Intermediary Metabolism: an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Insight Into Role of Phosphoketolase Pathway in Synechocystis Sp

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN A new insight into role of phosphoketolase pathway in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 Anushree Bachhar & Jiri Jablonsky* Phosphoketolase (PKET) pathway is predominant in cyanobacteria (around 98%) but current opinion is that it is virtually inactive under autotrophic ambient CO2 condition (AC-auto). This creates an evolutionary paradox due to the existence of PKET pathway in obligatory photoautotrophs. We aim to answer the paradox with the aid of bioinformatic analysis along with metabolic, transcriptomic, fuxomic and mutant data integrated into a multi-level kinetic model. We discussed the problems linked to neglected isozyme, pket2 (sll0529) and inconsistencies towards the explanation of residual fux via PKET pathway in the case of silenced pket1 (slr0453) in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Our in silico analysis showed: (1) 17% fux reduction via RuBisCO for Δpket1 under AC-auto, (2) 11.2–14.3% growth decrease for Δpket2 in turbulent AC-auto, and (3) fux via PKET pathway reaching up to 252% of the fux via phosphoglycerate mutase under AC-auto. All results imply that PKET pathway plays a crucial role under AC-auto by mitigating the decarboxylation occurring in OPP pathway and conversion of pyruvate to acetyl CoA linked to EMP glycolysis under the carbon scarce environment. Finally, our model predicted that PKETs have low afnity to S7P as a substrate. Metabolic engineering of cyanobacteria provides many options for producing valuable compounds, e.g., acetone from Synechococcus elongatus PCC 79421 and butanol from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 68032. However, certain metabolites or overproduction of intermediates can be lethal. Tere is also a possibility that required mutation(s) might be unstable or the target bacterium may even be able to maintain the fux distribution for optimal growth balance due to redundancies in the metabolic network, such as alternative pathways. -

Sterile Spikelets Assimilate Carbon in Sorghum and Related Grasses

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/396473; this version posted January 5, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. This article is a US Government work. It is not subject to copyright under 17 USC 105 and is also made available for use under a CC0 license. 1 Sterile spikelets assimilate carbon in sorghum and related grasses Taylor AuBuchon-Elder1,a, Viktoriya Coneva1,a,d, David M. Goad a,b, Doug K. Allen2,a,c,e, and Elizabeth A. Kellogg2,a,e aDonald Danforth Plant Science Center, St. Louis, Missouri, 63132 USA bDepartment of Biology, Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri, 63130 USA cUSDA-ARS, St. Louis, Missouri, 63132 USA 1These authors contributed equally to this work. 2These authors contributed equally to this work. dCurrent address: Kenyon College, Gambier, OH 43022 eAddress correspondence to: [email protected]; [email protected] ORCID IDs: 0000-0002-0640-5135 (V.C.); 0000-0001-8658-6660 (D.M.G.); 0000-0001-8599- 8946 (D.K.A.); 0000-0003-1671-7447 (E.A.K.) Short title: Carbon assimilation in sorghum spikelets The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article is Elizabeth A. Kellogg ([email protected]). bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/396473; this version posted January 5, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. This article is a US Government work. It is not subject to copyright under 17 USC 105 and is also made available for use under a CC0 license. -

RESPIRATION Pentose Phosphate Pathway Or Hexose Monophosphate Pathway

RESPIRATION Pentose Phosphate Pathway or Hexose Monophosphate Pathway Pentose phosphate pathway or hexose monophosphate pathway (HMP pathway) is the other common pathway to break down glucose to pyruvate and operates in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. This pathway produces NADPH, which carries chemical energy in the form of reducing power and is used almost universally as the reductant in anabolic (energy utilization) pathways (e.g., fatty acid biosynthesis, cholesterol biosynthesis, nucleotide biosynthesis) and detoxification pathways (e.g., reduction of oxidized glutathione, cytochrome P450 monooxygenases). Also, the pentose phosphate pathway generates pentose sugar ribose and its derivatives, which are necessary for the biosynthesis of nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) as well as ATP, NADH, FAD, and coenzyme A. In this way, though the pentose phosphate pathway may be a source of energy in many microorganisms, it is more often of greater importance in various biosynthetic pathways. Pentose phosphate pathway consists of two phases: the oxidative phase and the non-oxidative phase. Oxidative Phase: The oxidative phase of the pentose phosphate pathway initiates with the conversion of glucose 6- phosphate to 6-Phosphogluconate. NADP+ is the electron acceptor yielding NADPH during this reaction. 6-Phosphogluconate, a six-carbon sugar, is then oxidativelydecarboxylated to yield ribulose 5-phosphate, a five-carbon sugar. NADP+ is again the electron acceptor yielding NADPH. In the final step of oxidative phase, there is isomerisation of ribulose 5-phosphatc to ribose 5- phosphate by phosphopentose isomerase and the conversion of ribulose 5-phosphate into its epimerxylulose 5-phosphate by phosphopentose epimerase for the transketolase reaction in non- oxidative phase. -

CDH12 Cadherin 12, Type 2 N-Cadherin 2 RPL5 Ribosomal

5 6 6 5 . 4 2 1 1 1 2 4 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R B , B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B , 9 , , , , 4 , , 3 0 , , , , , , , , 6 2 , , 5 , 0 8 6 4 , 7 5 7 0 2 8 9 1 3 3 3 1 1 7 5 0 4 1 4 0 7 1 0 2 0 6 7 8 0 2 5 7 8 0 3 8 5 4 9 0 1 0 8 8 3 5 6 7 4 7 9 5 2 1 1 8 2 2 1 7 9 6 2 1 7 1 1 0 4 5 3 5 8 9 1 0 0 4 2 5 0 8 1 4 1 6 9 0 0 6 3 6 9 1 0 9 0 3 8 1 3 5 6 3 6 0 4 2 6 1 0 1 2 1 9 9 7 9 5 7 1 5 8 9 8 8 2 1 9 9 1 1 1 9 6 9 8 9 7 8 4 5 8 8 6 4 8 1 1 2 8 6 2 7 9 8 3 5 4 3 2 1 7 9 5 3 1 3 2 1 2 9 5 1 1 1 1 1 1 5 9 5 3 2 6 3 4 1 3 1 1 4 1 4 1 7 1 3 4 3 2 7 6 4 2 7 2 1 2 1 5 1 6 3 5 6 1 3 6 4 7 1 6 5 1 1 4 1 6 1 7 6 4 7 e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m -

HOXB6 Homeo Box B6 HOXB5 Homeo Box B5 WNT5A Wingless-Type

5 6 6 5 . 4 2 1 1 1 2 4 6 4 3 2 9 9 7 0 5 7 5 8 6 4 0 8 2 3 1 8 3 7 1 0 0 4 0 2 5 0 8 7 5 4 1 1 0 3 6 0 4 8 3 7 4 7 6 9 6 7 1 5 0 8 1 4 1 1 7 1 0 0 4 2 0 8 1 1 1 2 5 3 5 0 7 2 6 9 1 2 1 8 3 5 2 9 8 0 6 0 9 5 1 9 9 2 1 1 6 0 2 3 0 3 6 9 1 6 5 5 7 1 1 2 1 1 7 5 4 6 6 4 1 1 2 8 4 7 1 6 2 7 7 5 4 3 2 4 3 6 9 4 1 7 1 3 4 1 2 1 3 1 1 4 7 3 1 1 1 1 5 3 2 6 1 5 1 3 5 4 5 2 3 1 1 6 1 7 3 2 5 4 3 1 6 1 5 3 1 7 6 5 1 1 1 4 6 1 6 2 7 2 1 2 e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S HOXB6 homeo box B6 HOXB5 homeo box B5 WNT5A wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 5A WNT5A wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 5A FKBP11 FK506 binding protein 11, 19 kDa EPOR erythropoietin receptor SLC5A6 solute carrier family 5 sodium-dependent vitamin transporter, member 6 SLC5A6 solute carrier family 5 sodium-dependent vitamin transporter, member 6 RAD52 RAD52 homolog S. -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Chapter 23 Gluconeogenesis Gluconeogenesis, Con't

BCH 4054 Spring 2001 Chapter 23 Lecture Notes Slide 1 Chapter 23 Gluconeogenesis Glycogen Metabolism Pentose Phosphate Pathway Slide 2 Gluconeogenesis • Humans use about 160 g of glucose per day, about 75% for the brain. • Body fluids and glycogen stores supply only a little over a day’s supply. • In absence of dietary carbohydrate, the needed glucose must be made from non- carbohydrate precursors. • That process is called gluconeogenesis. Slide 3 Gluconeogenesis, con’t. • Brain and muscle consume most of the glucose. • Liver and kidney are the main sites of gluconeogenesis. • Substrates include pyruvate, lactate, glycerol, most amino acids, and all TCA intermediates. • Fatty acids cannot be converted to glucose in animals. • (They can in plants because of the glyoxalate cycle.) Chapter 23, page 1 Slide 4 Remember it is necessary for the pathways to differ in some respects, Gluconeogenesis, con’t. so that the overall DG can be negative in each direction. Usually • Substrates include anything that can be converted the steps with large negative DG of to phosphoenolpyruvate . one pathway are replaced in the • Many of the reactions are the same as those in reverse pathway with reactions that glycolysis. have a large negative DG in the • All glycolytic reactions which are near equilibrium can opposite direction. operate in both directions. • The three glycolytic reactions far from equilibrium (large -DG) must be bypassed. • A side by side comparison is shown in Fig 23.1. Slide 5 Unique Reactions of Gluconeogenesis • Recall that pyruvate kinase, though named in reverse, is not reversible and has a DG of –23 kJ/mol. -

(10) Patent No.: US 8119385 B2

US008119385B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,119,385 B2 Mathur et al. (45) Date of Patent: Feb. 21, 2012 (54) NUCLEICACIDS AND PROTEINS AND (52) U.S. Cl. ........................................ 435/212:530/350 METHODS FOR MAKING AND USING THEMI (58) Field of Classification Search ........................ None (75) Inventors: Eric J. Mathur, San Diego, CA (US); See application file for complete search history. Cathy Chang, San Diego, CA (US) (56) References Cited (73) Assignee: BP Corporation North America Inc., Houston, TX (US) OTHER PUBLICATIONS c Mount, Bioinformatics, Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Har (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this bor New York, 2001, pp. 382-393.* patent is extended or adjusted under 35 Spencer et al., “Whole-Genome Sequence Variation among Multiple U.S.C. 154(b) by 689 days. Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa” J. Bacteriol. (2003) 185: 1316 1325. (21) Appl. No.: 11/817,403 Database Sequence GenBank Accession No. BZ569932 Dec. 17. 1-1. 2002. (22) PCT Fled: Mar. 3, 2006 Omiecinski et al., “Epoxide Hydrolase-Polymorphism and role in (86). PCT No.: PCT/US2OO6/OOT642 toxicology” Toxicol. Lett. (2000) 1.12: 365-370. S371 (c)(1), * cited by examiner (2), (4) Date: May 7, 2008 Primary Examiner — James Martinell (87) PCT Pub. No.: WO2006/096527 (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm — Kalim S. Fuzail PCT Pub. Date: Sep. 14, 2006 (57) ABSTRACT (65) Prior Publication Data The invention provides polypeptides, including enzymes, structural proteins and binding proteins, polynucleotides US 201O/OO11456A1 Jan. 14, 2010 encoding these polypeptides, and methods of making and using these polynucleotides and polypeptides. -

Clostridium Difficile Exploits a Host Metabolite Produced During Toxin-Mediated Infection

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.14.426744; this version posted January 15, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Clostridium difficile exploits a host metabolite produced during toxin-mediated infection 2 3 Kali M. Pruss and Justin L. Sonnenburg* 4 5 Department of Microbiology & Immunology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford 6 CA, USA 94305 7 *Corresponding author address: [email protected] 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.14.426744; this version posted January 15, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 23 Several enteric pathogens can gain specific metabolic advantages over other members of 24 the microbiota by inducing host pathology and inflammation. The pathogen Clostridium 25 difficile (Cd) is responsible for a toxin-mediated colitis that causes 15,000 deaths in the U.S. 26 yearly1, yet the molecular mechanisms by which Cd benefits from toxin-induced colitis 27 remain understudied. Up to 21% of healthy adults are asymptomatic carriers of toxigenic 28 Cd2, indicating that Cd can persist as part of a healthy microbiota; antibiotic-induced 29 perturbation of the gut ecosystem is associated with transition to toxin-mediated disease. -

Deliverable 1.5 Model of Plant Photosynthesis

PROJECT ACRONYM: FutureAgriculture PROJECT TITLE: Transforming the future of agriculture through synthetic photorespiration Deliverable 1.5 Model of plant photosynthesis TOPIC H2020-FETOPEN-2014-2015-RIA GA 686330 Arren Bar-Even CONTACT PERSON [email protected] NATURE Report (R) DISSEMINATION LEVEL PU DUE DATE 31/12/2018 ACTUAL DELIVERED DATE 14/12/2018 AUTHOR Christian Edlich-Muth This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 686330. Table of Revisions REVISION NUMBER DATE WORK PERFORMED CONTRIBUTOR(S) 1 05/12/2018 Document preparation MPIMP 2 06/12/2018 Formatting IN 3 13/12/2018 Revision Consortium D1.5 – Model of plant photosynthesis Page 2 03/04/2018 Contents 1ExecutiveSummary 5 2Cooperationbetweenparticipants 6 3 Core report 7 3.1 Theory............................................. 7 3.1.1 Pathways . 7 3.1.2 The stoichiometric consumer model of photosynthesis . 9 3.1.3 Stoichiometric-kineticmodel. 13 3.1.4 Physicochemicalparameters. 24 3.2 Results............................................. 27 3.2.1 Parametersandvariables .............................. 27 3.2.2 Rubiscokinetics ................................... 28 3.2.3 Limitation by light . 30 3.2.4 LimitationbyenzymeactivitiesotherthanRubisco. 31 3.2.5 Limitation by a Calvin cycle enzyme . 31 3.2.6 Limitationbyaphotorespiratoryenzyme . 34 3.2.7 Limitationbyaphotorespirationcarboxylase . 35 4 Conclusions 37 D1.5Modelofplantphotosynthesis Page3 03/04/2018 Table of Charts 1 Bypass coefficients ........................................ 11 2 Flux distribtion of the Calvin cycle and photorespiratory bypasses . 20 3 Kinetic constants of Rubisco and carbon dioxide diffusion .................. 28 4 Calvin cycle enzyme total activities . 33 Table of Figures 1 Energy requirements of native photorespiration and the Calvin cycle . -

NRF2 and the Ambiguous Consequences of Its Activation During Initiation and the Subsequent Stages of Tumourigenesis

cancers Review NRF2 and the Ambiguous Consequences of Its Activation during Initiation and the Subsequent Stages of Tumourigenesis Holly Robertson 1,2, Albena T. Dinkova-Kostova 1 and John D. Hayes 1,* 1 Jacqui Wood Cancer Centre, Division of Cellular Medicine, Ninewells Hospital and Medical School, University of Dundee, Dundee DD1 9SY, Scotland, UK; [email protected] (H.R.); [email protected] (A.T.D.-K.) 2 Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Genome Campus, Cambridge CB10 1SA, UK * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-(0)-1382-383182 Received: 30 October 2020; Accepted: 27 November 2020; Published: 2 December 2020 Simple Summary: Transcription factor NRF2 controls expression of antioxidant and detoxification genes. Normally, the activity of NRF2 is tightly controlled in the cell, and is continuously adjusted to ensure that cells are protected against endogenous chemicals and environmental agents that perturb the intracellular antioxidant/pro-oxidant balance (i.e., redox) that must be maintained for them to grow and survive in an appropriate manner. This tight control of NRF2 is achieved by a repressor protein called KEAP1 that perpetually targets NRF2 protein for degradation under normal conditions, but is unable to do so when challenged with oxidants or thiol-reactive chemicals. In the context of cancer, it is well known that drugs that stimulate short-term and reversible activation of NRF2 can provide protection for a limited period against exposure to chemicals that cause cancer. However, it is also becoming widely recognised that permanent hyper-activation of NRF2 resulting from somatic mutations in the gene that encodes NRF2, or in genes associated with its degradation, is frequently observed in certain cancers and associated with poor outcome. -

Pentose Phosphate Pathway

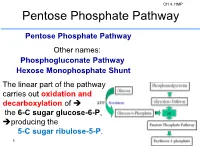

CH 4. HMP Pentose Phosphate Pathway Pentose Phosphate Pathway Other names: Phosphogluconate Pathway Hexose Monophosphate Shunt The linear part of the pathway carries out oxidation and decarboxylation of the 6-C sugar glucose-6-P, producing the 5-C sugar ribulose-5-P. 1 2 CH 4. HMP Glucose metabolism via the oxidative pentose phosphate pathways and relationship with glycolysis. Principal cellular functions of the pathways are indicated, and roles of NADPH included. G6PDH, glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase; PGDH, 6- 3 phosphogluconate dehydrogenase; RPE, ribulose-5-phosphate 3-epimerase; RPI, ribose 5-phosphate isomerase; TKL, transketolase. CH 4. HMP Hexose Monophosphate Pathway CH 4. HMP 4 Hexose Monophosphate Pathway It consists of two irreversible oxidative reactions, followed by a series of reversible sugar-phosphate interconversions No ATP is directly consumed or produced in the cycle. Carbon 1 of glucose 6-phosphate is released as CO2, and two NADPH are produced for each glucose 6-phosphate entering the oxidative part of the pathway. 5 CH 4. HMP The rate and direction of the reactions at any given time are determined by the supply of and demand for intermediates in the cycle. The HMP occurs in the cytosol of the cell. The pathway provides a major portion of the cell's NADPH, which functions as a biochemical reductant. The HMP also produces ribose-phosphate, required for biosynthesis of nucleotides, 6 CH 4. HMP for each molecule of glucose 6-phosphate oxidized. 1. Dehydrogenation of glucose 6-phosphate 2. Hydrolysis of 6- phosphogluconolactone and formation of ribulose 5- phosphate. The oxidative portion of the HMP leads to the formation of -two molecules of NADPH -CO2, and -ribulose 5-phosphate, 7 CH 4.