Color of the Sea ���� ����������������������������

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A a C P , I N C

A A C P , I N C . Asian Am erican Curriculum Project Dear Friends; AACP remains concerned about the atmosphere of fear that is being created by national and international events. Our mission of reminding others of the past is as important today as it was 37 years ago when we initiated our project. Your words of encouragement sustain our efforts. Over the past year, we have experienced an exciting growth. We are proud of publishing our new book, In Good Conscience: Supporting Japanese Americans During the Internment, by the Northern California MIS Kansha Project and Shizue Seigel. AACP continues to be active in publishing. We have published thirteen books with three additional books now in development. Our website continues to grow by leaps and bounds thanks to the hard work of Leonard Chan and his diligent staff. We introduce at least five books every month and offer them at a special limited time introductory price to our newsletter subscribers. Find us at AsianAmericanBooks.com. AACP, Inc. continues to attend over 30 events annually, assisting non-profit organizations in their fund raising and providing Asian American book services to many educational organizations. Your contributions help us to provide these services. AACP, Inc. continues to be operated by a dedicated staff of volunteers. We invite you to request our catalogs for distribution to your associates, organizations and educational conferences. All you need do is call us at (650) 375-8286, email [email protected] or write to P.O. Box 1587, San Mateo, CA 94401. There is no cost as long as you allow enough time for normal shipping (four to six weeks). -

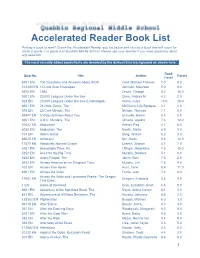

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Picking a book to read? Check the Accelerated Reader quiz list below and choose a book that will count for credit in grade 7 or grade 8 at Quabbin Middle School. Please see your teacher if you have questions about any selection. The most recently added books/tests are denoted by the darkest blue background as shown here. Book Quiz No. Title Author Points Level 8451 EN 100 Questions and Answers About AIDS Ford, Michael Thomas 7.0 8.0 101453 EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 5.0 9.0 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George 8.2 16.0 9201 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Clare, Andrea M. 4.3 2.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 6651 EN 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague 4.1 2.0 593 EN 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa 7.1 8.0 59347 EN 5 Ways to Know About You Gravelle, Karen 8.3 5.0 8851 EN A.B.C. Murders, The Christie, Agatha 7.6 12.0 81642 EN Abduction! Kehret, Peg 4.7 6.0 6030 EN Abduction, The Newth, Mette 6.8 9.0 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William 6.2 3.0 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth 6.6 16.0 11577 EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 4.7 7.0 5251 EN Acceptable Time, An L'Engle, Madeleine 7.5 15.0 5252 EN Ace Hits the Big Time Murphy, Barbara 5.1 6.0 5253 EN Acorn People, The Jones, Ron 7.0 2.0 8452 EN Across America on an Emigrant Train Murphy, Jim 7.5 4.0 102 EN Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 8.9 11.0 6901 EN Across the Grain Ferris, Jean 7.4 8.0 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon 17602 EN Gregory, Kristiana 5.5 4.0 Trail Diary.. -

Living Voices Within the Silence Bibliography 1

Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 1 Within the Silence bibliography FICTION Elementary So Far from the Sea Eve Bunting Aloha means come back: the story of a World War II girl Thomas and Dorothy Hoobler Pearl Harbor is burning: a story of World War II Kathleen Kudlinski A Place Where Sunflowers Grow (bilingual: English/Japanese) Amy Lee-Tai Baseball Saved Us Heroes Ken Mochizuki Flowers from Mariko Rick Noguchi & Deneen Jenks Sachiko Means Happiness Kimiko Sakai Home of the Brave Allen Say Blue Jay in the Desert Marlene Shigekawa The Bracelet Yoshiko Uchida Umbrella Taro Yashima Intermediate The Burma Rifles Frank Bonham My Friend the Enemy J.B. Cheaney Tallgrass Sandra Dallas Early Sunday Morning: The Pearl Harbor Diary of Amber Billows 1 Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 2 The Journal of Ben Uchida, Citizen 13559, Mirror Lake Internment Camp Barry Denenberg Farewell to Manzanar Jeanne and James Houston Lone Heart Mountain Estelle Ishigo Itsuka Joy Kogawa Weedflower Cynthia Kadohata Boy From Nebraska Ralph G. Martin A boy at war: a novel of Pearl Harbor A boy no more Heroes don't run Harry Mazer Citizen 13660 Mine Okubo My Secret War: The World War II Diary of Madeline Beck Mary Pope Osborne Thin wood walls David Patneaude A Time Too Swift Margaret Poynter House of the Red Fish Under the Blood-Red Sun Eyes of the Emperor Graham Salisbury, The Moon Bridge Marcia Savin Nisei Daughter Monica Sone The Best Bad Thing A Jar of Dreams The Happiest Ending Journey to Topaz Journey Home Yoshiko Uchida 2 Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 3 Secondary Snow Falling on Cedars David Guterson Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet Jamie Ford Before the War: Poems as they Happened Drawing the Line: Poems Legends from Camp Lawson Fusao Inada The moved-outers Florence Crannell Means From a Three-Cornered World, New & Selected Poems James Masao Mitsui Chauvinist and Other Stories Toshio Mori No No Boy John Okada When the Emperor was Divine Julie Otsuka The Loom and Other Stories R.A. -

Year of Ursula Book List

The 2020 NEA Big Read When the Emperor Was Divine by Julie Otsuka Reading List Fiction No-No Boy – John Okada, (1956) This 1956 novel, by Seattle native John Okada, is considered the first Japanese American novel and an Asian American literary classic. Its title comes from the answers many Japanese Ameri- can men gave to a government questionnaire administered during World War II: would they serve in the armed forces and would they swear loyalty to the U.S. Snow Falling on Cedars – David Guterson (1994) This novel, set on a fictional island in Washington’s Puget Sound, has at its heart an interracial love triangle that includes two Japanese Americans sent to an internment camp. The book won a PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction and was made into an Oscar-nominated film and a play, which Portland Center Stage produced in 2010. What the Scarecrow Said – Stewart David Ikeda (1996) Novel centering on William Fujita, a successful Nisei nursery owner before the war as he tries to rebuild his life in New England after camp having lost both his son and wife in the war. Dis- patched to start a small farming operation for a widowed nurse in the small Quaker town of Juggeston in late 1944, Fujita navigates the tricky politics of the area, while tying up loose ends of his former life. Why She Left Us – Rahna Reiko Rizzuto (1999) Emi Okada finds herself incarcerated at Santa Anita and Amache with two young children and no husband. The story is told in the first person voices of four different characters—none of whom are Emi—who each know only part of the story. -

Terminal Islander Club, by LYNDA LIN a Contingency of Mostly Nisei Bound Assistant Editor by a Shared History and Geography

Anti-Asian Flyer Spring Campaign Eggrolls Etc. in Arizona It's not too late to donate. continues to stand by its Help the PC. continue to racist menu even as APA develop its popular Web site. groups protest. COUPON PAGE 2 NATIONAL PAGE 3 Dice-K Who? CITIZEN Okajima makes an sfnce1929PACIFIC unexpected impact as Boston Red Sox reliever. The National Publication of the Japanese American Citizens League MEMORIAL DAY Shock Jocks ~!~~~~~!!_ M~~~~ ~ dep~~~e~:~~M:}n~l=ra=q~a~n=d..,............A_b_r_o_a--,d Dropped Over erans this Memorial Day, Iraq. For the past four months wishes you had." As ian SIu rs these soldiers are proud to Ishikata has been stationed ' in Ishikata's. life be serving their country. Baghdad overseeing the translation now consists of By Associated Press and P.e. Staff of captured documents and media to seven-day . work NEW YORK-One month after assist the commanders in locating weeks that often last By CAROLINE AOYAGI-STOM the firing of radio host Don Imus for insurgents. 16 hours a day. Executive Editor broadcasting sexist and racist gibes, "As a leader, I felt it was impor- Some days there are a pair of suspended New York shock tant for me to have this experience so briefings with his Lt. Col. George Ishikata has 23 jocks have been permanently pulled that I could understand-my soldiers higher-ups, on other. years of U.S. Army experience from the air by CBS Radio for a better, and so they cO,-!ld feel com- days there's the under his belt. -

Visual Timeline 34

DAY 6–7 Visual Timeline 34 Objectives Weedflower Reading, Discussion Questions, and Journal Prompt • Students will develop an understanding of a chronol- ogy of events related to the Japanese American experi- • On Day 6, read Chapters 9 and 10 (11½ pages) of ence during World War II. Weedflower. • Students will distinguish between actual historical • Continue to add to Handout 2-1: Character events and author-created events. Web Graphic Organizer. • Students will accurately represent events for a visual • Discuss the following question as a class or timeline. in small groups: • What is the mood of people as they are Guiding Questions selling off their possessions and boarding buses? Why? • What are important events in United States history in • Provide a journal prompt for students to 1941 and 1942? respond to: • What are important events in the story of Weedflower • What would be the one thing you would (up to current reading)? take if you and your family were forced to leave your home? Draw a picture of the Assessment(s) object and write four to five sentences • Teacher observation of students’ completed Visual explaining your choice. Timelines. • On Day 7, read Chapters 11 and 12 (12 pages) of Weedflower. Materials • Continue to add to Handout 2-1: Character • Two large sheets of paper for recording student com- Web Graphic Organizer. ments • Discuss the following question as a class or • 4-x-6-inch pieces of white construction paper to use in small groups: as “event cards” to represent timeline events (one per • As Sumiko’s family arrives at the assembly student) center (racetrack), how has her daily life • Student copies of “Timeline for Japanese Americans changed? (Refer to Day 4.) in New Mexico,” included in this unit’s introductory materials and also available for download at http:// Overview www.janm.org/EC-NM-Essay-Timeline.pdf/ (accessed September 6, 2009) In this two-day lesson, students will share their under- • Handout 7-1: Timeline Strips (optional) standing of historical and story events. -

Weedflower 12

LESSON 3 Weedflower 12 Overview Essential Question Upon completion of the first two lessons in the “A • What is our responsibility to make sure we respect all Friend to All” unit, students should have adequate people? background knowledge regarding the historical context of the Japanese American incarceration. Guiding Questions This third and final lesson provides an in-depth • What is a friend? look into the unique circumstances surrounding • How should we treat all people, even if they aren’t the Arizona camps; that is, their placement on friends? Native American reservation lands. The chapter • What is wrong with judging people based on race, book Weedflower, provides a fictional “case study” of religion, and culture? the conflict, cooperation, and eventual friendship that evolves between a Mohave boy and a young Arizona State Standards Japanese American girl sent to the Poston Camp Social Studies—Grade 4 on the Colorado River Indian Reservation. Lesson activities are designed to help students build essential Strand 1: American History vocabulary, describe main events and characters in Concept 8: Great Depression and World War II a story, compare and contrast characters in literary • PO 2. Describe the reasons (e.g., German and selections, and interpret the moral of literary pieces Japanese aggression) for the U.S. becoming involved via a written and illustrated literary response poster. in World War II. • PO 3. Describe the impact of World War II on Arizona Objectives (e.g., economic boost, military bases, Native American and Hispanic contributions, POW camps, relocation Students will be able to: of Japanese Americans). • Use a dictionary to learn the meaning and other • PO 4. -

Journal of Ben Uchida: Citizen 13559 Is a Reinforcing a Text Or Part of a Text

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS? 1 See our online, interactive AAG for even more content, such as... Washington state K-12 learning standards Reading Standards for Informational Text (For these standards, the articles in this AAG Social English would serve as the “text.”) • Key Ideas and Details Studies Example - RI.4.3: Explain events, Language procedures, ideas, or concepts in a EALR 1: CIVICS historical, scientific, or technical text, The student understands and including what happened and why, based applies knowledge of government, law, politics, Arts on specific information in the text. and the nation’s fundamental documents to make decisions about local, national, and • Craft and Structure international issues and to demonstrate Example - RI.4.5: Describe the overall Reading Standards for Literature thoughtful, participatory citizenship. structure (e.g., chronology, comparison, (The following standards assume the script of cause/effect, and problem/solution) of • Component 1.1: Understands key the play as the text – in some cases the book The events, ideas, concepts, or information in ideals and principles of the United Journal of Ben Uchida: Citizen 13559 is a reinforcing a text or part of a text. States, including those in the text for these standards.) • Integration of Knowledge and Ideas Declaration of Independence, the • Key Ideas and Details Constitution, and other fundamental Example - RL.4.3: Describe in depth a RI.4.7: Interpret information documents. Click on an articlecharacter, tosetting, or event in a story or link to it: presented visually, orally, or drama, drawing on specific details in the quantitatively (e.g., in charts, graphs, • 1.1.1 Understands the key ideals of text (e.g., a character’s thoughts, words, diagrams, time lines, animations, or unity and diversity. -

Supplemental Reading Suggestions: Children Baseball Saved Us By

Supplemental Reading Suggestions: Children Baseball Saved Us By Ken Mochizuki This moving illustrated book depicts a Japanese American father and son trying to maintain normalcy during their internment by building a baseball diamond and starting a league. The Bracelet By Yoshiko Uchida When Emi’s family is moved to an internment camp, she is forced to leave her home as well as her best friend Laurie. Laurie gives Emi a bracelet to remember her by, but when Emi loses it, she fears she will also lose the memories of her friend. Children of Manzanar Edited by Heather C. Lindquist This collection of photographs captures the experiences of the nearly 4,000 children and teens imprisoned at the infamous Manzanar War Relocation Center. The photographs, contributed by several photographers including Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams and Toyo Miyatake, are accompanied by quotes from these children, many of whom are now in their 80s and 90s and still vividly remember this dark chapter of their childhood. The Children of Topaz: The Story of the Japanese-American Internment Camp By Michael O. Tunnell & George W. Chilcoat A nonfiction book based on the diary kept by a teacher’s third grade class at an internment camp, this book includes both diary entries and interpretations expanding on the children’s first-hand accounts. Erika-san By Allen Say As a little girl, Erika becomes fascinated by a picture of a rural Japanese house. Her determination to live there brings her to Japan as a young adult and opens her to a beautiful adventure in a place she adopts as her home. -

The Enduring Communities Project of Japanese American Experiences in New Mexico During World War II and Beyond

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Language, Literacy, and Sociocultural Studies ETDs Education ETDs 6-25-2010 The ndurE ing Communities Project of Japanese American Experiences in New Mexico during World War II and Beyond: A Teachers Journey in Creating Meaningful Curriculum for the Secondary Social Studies Classroom Diane Ball Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/educ_llss_etds Recommended Citation Ball, Diane. "The ndurE ing Communities Project of Japanese American Experiences in New Mexico during World War II and Beyond: A Teachers Journey in Creating Meaningful Curriculum for the Secondary Social Studies Classroom." (2010). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/educ_llss_etds/4 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Education ETDs at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Language, Literacy, and Sociocultural Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Enduring Communities Project of Japanese American Experiences in New Mexico during World War II and Beyond: A Teacher’s Journey in Creating Meaningful Curriculum for the Secondary Social Studies Classroom BY Diane Leslie Ball B.A., History and Russian Studies, The University of New Mexico, 1984 M.A., Secondary Education, The University of New Mexico, 2002 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Language, Literacy and Sociocultural Studies The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May 2010 DEDICATION To Mom, for the gift of history To Allyson, for the opportunity To Lyn, for the journey iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In any endeavor of this size, the journey to create the dissertation was certainly not a singular act. -

New Mexico Curriculum Units* * Download Other Enduring Community Units (Accessed September 3, 2009)

ENDURING COMMUNITIES New Mexico Curriculum Units* * Download other Enduring Community units (accessed September 3, 2009). Gift of the Dr. and Mrs. Kikuwo Tashiro Family, Japanese American National Museum (98.175.106) All requests to publish or reproduce images in this collection must be submitted to the Hirasaki National Resource Center at the Japanese American National Museum. More information is available at http://www.janm.org/nrc/. 369 East First Street, Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 | Fax 213.625.1770 | janm.org | janmstore.com For project information, http://www.janm.org/projects/ec Enduring Communities New Mexico Curriculum Writing Team Diane Ball Cindy Basye Ella-Kari Loftfield Gina Medina-Gay Lynette K. Oshima Rebecca Sánchez Trish Steiner Photo by Motonobu Koizumi Project Managers Allyson Nakamoto Jane Nakasako Cheryl Toyama Enduring Communities is a partnership between the Japanese American National Museum, educators, community members, and five anchor institutions: Arizona State University’s Asian Pacific American Studies Program University of Colorado, Boulder University of New Mexico UTSA’s Institute of Texan Cultures Davis School District, Utah 369 East First Street Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 Fax 213.625.1770 janm.org | janmstore.com Copyright © 2009 Japanese American National Museum NEW MEXICO Table of Contents 4 Project Overview of Enduring Communities: The Japanese American Experience in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah Curricular Units* 5 Introduction to the Curricular Units 6 A Teacher’s -

Arizona Curriculum Units* * Download Other Enduring Community Units (Accessed September 3, 2009)

ENDURING COMMUNITIES Arizona Curriculum Units* * Download other Enduring Community units (accessed September 3, 2009). Gift of George Teruo Esaki, Japanese American National Museum (96.25.8A) All requests to publish or reproduce images in this collection must be submitted to the Hirasaki National Resource Center at the Japanese American National Museum. More information is available at http://www.janm.org/nrc/. 369 East First Street, Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 | Fax 213.625.1770 | janm.org | janmstore.com For project information, http://www.janm.org/projects/ec Enduring Communities Arizona Curriculum Writing Team Billy Allen Lynn Galvin Jeannine Kuropatkin (not pictured) Karen Leong Toni Loroña-Allen Jessica Medlin Christina Smith Photo by Richard M. Murakami Project Managers Allyson Nakamoto Jane Nakasako Cheryl Toyama Enduring Communities is a partnership between the Japanese American National Museum, educators, community members, and five anchor institutions: Arizona State University’s Asian Pacific American Studies Program University of Colorado, Boulder University of New Mexico UTSA’s Institute of Texan Cultures Davis School District, Utah 369 East First Street Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 Fax 213.625.1770 janm.org | janmstore.com Copyright © 2009 Japanese American National Museum ARIZONA Table of Contents 4 Project Overview of Enduring Communities: The Japanese American Experience in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah Curricular Units* 5 Introduction to the Curricular Units 6 Investigating the Japanese