An Interview with DAVE EGGERS and MIMI LOK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dave Eggars Press Release

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE Contacts: Jon Newman SEPTEMBER 12, 2007 (804) 788-1414 Russ Martz (412) 497-5775 Author and Founder of Children’s Writing Laboratories Honored with $250,000 Heinz Award for Arts and Humanities Youngest-ever recipient Dave Eggers recognized for literary and philanthropic achievements PITTSBURGH, September 12, 2007 – A critically acclaimed novelist whose meteoric commercial success has helped propel him into the worlds of philanthropy, advocacy and education has been selected to receive the 13th annual Heinz Award in the Arts and Humanities, among the largest individual achievement prizes in the world. Dave Eggers of San Francisco, the author of best-selling works in both fiction and nonfiction as well as the founder of inner-city writing laboratories for youth and a publishing house for writers, is among six distinguished Americans selected to receive one of the $250,000 awards, presented in five categories by the Heinz Family Foundation. At age 37, he is the youngest-ever recipient of the Heinz Award. “Dave Eggers is not only an accomplished and versatile man of letters but the protagonist of a real-life story of generosity and inspiration,” said Teresa Heinz, chairman of the Heinz Family Foundation. “As a young man, he has infused his love of writing and learning into the broader community, nurturing the talents and aspirations of a new generation of writers and creating new outlets for a range of literary expression. Whether as a writer, mentor or benefactor, he has provided voice to the value of human potential.” - more - Page 2 of 4 - Heinz Awards, Arts and Humanities Having burst on the literary scene with his autobiographical bestseller, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, before he was 30, Mr. -

ORGANIZATION DESCRIPTION: 826NYC Is a Tutoring and Literacy

ORGANIZATION DESCRIPTION: 826NYC is a tutoring and literacy center dedicated to helping underserved students, ages 6-18, with expository and creative writing, homework, college preparation, and other essential skills. Modeled after 826 Valencia (founded in 2002 by Dave Eggers and Nínive Calegari in San Francisco’s Mission District), 826NYC is located in the Park Slope neighborhood of Brooklyn and is fronted by the world famous Brooklyn Superhero Supply Store. The revenues from the store support 826NYC and its student programming. 826NYCs work is based on the understanding that great leaps in learning can happen with one-on-one attention, and that strong writing skills are fundamental to future success. Through the work of talented staff and the assistance of more than 1,000 volunteers, 826NYC provides after-school tutoring, class field trips, writing workshops, in-schools programs (including special projects and full-time staffing of a writers’ at the Williamsburg Library), journal and book publication, and college preparation—all free of charge. 826NYC is especially committed to supporting teachers and publishing student work. 826 tutoring and literacy centers are in seven other cities—San Francisco, Los Angeles, Ann Arbor, Chicago, Seattle, Boston, and Washington, DC. These eight chapters operate under the umbrella of 826 National, which coordinates the work of the chapters, implements best practices as established by the chapters and the 826 National board, and raises funds to support the work of 826 National and the chapters. 826 was chosen by GOOD Magazine as one of the top 30 companies to work at. 826NYC, the other seven chapters, and 826 National are separate 501(c)(3) organizations with their own boards of directors. -

Los Angeles Times 826 Brings Reading, Writing and Robots to Echo

Los Angeles Times: 826 brings reading, writing and robots to Echo Park 1/8/08 3:12 PM http://www.latimes.com/features/books/la-et-eggers31dec31,0,7374625.story?coll=la-books-headlines From the Los Angeles Times BOOK NEWS 826 brings reading, writing and robots to Echo Park A time-travelers' convenience store? Must be a new literacy center from author Dave Eggers' crew. By Steffie Nelson Special to The Times December 31, 2007 At the grand opening of the Echo Park Time Travel Mart on Dec. 15, the Robot Emotions were going like hot cakes (happiness and schadenfreude were the top sellers). The mystery product Chubble, on the other hand, available in more than 50 different varieties, wasn't really moving. A worker dressed like a cowboy shrugged. "It's really hot in the future." There were also bottles of optimism and socialism, dinosaur eggs, woolly mammoth chili, a bag of shade, a King Tut action figure and all manner of head wear, tri-corner hats as well as bonnets. Fortunately, it was a chilly night, because the slushie machine was on the blink. "Out of order. Come back yesterday," read the handwritten sign. This convenience store for time travelers, whose motto is "Whenever you are, we're already then," is the whimsical retail component of the new Echo Park 826LA, a free literacy and writing center for kids that was started by author Dave Eggers in San Francisco and then spun off in New York; Chicago; Ann Arbor, Mich.; Seattle; and Boston. Located on a busy stretch of Sunset Boulevard and scheduled to open for drop-in tutoring Jan. -

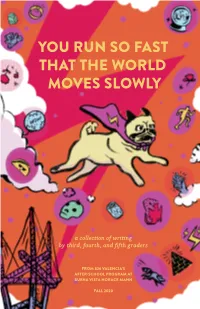

You Run So Fast That the World Moves Slowly

YOU RUN SO FAST THAT THE WORLD MOVES SLOWLY a collection of writing by third, fourth, and fifth graders FROM 826 VALENCIA’S AFTER-SCHOOL PROGRAM AT BUENA VISTA HORACE MANN FALL 2020 YOU RUN SO FAST THAT THE WORLD MOVES SLOWLY BUENA VISTA HORACE MANN AFTER-SCHOOL PROGRAM FALL 2020 PROGRAM LEADS Diana Garcia Ashley Smith OTHER PROGRAM STAFF Emilia Rivera Arel Wiederholt Kassar INTERNS & TUTORS Saffron Agrawal Darren Lee Luis Sepulveda Jason Baum Selina Lee Kano Umezaki Tyler Beneke Masani Limutau Aaliyah Williams Matthew Bussa Noa Mendoza Anne Wong Claire Ewers Rose Mitchell Billie Zeng Emilia Fernandez Claire "Tomi" Osawa Yuli Zhang Hung Ella Gardner Natalia Quesada Marshall Maura Kealey Opal Jane Ratchye SCHOOL PARTNERS BVHM Teachers and Staff COVER ILLUSTRATION Montana Manalo COPY EDITOR James O'Hagan MISSION TENDERLOIN MISSION BAY 826 Valencia St. 180 Golden Gate Ave. 1310 4th St. San Francisco, CA San Francisco, CA San Francisco, CA 94110 94102 94158 826valencia.org Published December 2020 by 826 Valencia. Copyright © 2020 by 826 Valencia. The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and the authors’ imaginations, and do not reflect those of 826 Valencia. We support student publishing and are thrilled that you’ve picked up this book! 826 Valencia and its free programs are fueled by generous contributions from companies, organizations, government agencies, and individuals who provide more than 95% of our budget. 826 Valencia’s partnership with Buena Vista Horace Mann K-8 and this publication are made possible in part by support from the Dow Jones Foundation, GGS Foundation, Fleishhacker Foundation, Hellman Foundation, Jamestown Community Center, Marky A. -

Brooklyn Secret

MICHELLE YOUNG AND AUGUSTIN PASQUET SECRET BROOKLYN JONGLEZ PUBLISHING JONGLEZ PUBLISHING TO THE NORTH: DOWNTOWN BROOKLYN LONG ISLAND UNIVERSITY 19 owntown Brooklyn, around the intersection of Flatbush Avenue BASKETBALL COURT Dand Fulton Street, was hailed as the “Times Square of Brooklyn,” by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1928. This was the year that the Paramount Theatre was under construction. The accompanying map showed 12 A gym inside a historic movie theater theaters all within a few blocks, and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle called it 161 Ashland Place the “Hub of the Largest Theatre District in the world, excepting only Brooklyn, NY 11201 New York.” When the Paramount opened on November 23rd, 1928, Transport: B/Q/R to DeKalb Avenue the total combined capacity of the theaters in this area was 25,000 seats. The opening was such an important one that local businesses, such as Loeser’s department store and Joe’s Restaurant, took out advertisements to welcome the new venue. In addition to movies, the Paramount hosted famous performers like Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington and Frank Sinatra. Downtown Brooklyn has regained some of its entertainment cred with the arrival of the Barclays Center, the addition of BRIC Arts|Media House, and the continued excellence of the Brooklyn Academy of Music. But many of the old theaters are gone. One notable exception lies hidden inside the Long Island University Athletic Center. The basketball court sits amid an opulent backdrop, the auditorium of the former Paramount Theatre. The scoreboard sits in front of the grand stage proscenium and the original details of the theater are well preserved on the ornamented walls and arched, latticed ceiling. -

Beyond 'Literacy Crusading': Neocolonialism, the Nonprofit Industrial Complex, and Possibilities of Divestment

Community Literacy Journal Volume 15 Issue 1 Special Issue: Community-Engaged Article 6 Writing and Literacy Centers Spring 2021 Beyond 'Literacy Crusading': Neocolonialism, the Nonprofit Industrial Complex, and Possibilities of Divestment Anna Zeemont Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/communityliteracy Recommended Citation Zeemont, Anna. “Beyond ‘Literacy Crusading’: Neocolonialism, the Nonprofit Industrial Complex, and Possibilities of Divestment.” Community Literacy Journal, vol. 15, no. 1, 2021, pp. 70–91, doi:10.25148/ clj.15.1.009365. This work is brought to you for free and open access by FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Community Literacy Journal by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. community literacy journal Beyond ‘Literacy Crusading’: Neocolonialism, the Nonprofit Industrial Complex, and Possibilities of Divestment Anna Zeemont Abstract This article highlights how contemporary structural forces—the intertwined systems of racism, xenophobia, gentrification, and capitalism—have materi- al consequences for the nature of community literacy education. As a case study, I interrogate the rhetoric and infrastructure of a San Francisco K-12 literacy nonprofit in the context of tech-boom gentrification, triggering the mass displacement of Latinx residents. I locate the nonprofit in longer histo- ries of settler colonialism and migration in the Bay Area to analyze how the organization’s rhetoric—the founder’s TED talk, its website, the mural on the building’s façade—are structured by racist logics that devalue and homog- enize the literacy and agency of the local community, perpetuating white “possessive investments” (Lipsitz) in land, literacy, and education. -

Curriculum Guide 5Th - 8Th Grades

Final drawing for Where the Wild Things Are, © 1963 by Maurice Sendak, all rights reserved. Curriculum Guide 5th - 8th Grades In a Nutshell:the Worlds of Maurice Sendak is on display jan 4 - feb 24, 2012 l main library l 301 york street In a Nutshell: The Worlds of Maurice Sendak was organized by the Rosenbach Museum & Library, Philadelphia, and developed by Nextbook, Inc., a nonprofit organization dedicated to supporting Jewish literature, culture, and ideas, and the American Library Association Public Programs Office. The national tour of the exhibit has been made possible by grants from the Charles H. Revson Foundation, the Righteous Persons Foundation, the David Berg Foundation, and an anonymous donor, with additional support from Tablet Magazine: A New Read on Jewish Life. About the Exhibit About Maurice Sendak will be held at the Main Library, 301 York St., downtown, January 4th to February 24th, 2012. Popular children’s author Maurice Sendak’s typically American childhood in New York City inspired many of his most beloved books, such as Where the Wild Things Are and In the Night Kitchen. Illustrations in those works are populated with friends, family, and the sights, sounds and smells of New York in the 1930s. But Sendak was also drawn to photos of ancestors, and he developed a fascination with the shtetl world of European Jews. This exhibit, curated by Patrick Rodgers of the Rosenbach Museum & Library Maurice Sendak comes from Brooklyn, New York. in Philadelphia, reveals the push and pull of New and Old He was born in 1928, the youngest of three children. -

Dave Eggers PR2.Indd

Jules Maeght Gallery DAVE EGGERS: IDAHO February 11 to May 7, 2016 Opening Reception: February 11, 2016 - 6 to 9 pm 5:30 pm : Dave Eggers in conversation with Natasha Boas, Press and VIP preview FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DAVE EGGERS : IDAHO Jules Maeght Gallery 149 Gough Street @ Oak February 11, 2016 - May 7, 2016 January 6th, 2016 - SAN FRANCISCO - The Jules Maeght Gallery is proud to present DAVE EGGERS: IDAHO, a solo exhibition of newly commissioned work made specifically for the gallery space and organized by Jules Maeght and Natasha Boas. Eggers has been known for his works on paper and wood that usually involve renderings of animals paired with text. This new show at the Jules Maeght Gallery vastly expands Eggers’ repertoire to include sculptures made of steel and fur, interactive kinetic works, oil on canvas, acrylic on wood, and installation. “The Jules Maeght Gallery is such an inspiring space”, Eggers says. “Its size and light freed me up to take on some projects I’d been thinking about for a long time.” Using the loose theme of Idaho as a starting point, the show will invite viewers to participate. “There will be a number of pieces that people can interact with, including the pedicab”. For the show, Eggers has converted a working pedicab into an operable sculpture made of reclaimed steel. The show will also feature large-scale oil paintings, a multi-panel narrative work, and a wall of mounted animal heads. “The taxidermy will be a little different than what you expect,” Eggers says. The animals will appear lifelike and will have an interactive element, but do not use any animal matter. -

By Dave Eggers : a Narrative Consisting of a Peculiar Form, a Traumatic Content and a Critical Commentary on Western Civilization and Culture

The Complexity of What is the What, the Autobiography of Valentino Achak Deng (2006) by Dave Eggers : A Narrative Consisting of a Peculiar Form, a Traumatic Content and a Critical Commentary on Western Civilization and Culture Eline De Moor Master Linguistics and Literature, Dutch-English, 2010-2011 Master Dissertation: English Literature Promotor: Prof. Dr. Stef Craps Table of Contents Foreword p.4 Introduction p.5 Chapter 1: The Peculiar Genesis of What Is the What p.10 1.1 A form characterized by a remarkable collaboration p.10 1. 2 An Autobiography….And a Novel p.11 1.2.1 Consequences of the Miscellaneous Form p.14 1. 3 Broadening the subject p.15 Chapter 2: What Is the What’s Goals p.17 2.1 What Is the What ’s Preface and the Notion of the “Addressee” p17 2.2 An Analysis of the “Addressees” p.20 2.2.1 Valentino and TV Boy: Diminishing and Growing Distance p.20 2.2.2 The Christian Neighbours and the Police: Two “Lost Addressees” p.26 2.2.3 Reaching out for Julian , p.27 2.2.4 The People From the Gym: Keeping Up Appearances? p.30 2.3 What Is the What ’s Last Chapter p.32 Chapter 3: Valentino’s Flight: Coping With Atrocities p. 34 3.1 The Loss of Valentino’s Mother as His Primary Trauma, p.34 3.1.1 From His Mother’s Arms into the Civil War p.34 3.1.2 Ambiguous Loss p.37 3.1.3 Only One Real Mother p.39 3.2 Valentino’s Coping Strategies p.40 3.2.1 The Lost Boys as Valentino’s Support: Finding and Losing hope p.41 3.2.1.1 Deng p.41 3.2.1.2 William K, the Storyteller of Hope p.43 3.2.2 Valentino’s Faith p.44 2 Chapter 4: The U.S. -

Cognotes Midwinter Meeting & Exhibits February 9–13, 2018 JANUARY PREVIEW | DENVER

COGNOTES MIDWINTER MEETING & EXHIBITS February 9–13, 2018 JANUARY PREVIEW | DENVER DENVER, CO AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Activists Patrisse Cullors, Marley Dias to Open the 2018 ALA Midwinter Meeting & Exhibits arley Dias, the girl- NAACP History Maker – and wonder who started she’s been invited to the White Mthe #1000black- House. Her appearance is girlbooks Campaign, inter- sponsored by Macmillan. views Patrisse Cullors, co- Dias made headlines as a founder of the Black Lives Mat- sixth grader, when she start- ter movement, to learn what de- ed the #1000blackbirlbooks termining factors and mindset Campaign to collect and do- led each of these activists and nate 1,000 books that featured motivated them to take ac- black girls as the main charac- tion. Discover these answers ters. She realized that she saw and more when two genera- no characters like herself in tions tackle issues of inequality the books she was reading and and strive for grassroots level wanted to make a difference. solutions. The Opening Ses- And a difference she has made sion will take place on Friday, with a campaign that has, to Elizabeth Acevedo February 9 from 4:00 – 5:15 Marley Dias Patrisse Cullors date generated more than (Photo by Curtis Moore) p.m. at the ALA Midwinter (Photo by Andrea Cipriani Mecchi) 10,000 books. She has been Author and Meeting. memoirs, Cullors co-wrote When They Call featured in the New York Times and was recog- Poet, Elizabeth Cofounder of Black Lives Matter, Cul- You A Terrorist with journalist asha bandele. nized as a “21 under 21” Ambassador for Teen lors is an artist, freedom fighter and perfor- The book, with a foreword by activist Angela Vogue. -

Read Ebook \\ a Hologram for the King (Paperback) \ 0JHKJI0DPZ0U

3DKRLNTHNLZN Kindle # A Hologram for the King (Paperback) A Hologram for th e King (Paperback) Filesize: 5.02 MB Reviews An incredibly amazing book with perfect and lucid information. I was able to comprehended everything using this written e ebook. I realized this book from my dad and i advised this ebook to understand. (Hank Ruecker DDS) DISCLAIMER | DMCA JNDHXRFQW9FV Doc // A Hologram for the King (Paperback) A HOLOGRAM FOR THE KING (PAPERBACK) To get A Hologram for the King (Paperback) eBook, please refer to the web link under and save the document or have access to other information which might be related to A HOLOGRAM FOR THE KING (PAPERBACK) book. Penguin Books Ltd, United Kingdom, 2013. Paperback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book. New from Dave Eggers, National Book Award finalist A Hologram for the King.In a rising Saudi Arabian city, far from weary, recession-scarred America, a struggling businessman pursues a last-ditch attempt to stave o foreclosure, pay his daughter s college tuition, and finally do something great. In A Hologram for the King, Dave Eggers takes us around the world to show how one man fights to hold himself and his splintering family together in the face of the global economy s gale-force winds. This taut, richly layered, and elegiac novel is a powerful evocation of our contemporary moment - and a moving story of how we got here.Praise for A Hologram for the King: Absorbing . modest and equally satisfying: the writing of a comic but deeply aecting tale about one man s travails that also provides a bright, digital snapshot of our times Michiko Kakutani, New York Times A fascinating novel New Yorker A spare but moving elegy for the American century Publishers Weekly Eggers understands the pressures of American downward-mobility, and in the protagonist of his novel, Alan Clay, has created an Everyman, a post-modern Willy Loman . -

The Monk of Mokha by Dave Eggers Knopf Canada; 327 PP; $36

What's up with Dave Eggers 'novelizing' the stories of others? David Hayes: Eggers conducted hundreds of hours of interviews, but this time he's written a conventional biography in the third The Monk of Mokha By Dave Eggers Knopf Canada; 327 PP; $36 Book Review by David Hayes, February 22, 2018, The National Post Dave Eggers is an eclectic literary figure, an experimenter, an impresario and an activist with a progressive agenda. He emerged in 1994 as co-founder of Might, a satirical magazine loved by cool 20-somethings who nevertheless weren’t a large or rich enough readership to sustain it. It died in 1997, but three years later, Eggers published his first book, the bestselling A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. Ostensibly a memoir about Eggers bringing up his eight-year-old brother after their parents died of cancer, it was anything but conventional. Filled with fantasy sequences and stream-of-consciousness narration, it included a 40-plus page preface with a chart, footnotes and helpful advice for reading the book, including “…many of you might want to skip much of the middle section, namely pages 239- 351, which concern the lives of people in their early 20s, and those lives are very difficult to make interesting…” Eggers also merrily admitted that some of the content was fictionalized. That self-consciously post-modern approach made Eggers a celebrity, and he has gone on to write more than a dozen books (both fiction and non-fiction) and several screenplays, as well as launching the celebrated literary journal McSweeney’s, and creating the literacy non-profit 826 Valencia and the social justice non-profit Voice of Witness.