. Site distribution suggests that settlement shifted linearly along the coast)possibly in relation to the productivity of coastal springs. Marine ftods) raw materials) and freshwater were sufficient to sustain coastalftragers ftr over 12 millennia. Despite climatic changes at the end of the Pleistocene and during the Middle Holocene) we ftund no evidenceftr a hiatus in coastal occupation) in contrast toparts of highland north- ern Chile and areas of coastal Peru ftr the same time period. Coastal abandonment was a localized phenomenon rather than one that occurred acrossvast areas of the South Central Andean littoral. Our finds suggest that regional adaptation to specifichabitats began with initial colonization and endured through time. Introduction southern Peru. This region was not a center of civilization in preceramic or subsequent times, but the seaboard was One of the world's richest marine habitats stretching colonized in the Late Pleistocene and has a long archaeo- along the desert littoral of the Central Andes contributed logical record. The Central Andean coast is adjacent to one significantly to the early florescence of prepottery civiliza- of the richest marine habitats in the world. -

Andean Community of Nations

5(*,21$/675$7(*<$1'($1&20081,7<2)1$7,216 1 $FURQ\PV1 ACT Amazonian Cooperation Treaty AEC Project for the establishment of an common external tariff for the Andean States AIS Andean Integration System (comprises all the Andean regional institutions) ALADI Latin American Integration Association (Member States of Mercosur, the Andean Pact and Mexico, Chile and Cuba) ALALC Latin American Free Trade Association, replaced by ALADI in 1980 ALA Reg. Council Regulation (EEC) No 443/92 of 25 February 1992 on technical and financial and economic cooperation with the countries of Asia and Latin America ALFA Latin American Academic Training Programme ALINVEST Latin American investment programme for the promotion of relations between SMEs @LIS Latin American Information Society Programme APEC Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (21 members)2 APIR Project for the acceleration of the regional integration process ARIP Andean Regional Indicative Programme ATPA Andean Trade Preference Act CACM Central American Common Market: Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua and Honduras CAF Andean Development Corporation CALIDAD Andean regional project on quality standards CAN Andean Community of Nations: Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela + AIS CAPI Andean regional project for the production of agricultural and industrial studies CARICOM3 Caribbean Community DAC Development Assistance Committee of the OECD DC Developing country DFI Direct foreign investment DG Directorate-General DIPECHO ECHO Disaster Preparedness Programme EC European Community ECHO -

LAH: Latin American History Courses 1

LAH: Latin American History Courses 1 LAH 4474 The Colonial Caribbean LAH: Latin American Col of Arts, Soc Sci and Human, Department of History and Philosophy History Courses 3 sh (may not be repeated for credit) This course introduces students to the colonial Caribbean, from first contact in 1492 to emancipations in the British Islands in the 1830's. Courses The emphasis throughout is on the Anglophone colonies, though we will cover the early Spanish dominance, African migrations, and the LAH 4131 'Atlantic Indians': How Indigenous and African revolution on French St. Domingue. Peoples Shaped Europe & the Americas Col of Arts, Soc Sci and Human, Department of History and Philosophy LAH 4522 The Andes: From the Incas to Today Col of Arts, Soc Sci and Human, Department of History and Philosophy 3 sh (may not be repeated for credit) 3 sh (may not be repeated for credit) The trajectories of European and Native American cultures and societies were enmeshed after 1492. Soldiers, colonists, missionaries, This course follows the development of the Andean region (Venezuela, readers, and consumers were profoundly affected by their exposure to Colombia, Bolivia, Peru, Chile, and Argentina), from the Spanish radically different ways of organizing life, and these effects permeated conquest of the Incan Empire to the fall of the military dictatorships of European culture. This course then takes seriously indigenous men the late 20th century. It examines the formation of the Spanish colonies and women as participants-not merely as objects-in the re-making of and their transition to independent nation-states, though many still intellectual history in the Atlantic world. -

Unfinished States

2 Unfinished States Historical Perspectives on the Andes JEREMY ADELMAN NDEAN STATES ARE, MORE THAN MOST COUNTRIES, Aworks in progress. Formed states are a species of political system in which subjects accept and are able to live by some set of basic ground rules and norms governing public affairs. Being finished need not imply an end to politics or history, but simply that a significant majority of a country’s population acknowledges the legitimacy of ruling systems and especially the rules that determine how rules are supposed to change. For historical reasons, this is not the case in the Andes. In Colombia, Peru, and Venezuela (the countries analyzed in this chapter), important swaths of societies either do not accept some underlying rules or could not live by them even if they did accept them. This is not a recent prob- lem. Indeed, one of the principal difficulties facing Colombians, Peru- vians, and Venezuelans is that they cannot easily turn to a golden (and often mythic) age of stateness. Each Andean republic bears the imprint of earlier struggles involving the definition of statehood from the nineteenth century, conflicts that have expressed themselves in different but still 41 42 JEREMY ADELMAN unsettled outcomes to the present. This long-term historical process dis- tinguishes the Andes from other regions in Latin America, from Mexico to the Southern Cone, where consolidated models of order and development (punctuated, to be sure, by moments of upheaval) prevailed for enough time to remap the human landscape within each country and to furnish these countries with the means to cope with the manifold pressures of globalization, yawning inequities, or the misfortunes wrought by lousy leadership. -

REGIONALISM and INTERREGIONALISM in LATIN AMERICA: the Beginning Or the End of Latin America’S ‘Continental Integration’?

20 REGIONALISM AND INTERREGIONALISM IN LATIN AMERICA: The Beginning or the End of Latin America’s ‘Continental Integration’? Paul Isbell Centre for Transatlantic Relations Johns Hopkins University-SAIS Kimberly A. Nolan García Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas (CIDE) ABSTRACT This paper investigates the development of regionalism and inter-regionalism in Latin America as pertains to trade relations, one of the key drivers of regional integration in the region. The paper develops the outlines of the thesis that ‘Latin America’ or ‘South America’ no longer provide the optimal geography for constituting an appropriate region, and that new 'ocean basin regions' offer more promising regional and interregional trajectories for Latin American countries to pursue than do their currently conceived land-based ‘trade regions’. By ‘re- mapping’ national figures for bilateral commercial trade culled from the UNCOMTRADE data set, we provide initial quantitative evidence of new Latin American regional trade dynamics emerging within the continent’s two flanking ocean basin regions – the Pacific Basin and the Atlantic Basin – where new forms of ‘non-hegemonic’ and ‘maritime-centered’ regionalisms are being articulated and developed. The paper concludes that new ‘ocean basin regionalisms’ offer Latin America alternative options for pursuing regional trade agreements and other forms of inter-regional trade integration which, while remaining complementary to the current sub-continental and continental regionalisms, and could become a new guiding frame for Latin American regionalism. [The first draft of this Scientific Paper was presented at the ATLANTIC FUTURE seminar in Lisbon, April 2015.] 1 ATLANTIC FUTURE SCIENTIFIC PAPER 20 Table of contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................... 3 2. -

World Heritage 27 COM

World Heritage 27 COM Distribution limited WHC-03/27.COM/13 Paris, 19 June 2003 Original : English/French UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE Twenty-seventh session Paris, UNESCO Headquarters, Room XII 30 June - 5 July 2003 Item 13 of the Provisional Agenda: Implementation of the Global Strategy SUMMARY This document contains: I. Background information II. Summary table III. Regional Progress Reports (2002-2003) and Action Plans (2004-2005) IV. Draft Decisions Decision required: the Committee is requested to examine the Draft Decisions on pages 18-19 of this document. I.. BACKGROUND 1.1 Although the Global Strategy for a representative, balanced and credible World Heritage List was adopted by the World Heritage Committee at its 18th session (Phuket, 1994)1, it was only in 1998 that the Committee, at its 22nd session (Kyoto, 1998), examined Regional Global Strategy Action Plans2. 1.2 Following the 22nd session of the Committee, the Secretariat prepared progress reports on the Regional Action Plans for examination by the World Heritage Committee3. The Action Plans focus primarily on Capacity Building. 1.3. Thus the aim of this Progress Report is to provide the Committee with an update on the activities undertaken in 2002 and 2003 as part of the Regional Actions for the implementation of a Global Strategy approved by the Committee at its 25th session (Helsinki, 2001)4 and to propose activities to be carried out in 2004-2005. The action plans proposed for 2004-2005 will need to be financed through the Regional Programmes (see WHC-03/27.COM/20B), the Preparatory Assistance from the World Heritage Fund-International Assistance and other extrabudgetary sources in view of the limited budget of the 2004-2005 World Heritage Fund. -

Mining and Institutional Frameworks in the Andean Region

Mining and Institutional Frameworks in the Andean Region. The Super Cycle and its Legacy, or the Difficult Relationships between Policies to Promote Mining and Hydrocarbon Investment and Institutional Reforms in the Andean Region Eduardo Ballón and Raúl Molina (consultants) Claudia Viale and Carlos Monge (NRGI Latin America) Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Natural Resource Governance Institute Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH Latin America Office 2 Mining and Institutional Frameworks in the Andean Region Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) Carlos Monge Salgado Index Regional Director for Latin America Avenida del Ejército 250, Oficina 305 Lima 18, Perú Teléfono (+51) 1-2775146 [email protected] www.resourcegovernance.org Presentation 1 With the support of: 1. Analytical and methodological framework 3 Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale 3 Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH 1.1 Working hypotheses Program “Regional cooperation for sustainable 1.2. Conceptual framework 3 management of mining resources “ 1.3 Selected State reform processes 10 Federico Froebel 1776, Providencia. Santiago de Chile. 1.4 The countries considered 13 www.giz.de 2. Extractive industries in Latin America during On behalf of the Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development the super cycle 15 (BMZ) from Germany. 2.1 A general appreciation 15 20 Mining and institutional frameworks in the 2.2 A look at each component Andean Region. The super cycle and its legacy, or the difficult relationships between 3. Democratization and modernization: the policies to promote mining and hydrocarbon investment and institutional reforms in the national cases 26 Andean Region 3.1 Decentralization, civic participation and the building of an environmental institutionality 27 March, 2017 This report was prepared by the NRGI based 4.