Discovering Dorothea Lange's Photographs of the Internment Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Friedlander Dog's Best Friend PR March 2019

Andrew Smith Gallery Arizona, LLC. Masterpieces of Photography LEE FRIEDLANDER SHOW TITLE: Dog’s Best Friend Dates: April 27 - June 15, 2019 Artist’s Reception: DATE/TIME: Saturday April 27, 2019 2-4 p.m. “I think dogs are happy because people feed them fancy food, treat them nicely, pedicure and wash them, take them into their homes.” Lee Friedlander Andrew Smith Gallery, in its new location at 439 N. 6th Ave., Suite 179, Tucson, Arizona 85705, opens an exhibit by the eminent American photographer Lee Friedlander. The exhibit, Dog’s Best Friend, contains 18 prints of dogs and their owners, one of Friedlander’s ongoing “pet projects.” Lee and Maria Friedlander will attend the opening on Saturday, April 27, 2019 from 2 to 4 p.m., where the public is invited to visit with America’s most celebrated photographer and view “the dogs.” The exhibit continues through June 15, 2019. Lee Friedlander is one of America’s legendary photographers. Now in his eighties, he still photographs and makes his own prints in the darkroom as he has been doing for 60 years. In the 1950s he began documenting what he called “the American social landscape,” making pictures that showed how the camera sees reality (different from how the eye sees). In his layered compositions, what are normally understood to be separate objects; buildings, window displays, people, cars, etc., are perpetually interacting with reflective, opaque and transparent surfaces that distort, fragment and bring about surprising, often humorous conjunctions. Friedlander has been photographing virtually non-stop these many decades, expanding the vocabulary of such traditional artistic themes as family, nudes, gardens, trees, self-portraits, landscapes, cityscapes, laborers, artists, jazz musicians, cars, graffiti, statues, parks, advertising signs, and animals. -

Ansel Adams by Ross Loeser February 2010

Ansel Adams By Ross Loeser February 2010 Ansel Adams is one of the most fascinating people of the 20th Century… a photography pioneer whose art captured the imagination of millions of ordinary people. Most of the information in this paper is from his autobiography – written in the last five years of his life. I found the book a joy to read. Adams (1902-1984) was born in San Francisco and lived most of his life in that area. For his last 22 years he lived in Carmel Highlands. Some key formative events in his early life were: In 1916, when he was 14, he influenced his family to go on vacation in Yosemite after reading the book, In the Heart of the Sierras by J.M. Hutchens. During that trip, he received his first camera – a Kodak Box Brownie. He returned to Yosemite every year of his life thereafter.1 He was hired as a “darkroom monkey” by a neighbor who operated a photo finishing business in 1917, which enabled him to learn about making photographic prints. As he grew up, one major focus was music – the piano. “By 1923 I was a budding professional pianist…”2 On a bright spring Yosemite day in 1927, Adams made a photograph that was to “change my understanding of the medium.” The picture was of Half Dome, and titled “Monolith, The Face of Half Dome.” The full story is included later in this paper, but, in a nutshell, he captured how he felt about the scene, not how it actually appeared (e.g. -

A a C P , I N C

A A C P , I N C . Asian Am erican Curriculum Project Dear Friends; AACP remains concerned about the atmosphere of fear that is being created by national and international events. Our mission of reminding others of the past is as important today as it was 37 years ago when we initiated our project. Your words of encouragement sustain our efforts. Over the past year, we have experienced an exciting growth. We are proud of publishing our new book, In Good Conscience: Supporting Japanese Americans During the Internment, by the Northern California MIS Kansha Project and Shizue Seigel. AACP continues to be active in publishing. We have published thirteen books with three additional books now in development. Our website continues to grow by leaps and bounds thanks to the hard work of Leonard Chan and his diligent staff. We introduce at least five books every month and offer them at a special limited time introductory price to our newsletter subscribers. Find us at AsianAmericanBooks.com. AACP, Inc. continues to attend over 30 events annually, assisting non-profit organizations in their fund raising and providing Asian American book services to many educational organizations. Your contributions help us to provide these services. AACP, Inc. continues to be operated by a dedicated staff of volunteers. We invite you to request our catalogs for distribution to your associates, organizations and educational conferences. All you need do is call us at (650) 375-8286, email [email protected] or write to P.O. Box 1587, San Mateo, CA 94401. There is no cost as long as you allow enough time for normal shipping (four to six weeks). -

The Curriculum

Intergenerational Digital Photography Workshop Curriculum About this Curriculum With funding from The Brookdale Foundation, Generations United worked with professional photographer, Annie Levy to pilot the intergenerational photography workshop during the summer of 2007 with two organizations in New York – the Carter Burden Center for the Aging and DOROT. This curriculum is based on the lessons learned from the two pilot projects. About Generations United Generations United (GU) is the national membership organization focused solely on improving the lives of children, youth, and older people through intergenerational strategies, programs, and public policies. GU represents more than 100 national, state, and local organization and individuals. Since 1986, GU has served as a resource for educating policymakers and the public about the economic, social, and personal imperatives of intergenerational cooperation. GU acts as a catalyst for stimulating collaboration between aging, children, and youth organizations providing a forum to explore areas of common ground while celebration the richness of each generations. For more information, visit www.gu.org. About Annie Levy Annie Levy is a photographer and creative director who documents, and brings to life, the experience and stories of ordinary people through the art of portraiture in its variety of forms – image/text, exhibit/installation, presentation/performance. With a special focus on the lives of older and young people, she is committed to creating works for both innovative and traditional venues that inspire, educate and influence public opinion and perception. Examples of Ms. Levy’s work have been featured at the United Nations and The Frick Collection for their “Art of Observation” program. -

The Museum of Modern Art Dedicates Erna and Victor Hasselblad Photography Study Center

)** The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART DEDICATES ERNA AND VICTOR HASSELBLAD PHOTOGRAPHY STUDY CENTER October 21, 1985, New York King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden, Officers of the Museum and of the Erna and Victor Hasselblad Foundation, and members of the Museum's Trustee Committee for Photography today were among the guests at the formal dedication of the Erna and Victor Hasselblad Photography Study Center. "Today...is an important day for Sweden and for the Hasselblad Foundation," said Alf Akerman, chairman of the Board of the Hasselblad Foundation. "A new channel has been formed for contacts and a cultural gate has been opened which we hope will be of importance for further development of good relations between our countries." William S. Paley, chairman of the Board of Trustees, The Museum of Modern Art, stated, "We are both grateful and proud that the Hasselblad Foundation has made this extraordinary gift. We are grateful for what it enables our Study Center to do. We are proud of the international recognition it represents. And we are also proud that our Study Center now bears so distinguished a name." Although the Department of Photography has maintained a study center since 1964, its greatly expanded new facility is named in honor of the Hasselblads, as a gesture of gratitude to the Foundation that bears their names. An unprecedented gift from the Foundation will enable the Department of Photography to sustain and expand its capacity for sharing its rare resources and research materials with the larger photography community. John Szarkowski, director of the Department of Photography, has described this community as "an international audience, transcending national or regional perspectives." Since the Department of Photography first made its collection, library, and supporting archives available to the public for study, it has devoted an increasing amount of thought and attention to its study center. -

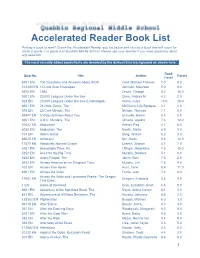

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Picking a book to read? Check the Accelerated Reader quiz list below and choose a book that will count for credit in grade 7 or grade 8 at Quabbin Middle School. Please see your teacher if you have questions about any selection. The most recently added books/tests are denoted by the darkest blue background as shown here. Book Quiz No. Title Author Points Level 8451 EN 100 Questions and Answers About AIDS Ford, Michael Thomas 7.0 8.0 101453 EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 5.0 9.0 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George 8.2 16.0 9201 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Clare, Andrea M. 4.3 2.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 6651 EN 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague 4.1 2.0 593 EN 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa 7.1 8.0 59347 EN 5 Ways to Know About You Gravelle, Karen 8.3 5.0 8851 EN A.B.C. Murders, The Christie, Agatha 7.6 12.0 81642 EN Abduction! Kehret, Peg 4.7 6.0 6030 EN Abduction, The Newth, Mette 6.8 9.0 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William 6.2 3.0 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth 6.6 16.0 11577 EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 4.7 7.0 5251 EN Acceptable Time, An L'Engle, Madeleine 7.5 15.0 5252 EN Ace Hits the Big Time Murphy, Barbara 5.1 6.0 5253 EN Acorn People, The Jones, Ron 7.0 2.0 8452 EN Across America on an Emigrant Train Murphy, Jim 7.5 4.0 102 EN Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 8.9 11.0 6901 EN Across the Grain Ferris, Jean 7.4 8.0 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon 17602 EN Gregory, Kristiana 5.5 4.0 Trail Diary.. -

Living Voices Within the Silence Bibliography 1

Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 1 Within the Silence bibliography FICTION Elementary So Far from the Sea Eve Bunting Aloha means come back: the story of a World War II girl Thomas and Dorothy Hoobler Pearl Harbor is burning: a story of World War II Kathleen Kudlinski A Place Where Sunflowers Grow (bilingual: English/Japanese) Amy Lee-Tai Baseball Saved Us Heroes Ken Mochizuki Flowers from Mariko Rick Noguchi & Deneen Jenks Sachiko Means Happiness Kimiko Sakai Home of the Brave Allen Say Blue Jay in the Desert Marlene Shigekawa The Bracelet Yoshiko Uchida Umbrella Taro Yashima Intermediate The Burma Rifles Frank Bonham My Friend the Enemy J.B. Cheaney Tallgrass Sandra Dallas Early Sunday Morning: The Pearl Harbor Diary of Amber Billows 1 Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 2 The Journal of Ben Uchida, Citizen 13559, Mirror Lake Internment Camp Barry Denenberg Farewell to Manzanar Jeanne and James Houston Lone Heart Mountain Estelle Ishigo Itsuka Joy Kogawa Weedflower Cynthia Kadohata Boy From Nebraska Ralph G. Martin A boy at war: a novel of Pearl Harbor A boy no more Heroes don't run Harry Mazer Citizen 13660 Mine Okubo My Secret War: The World War II Diary of Madeline Beck Mary Pope Osborne Thin wood walls David Patneaude A Time Too Swift Margaret Poynter House of the Red Fish Under the Blood-Red Sun Eyes of the Emperor Graham Salisbury, The Moon Bridge Marcia Savin Nisei Daughter Monica Sone The Best Bad Thing A Jar of Dreams The Happiest Ending Journey to Topaz Journey Home Yoshiko Uchida 2 Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 3 Secondary Snow Falling on Cedars David Guterson Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet Jamie Ford Before the War: Poems as they Happened Drawing the Line: Poems Legends from Camp Lawson Fusao Inada The moved-outers Florence Crannell Means From a Three-Cornered World, New & Selected Poems James Masao Mitsui Chauvinist and Other Stories Toshio Mori No No Boy John Okada When the Emperor was Divine Julie Otsuka The Loom and Other Stories R.A. -

Historic Photogs Presentation 4.Key

& Weegee (Arthur Fellig) A photographer and photojournalist, known for his stark black and white street photography. Weegee worked in Manhattan, New York City's Lower East Side as a press photographer during the 1930s and '40s, and he developed his signature style by following the city's emergency services and documenting their activity. Weegee (Arthur Fellig) Gary Winogrand Gary Winograd was a street photographer from the Bronx, New York, known for his portrayal of American life, and its social issues, in the mid-20th century. Though he photographed in Los Angeles and elsewhere, Winogrand was essentially a New York photographer Gary Winogrand Gordon Parks Parks, born in 1912, was the first African-American photographer hired at Life and Vogue magazines. Focusing on race relations, civil rights, poverty and urban life, his body of work documented controversial aspects of American culture from the early 1940s until his death in 2006. He was a self- taught artist who purchased his first camera at the age of 25. Ansel Adams American photographer and environmentalist. His black-and-white landscape photographs of the American West, especially Yosemite National Park Ansel Adams Manuel Álvarez Bravo Often cited as Mexico's most celebrated fine art photographer, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, whose life almost spanned the entire 20th century, relentlessly captured the history of the country's evolving social and geopolitical atmosphere. His early work was based on European influences, but he was soon influenced by the Mexican muralism movement and the general cultural and political push at the time to redefine Mexican identity. Lola Álvarez Bravo Lola Álvarez Bravo was one of Mexico’s most important photographers. -

Ansel Adams in the Human and Natural Environments of Yosemite

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council --Online Archive National Collegiate Honors Council Spring 2005 Seeing Nature: Ansel Adams in the Human and Natural Environments of Yosemite Megan McWenie University of Arizona, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nchcjournal Part of the Higher Education Administration Commons McWenie, Megan, "Seeing Nature: Ansel Adams in the Human and Natural Environments of Yosemite" (2005). Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council --Online Archive. 161. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nchcjournal/161 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the National Collegiate Honors Council at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council --Online Archive by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Portz-Prize-Winning Essay, 2004 55 SPRING/SUMMER 2005 56 JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL COLLEGIATE HONORS COUNCIL MEGAN MCWENIE Portz Prize-Winning Essay, 2004 Seeing Nature: Ansel Adams in the Human and Natural Environments of Yosemite MEGAN MCWENIE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA allace Stegner once hailed the legacy of Ansel Adams as bringing photography Wto the world of art as a unique “way of seeing.”1 What Adams saw through the lens of his camera, and what audiences see when looking at one of his photographs, does indeed constitute a particular way of seeing the world, a vision that is almost always connected to the natural environment. An Ansel Adams photograph evokes more than an aesthetic response to his work—it also stirs reflections about his involvement in the natural world that was so often his subject. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

An Investigation of Sacred and Mundane Landscapes and the Alchemy of Light

The splendour of the insignificant: An investigation of sacred and mundane landscapes and the alchemy of light Item Type Thesis Authors White-Jackson, Rachel Citation White, R. (2017) 'The splendour of the insignificant: An investigation of sacred and mundane landscapes and the alchemy of light', PhD Thesis, University of Derby Download date 24/09/2021 16:34:20 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10545/621819 UNIVERSITY OF DERBY THE SPLENDOUR OF THE INSIGNIFICANT: AN INVESTIGATION OF SACRED AND MUNDANE LANDSCAPES AND THE ALCHEMY OF LIGHT RACHEL WHITE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2017 1 THE SPLENDOUR OF THE INSIGNIFICANT: AN INVESTIGATION OF SACRED AND MUNDANE LANDSCAPES AND THE ALCHEMY OF LIGHT CONTENTS LIST OF IMAGES 3 PREFACE 13 ABSTRACT 14 INTRODUCTION 16 A WORN OUT AESTHETIC OF PURITY 40 COMMONPLACE BEAUTIES 87 THE SPLENDOUR OF THE INSIGNIFICANT 139 RISKING ENCHANTMENT 197 CONCLUSION: UGLINESS COSTS MORE 245 THE SURFACE GLITTERED OUT OF HEART OF LIGHT 256 BIBLIOGRAPHY 278 2 LIST OF IMAGES Introduction - Rachel White, M6 Toll Road, 2007 Rachel White, Car, 2015 Chapter 1 - A WORN-OUT AESTHETIC OF PURITY Rachel White, Moon, 2016 Ansel Adams, Tetons and Snake River, Grand Teton National Park, 1942 Ansel Adams, Monolith, The Face of Half Dome, Yosemite Valley, 1927 Joe Cornish, Buachaille Etive Mor, Winter, Scotland, (Date unspecified) Thomas Cole, ‘The Oxbow, View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm, 1836 Ansel Adams, Aspens, Northern New Mexico, 1958 -

From the Dust Bowl to Harlem the Arts in Depression-Era America by Dean Schneider

E x p l o r i n g t h e A r t s From the Dust Bowl to Harlem The Arts in Depression-Era America by Dean Schneider hen I think of the Great Depression, the dust bowl first comes to mind; Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, Dorothea Lange’s W“Migrant Mother,” Woody Guthrie wandering the country, guitar slung on his back; an image of grayness, heaviness, and hardscrabble existence. But the 1930s and 1940s were also Harlem, the Cotton Club, the Savoy Ballroom, and the swing era. It was Grant Wood’s American Gothic and his odes to lush land and vibrant Iowa farm life. In short, times were hard, but times were what they always are––full of life, determination, and the impulse to make art, music, and literature. Bonnie Christensen offers an image of folksinger and songwriter Woody Guthrie “strolling / In wheat fields waving” in her book Woody Guthrie. B o o k L i n k s J u n e / J u l y 2 0 0 3 43 What a rich education awaits leap from his pages. Robert Andrew there even was a cultural life in such children who are exposed to the Parker’s Jackson Pollock is captured a difficult time. But just as the New literature, art, and music of that mid-sling. Bill Robinson tap dances Deal government provided jobs and time, including the big band music across the cover of Leo and Diane food and initiatives that changed of Duke Ellington and Benny Dillons’ Rap a Tap Tap.