US Policy in the Andes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collective Identity in the Andean Community: an Institutional Account*

Collective Identity in the Andean Community: An Institutional Account* Identidad colectiva en la comunidad andina: una aproximación institucional Germán Camilo Prieto** Recibido: 15/05/2015 Aprobado: 14/07/2015 Disponible en línea: 30/11/2015 Abstract Resumen This article assesses the ways in which regional Este artículo evalúa la forma en que las institu- institutions, understood as norms and institu- ciones regionales, entendidas como las normas y tional bodies, contribute to the formation of los órganos institucionales, contribuyen a la for- collective identity in the Andean Community mación de identidad colectiva en la Comunidad (AC). Departing from the previous existence Andina (CAN). Partiendo de la existencia previa of an Andean identity, grounded on historical de una identidad andina, basada en elementos and cultural issues, the paper takes three case históricos y culturales, el artículo toma tres studies to show the terms in which regional estudios de caso para mostrar los términos en institutions contribute to the formation of three que las instituciones regionales contribuyen a la dimensions of collective identity in the AC. formación de tres dimensiones de la identidad Namely, these are the cultural, ideological, and colectiva en la CAN, a saber: la dimensión cul- inter-group dimensions. The paper shows that tural, la ideológica y la intergrupal. Este trabajo although the ideas held about an Andean collec- muestra que aunque las ideas de una identidad tive identity by state representatives and Andean colectiva Andina que tienen los funcionarios doi:10.11144/Javeriana.papo20-2.ciac * Artículo de investigación. The present article is based on a paper presented at the XXII IPSA World Congress, Madrid 2012, at the Panel “Theorising the Role of Identity in the Unfolding of Regionalism: Comparative Perspectives”. -

Politics and Poverty in the Andean Region

Politics and Poverty in the Andean Region Policy Summary: Key Findings and Recommendations Politics and Poverty in the Andean Region Policy Summary: Key Findings and Recommendations Programme developed by International IDEA and Asociación Civil Transparencia Politics and Poverty in the Andean Region Policy Summary: Key Findings and Recommendations Co-editors Gustavo Guerra-García Kristen Sample Javier Alarcón Cervera Vanessa Cartaya José Luis Exeni Pedro Francke Haydée García Velásquez Claudia Giménez Francisco Herrero Carlos Meléndez Guerrero Gabriele Merz Gabriel Murillo Luís Javier Orjuela Michel Rowland García Alfredo Sarmiento Gómez Politics and Poverty in the Andean Region Policy Summary: Key Findings and Recommendations International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance 2008 Asociación Civil Transparencia 2008 International IDEA and Asociación Civil Transparencia publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA and Asociación Civil Transparencia, its Board or its Council members. AAAAAA Applications for permission to reproduce or translate all or any part of this publication should be made to: International IDEA aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa SE 103 34 Stockholm aaaaaaaiaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa Sweden aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa International -

The Role of Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) in the Global Energy Scenario

XLVII Meeting of Ministers | Buenos Aires, Argentina | 6 December | 2017 The Role of Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) in the Global Energy Scenario Panel of High Authorities Dr Sun Xiansheng Secretary General, IEF Riyadh Overview • Global trends and transformations • Observations on Latin America and the Caribbean • Key mile stones going forward Fossil share remains at 57% and 79% to 2040 in IEA and OPEC outlooks World Primary Energy Fuel Shares in 2014 and Outlook for 2040 Transition involves deep transformations IEA and IRENAIEA and OPEC Scenarios World Primary break Energy Shares.with andmain joint IRENAtrends-IEA Perspectives for the Energy Transition 1% 1% 4% 6% 12% 5% 6% 7% 16% 21% 100% 10% 10% 9% 2% 11% 10% 11% 2% 3% 12% 90% 3% 3% 3% 16% 3% 18% 80% 5% 5% 5% 4% 6% 21% 21% 22% 7% 7% 24% 8% 27% 4% 70% 24% 26% 31% 31% 25% 11% 5% 60% 28% 27% 26% 13% 22% 26% 50% 25% 14% 20% 40% 22% Fossil Fossil 29% 28% 27% 18% 17% 30% 23% 24% 22% 21% 12% Fossil 20% 13% 10% 9% 10% 0% IEA OPEC IEA CPS IEA NPS IEA 450 OPEC Ref OPEC A OPEC B IEA/IRENA IEA/IRENA 2014 2040 2050 Coal Oil Gas Nuclear Hydro Biomass Other renewables IEF Comparative Analysis Sources: IEF-Resources for the Future Introductory Paper for the Sixth IEA-IEF-OPEC Symposium on Energy Outlooks February 2016, OECD/IEA and IRENA 2017 Perspectives for the Energy Transition (66% 20Celsius Scenario), OECD/IEA WEO 2016. OPEC WOO 2016 South America is a green power house already Non-fossil shares are well above 50% in key regions Installed Power Capacity by Energy Source 100% 9% 11% 8% 90% 19% 80% 42% 51% 70% 47% 42% 60% 68% 44% 50% 40% 3% 23% 41% 30% 41% 20% 38% 27% 9% 23% 10% 8% 9% 6% 0% 3% 4% Andean States Caribbean Central America Southern Cone Brazil Mexico Coal Oil and Diesel Natural Gas Nuclear Hydro Wind Other renewables Non-Fossil Share IEF Analysis of Inter-American Development Bank Data, (2016) Balza, Lenin. -

Remarks by Otto Reich, Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs, at the Center for Strategic and International Studies

REMARKS BY OTTO REICH, ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WESTERN HEMISPHERE AFFAIRS, AT THE CENTER FOR STRATEGIC AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES TOPIC: U.S. FOREIGN POLICY IN THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE LOCATION: WILLARD INTERCONTINENTAL HOTEL, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 8:35 A.M. EST DATE: TUESDAY, MARCH 12, 2002 (Applause.) MR. REICH: Well, I didn't expect quite this many people either, but it's nice to see so many friends, former colleagues, unindicted coconspirators. (Laughter.) That was supposed to get a better laugh than that. (Laughter.) That was a joke. (Laughter.) It is good to be back at CSIS. As John Hamre said, I go back quite a ways at CSIS -- actually 1971. I was getting my masters at Georgetown University, and the late Jim Theberge (ph) was director of the Latin American program at CSIS, which was, at that time, still associated with Georgetown. And there was a contest or requests for proposals, or whatever you want to call it, for two Ph.D. theses and one masters thesis. And not being a scholar, frankly, I didn't think I had much of a chance. But somebody said, "Look, you might as well apply, submit a masters thesis proposal, and you get a fellowship if you are selected." Well, I was selected. And, frankly, I think that changed my career considerably, because I did spend a little bit more time studying than I had been. I had to give up a little tennis in the process. But as a result of that and many other very fortunate turns in the road, I am now in this position, and I get to speak to a group of people who know more about this subject than I do. -

International Drug Control Hearing

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. /SIJ.~fo3 S. HRG. 101-591 INTERNATIONAL DRUG CONTROL HEARING BEFORE THE OOMMITTEE ON THE JI.IDIOIARX UNITED STATES aENATJR (CiNE HyNDRED FIR§YCONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON • THE CONTROL OF FOREIGN DRUG TRAFFICKING ACTIVITIES AUGUST 17, 1989 Serial No. J-101-38 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary NCJRS mIN 9 1995 ~ ACQUISITIONS • ~'J. U.s. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE • 2R-05:l WASHINGTON: 1990 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 . n r r-"'l f .. ' COMMI'ITEE ON THE JUDICIARY JOSEPH R. BIOEN, JR., Delaware, Chairman EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts STROM THURMOND, South Carolina HOWARD M. METZENBAUM, Ohio ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah DENNIS DECONCINI, Arizona ALAN K. SIMPSON, Wyoming • PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa HOWELL HEFLIN, Alabama ARLEN SPEGrER, Pennsylvania PAUL SIMON, Illinois GORDON J. HUMPHREY, New Hampshire HERBERT KOHL, Wisconsin RONALD A. KLAIJo!, Chief Counsel DIANA HUFFMAN, Staff Director JEFFREY J. PECK, General Counsel TERRY L, WOOTEN, Minority Chief Counsel and Staff Director (II) 154863 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the p~rson or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this doc.ument are thos~ of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or poh<'les of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this ""'iJlllaiit'material has been granted by .. Public D::main u.s. -

Obstacles Offset Advances for Human Rights in Guatemala by Adriana Beltrán

CrossCurrents NEWSLETTER OF THE WASHINGTON OFFICE ON LATIN AMERICA • DECEMBER 2002 Obstacles Offset Advances for Human Rights in Guatemala By Adriana Beltrán espite recent court decisions in two high profile human rights cases, the Guatemalan human rights situation has deteriorated. On DOctober 3, 2002, twelve years after the bloody murder of renowned Guatemalan anthropologist Myrna Mack Chang, a three-judge tribunal sentenced Col. Juan Valencia Osorio to thirty years imprisonment for orchestrating her murder, and acquitted his co-defendants Gen. Augusto Godoy Gaitán and Col. Juan Guillermo Oliva Carrera. The defendants were members of the notorious Presidential High Command (Estado Mayor Presidencial – EMP), a unit responsible for numerous human rights violations during the country’s internal armed conflict, according to the UN- sponsored Historical Clarification Commission and the Catholic Church’s Recovery of the Historical Memory Project (REHMI). This landmark conviction, and the verdicts in the case of Bishop Juan Gerardi in 2001, in which three military officers of the EMP were convicted for his murder, do set a precedent for the pursuit of justice in other human rights cases that have remained stalled within Guatemala’s justice system. IN THIS ISSUE The convictions in the Mack and Gerardi cases are breakthroughs because for the first time judicial tribunals convicted military officers for political crimes committed during and after the internal conflict respectively. But Venezuela’s Political Crisis: while the decision to convict in both cases is an important step toward A joint statement by the accountability, the cases clearly illustrate the major challenges that remain Washington Office on Latin in the fight against impunity. -

Reports on Completed Research for 2018

Reports on Completed Research For 2018 “Supporting worldwide research in all branches of Anthropology” REPORTS ON COMPLETED RESEARCH The following research projects, supported by Foundation grants, were reported as complete during 2018. The reports are listed by subdiscipline, then geographic area (where applicable) and in alphabetical order. A Bibliography of Publications resulting from Foundation- supported research (reported over the same period) follows, along with an Index of Grantees Reporting Completed Research. ARCHAEOLOGY Africa: DR. BENJAMIN R. COLLINS, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, was awarded a grant in October 2015 to aid research on “Late MIS 3 Behavioral Diversity: The View from Grassridge Rockshelter, Eastern Cape, South Africa.” The Grassridge Archaeological and Palaeoenvironmental Project (GAPP) contributes to understanding how hunter-gatherers adapted to periods of rapid and unpredictable climate change during the past 50,000 years. Specifically, GAPP focuses on excavation and research at Grassridge Rockshelter, located in the understudied interior grasslands of southern Africa, to explore the changing nature of social landscapes during this period through comparative studies of technological strategies, subsistence strategies, and other cultural behaviors. Recent excavations at Grassridge have produced a rich cultural record of hunter-gatherer life at the site ~40,000 to 35,000 years ago, which provides insight into the production of stone tools for hunting, the use of local plants for bedding and matting, and the use of ochre. This research suggests that the hunter-gatherers at Grassridge were well-adapted to their local environment, and that their particular suite of adaptive strategies may have differed from hunter-gatherer groups in other regions of southern Africa. -

CHAPTER 4 EARLY SOCIETIES in the AMERICAS and OCEANIA 69 G 11/ F of M C \I C O ' C Hi Ch~N B A

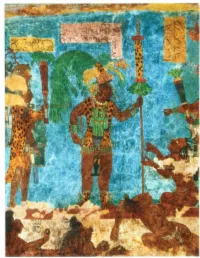

n early September of the year 683 C. E., a Maya man named Chan Bahlum grasped a sharp obsidian knife and cut three deep slits into the skin of his penis. He insert ed into each slit a strip of paper made from beaten tree bark so as to encourage a continuing flow of blood. His younger brother Kan Xu I performed a similar rite, and other members of his family also drew blood from their own bodies. The bloodletting observances of September 683 c.E. were political and religious rituals, acts of deep piety performed as Chan Bahlum presided over funeral services for his recently deceased father, Pacal, king of the Maya city of Palenque in the Yu catan peninsula. The Maya believed that the shedding of royal blood was essential to the world's survival. Thus, as Chan Bahlum prepared to succeed his father as king of Palenque, he let his blood flow copiously. Throughout Mesoamerica, Maya and other peoples performed similar rituals for a millennium and more. Maya rulers and their family members regularly spilled their own blood. Men commonly drew blood from the penis, like Chan Bahlum, and women often drew from the tongue. Both sexes occasionally drew blood also from the earlobes, lips, or cheeks, and they sometimes increased the flow by pulling long, thick cords through their wounds. According to Maya priests, the gods had shed their own blood to water the earth and nourish crops of maize, and they expected human beings to honor them by imitating their sacrifice. By spilling human blood the Maya hoped to please the gods and ensure that life-giving waters would bring bountiful harvests to their fields. -

Docudlenting 12,000 Years of Coastal Occupation on the Osdlore Littoral, Peru

227 DocuDlenting 12,000 Years of Coastal Occupation on the OSDlore Littoral, Peru Susan D. deFrance University of Florida Gainesville, Florida Nicci Grayson !(aren Wise Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History Los Angeles, California The history of coastal settlement in Peru beginning ca. 12)000 years ago provides insight into maritime adaptations and regional specialization. we document the Late Paleoindian to Archaic occupational history along the Osmore River coastalplain near 110 with 95 radiocarbon dates from eight sites. Site distribution suggests that settlement shifted linearly along the coast)possibly in relation to the productivity of coastal springs. Marine ftods) raw materials) and freshwater were sufficient to sustain coastalftragers ftr over 12 millennia. Despite climatic changes at the end of the Pleistocene and during the Middle Holocene) we ftund no evidenceftr a hiatus in coastal occupation) in contrast toparts of highland north- ern Chile and areas of coastal Peru ftr the same time period. Coastal abandonment was a localized phenomenon rather than one that occurred acrossvast areas of the South Central Andean littoral. Our finds suggest that regional adaptation to specifichabitats began with initial colonization and endured through time. Introduction southern Peru. This region was not a center of civilization in preceramic or subsequent times, but the seaboard was One of the world's richest marine habitats stretching colonized in the Late Pleistocene and has a long archaeo- along the desert littoral of the Central Andes contributed logical record. The Central Andean coast is adjacent to one significantly to the early florescence of prepottery civiliza- of the richest marine habitats in the world. -

Andean Community of Nations

5(*,21$/675$7(*<$1'($1&20081,7<2)1$7,216 1 $FURQ\PV1 ACT Amazonian Cooperation Treaty AEC Project for the establishment of an common external tariff for the Andean States AIS Andean Integration System (comprises all the Andean regional institutions) ALADI Latin American Integration Association (Member States of Mercosur, the Andean Pact and Mexico, Chile and Cuba) ALALC Latin American Free Trade Association, replaced by ALADI in 1980 ALA Reg. Council Regulation (EEC) No 443/92 of 25 February 1992 on technical and financial and economic cooperation with the countries of Asia and Latin America ALFA Latin American Academic Training Programme ALINVEST Latin American investment programme for the promotion of relations between SMEs @LIS Latin American Information Society Programme APEC Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (21 members)2 APIR Project for the acceleration of the regional integration process ARIP Andean Regional Indicative Programme ATPA Andean Trade Preference Act CACM Central American Common Market: Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua and Honduras CAF Andean Development Corporation CALIDAD Andean regional project on quality standards CAN Andean Community of Nations: Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela + AIS CAPI Andean regional project for the production of agricultural and industrial studies CARICOM3 Caribbean Community DAC Development Assistance Committee of the OECD DC Developing country DFI Direct foreign investment DG Directorate-General DIPECHO ECHO Disaster Preparedness Programme EC European Community ECHO -

Testimony of the Hon. Otto J. Reich President, Otto Reich Associates

Testimony of The Hon. Otto J. Reich President, Otto Reich Associates, LLC Presented Before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs March 25, 2014 “US Disengagement from Latin America: Compromised Security and Economic Interests.” Mr. Chairman and Members of the Committee: I thank you for the opportunity t0 come before this Committee once again to address a phenomenon that, if ignored, could threaten the security of our country: the increasing anti- Americanism and radicalization of some governments in the region, and the lack of effective response by our government. In the past few years the US government has neglected parts of the western hemisphere while adopting a misguided approach toward others. For example, in 2009 the Obama Administration seemed more determined to reach out to unfriendly governments such as Cuba, Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador, than to friendlier states, such as Mexico, Colombia, Peru and Chile. That sent confusing signals to friend and foe alike. Some say that the Administration believed that if it could get our adversaries to just listen to our earnest message, then they would stop their hostile behavior. That is not diplomacy; that is self-delusion. As we have seen with Russia, North Korea, Syria and Iran, wishful thinking does not make for an effective foreign policy. The same reasoning applies in our part of the world. For example, in its first year in office the Obama Administration unilaterally lifted financial sanctions against the military dictatorship in Cuba, thus allowing the Castro brothers to capture several billion dollars per year in travel and remittances that had been previously denied their regime. -

LAH: Latin American History Courses 1

LAH: Latin American History Courses 1 LAH 4474 The Colonial Caribbean LAH: Latin American Col of Arts, Soc Sci and Human, Department of History and Philosophy History Courses 3 sh (may not be repeated for credit) This course introduces students to the colonial Caribbean, from first contact in 1492 to emancipations in the British Islands in the 1830's. Courses The emphasis throughout is on the Anglophone colonies, though we will cover the early Spanish dominance, African migrations, and the LAH 4131 'Atlantic Indians': How Indigenous and African revolution on French St. Domingue. Peoples Shaped Europe & the Americas Col of Arts, Soc Sci and Human, Department of History and Philosophy LAH 4522 The Andes: From the Incas to Today Col of Arts, Soc Sci and Human, Department of History and Philosophy 3 sh (may not be repeated for credit) 3 sh (may not be repeated for credit) The trajectories of European and Native American cultures and societies were enmeshed after 1492. Soldiers, colonists, missionaries, This course follows the development of the Andean region (Venezuela, readers, and consumers were profoundly affected by their exposure to Colombia, Bolivia, Peru, Chile, and Argentina), from the Spanish radically different ways of organizing life, and these effects permeated conquest of the Incan Empire to the fall of the military dictatorships of European culture. This course then takes seriously indigenous men the late 20th century. It examines the formation of the Spanish colonies and women as participants-not merely as objects-in the re-making of and their transition to independent nation-states, though many still intellectual history in the Atlantic world.