The Effect of the Syrian Crisis on Lebanon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NYU/CIC Draft Report

Pathways to Change Baseline Study to Identify Theories of Change on Political Settlements and Confidence Building By Molly Elgin-Cossart, Bruce Jones, and Jane Esberg July 31, 2012 This is one part of a two-part preliminary study. It is designed to excavate, through interviews with development field staff, perspectives and story lines on how international actors (especially development actors) can influence the degree of inclusiveness of political settlements. This is an interim step to a longer-term, more comprehensive study to assess the causal relationship between donor programming and political settlements. The purpose of this initial study is to narrow the field of inquiry by providing ‘theories of change’ that can then be tested. A cognate study, more conceptually oriented, focuses on political settlements (defined below) that follow violence or episodes or imminent threatened violence, to provide an exegesis of the argument that ‘inclusive enough’ settlements matter to stability and thus development in fragile states. That study is designed to help establish a research agenda that could test and refine that proposition. Prepared with support from the UK Department for International Development, the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Carnegie Corporation. 1 Preface ........................................................................................................................... 3 Background: Why an emphasis on inclusive political settlements? ........................... 4 Research approach ....................................................................................................... -

How Lebanese Elites Coopt Protest Discourse: a Social Media Analysis

How Lebanese Elites Coopt Protest Discourse: A Social Media Analysis ."3 Report Policy Alexandra Siegel Founded in 1989, the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies is a Beirut-based independent, non-partisan think tank whose mission is to produce and advocate policies that improve good governance in fields such as oil and gas, economic development, public finance, and decentralization. This report is published in partnership with HIVOS through the Women Empowered for Leadership (WE4L) programme, funded by the Netherlands Foreign Ministry FLOW fund. Copyright© 2021 The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies Designed by Polypod Executed by Dolly Harouny Sadat Tower, Tenth Floor P.O.B 55-215, Leon Street, Ras Beirut, Lebanon T: + 961 1 79 93 01 F: + 961 1 79 93 02 [email protected] www.lcps-lebanon.org How Lebanese Elites Coopt Protest Discourse: A Social Media Analysis Alexandra Siegel Alexandra Siegel is an Assistant Professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, a faculty affiliate of NYU’s Center for Social Media and Politics and Stanford's Immigration Policy Lab, and a nonresident fellow at the Brookings Institution. She received her PhD in Political Science from NYU in 2018. Her research uses social media data, network analysis, and experiments—in addition to more traditional data sources—to study mass and elite political behavior in the Arab World and other comparative contexts. She is a former Junior Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a former CASA Fellow at the American University in Cairo. She holds a Bachelors in International Relations and Arabic from Tufts University. -

Nhdrenglishnew:Layout 1

Lebanon 2008 - 2009 The National Human Development Report toward a citizen’s state Lebanon National Human Development Report toward a citizen's state report summary ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND STUDY TEAMS This project is the result of a collaborative effort between the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR) which composed the steering committee for the report and supported the NHDR project team that directed the project. In addition, an advisory board that brought together public intellectuals, policy makers and academics from the public and private sector was established to guide this very complex process. We extend our deepest gratitude to them all for their cooperation, input and effort during this process. Toward a Citizen's State is the outcome of three years of an elaborate participatory process that included multiple roundtables, focus groups, and brainstorming sessions with over 150 academics, experts and policy makers in different fields as well as a wide range of citizens. To all those who participated in these discussions, debates and especially focus groups we would like to extend our sincerest thanks and appreciation for their contributions toward making this project a success. We hope that our collective effort will indeed bear fruit. The final version of this report is the intellectual product of four core authors who utilized the project outline, the work of participating authors that included background papers commissioned for this report, discussions from focus group meetings, the written inputs of discussants, the debates that took place during the workshops and roundtables and their own knowledge. They were assisted in this process by the NHDR team. -

Le Monde Diplomatique April 1998

Le Monde Diplomatique April 1998 BEHIND THE FACADE OF RECONSTRUCTION The "Lebanese miracle" in danger By Georges Corm "Who is gaining from the reconstruction of Beirut? For nearly six years now, most Lebanese have been urged to rally round a "unifying" theme - the renaissance of their capital - and forget their own vital needs. But the promised miracle has become a mirage. From one end of the country to the other, life is growing increasingly difficult and inequalities ever more glaring. In their quest for an elusive peace in the region, Europe and the United States have chosen to ignore the seriousness of the discontent, continuing instead to dream of "their" Lebanon. The reconstruction of Lebanon has acquired the status of an international myth. The images of desolation, the result of 15 years of war, gave way in 1992 to the good-natured face of Rafiq Hariri, whose main project as prime minister was the reconstruction of Beirut. Seeing models of sky-scrapers, broad avenues and marinas on the television screen, world opinion thought that Lebanon had ended its ordeal and was regaining its place as the Middle East’s financial capital. Since the ideological fashion is to sing the praises of the global economy, the pundits vaunted a Middle East made peaceful by new trade links between Arabs and Israelis. Lebanese reconstruction was immediately seen in the West as a first success along the road to 1 regional realignment after the upheavals of the cold war and the Gulf war. What is the formula for Lebanese-style capitalism without borders or other inhibitions? It is planning large-scale road infrastructures to help growth in regional trade, introducing a 10% income tax ceiling, hoping to privatise what remains of the public services, turning to private capital to rebuild the historic centre of Beirut, using the Build-Operate- Transfer (1) formula in the area of telephony, for example. -

Administrative Decentralization in Lebanon

Administrative Decentralization in Lebanon Practical Steps to Move Forward Michel Akl December 2017 The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in this publication lies entirely with the author and the Democratic Renewal Movement. This paper is the result of a Chatham House process. Have contributed to the content and editing of this publication (in alphabetical order): Rayan Assaf, Issam Bekdache, Melhem Chaoul, Antoine Haddad, Khalil Hajal, Adel Hamieh, Deran Hermandayan, and Ayman Mhanna. P a g e | 2 Table of Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................4 Administrative Decentralization and the Lebanese Parties .........................................5 Main Administrative Decentralization Proposals .............................................................6 The 2014 Sleiman-Baroud Draft Law ...................................................................................7 Reasons for Supporting the Baroud Draft Law ....................................................................... 8 Practical Suggestions towards Administrative Decentralization .............................10 On the Municipal Level.............................................................................................................. 10 Adoption of the Baroud Draft Law ......................................................................................... -

Public Transcript of the Hearing Held on 20 November 2014 in the Case

20141120_STL-11-01_T_T96_OFF_PUB_EN 1/46 PUBLIC Official Transcript Procedural Matters (Open Session) Page 1 1 Special Tribunal for Lebanon 2 In the case of The Prosecutor v. Ayyash, Badreddine, Merhi, 3 Oneissi, and Sabra 4 STL-11-01 5 Presiding Judge David Re, Judge Janet Nosworthy, Judge Walid Akoum, and 6 Judge Nicola Lettieri - [Trial Chamber] 7 Thursday, 20 November 2014 - [Trial Hearing] 8 [Open Session] 9 --- Upon commencing at 10.09 a.m. 10 [The witness takes the stand] 11 THE REGISTRAR: The Special Tribunal for Lebanon is sitting in an 12 open session case of the Prosecutor versus Ayyash, Badreddine, Merhi, 13 Oneissi, and Sabra, case number STL-11-01. 14 PRESIDING JUDGE RE: Good morning. We are sitting to continue 15 with the evidence of Mr. Hamade. 16 Good morning to you -- 17 THE WITNESS: Good morning, Your Honour. 18 PRESIDING JUDGE RE: -- Mr. Hamade. I trust that you are well 19 refreshed and ready to continue with your evidence. 20 THE WITNESS: Yes, thank you, Your Honour. 21 PRESIDING JUDGE RE: All right. Before we get to your evidence, 22 I'll just note the appearances for the day. 23 And for the Prosecution we have Mr. Cameron and Ms. Bari. For 24 the Legal Representatives of the Victims, Mr. Haynes and 25 Ms. Abdelsater-Abusamra. For Mr. Ayyash Mr. Hannis is here, Mr. Edwards Thursday, 20 November 2014 STL-11-01 Interpretation serves to facilitate communication. Only the original speech is authentic. 20141120_STL-11-01_T_T96_OFF_PUB_EN 2/46 PUBLIC Official Transcript Witness: Marwan Hamade –PRH038 (Resumed) (Open Session) Page 2 Examination by Mr. -

Social Classes and Political Power in Lebanon

Social Classes This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung - Middle East Office. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and can therefore in no way be taken to reflect the opinion of the Foundation. and Political Power in Lebanon Fawwaz Traboulsi Social Classes and Political Power in Lebanon Fawwaz Traboulsi This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung - Middle East Office. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and can therefore in no way be taken to reflect the opinion of the Foundation. Content 1- Methodology ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 2- From Liberalism to Neoliberalism .................................................................................................................................... 23 3- The Oligarchy ................................................................................................................................................................................. 30 4- The Middle Classes............................................................................................................................... ..................................... 44 5- The Working Classes ................................................................................................................................................................. -

50.Book.En.Pdf

Horizons 2017 THE SYKES PICOT AGREEMENT LIMITS OF AMBITIONS Le Sérail - Bikfaya This book was published wiTh The supporT of FIRST NATIONAL BANK S.A.L. Designed by Saad Kiwan PrinTed in BeiruT (LEBANON) by: ISBN: 978-9953-0-4399-9 Chemaly & Chemaly © Maison du FuTur, 2017 13 Foreword, 153 The Two-State President Amine Gemayel Solution and Beyond Perceptions for the Future 15 Religious Values of the Palestinian cause in Politics and possible settlements The Past, Present and Future of Christian Democratic Parties 209 Homage to 15 Bernhard Vogel Walid Akl 25 Radwan el-Sayed 213 Tolerance: A Vision 31 Crossing Towards and Doctrine Embraced the Rule of Law by Imam el-Sader 213 Rabab el-Sadr 53 Oil and Gas 216 Ahmad el-Ghez 57 Media Efficiency 219 External Actors in under Regional and Syria II International Variables Assessing the Influence and Interests of Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar 69 The Limits of and Israel Ambitions External Interventions 241 New Electoral Law: and the States System in the Arab Middle East Towards what Lebanon Challenges, Alignments, Expectations 261 Exhibition of Suzani Textiles 121 Lebanon and the Syrian Refugees Human Dignity, Counter-Extremism and Safe Return at Stake CONTENTS 11 FOREWORD 2017 was an extraordinary year with the various developments it has wit- nessed in the course of the earth-shattering conflicts that have engulfed the Mina region in the wake of the so-called Arab Spring starting early 2011. Such developments include the collapse of ISIS in Iraq and Syria, the Saudi Iranian polarization and its drastic fallout on the region, the gains achieved by the pro-Syrian regime alliance at the expense of the political and military opposition, which endangers ongoing efforts to reach a long-term polit- ical settlement for the Syrian crisis. -

Toward a Citizen's State

Lebanon 2008 - 2009 The National Human Development Report toward a citizen’s state Lebanon National Human Development Report toward a citizen's state ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND STUDY TEAMS This project is the result of a collaborative effort between the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR) which composed the steering committee for the report and supported the NHDR project team that directed the project. In addition, an advisory board that brought together public intellectuals, policy makers and academics from the public and private sector was established to guide this very complex process. We extend our deepest gratitude to them all for their cooperation, input and effort during this process. Toward a Citizen's State is the outcome of three years of an elaborate participatory process that included multiple roundtables, focus groups, and brainstorming sessions with over 150 academics, experts and policy makers in different fields as well as a wide range of citizens. To all those who participated in these discussions, debates and especially focus groups we would like to extend our sincerest thanks and appreciation for their contributions toward making this project a success. We hope that our collective effort will indeed bear fruit. The final version of this report is the intellectual product of four core authors who utilized the project outline, the work of participating authors that included background papers commissioned for this report, discussions from focus group meetings, the written inputs of discussants, the debates that took place during the workshops and roundtables and their own knowledge. They were assisted in this process by the NHDR team. -

MPC – Migration Policy Centre

MPC – MIGRATION POLICY CENTRE Co-financed by the European Union Syrian Refugees in Lebanon: the Humanitarian Approach under Political Divisions Hala Naufal MPC Research Report 2012/13 © 2012. All rights reserved. No part of this paper may be distributed, quoted or reproduced in any form without permission from the MPC. EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES MIGRATION POLICY CENTRE (MPC) Syrian Refugees in Lebanon: the Humanitarian Approach under Political Divisions HALA NAUFAL MIGRATION POLICY CENTRE (MPC) RESEARCH REPORT, MPC RESEARCH REPORT 2012/13 BADIA FIESOLANA, SAN DOMENICO DI FIESOLE (FI) © 2012, European University Institute Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. Requests should be addressed to [email protected] If cited or quoted, reference should be made as follows: Hala Naufal, Syrian Refugees in Lebanon: the Humanitarian Approach under Political Divisions, MPC RR 2012/13, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, San Domenico di Fiesole (FI): European University Institute, 2012. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED IN THIS PUBLICATION CANNOT IN ANY CIRCUMSTANCES BE REGARDED AS THE OFFICIAL POSITION OF THE EUROPEAN UNION The Migration Policy Centre (MPC) Mission statement The Migration Policy Centre at the European University Institute, Florence, conducts advanced research on global migration to serve migration governance needs at European level, from developing, implementing and monitoring migration-related policies to assessing their impact on the wider economy and society. Rationale Migration represents both an opportunity and a challenge. -

CEDRE Conference for Years, Lebanon Has Been Plagued With

CEDRE Conference Geopolitical Context and its Implication on the Domestic Front Opportunities and Realization Potentials Maison du Futur, Sérail Bikfaya Friday, 21 September, 2018 For years, Lebanon has been plagued with vulnerabilities and mounting challenges, bearing the full force of regional tensions, particularly the neighboring Syrian war; these conflicts have negatively affected its economy, development, infrastructure and social fabric, along with structural problems that have hampered the long-term path of economic recovery and development. France hosted the "International Conference to Support Lebanon through Development and Reform" (CEDRE) on 6 April 2018, under the auspices of French President Emmanuel Macron and Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri, and the participation of 50 countries, foundations and representatives of the private sector and civil society. During this conference, viewed as an expression of the international community's commitment to the stability, security and sovereignty of Lebanon, the Lebanese government presented its Capital Investment Plan (CIP) based on four pillars: Raising the level of investment in the public and private sectors, ensuring economic and financial stability through fiscal adjustment, commitments to reforms in various sectors, including countering corruption, modernizing the public sector and the fiscal management sector, and develop a strategy for multi-sectoral production and export potential. In line with the efforts Maison du Futur (MdF) has been deploying to keep pace with what would advance the political, economic and social conditions in Lebanon, MdF in cooperation with the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung and Levant Institute for Strategic and Economic Affairs, held at its headquarters in Saraya Bikfaya on Friday, 21 September 2018, a round table to discuss two policy papers, the first entitled “The Paris Conference IV: Opportunities and Implementation Potentials”, prepared by Dr. -

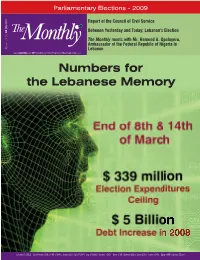

Numbers for the Lebanese Memory

Parliamentary Elections - 2009 Report of the Council of Civil Service May 2009 | Between Yesterday and Today: Lebanon’s Election 82 The Monthly meets with Mr. Hameed A. Opeloyeru, Ambassador of the Federal Republic of Nigeria in issue number Lebanon www.iimonthly.com • Published by Information International sal Numbers for the Lebanese Memory Lebanon 5,000LL | Saudi Arabia 15SR | UAE 15DHR | Jordan 2JD| Syria 75SYP | Iraq 3,500IQD | Kuwait 1.5KD | Qatar 15QR | Bahrain 2BD | Oman 2OR | Yemen 15YRI | Egypt 10EP | Europe 5Euros 2 iNDEX PAGE PAGE 4 Parliamentary Elections - 2009 Number of Candidates 702, Ceiling of Expenditures LBP 508,238,006,000 ($339 Million) LEADER 32 International Media Obama & Turkey 14 The Year 2008 in Review 34 Diabetes by Dr. Hanna Saadah 16 Arab and Foreign Companies in Lebanon - July - December 2008 35 The Credit of Relocating Man’s Position in the Universe? 17 Vehicle license plates and mobile by Antoine Boutros numbers sold at high prices 36 The Syndicate of Taxi Drivers and 18 Report of the Council of Civil Public Transport Vehicle Owners Service in Beirut 20 Between Yesterday and Today 38 Schools in Lebanon 21 Beggary 40 Business and Computer University College – BCU 22 Four Lebanese soldiers killed (Hawai University) 24 Myth #23 42 The Monthly meets 10,452 km2, 10,200 km2, or 10, with Mr. Hameed 415 km2? A. Opeloyeru, Ambassador of the Federal Republic of 25 General Aoun and Syria Nigeria in Lebanon 26 Domani Families 44 Fashion in Lebanon 27 Real Estate Index: March 2009 46 Khyara & Lala 28 Consumer Price Index: March 48 Lebanese Banks In Syria: What 2009 Role Do They Play? 30 The Mountain, a Truth that has no 50 Stats around the World Mercy by Paul Indari 50 Airport traffic- March 2009 31 Walt Disney Stories “Dumbo” and “The Lady and the Tramp” issue 82 - published by Information International s.a.l.