Beyond 'Literacy Crusading': Neocolonialism, the Nonprofit Industrial Complex, and Possibilities of Divestment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dave Eggars Press Release

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE Contacts: Jon Newman SEPTEMBER 12, 2007 (804) 788-1414 Russ Martz (412) 497-5775 Author and Founder of Children’s Writing Laboratories Honored with $250,000 Heinz Award for Arts and Humanities Youngest-ever recipient Dave Eggers recognized for literary and philanthropic achievements PITTSBURGH, September 12, 2007 – A critically acclaimed novelist whose meteoric commercial success has helped propel him into the worlds of philanthropy, advocacy and education has been selected to receive the 13th annual Heinz Award in the Arts and Humanities, among the largest individual achievement prizes in the world. Dave Eggers of San Francisco, the author of best-selling works in both fiction and nonfiction as well as the founder of inner-city writing laboratories for youth and a publishing house for writers, is among six distinguished Americans selected to receive one of the $250,000 awards, presented in five categories by the Heinz Family Foundation. At age 37, he is the youngest-ever recipient of the Heinz Award. “Dave Eggers is not only an accomplished and versatile man of letters but the protagonist of a real-life story of generosity and inspiration,” said Teresa Heinz, chairman of the Heinz Family Foundation. “As a young man, he has infused his love of writing and learning into the broader community, nurturing the talents and aspirations of a new generation of writers and creating new outlets for a range of literary expression. Whether as a writer, mentor or benefactor, he has provided voice to the value of human potential.” - more - Page 2 of 4 - Heinz Awards, Arts and Humanities Having burst on the literary scene with his autobiographical bestseller, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, before he was 30, Mr. -

ORGANIZATION DESCRIPTION: 826NYC Is a Tutoring and Literacy

ORGANIZATION DESCRIPTION: 826NYC is a tutoring and literacy center dedicated to helping underserved students, ages 6-18, with expository and creative writing, homework, college preparation, and other essential skills. Modeled after 826 Valencia (founded in 2002 by Dave Eggers and Nínive Calegari in San Francisco’s Mission District), 826NYC is located in the Park Slope neighborhood of Brooklyn and is fronted by the world famous Brooklyn Superhero Supply Store. The revenues from the store support 826NYC and its student programming. 826NYCs work is based on the understanding that great leaps in learning can happen with one-on-one attention, and that strong writing skills are fundamental to future success. Through the work of talented staff and the assistance of more than 1,000 volunteers, 826NYC provides after-school tutoring, class field trips, writing workshops, in-schools programs (including special projects and full-time staffing of a writers’ at the Williamsburg Library), journal and book publication, and college preparation—all free of charge. 826NYC is especially committed to supporting teachers and publishing student work. 826 tutoring and literacy centers are in seven other cities—San Francisco, Los Angeles, Ann Arbor, Chicago, Seattle, Boston, and Washington, DC. These eight chapters operate under the umbrella of 826 National, which coordinates the work of the chapters, implements best practices as established by the chapters and the 826 National board, and raises funds to support the work of 826 National and the chapters. 826 was chosen by GOOD Magazine as one of the top 30 companies to work at. 826NYC, the other seven chapters, and 826 National are separate 501(c)(3) organizations with their own boards of directors. -

Los Angeles Times 826 Brings Reading, Writing and Robots to Echo

Los Angeles Times: 826 brings reading, writing and robots to Echo Park 1/8/08 3:12 PM http://www.latimes.com/features/books/la-et-eggers31dec31,0,7374625.story?coll=la-books-headlines From the Los Angeles Times BOOK NEWS 826 brings reading, writing and robots to Echo Park A time-travelers' convenience store? Must be a new literacy center from author Dave Eggers' crew. By Steffie Nelson Special to The Times December 31, 2007 At the grand opening of the Echo Park Time Travel Mart on Dec. 15, the Robot Emotions were going like hot cakes (happiness and schadenfreude were the top sellers). The mystery product Chubble, on the other hand, available in more than 50 different varieties, wasn't really moving. A worker dressed like a cowboy shrugged. "It's really hot in the future." There were also bottles of optimism and socialism, dinosaur eggs, woolly mammoth chili, a bag of shade, a King Tut action figure and all manner of head wear, tri-corner hats as well as bonnets. Fortunately, it was a chilly night, because the slushie machine was on the blink. "Out of order. Come back yesterday," read the handwritten sign. This convenience store for time travelers, whose motto is "Whenever you are, we're already then," is the whimsical retail component of the new Echo Park 826LA, a free literacy and writing center for kids that was started by author Dave Eggers in San Francisco and then spun off in New York; Chicago; Ann Arbor, Mich.; Seattle; and Boston. Located on a busy stretch of Sunset Boulevard and scheduled to open for drop-in tutoring Jan. -

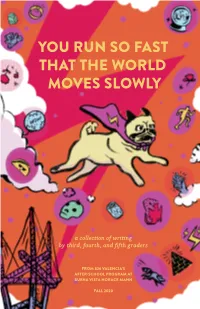

You Run So Fast That the World Moves Slowly

YOU RUN SO FAST THAT THE WORLD MOVES SLOWLY a collection of writing by third, fourth, and fifth graders FROM 826 VALENCIA’S AFTER-SCHOOL PROGRAM AT BUENA VISTA HORACE MANN FALL 2020 YOU RUN SO FAST THAT THE WORLD MOVES SLOWLY BUENA VISTA HORACE MANN AFTER-SCHOOL PROGRAM FALL 2020 PROGRAM LEADS Diana Garcia Ashley Smith OTHER PROGRAM STAFF Emilia Rivera Arel Wiederholt Kassar INTERNS & TUTORS Saffron Agrawal Darren Lee Luis Sepulveda Jason Baum Selina Lee Kano Umezaki Tyler Beneke Masani Limutau Aaliyah Williams Matthew Bussa Noa Mendoza Anne Wong Claire Ewers Rose Mitchell Billie Zeng Emilia Fernandez Claire "Tomi" Osawa Yuli Zhang Hung Ella Gardner Natalia Quesada Marshall Maura Kealey Opal Jane Ratchye SCHOOL PARTNERS BVHM Teachers and Staff COVER ILLUSTRATION Montana Manalo COPY EDITOR James O'Hagan MISSION TENDERLOIN MISSION BAY 826 Valencia St. 180 Golden Gate Ave. 1310 4th St. San Francisco, CA San Francisco, CA San Francisco, CA 94110 94102 94158 826valencia.org Published December 2020 by 826 Valencia. Copyright © 2020 by 826 Valencia. The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and the authors’ imaginations, and do not reflect those of 826 Valencia. We support student publishing and are thrilled that you’ve picked up this book! 826 Valencia and its free programs are fueled by generous contributions from companies, organizations, government agencies, and individuals who provide more than 95% of our budget. 826 Valencia’s partnership with Buena Vista Horace Mann K-8 and this publication are made possible in part by support from the Dow Jones Foundation, GGS Foundation, Fleishhacker Foundation, Hellman Foundation, Jamestown Community Center, Marky A. -

Brooklyn Secret

MICHELLE YOUNG AND AUGUSTIN PASQUET SECRET BROOKLYN JONGLEZ PUBLISHING JONGLEZ PUBLISHING TO THE NORTH: DOWNTOWN BROOKLYN LONG ISLAND UNIVERSITY 19 owntown Brooklyn, around the intersection of Flatbush Avenue BASKETBALL COURT Dand Fulton Street, was hailed as the “Times Square of Brooklyn,” by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1928. This was the year that the Paramount Theatre was under construction. The accompanying map showed 12 A gym inside a historic movie theater theaters all within a few blocks, and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle called it 161 Ashland Place the “Hub of the Largest Theatre District in the world, excepting only Brooklyn, NY 11201 New York.” When the Paramount opened on November 23rd, 1928, Transport: B/Q/R to DeKalb Avenue the total combined capacity of the theaters in this area was 25,000 seats. The opening was such an important one that local businesses, such as Loeser’s department store and Joe’s Restaurant, took out advertisements to welcome the new venue. In addition to movies, the Paramount hosted famous performers like Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington and Frank Sinatra. Downtown Brooklyn has regained some of its entertainment cred with the arrival of the Barclays Center, the addition of BRIC Arts|Media House, and the continued excellence of the Brooklyn Academy of Music. But many of the old theaters are gone. One notable exception lies hidden inside the Long Island University Athletic Center. The basketball court sits amid an opulent backdrop, the auditorium of the former Paramount Theatre. The scoreboard sits in front of the grand stage proscenium and the original details of the theater are well preserved on the ornamented walls and arched, latticed ceiling. -

Press Kit.Indd

SAN FRANCISCO NEW YORK LOS ANGELES ANN ARBOR/DETROIT CHICAGO BOSTON WASHINGTON DC 826 National is an award-winning network of nonprofit organizations dedicated to providing under-resourced students, ages 6 to 18, with opportunities to explore their creativity and improve their writing skills. All of our programs are free of charge and serve students in and out of school. Our mission is based on the understanding that great leaps in learning can happen with one-on-one attention, and that strong writing skills are fundamental to future success. COMMITMENT TO LITERACY THE 826 National chapters provide students with high-quality, engaging, and hands-on literary arts programs that empower them to develop their creative and expository writing skills. 826 From personal narratives to poetry, our students engage in interdisciplinary learning, using MODEL writing and creativity to enrich and expand upon their studies in school. PROJECT-BASED LEARNING Students become published authors as they see their writing progress from a draft to a recorded song, performed screenplay, or professionally-bound book. 826 National’s chapters publish hundreds of pieces of student writing, celebrating their hard work and showcasing the result. In the process, students are placed in decision-making roles, developing critical thinking skills as they collaborate with instructors and peers. TEACHER & CLASSROOM SUPPORT Our goal is to be a resource to teachers through field trips to our writing centers, in-school programs, and specialized workshops. Bringing our programs to the classroom directly supports teachers as they inspire their students to write. VOLUNTEER & COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT Our chapters are vital and vibrant parts of their communities. -

Writing Centers Seek to ...Tivity

1/23/2015 Writing Centers Seek to Unlock Youths' Creativity - Education Week Published Online: June 10, 2014 Published in Print: June 11, 2014, as Writing Centers Seek to Unlock Creativity Writing Centers Seek to Unlock Youths' Creativity By Liana Heitin The idea of going to an afterschool tutoring center is undoubtedly groaninducing for most students. But what if they could enter the workspace through a secret door? And what if that secret door were located in the back of a store that sold supplies for superheroes— capes, truth serum, photon shooters, and invisibility detection goggles? A nonprofit organization called 826 National, co founded by author Dave Eggers and educator Nínive Calegari, now has eight such tutoring centers in urban areas around the country, each with a unique retail storefront that supports the free programming and is designed to fire up students' imaginations. The centers— all focused on creative writing—offer workshops, oneon one homework help, field trips, inschool support for teachers, and summer sessions. They're staffed mainly by community volunteers. The national network, which started with a single center at 826 Valencia Street in San Francisco 12 years ago, now reaches 30,000 students—a majority of whom are from underresourced communities. Partly because of the star power of Mr. Eggers, the author of the bestselling memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, the network has attracted a steady stream of volunteers and some celebrity attention. It's also continuing to expand across the country, and possibly internationally. The newest chapter, opened in 2010 in Washington, has quickly ramped up and now serves some 3,300 youths. -

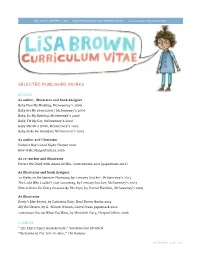

Selected Published Works

912 COLE912 S TREETCOLE S#TREET 331 . S#AN 331 F RANCISCO. SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA CALIFORNIA 94117 . (415)94117 682-7591 . www.americanchickens.com . [email protected] SELECTED PUBLISHED WORKS BOOKS As author, illustrator and book designer Baby Plan My Wedding, McSweeney’s 2009 Baby Get Me Some Lovin’, McSweeney’s 2009 Baby, Do My Banking, McSweeney’s 2006 Baby, Fix My Car, McSweeney’s 2006 Baby Mix Me a Drink, McSweeney’s 2005 Baby Make Me Breakfast, McSweeney’s 2005 As author and illustrator Vampire Boy’s Good Night, Harper 2010 How to Be, HarperCollins 2006 As co-author and illustrator Picture the Dead, with Adele Griffin, Sourcebooks 2011 (paperback 2012) As illustrator and book designer 29 Myths on the Swinster Pharmacy, by Lemony Snicket, McSweeney’s 2014 The Latke Who Couldn’t Stop Screaming, by Lemony Snicket, McSweeney’s 2007 How to Dress For Every Occasion By The Pope, by Daniel Handler, McSweeney’s 2005 As illustrator Emily’s Blue Period, by Cathleen Daly, Neal Porter Books 2014 Alif the Unseen, by G. Willow Wilson, Grove Press paperback 2012 Sometimes You Get What You Want, by Meredith Gary, HarperCollins 2008 COMICS “The Three Panel Book Review,” San Francisco Chronicle “Welcome to the Ten-in-One,” The Rumpus LISA BROWN . page 1 of 3 articles “Picture It” NYT Sunday Book Review, December 8, 2013 “Tastes of Victory:‘Valentine and His Violin,’ and More” NYT Sunday Book Review, November 9, 2012 “Lions and Hippos and Whales, Oh My!” NYT Sunday Book Review, November 13, 2011 antholoGIES Who Done It? ed. -

By 2030, Every Under-Resourced Student in San

Dear friends, It is with great pride that we share how much you have helped 826 Valencia accomplish over the last year. With your support, we have served over 9,000 students in San Francisco and opened our third center as an anchor service in an affordable housing building for families in Mission Bay. What’s more, we engaged in a strategic planning process that helped us reflect on our rapid scaling these past six years and focus on our plans for the future. Photo by William Mercer McLeod As part of this process, we asked ourselves critical questions. What is our biggest, most audacious goal? In other words, what kind of community are we trying to create for our students, in our city, and in our world? And what is the role of writing in our lives? These questions led us to reflect on what makes our model successful, and how to leverage it to support more students more deeply. We examined how our programs transform our students’ relationships to writing, how to amplify their voices to an even wider audience, and how we can support our people (staff, volunteers, and board) to be effective allies for our youth. As we reflected, it was amazing to see our stakeholders talk and write about their ideas, and then take action! I realized that this is the power of writing—as we write and share, we are emboldened to act on things that matter to us. We see ABOUT US evidence of this every day in the young people we serve. -

The Monk of Mokha by Dave Eggers Knopf Canada; 327 PP; $36

What's up with Dave Eggers 'novelizing' the stories of others? David Hayes: Eggers conducted hundreds of hours of interviews, but this time he's written a conventional biography in the third The Monk of Mokha By Dave Eggers Knopf Canada; 327 PP; $36 Book Review by David Hayes, February 22, 2018, The National Post Dave Eggers is an eclectic literary figure, an experimenter, an impresario and an activist with a progressive agenda. He emerged in 1994 as co-founder of Might, a satirical magazine loved by cool 20-somethings who nevertheless weren’t a large or rich enough readership to sustain it. It died in 1997, but three years later, Eggers published his first book, the bestselling A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. Ostensibly a memoir about Eggers bringing up his eight-year-old brother after their parents died of cancer, it was anything but conventional. Filled with fantasy sequences and stream-of-consciousness narration, it included a 40-plus page preface with a chart, footnotes and helpful advice for reading the book, including “…many of you might want to skip much of the middle section, namely pages 239- 351, which concern the lives of people in their early 20s, and those lives are very difficult to make interesting…” Eggers also merrily admitted that some of the content was fictionalized. That self-consciously post-modern approach made Eggers a celebrity, and he has gone on to write more than a dozen books (both fiction and non-fiction) and several screenplays, as well as launching the celebrated literary journal McSweeney’s, and creating the literacy non-profit 826 Valencia and the social justice non-profit Voice of Witness. -

What Features Does It Share with Classic Works Like Ho

Reading Group Discussion Questions—What is the What 1. In what ways can What Is the What be understood as a hero’s journey? What features does it share with classic works like Homer’s Odyssey and Virgil’s Aeneid or more modern works like Richard Wright’s Black Boy and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road? What are the most significant features of Valentino’s journey? In what ways is Valentino’s story both unique and universal? 2. When he is in the United States, Valentino says that he wants everyone to hear his stories. “Written words are rare in small villages like mine, and it is my right and obligation to send my stories into the world, even if silently, even if utterly powerless” [p. 29]. Through Eggers, Valentino has found a way to send his stories into the world. Are they powerless to alter the suffering he and his fellow Sudanese have endured? What powers do they possess? 3. What are Valentino’s most appealing qualities—as a character in his own story and as a narrator of that story? 4. What is the significance of Valentino addressing his stories to people who aren’t listening—to Michael, TV Boy, to Julian, the intake person at the hospital, to members of his gym, etc.? Why would Eggers make this narrative choice? 5. Why is a personal story—Valentino’s story—of the violence and oppression in Sudan more valuable than any purely historical account could be? What emotions does Valentino’s story arouse that a more objective treatment could not? 6. -

A Novel, by Dave Eggers

- Wednesday Evening, December 10, 2014 at 7:00 P.M. Monday Afternoon, December 15, 2014, at 1:00 P.M. The Circle: A Novel, by Dave Eggers Discussion Leader: Ellen Getreu Hired to work for the Circle, the world's most powerful internet company, Mae Holland begins to question her luck as life beyond her job grows distant, a strange encounter with a colleague leaves her shaken, and her role at the Circle becomes increasingly public. What begins as the captivating story of one woman’s ambition and idealism soon becomes a heart-racing novel of suspense, raising questions about memory, history, privacy, democracy, and the limits of human knowledge. Monday, January 12, 2015, at 3:00 P.M. (please note later time) Fever: A Novel, by Mary Beth Keane Discussion Leader: Edna Ritzenberg The story of Mary Mallon, known as “Typhoid Mary,” who came to New York in 1883 and cooked for the wealthy families of Manhattan. “Fever manages to rescue a demonized woman from history and humanize her brilliantly. Mary Beth Keane brings to light a moving love story behind the headlines, and she carries the reader forward with such efficiency, you will hardly notice how graceful are her sentences and how entwined you have become with this fascinating, heartbreaking story.”(Billy Collins) Discussion Guide for The Circle ‘THE CIRCLE’ BY DAVE EGGERS By Jane Ciabattari, www.bostonglobe.com, October 19, 2013 When I finished reading Dave Eggers's chilling and caustic novel, "The Circle," I felt like disconnecting from all my online devices and retreating for a while into an unplugged world.