539814-00713.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act Implicates the First Amendment in Universal City Studios, Inc. V. Reimerdes

The Freedom to Link?: The Digital Millennium Copyright Act Implicates the First Amendment in Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Reimerdes David A. Petteys* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. IN TRO D U CTIO N .............................................................. 288 II. THE WEB, FREE EXPRESSION, COPYRIGHT, AND THE D M C A .............................................................................. 290 III. THE CASE: UNIVERSAL CITY STUDIOS, INC. V. R EIMERD ES ...................................................................... 293 A . Factual Background ................................................... 294 B . Findings of F act ......................................................... 297 C. The Court's Statutory and Constitutional Analysis ..... 298 1. Statutory A nalysis ................................................ 299 a. Section 1201(a)(1) ............................................ 299 b. Linking to Other Sites with DeCSS .................. 302 2. First Amendment Challenges ................................ 304 a. DMCA Prohibition Against Posting DeCSS .... 305 b. Prior R estraint ................................................ 307 c. The Prohibition on Linking ............................. 309 3. T he R em edy ........................................................ 312 IV . A N A LYSIS ......................................................................... 314 A. The Prohibition Against Posting DeCSS ..................... 314 1. F air U se ............................................................... 314 2. First Amendment -

Handout 5 Summary of This Handout: Stream Ciphers — RC4 — Linear Feedback Shift Registers — CSS — A5/1

06-20008 Cryptography The University of Birmingham Autumn Semester 2009 School of Computer Science Volker Sorge 30 October, 2009 Handout 5 Summary of this handout: Stream Ciphers — RC4 — Linear Feedback Shift Registers — CSS — A5/1 II.2 Stream Ciphers A stream cipher is a symmetric cipher that encrypts the plaintext units one at a time and that varies the transformation of successive units during the encryption. In practise, the units are typically single bits or bytes. In contrast to a block cipher, which encrypts one block and then starts over again, a stream cipher encrypts plaintext streams continuously and therefore needs to maintain an internal state in order to avoid obvious duplication of encryptions. The main difference between stream ciphers and block ciphers is that stream ciphers have to maintain an internal state, while block ciphers do not. Recall that we have already seen how block ciphers avoid duplication and can also be transformed into stream ciphers via modes of operation. Basic stream ciphers are similar to the OFB and CTR modes for block ciphers in that they produce a continuous keystream, which is used to encipher the plaintext. However, modern stream ciphers are computationally far more efficient and easier to implement in both hard- and software than block ciphers and are therefore preferred in applications where speed really matters, such as in real-time audio and video encryption. Before we look at the technical details how stream ciphers work, we recall the One Time Pad, which we have briefly discussed in Handout 1. The One Time Pad is essentially an unbreakable cipher that depends on the fact that the key 1. -

Information Disclosure Mechanism for Technological Protection Measures in China

Journal of Intellectual Property Rights Vol 17, November 2012, pp 532-538 Information Disclosure Mechanism for Technological Protection Measures in China Lili Zhao† Center for China Information Security Law, Xi’an Jiao tong University, Shaanxi Xi’an, P R China 710 049 Received 12 February 2012, revised 21 May 2012 With increasing cases of digital works being copied and pirated, technological protection measures have been greatly favoured by copyright owners for protecting the intellectual property in their digital works, while ensuring that these works can be used and disseminated. However, when any copyright owner or supplier fails to disclose the information of technological protection measures appropriately or effectively, damages such as privacy violations, security breaches and unfair competition may be caused to the public. Therefore, it is necessary to establish an information disclosure mechanism for technological protection measures, make the labeling obligation with regard to technological protection measures by copyright owners apparent and warning to security risks obligatory by legislation; effectively guarding against information security threats from the technological protection measures. Keywords: Technological protection measures, TPM, information disclosure, label and warning The advance of digital technologies make many information security, it is necessary to integrate such acts things become possible, including the copy and in a standardized, normalized and legal manner. dissemination of commercially valuable digital works Therefore, to further prevent copyright owners from through global digital network. Particularly, among using insecure or untested software, protect information the copyright owners of entertainment industry, security and prohibit the abuse of TPMs; disclosure technological protection measures (TPMs) have been obligations should be established for the right holders of regarded as a necessary creation to help digital works TPMs in the form of legislation. -

Digital Rights Management and the Process of Fair Use Timothy K

University of Cincinnati College of Law University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications Faculty Articles and Other Publications Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2006 Digital Rights Management and the Process of Fair Use Timothy K. Armstrong University of Cincinnati College of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.uc.edu/fac_pubs Part of the Intellectual Property Commons Recommended Citation Armstrong, Timothy K., "Digital Rights Management and the Process of Fair Use" (2006). Faculty Articles and Other Publications. Paper 146. http://scholarship.law.uc.edu/fac_pubs/146 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Articles and Other Publications by an authorized administrator of University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harvard Journal ofLaw & Technology Volume 20, Number 1 Fall 2006 DIGITAL RIGHTS MANAGEMENT AND THE PROCESS OF FAIR USE Timothy K. Armstrong* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION: LEGAL AND TECHNOLOGICAL PROTECTIONS FOR FAIR USE OF COPYRIGHTED WORKS ........................................ 50 II. COPYRIGHT LAW AND/OR DIGITAL RIGHTS MANAGEMENT .......... 56 A. Traditional Copyright: The Normative Baseline ........................ 56 B. Contemporary Copyright: DRM as a "Speedbump" to Slow Mass Infringement .......................................................... -

The Fuzzy Software Patent Debate Rages On

OPINION The Fuzzy Software Patent Debate Rages On By Heather J. Meeker LinuxInsider 02/23/05 5:00 AM PT Once upon a time, we intellectual property lawyers got to live peacefully in our ivory towers. Now it seems that intellectual property policy issues have become fraught with partisan rhetoric. Most open-source promoters are against software patents. Most corporate spokesmen side with patents, period, whether they cover software or not. But it is worth looking beyond the rhetoric. The European Commission recently tolled the death knell for the EU Software Patent Directive, or more precisely, the "Directive on the Patentability of Computer- Implemented Inventions." Like most Americans, I am fairly clueless about the EU political process, and I wouldn't presume to write about exactly how it was killed. But the decision may have been swayed by an eleventh-hour public relations pitch against the directive by open-source spokesmen from the United States. On that aspect, I will add my two cents. A delegation of open-source leaders, led by Linus Torvalds, published an "Appeal" at softwarepatents.com, calling software patents "dangerous to the economy at large, and particularly to the European economy." Look Beyond the Rhetoric Leaders of the open-source software movement have long been harsh critics of software patents. The GPL [license] itself says, "any free program is threatened constantly by software patents." The appeal contends that copyright provides adequate protection for the creations of software authors. The Appeal advocated reliance on copyright law, rather than patent law, for the protection of software. Not long afterward, in late January, the European Parliament's Legal Affairs Committee recommended scrapping the pending directive, extending the debate until at least the end From www.linuxinsider.com/story/40676.html 1 April 2011 of the year. -

How Marvel and Sony Sparked Public

Cleveland State Law Review Volume 69 Issue 4 Article 8 6-18-2021 America's Broken Copyright Law: How Marvel and Sony Sparked Public Debate Surrounding the United States' "Broken" Copyright Law and How Congress Can Prevent a Copyright Small Claims Court from Making it Worse Izaak Horstemeier-Zrnich Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Izaak Horstemeier-Zrnich, America's Broken Copyright Law: How Marvel and Sony Sparked Public Debate Surrounding the United States' "Broken" Copyright Law and How Congress Can Prevent a Copyright Small Claims Court from Making it Worse, 69 Clev. St. L. Rev. 927 (2021) available at https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev/vol69/iss4/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cleveland State Law Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMERICA’S BROKEN COPYRIGHT LAW: HOW MARVEL AND SONY SPARKED PUBLIC DEBATE SURROUNDING THE UNITED STATES’ “BROKEN” COPYRIGHT LAW AND HOW CONGRESS CAN PREVENT A COPYRIGHT SMALL CLAIMS COURT FROM MAKING IT WORSE IZAAK HORSTEMEIER-ZRNICH* ABSTRACT Following failed discussions between Marvel and Sony regarding the use of Spider-Man in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, comic fans were left curious as to how Spider-Man could remain outside of the public domain after decades of the character’s existence. -

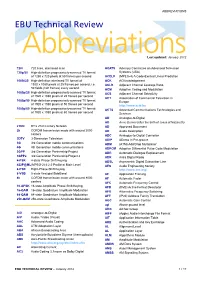

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review AbbreviationsLast updated: January 2012 720i 720 lines, interlaced scan ACATS Advisory Committee on Advanced Television 720p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Systems (USA) of 1280 x 720 pixels at 50 frames per second ACELP (MPEG-4) A Code-Excited Linear Prediction 1080i/25 High-definition interlaced TV format of ACK ACKnowledgement 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second, i.e. ACLR Adjacent Channel Leakage Ratio 50 fields (half frames) every second ACM Adaptive Coding and Modulation 1080p/25 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACS Adjacent Channel Selectivity of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second ACT Association of Commercial Television in 1080p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Europe of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 50 frames per second http://www.acte.be 1080p/60 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACTS Advanced Communications Technologies and of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 60 frames per second Services AD Analogue-to-Digital AD Anno Domini (after the birth of Jesus of Nazareth) 21CN BT’s 21st Century Network AD Approved Document 2k COFDM transmission mode with around 2000 AD Audio Description carriers ADC Analogue-to-Digital Converter 3DTV 3-Dimension Television ADIP ADress In Pre-groove 3G 3rd Generation mobile communications ADM (ATM) Add/Drop Multiplexer 4G 4th Generation mobile communications ADPCM Adaptive Differential Pulse Code Modulation 3GPP 3rd Generation Partnership Project ADR Automatic Dialogue Replacement 3GPP2 3rd Generation Partnership -

Intellectual Property Part 2 Pornography

Intellectual Property Part 2 Pornography By Jeremy Parmenter What is pornography Pornography is the explicit portrayal of sexual subject matter Can be found as books, magazines, videos The web has images, tube sites, and pay sites scattered with porn Statistics 12% of total websites are pornography websites 25% of total daily search engine requests are pornographic requests 42.7% of internet users who view pornography 34% internet users receive unwanted exposure to sexual material $4.9 billion in internet pornography sales 11 years old is the average age of first internet exposure to pornography Innovations ● Richard Gordon created an e-commerce start up in mid- 90s that was used on many sites, most notably selling Pamela Anderson/Tommey Lee sex tape ● Danni Ashe founded Danni's Hard Drive with one of the first streaming video without requiring a plug-in ● Adult content sites were one of the first to use traffic optimization by linking to similar sites ● Live chat during the early days of the web ● Pornographic companies were known to give away broadband devices to promote faster connections Negative Impacts ● Between 2001-2002 adult-oriented spam rose 450% ● Malware such as Trojans and video codecs occur most often on porn sites ● Domain hijacking, using fake documents and information to steal a site ● Pop-ups preventing users from leaving the site or infecting their computer ● Browser hijacking adware or spyware manipulating the browser to change home page or search engine to a bogus site, including pay-per-click adult site ● Accessibility -

A Critique of the Digital Millenium Copyright Act's

THINKPIECE ACRITIQUE OF THE DIGITAL MILLENIUM COPYRIGHT ACT’S EXEMPTION ON ENCRYPTION RESEARCH: IS THE EXEMPTION TOO NARROW? VICKY KU I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................. 466 II. PART I: WHAT IS ENCRYPTION RESEARCH? ABRIEF HISTORY470 III. PART II: OVERVIEW OF SECTION 1201(A)(1) OF THE DMCA474 A. WHAT DOES IT SAY?.................................................... 474 B. WHAT WAS ITS INTENDED PURPOSE? .......................... 474 C. WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF 1201(G)? ........................... 475 IV.PART III: IMPACT OF SECTION 1201(G) OF THE DMCA ON ENCRYPTION RESEARCH .................................................. 485 A. WHO IN THE ACADEMIC COMMUNITY HAS BEEN AFFECTED? .................................................................................. 485 V. PART IV: PROPOSED CHANGES TO THE DMCA.................. 488 VI.CONCLUSION ..................................................................... 489 Jointly reviewed and edited by Yale Journal of Law & Technology and International Journal of Communications Law & Policy. Author’s Note. 466 YALE JOURNAL OF LAW &TECHNOLOGY 2004-2005 ACRITIQUE OF THE DIGITAL MILLENIUM COPYRIGHT ACT’S EXEMPTION ON ENCRYPTION RESEARCH: IS THE EXEMPTION TOO NARROW? VICKY KU Section 1201(g) of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) is offered as an exemption for encryption research.1 However, the drafting of the exemption contradicts the purpose of copyright legislation under the terms of the Constitution, which is based upon the idea that the welfare -

Kyoobur9000 Interview -- How Did You Come to Logo Editing? I Joined Youtube Back in 2010 and I Was Always Fasc

Kyoobur9000 interview -- How did you come to logo editing? I joined YouTube back in 2010 and I was always fascinated by these videos where people would take their video programs and apply it, plug-in after plug-in after plug-in basically to make it unrecognizable. And that’s initially what I planned on having my channel be but I actually discovered that there were some pretty cool things I could do without, you know, tearing the video apart. So, I just kinda started by trying certain plug-ins or combinations of plug-ins and figured, hey this might sound cool or this might look cool and you know, it just worked out. What was going on at the time when you joined YouTube. You were seeing other production company idents or flips of other sources? What were you seeing and what were your inspirations?.. searching around on YouTube? Yes, there were other YouTube channels that did some work, you know there’s an audio effect called G-Major and um, people would apply that to idents and logos. So that’s what kinda got me attracted to logo editing. And the plug-ins really came from me playing with the video programs I had at my disposal. Even though it wasn’t my initial plan it was mainly that exposure to logos from G-Major that made it the point of my channel. Because you were quite young when you started, right? I was, actually I was just about to start high-school. So how did you come to picking your sources?. -

Unintended Consequences: Twelve Years Under the DMCA

Unintended Consequences: Twelve Years under the DMCA By Fred Von Lohmann, [email protected] February 2010 ELECTRONIC FRONTIER FOUNDATION eff.org Unintended Consequences: Twelve Years under the DMCA This document collects reported cases where the anti-circumvention provisions of the DMCA have been invoked not against pirates, but against consumers, scientists, and legitimate compet- itors. It will be updated from time to time as additional cases come to light. The latest version can always be obtained at www.eff.org. 1. Executive Summary Since they were enacted in 1998, the “anti-circumvention” provisions of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (“DMCA”), codified in section 1201 of the Copyright Act, have not been used as Congress envisioned. Congress meant to stop copyright infringers from defeating anti-piracy protections added to copyrighted works and to ban the “black box” devices intended for that purpose. 1 In practice, the anti-circumvention provisions have been used to stifle a wide array of legitimate activities, rather than to stop copyright infringement. As a result, the DMCA has developed into a serious threat to several important public policy priorities: The DMCA Chills Free Expression and Scientific Research. Experience with section 1201 demonstrates that it is being used to stifle free speech and scientific research. The lawsuit against 2600 magazine, threats against Princeton Profes- sor Edward Felten’s team of researchers, and prosecution of Russian programmer Dmitry Sklyarov have chilled the legitimate activities of journalists, publishers, scientists, stu- dents, program¬mers, and members of the public. The DMCA Jeopardizes Fair Use. By banning all acts of circumvention, and all technologies and tools that can be used for circumvention, the DMCA grants to copyright owners the power to unilaterally elimi- nate the public’s fair use rights. -

1 in the SUPERIOR COURT of FULTON COUNTY STATE of GEORGIA DONNA CURLING, an Individual; ) ) COALITION for GOOD ) GOVERNANC

IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF FULTON COUNTY STATE OF GEORGIA DONNA CURLING, an individual; ) ) COALITION FOR GOOD ) GOVERNANCE, a non-profit corporation ) organized and existing under Colorado ) Law; ) ) DONNA PRICE, an individual; ) ) JEFFREY SCHOENBERG, an individual; ) ) LAURA DIGGES, an individual; ) ) WILLIAM DIGGES III, an individual; ) ) RICARDO DAVIS, an individual; ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) CIVIL ACTION ) FILE NO.: 2017cv292233 BRIAN P. KEMP, in his individual ) capacity and his official capacity as ) Secretary of State of Georgia and ) Chair of the STATE ELECTION BOARD; ) DEMAND FOR ) JURY TRIAL DAVID J. WORLEY, REBECCA N. ) SULLIVAN, RALPH F. “RUSTY” ) SIMPSON, and SETH HARP, in their ) individual capacities and their official ) capacities as members of the STATE ) ELECTION BOARD; ) ) THE STATE ELECTION BOARD; ) ) RICHARD BARRON, in his individual ) capacity and his official capacity as ) 1 Director of the FULTON COUNTY ) BOARD OF REGISTRATION AND ) ELECTIONS; ) ) MARY CAROLE COONEY, VERNETTA ) NURIDDIN, DAVID J. BURGE, STAN ) MATARAZZO and AARON JOHNSON ) in their individual capacities and official ) capacities as members of the FULTON ) COUNTY BOARD OF REGISTRATION ) AND ELECTIONS; ) ) THE FULTON COUNTY BOARD OF ) REGISTRATION AND ELECTIONS; ) ) MAXINE DANIELS, in her individual ) capacity and her official capacity as ) Director of VOTER REGISTRATIONS ) AND ELECTIONS FOR DEKALB ) COUNTY; ) ) MICHAEL P. COVENY, ANTHONY ) LEWIS, LEONA PERRY, SAMUEL ) E. TILLMAN, and BAOKY N. VU ) in their individual capacities and official ) capacities as members of the DEKALB ) COUNTY BOARD OF REGISTRATIONS ) AND ELECTIONS; ) ) THE DEKALB COUNTY BOARD OF ) REGISTRATIONS AND ELECTIONS; ) ) JANINE EVELER, in her individual ) capacity and her official capacity as ) Director of the COBB COUNTY ) BOARD OF ELECTIONS AND ) REGISTRATION; ) ) PHIL DANIELL, FRED AIKEN, JOE ) PETTIT, JESSICA BROOKS, and ) 2 DARRYL O.