Fitting the Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading and Resource Guide

IN PHILADELPHIA EVERYONE IS READING JANUARY 8 – MARCH 20, 2008 COMPANION BOOKS A PROJECT OF THE OFFICE OF THE MAYOR AND THE FREE LIBRARY OF PHILADELPHIA Lead Sponsor: www.freelibrary.org RESOURCE GUIDE One Book, One Philadelphia is a joint project of the Mayor’s Office and the Free Library of Philadelphia. The mission of the program—now entering its sixth year—is to promote reading, literacy, library usage, and community building throughout the Greater Philadelphia region. This year, the One Book, One Philadelphia Selection Committee has chosen Dave Eggers’ What Is the What as the featured title of the 2008 One Book program. To engage the widest possible audience while encouraging intergenerational reading, two thematically related companion books were also selected for families, children, and teens—Mawi Asgedom’s Of Beetles and Angels: A Boy’s Remarkable Journey from a Refugee Camp to Harvard and Mary Williams’ Brothers In Hope: The Story of the Lost Boys of Sudan. Both of these books provide children and adults opportunities to further understand and discuss the history of the conflict in Sudan, as well as other issues of violence in the world and in our own region. Contents Read one, or read them all—just be sure to get 2 Companion Titles out there and share your opinions! 3 Questions for Discussion What Is the What For more information on the 2008 One Book, Of Beetles and Angels: One Philadelphia program, please visit our A Boy’s Remarkable Journey from a Refugee Camp to Harvard website at www.freelibrary.org, where you Brothers In Hope: The Story can view our calendar of events, download of the Lost Boys of Sudan podcasts of One Book author appearances, 6 Timeline: A Recent History of Sudan and post comments on our One Book Blog. -

American Teacher PK

American Teacher A Film By Vanessa Roth 81 minutes, color, HD, English, USA, 2011 FIRST RUN FEATURES The Film Center Building, 630 Ninth Ave. #1213 New York, NY 10036 Tel (212) 243-0600 | Fax (212) 989-7649 Website: www.firstrunfeatures.com Email: [email protected] http://firstrunfeatures.com/americanteacher Advance Praise for American Teacher “This is an important film that raises important questions about America’s teachers. It should spark a much-needed conversation.” – Arne Duncan, U.S. Secretary of Education “It was moving, overwhelming and made me love (even more) all the teachers out there doing what I think is the toughest job.” – Sarah , Isabel Allende’s blog “Empathetically narrated by Matt Damon, [this] engaging pic is nicely assembled in all departments.” – Dennis Harvey, Variety “Powerful—‘How long can we let this go on?,’ you wonder—and could generate some important conversations… As one of the teachers featured in the film said in a panel discussion after the preview, ‘I think it’s about time there’s a film like this.’” – Anthony Rebora, Education Week’s Teaching Now blog “Their stories will make your heart drop, but their unwavering strength is uplifting and their stories need to be out there. This film is a remarkable platform for them. American Teacher goes inside and beyond the classroom and shows that quality education starts with great educators—but it must start by making things better for them.” – Karen Datangel, Karen-On “Captivating…shows, through gripping portraits like Benner’s, why we must value our nation’s educators more by paying them more.” – ABCDE Blog “American Teacher exposes the reality of any normal teacher’s life, calls for action, and raises some important questions.” – Isabel Allende Synopsis American Teacher is the feature-length documentary created and produced by Vanessa Roth, Nínive Calegari, Dave Eggers, and Brian McGinn. -

Literature for the 21St Century Summer 2013 Coursebook

Literature for the 21st Century Summer 2013 Coursebook PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sun, 26 May 2013 16:12:52 UTC Contents Articles Postmodern literature 1 Alice Munro 14 Hilary Mantel 20 Wolf Hall 25 Bring Up the Bodies 28 Thomas Cromwell 30 Louise Erdrich 39 Dave Eggers 44 Bernardo Atxaga 50 Mo Yan 52 Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out 58 Postmodernism 59 Post-postmodernism 73 Magic realism 77 References Article Sources and Contributors 91 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 94 Article Licenses License 95 Postmodern literature 1 Postmodern literature Postmodern literature is literature characterized by heavy reliance on techniques like fragmentation, paradox, and questionable narrators, and is often (though not exclusively) defined as a style or trend which emerged in the post–World War II era. Postmodern works are seen as a reaction against Enlightenment thinking and Modernist approaches to literature.[1] Postmodern literature, like postmodernism as a whole, tends to resist definition or classification as a "movement". Indeed, the convergence of postmodern literature with various modes of critical theory, particularly reader-response and deconstructionist approaches, and the subversions of the implicit contract between author, text and reader by which its works are often characterised, have led to pre-modern fictions such as Cervantes' Don Quixote (1605,1615) and Laurence Sterne's eighteenth-century satire Tristram Shandy being retrospectively inducted into the fold.[2][3] While there is little consensus on the precise characteristics, scope, and importance of postmodern literature, as is often the case with artistic movements, postmodern literature is commonly defined in relation to a precursor. -

The Interrelationship Between Testifier, Author, and Reader in Dave Eggers's What Is T

“THE COLLAPSIBLE SPACE BETWEEN US”: THE INTERRELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TESTIFIER, AUTHOR, AND READER IN DAVE EGGERS’S WHAT IS THE WHAT A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English By Allison Moore Correll, B.A. Washington, D.C. April 24, 2009 Acknowledgments First, I am indebted to my family and friends for their unwavering support and encouragement. Thank you for allowing me to discuss my thoughts passionately and freely and for taking your own interest in the work of this thesis. To my graduate school colleagues Kimberly Hall, Michelle Repass, and David Weinstein, I am beyond grateful for the many discussions we had that enabled me to trace out my ideas and intentions for this thesis. This project would not have been completed without those conversations, your suggestions, and more simply put, your friendship. This project would have been impossible without Dr. Patricia E. O’Connor. Her enthusiasm for the subject, along with her probing questions, helped me complete a thesis of which I am both passionate and proud. Professor Carolyn Forché served as a source of inspiration both inside and outside of the classroom. To all of my professors who guided me (and inspired me) along the way, thank you. Finally, thank you to Valentino Achak Deng and Dave Eggers for their tenacity and commitment in completing the project that became What Is the What . This book reaffirmed my faith in the power of literature—that a book can not only be good, but it can do good as well. -

How We Are Hungry

Table of Contents Title Page Dedication Praise ANOTHER WHAT IT MEANS WHEN A CROWD IN A FARAWAY NATION TAKES A SOLDIER REPRESENTING YOUR OWN NATION, SHOOTS HIM, DRAGS HIM FROM HIS VEHICLE AND THEN MUTILATES HIM IN THE DUST THE ONLY MEANING OF THE OIL-WET WATER ON WANTING TO HAVE AT LEAST THREE WALLS UP BEFORE SHE GETS HOME CLIMBING TO THE WINDOW, PRETENDING TO DANCE SHE WAITS, SEETHING, BLOOMING QUIET YOUR MOTHER AND I NAVEED NOTES FOR A STORY OF A MAN WHO WILL NOT DIE ALONE ABOUT THE MAN WHO BEGAN FLYING AFTER MEETING HER UP THE MOUNTAIN COMING DOWN SLOWLY WHEN THEY LEARNED TO YELP AFTER I WAS THROWN IN THE RIVER AND BEFORE I DROWNED About the Author ALSO BY DAVE EGGERS Copyright Page THIS BOOK IS FOR CHRIS Acclaim for Dave Eggers’s HOW WE ARE HUNGRY A San Francisco Chronicle Best Book of the Year “Full of the raw stuff of lives. The pain and the anger. Emotions that get mixed up and change from one minute to the next. The wonder and the joy. It’s all condensed and crafted, working, that’s what fiction is. But it feels raw, and it’s exhilarating. And that’s not even getting into how electrically funny Eggers can be.” —The Globe and Mail (Toronto) “ ‘After I Was Thrown in the River and Before I Drowned’ is a small tour de force that ratifies [Eggers’s] ability to write about anything with style and vigor and genuine emotion.” —The New York Times “Haunting character-driven narratives. -

Press Release for the Best American Nonrequired Reading 2004 Edited

Press Release The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2004 edited by Dave Eggers introduction by Viggo Mortensen • About the Book • About the Editors About the Book With returning editor Dave Eggers and his troop of writing workshop students from 826 Valencia at the helm, The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2004 (Houghton Mifflin; publication date: October 14, 2004) is in its third year of publication. This year's contributors present work ranging from the hilarious to the macabre, from the journalistic essay to the graphic one-frame story. Daniel Alarcón leads us through a maze of psychologically riveting events following the death of a young reporter's philandering father in Lima in "City of Clowns." The narrator, refusing to display any emotion about his father's death, disappears deep into the swirling city on the hunt for a story that will allow him distance from his own life. In a brilliant take on ghost stories, Gina Ochsner's "Hidden Lives of Lakes" bridges the world between human and spirit when two couples discover their dead neighbors and relatives living full, new lives under the thick ice of a frozen winter lake. Back in the real world, Michelle Tea contributes a sharp, moving, and important piece of journalism reporting on Camp Trans, a transgendered/transsexual protest camp set up outside the Michigan Womyn's Music Festival after trasgendered attendees learned of the festival's policy to exclude them. While Tea never loses sight of her main agenda, she fills out the report with fascinating interviews, detailed accounts of camp life and politics, and a consistently empathetic portrayal of all the parties involved. -

What Is the What Press Info

WHAT IS THE WHAT a novel by DAVE EGGERS Separated from his family, Valentino Achak Deng becomes a refugee in war-ravaged southern Sudan. His travels bring him in contact with enemy soldiers, with liberation rebels, with hye- nas and lions, with disease and starvation, and with deadly murahaleen (militias on horse- back)—the same sort who currently terrorize Darfur. Based closely on actual experiences, What is the What is heartrending and astonishing, filled with adventure, suspense, tragedy and, finally, triumph. “Dave Eggers has done something remarkable with this book. He has managed to cross many barriers both real and artificial to tell the story of one man’s tragedy and triumph in a way that emphasizes his simple humanity above the drama of his ter- rible situation. It is a book that shows there is no reason why geographical and cul- tural divides should prevent us from attempting to understand each other as citi- zens of this world.” —UZODINMA IWEALA, author of Beasts of No Nation “I cannot recall the last time I was this moved by a novel. What is the What is that rare book that truly deserves the overused and scarcely warranted moniker of ‘sprawling epic.’ Told with humor, humanity, and bottomless compassion for his subject, one Valentino Achak Deng, Eggers shows us the hardships, disillusions, and hopes of the long suffering people of southern Sudan. This is the story of one boy’s astonishing capacity to endure atrocity after atrocity and yet refuse to abandon decency, kindness, and hope for home and acceptance. It is impossible to read this book and not be humbled, enlightened, transformed. -

A Book to Read Over the Summer? but It's My Vacation!

What?! A book to read over the summer? But it’s my vacation! Yes, you received your first college assignment before even starting classes. Actually, thousands of other freshmen were also reading books over the summer in preparation for their first days on campus. Many colleges and universities across the nation have instituted First Year and/or Campus reading programs, but why? There are many reasons for having students – and faculty and staff – read a common book. As a new student, you are entering a community of other learners with a variety of life experiences. A common reading program allows incoming students to have at least one thing in common and something to talk about right from movein day. Reading a common book provides numerous opportunities to connect with, engage in, and contribute to your new community. Common reading programs also set the tone for college academic expectations. College will be work and will demand that you challenge yourself in many ways; participating in a shared reading program is one way to start this academic journey. According to a 2007 report from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), among seventeenyearolds, the percentage of nonreaders has doubled, from nine percent in 1984 to nineteen percent in 2004. The fact is that Americans of most age levels are reading less, which, according to the study, results in lower reading scores and civic, social, and economic implications. The NEA also found that “literary readers are more likely than nonreaders to engage in positive civic and individual activities – such as volunteering, attending sports or cultural events, and exercising.” Overall, reading literary fiction and nonfiction, not just the latest issue of People or checking the news on CNN.com, is an important part of being a college student and in being a thoughtful, engaged citizen of your community and your world. -

Dave Eggers' a Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius Subverts The

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 6-17-2009 This was uncalled for : Dave Eggers' A heartbreaking work of staggering genius subverts the genre of traditional autobiography as an attempt at rendering his life Krystal Alvarez Florida International University DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14031607 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Alvarez, Krystal, "This was uncalled for : Dave Eggers' A heartbreaking work of staggering genius subverts the genre of traditional autobiography as an attempt at rendering his life" (2009). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1265. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1265 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida THIS WAS UNCALLED FOR: DAVE EGGERS' A HEARTBREAKING WORK OF STAGGERING GENIUS SUBVERTS THE GENRE OF TRADITIONAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY AS AN ATTEMPT AT RENDERING HIS LIFE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERS OF ARTS in ENGLISH by Krystal Alvarez 2009 To: Dean Kenneth Furton College of Arts and Sciences This thesis, written by Krystal Alvarez, and entitled This Was Uncalled For: Dave Eggers' A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius Subverts the Genre of Traditional Autobiography as an Attempt at Rendering His Life, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. -

How We Are Hungry by Dave Eggers

Read and Download Ebook How We Are Hungry... How We Are Hungry Dave Eggers PDF File: How We Are Hungry... 1 Read and Download Ebook How We Are Hungry... How We Are Hungry Dave Eggers How We Are Hungry Dave Eggers "Another" "What It Means When a Crowd in a Faraway Nation Takes a Soldier Representing Your Own Nation, Shoots Him, Drags Him from His Vehicle and Then Mutilates Him in the Dust" "The Only Meaning of the Oil-Wet Water" "On Wanting to Have Three Walls Up Before She Gets Home" "Climbing to the Window, Pretending to Dance" "She Waits, Seething, Blooming" "Quiet" "Your Mother and I" "Naveed" "Notes for a Story of a Man Who Will Not Die Alone" "About the Man Who Began Flying After Meeting Her" "Up the Mountain Coming Down Slowly" "After I Was Thrown in the River and Before I Drowned" From the Trade Paperback edition. How We Are Hungry Details Date : Published October 11th 2005 by Vintage (first published 2005) ISBN : 9781400095568 Author : Dave Eggers Format : Paperback 224 pages Genre : Short Stories, Fiction, Contemporary, Literature Download How We Are Hungry ...pdf Read Online How We Are Hungry ...pdf PDF File: How We Are Hungry... 2 Read and Download Ebook How We Are Hungry... Download and Read Free Online How We Are Hungry Dave Eggers PDF File: How We Are Hungry... 3 Read and Download Ebook How We Are Hungry... From Reader Review How We Are Hungry for online ebook Chris Tempel says I read only a few sentences in this book while browsing the library. -

Zeitoun and Zeitoun

Promotor Prof. dr. Stef Craps Universiteit Gent Copromotor Prof. dr. Pieter Vermeulen KU Leuven Decaan Prof. dr. Marc Boone Rector Prof. dr. Anne De Paepe Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch, door fotokopieën, opnamen, of enige andere manier, zonder voorafgaande toestemming van de uitgever. Faculteit Letteren & Wijsbegeerte Sean Bex Dave Eggers and Human Rights Culture Proefschrift voorgelegd tot het behalen van de graad van Doctor in Letterkunde 2016 Acknowledgements As much as the myth of the solitary and confined doctoral researcher may seem to confirm it, this research project on human rights culture and Dave Eggers would not have been possible without the considerable support of a great many people. Indeed, I have been able to count on a wide range of colleagues, friends, and family who were always there to celebrate every victory – however small – and overcome any obstacle – however daunting. First and foremost, I would like to mention my supervisors, Prof. Stef Craps and Prof. Pieter Vermeulen. I want to thank them both for the faith they placed in me to take on this FWO-funded research project and for the convivial relationship we maintained throughout. In an academic world where a PhD depends so heavily on the working relationships researchers and their supervisors have, I was exceptionally lucky to work with two who were eminently approachable and intellectually engaging in equal measure. My thanks also go out to the members of my Doctoral Guidance Committee (DGC), Prof. -

San Diego Public Library New Additions October 2009

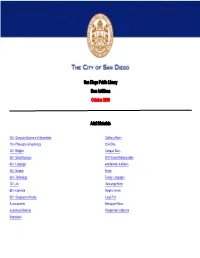

San Diego Public Library New Additions October 2009 Adult Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities California Room 100 - Philosophy & Psychology CD-ROMs 200 - Religion Compact Discs 300 - Social Sciences DVD Videos/Videocassettes 400 - Language eAudiobooks & eBooks 500 - Science Fiction 600 - Technology Foreign Languages 700 - Art Genealogy Room 800 - Literature Graphic Novels 900 - Geography & History Large Print Audiocassettes Newspaper Room Audiovisual Materials Wangenheim Collection Biographies Fiction Call # Author Title FIC/ABDULLAH Abdullah, Shaila, 1971- Saffron dreams : a novel FIC/ADAMS Adams, Will, 1963- The Alexander cipher FIC/ADLER Adler, Elizabeth (Elizabeth A.) There's something about St. Tropez FIC/AKPAN Akpan, Uwem. Say you're one of them FIC/ALBOM Albom, Mitch, 1958- For one more day FIC/ALCORN Alcorn, Randy C. Safely home FIC/ALEXANDER Alexander, Hannah. A killing frost FIC/ALLEN Allen, Sarah Addison. Garden spells FIC/ALLEN Allen, Sarah Addison. The sugar queen FIC/ALLENDE Allende, Isabel. The infinite plan : a novel FIC/AMIS Amis, Kingsley. The green man FIC/ANDERSON Anderson, Kevin J., 1962- Enemies & allies FIC/ANDREWS Andrews, Mary Kay, 1954- Hissy fit FIC/APPELFELD Appelfeld, Aron. Laish FIC/ARELLANO Arellano, Robert. Havana lunar [MYST] FIC/ATHERTON Atherton, Nancy. Aunt Dimity and the next of kin FIC/ATKINSON Atkinson, Kate. Behind the scenes at the museum FIC/ATWOOD Atwood, Margaret, 1939- The year of the flood : a novel FIC/AUEL Auel, Jean M. The mammoth hunters FIC/AUEL Auel, Jean M. The plains of passage FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane, 1775-1817. Sense and sensibility FIC/BADEN Baden, Michael M. Skeleton justice : a novel [MYST] FIC/BAIN Bain, Donald, 1935- Murder on parade : a Murder, she wrote mystery : a novel [SCI-FI] FIC/BAKKER Bakker, R.