Dress Codes Ellen Lesperance and Diane Simpson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENGLISH Booklet Accompanying the Exhibition Robes Politiques — Women Power Fashion 19.3.2021– 6.2.2022

ROBES POLITIQUES WOMEN POWER FASHION ENGLISH booklet accompanying the exhibition robes politiques — women power fashion 19.3.2021– 6.2.2022 ern-oriented countries, and in the first half of the 20th century, women fought FEMALE POWER for voting and representation rights in AND POWERLESSNESS many states. A HISTORICAL In the 19th century, Switzerland was con- PERSPECTIVE sidered one of the most progressive de- mocracies. Nonetheless, in 1971, it was one of the last European states to intro- duce voting and representation rights for In the past, the ruling thrones of Eu- women. Up to this point, Swiss women rope were almost exclusively occupied had been denied political office. Swit- by men. Women who ruled in their own zerland is still a long way from gender right were the exception. In many coun- equality in terms of numbers, both in par- tries, female family members were ex- liament and the Federal Council. cluded from succession to the throne by law. However, even in countries which did not recognize a female line of suc- cession, it was not unusual for female regents to be able to reign for a limited period as a substitute for a male ruler. In the subordinate role of mother or wife to the king, too, women were far from powerless and were able to pull strings politically. With the French Revolution of 1789, the absolutist form of government was abol- ished and new political relations estab- lished. These were based on the prin- ciple that the people, not a single ruler, were holders of state power. -

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

Ravalli County 4-H Horse Project Guidelines

4-H PLEDGE I Pledge my HEAD to clearer thinking, My HEART to greater loyalty, My HANDS to larger service, And my HEALTH to better living, RAVALLI COUNTY 4-H For my club, my community, my country and my world. HORSE PROJECT GUIDELINES 2017-2018 The guidelines may be amended by the Ravalli County 4-H Horse Committee each year between October 1st and January 30th. No changes will be made from February 1st through September 30th. If any member or leader wants to request an exception to any rule in the guidelines, they must request a hearing with the Ravalli County 4-H Horse Committee. Updated December 2017 Table of Contents RAVALLI COUNTY 4-H HORSE COMMITTEE CONSTITUTION ............................................................................................................................. 3 ARTICLE I - Name ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 ARTICLE II - Purpose ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 ARTICLE III - Membership ............................................................................................................................................................................... 3 ARTICLE IV - Meetings .................................................................................................................................................................................... -

1914 Girl's Afternoon Dress Pattern Notes

1914 Girl's Afternoon Dress Pattern Notes: I created this pattern as a companion for my women’s 1914 Afternoon Dress pattern. At right is an illustration from the 1914 Home Pattern Company catalogue. This is, essentially, what this pattern looks like if you make it up with an overskirt and cap sleeves. To get this exact look, you’d embroider the overskirt (or use eyelet), add a ruffle around the neckline and put cuffs on the straight sleeves. But the possibilities are as limitless as your imagination! Styles for little girls in 1914 had changed very little from the early Edwardian era—they just “relaxed” a bit. Sleeves and skirt styles varied somewhat over the years, but the basic silhouette remained the same. In the appendix of the print pattern, I give you several examples from clothing and pattern catalogues from 1902-1912 to show you how easy it is to take this basic pattern and modify it slightly for different years. Skirt length during the early 1900s was generally right at or just below the knee. If you make a deep hem on this pattern, that is where the skirt will hit. However, I prefer longer skirts and so made the pattern pieces long enough that the skirt will hit at mid-calf if you make a narrow hem. Of course, I always recommend that you measure the individual child for hem length. Not every child will fit exactly into one “standard” set of pattern measurements, as you’ll read below! Before you begin, please read all of the instructions. -

Augusta Auction Company Historic Fashion & Textile

AUGUSTA AUCTION COMPANY HISTORIC FASHION & TEXTILE AUCTION MAY 9, 2017 STURBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 1 TRAINED CHARMEUSE EVENING GOWN, c. 1912 Cream silk charmeuse w/ vine & blossom pattern, empire bodice w/ silk lace & sequin overlay, B to 38", W 28", L 53"-67", (small holes to lace, minor thread pulls) very good. MCNY 2 DECO LAME EVENING GOWN, LATE 1920s Black silk satin, pewter lame in Deco pattern, B to 36", Low W to 38", L 44"-51", excellent. MCNY 3 TWO EMBELLISHED EVENING GOWNS, 1930s 1 purple silk chiffon, attached lace trimmed cape, rhinestone bands to back & on belt, B to 38", W to 31", L 58", (small stains to F, few holes on tiers) fair; 1 rose taffeta underdress overlaid w/ copper tulle & green silk flounce, CB tulle drape, silk ribbon floral trim, B to 38", W 28", L 60", NY label "Blanche Yovin", (holes to net, long light hem stains) fair- good. MCNY 4 RHINESTONE & VELVET EVENING DRESS, c. 1924 Sapphire velvet studded w/ rhinestones, lame under bodice, B 32", H 36", L 50"-53", (missing stones, lame pulls, pink lining added & stained, shoulder straps pinned to shorten for photo) very good. MCNY 5 MOLYNEUX COUTURE & GUGGENHEIM GOWNS, 1930-1950s Both black silk & labeled: 1 late 30s ribbed crepe, "Molyneux", couture tape "11415", surplice bodice & button back, B to 40", W to 34", H to 38", L 58", yellow & black ikat sash included, (1 missing button) excellent; "Mingolini Guggenheim Roma", strapless multi-layered sheath, B 34", W 23", H 35", CL 46"-50", (CF seam unprofessionally taken in by hand, zipper needs replacing) very good. -

Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form

Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 1 Apply style tape to your dress form to establish the bust level. Tape from the left apex to the side seam on the right side of the dress form. 1 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 2 Place style tape along the front princess line from shoulder line to waistline. 2 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 3A On the back, measure the neck to the waist and divide that by 4. The top fourth is the shoulder blade level. 3 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 3B Style tape the shoulder blade level from center back to the armhole ridge. Be sure that your guidelines lines are parallel to the floor. 4 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 4 Place style tape along the back princess line from shoulder to waist. 5 Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 1 To find the width of your center front block, measure the widest part of the cross chest, from princess line to centerfront and add 4”. Record that measurement. 6 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 2 For your side front block, measure the widest part from apex to side seam and add 4”. 7 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 3 For the length of both blocks, measure from the neckband to the middle of the waist tape and add 4”. 8 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 4 On the back, measure at the widest part of the center back to princess style line and add 4”. -

Registre Des Votes Par Procuration

Registre des votes par procuration pour l’exercice clos le 30 juin 2020 Fonds mondial de gestion de la volatilité Registre des votes par procuration © SEI 2020 seic.com/fr-ca global_2020.txt ******************************* FORM N‐Px REPORT ******************************* Fund Name : GLOBAL MANAGED VOLATILITY FUND _______________________________________________________________________________ AEON REIT Investment Corporation Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status 3292 CINS J10006104 10/17/2019 Voted Meeting Type Country of Trade Special Japan Issue No. Description Proponent Mgmt Rec Vote Cast For/Against Mgmt 1 Elect Nobuaki Seki as Mgmt For For For Executive Director 2 Elect Tetsuya Arisaka Mgmt For For For 3 Elect Akifumi Togawa Mgmt For For For 4 Elect Chiyu Abo Mgmt For For For 5 Elect Yoko Seki Mgmt For For For ________________________________________________________________________________ Aflac Incorporated Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status AFL CUSIP 001055102 05/04/2020 Voted Meeting Type Country of Trade Annual United States Issue No. Description Proponent Mgmt Rec Vote Cast For/Against Mgmt 1 Elect Daniel P. Amos Mgmt For For For 2 Elect W. Paul Bowers Mgmt For For For 3 Elect Toshihiko Mgmt For For For Fukuzawa 4 Elect Thomas J. Kenny Mgmt For For For 5 Elect Georgette D. Mgmt For For For Kiser 6 Elect Karole F. Lloyd Mgmt For For For 7 Elect Nobuchika Mori Mgmt For For For 8 Elect Joseph L. Mgmt For For For Moskowitz 9 Elect Barbara K. Rimer Mgmt For For For 10 Elect Katherine T. Mgmt For For For Rohrer Page 1 global_2020.txt 11 Elect Melvin T. Stith Mgmt For For For 12 Advisory Vote on Mgmt For For For Executive Compensation 13 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For Against Against ________________________________________________________________________________ Ageas SA/NV Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status AGS CINS B0148L138 04/23/2020 Voted Meeting Type Country of Trade Special Belgium Issue No. -

The Shape of Women: Corsets, Crinolines & Bustles

The Shape of Women: Corsets, Crinolines & Bustles – c. 1790-1900 1790-1809 – Neoclassicism In the late 18th century, the latest fashions were influenced by the Rococo and Neo-classical tastes of the French royal courts. Elaborate striped silk gowns gave way to plain white ones made from printed cotton, calico or muslin. The dresses were typically high-waisted (empire line) narrow tubular shifts, unboned and unfitted, but their minimalist style and tight silhouette would have made them extremely unforgiving! Underneath these dresses, the wearer would have worn a cotton shift, under-slip and half-stays (similar to a corset) stiffened with strips of whalebone to support the bust, but it would have been impossible for them to have worn the multiple layers of foundation garments that they had done previously. (Left) Fashion plate showing the neoclassical style of dresses popular in the late 18th century (Right) a similar style ball- gown in the museum’s collections, reputedly worn at the Duchess of Richmond’s ball (1815) There was public outcry about these “naked fashions,” but by modern standards, the quantity of underclothes worn was far from alarming. What was so shocking to the Regency sense of prudery was the novelty of a dress made of such transparent material as to allow a “liberal revelation of the human shape” compared to what had gone before, when the aim had been to conceal the figure. Women adopted split-leg drawers, which had previously been the preserve of men, and subsequently pantalettes (pantaloons), where the lower section of the leg was intended to be seen, which was deemed even more shocking! On a practical note, wearing a short sleeved thin muslin shift dress in the cold British climate would have been far from ideal, which gave way to a growing trend for wearing stoles, capes and pelisses to provide additional warmth. -

FALL / WINTER 2017/2018 2017. Is It Fall and Winter?

THE FASHION GROUP FOUNDATION PRESENTS FALL / WINTER 2017/2018 TREND OVERVIEW BY MARYLOU LUTHER N E W Y O R K • LONDON • MILAN • PARIS DOLCE & GABBANA 2017. Is it Fall and Winter? Now and Next? Or a fluid season of see it/buy it and see it/wait for it? The key word is fluid, as in… Gender Fluid. As more women lead the same business lives as men, the more the clothes for those shared needs become less sex-specific. Raf Simons of Calvin Klein and Anna Sui showed men and women in identical outfits. For the first time, significant numbers of male models shared the runways with female models. Some designers showed menswear separately from women’s wear but sequentially at the same site. Transgender Fluid. Marc Jacobs and Proenza Schouler hired transgender models. Transsexuals also modeled in London, Milan and Paris. On the runways, diversity is the meme of the season. Model selections are more inclusive—not only gender fluid, but also age fluid, race fluid, size fluid, religion fluid. And Location Fluid. Philipp Plein leaves Milan for New York. Rodarte’s Kate and Laura Mulleavy leave New York for Paris. Tommy Hilfiger, Rebecca Minkoff and Rachel Comey leave New York for Los Angeles. Tom Ford returns to New York from London and Los Angeles. Given all this fluidity, you could say: This is Fashion’s Watershed Moment. The moment of Woman as Warrior—armed and ready for the battlefield. Woman in Control of Her Body—to reveal, as in the peekaboobs by Anthony Vaccarello for Yves Saint Laurent. -

Temple University Vendor List

Temple University Vendor List 19Nine LLC Contact: Aaron Loomer 224-217-7073 5868 N Washington Indianapolis, IN 46220 [email protected] www.19nine.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1112269 Standard Effective Products: Otherwear - Shorts Stationary, Greeting Cards & N - Stickers T-Shirts - T-Shirts 3Click Inc Contact: Joseph Domosh 833-325-4253 PO Box 2315 Bala Cynwyd, PA 19004 [email protected] www.3clickpromotions.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1114550 Internal Usage Effective Products: Housewares - Water Bottles Miscellaneous - Koozie Miscellaneous - Cell Phone Accessory Item Miscellaneous - Sunglasses School Supplies - Pen Short sleeve - t-shirt short sleeve Stationary, Greeting Cards & N - Notepad 47 Brand LLC Contact: Kevin Meisinger 781-320-1384 15 Southwest Park Westwood, MA 02090 [email protected] www.twinsenterprise.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1013854 Standard Effective 1013856 Co-branded/Operation Hat Trick Effective 1013855 Vintage Marks Effective Products: Accessories - Gloves Accessories - Scarf Fashion Apparel - Sweater Fashion Apparel - Rugby Shirt Fleece - Sweatshirt Fleece - Sweatpants Headwear - Visor Headwear - Knit Caps 01/21/2020 Page 1 of 79 Headwear - Baseball Cap Mens/Unisex Socks - Socks Otherwear - Shorts Replica Football - Football Jersey Replica Hockey - Hockey Jersey T-Shirts - T-Shirts Womens Apparel - Womens Sweatpants Womens Apparel - Capris Womens Apparel - Womens Sweatshirt Womens Apparel - Dress Womens Apparel - Sweater 4imprint Inc. Contact: Karla Kohlmann 866-624-3694 101 Commerce -

Clothing of Pioneer Women of Dakota Territory, 1861-1889

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Electronic Theses and Dissertations 1978 Clothing of Pioneer Women of Dakota Territory, 1861-1889 Joyce Marie Larson Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Part of the Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, and the Interior Design Commons Recommended Citation Larson, Joyce Marie, "Clothing of Pioneer Women of Dakota Territory, 1861-1889" (1978). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 5565. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/5565 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CWTHIFG OF PIONEER WOMEN OF DAKOTA TERRI'IORY, 1861-1889 BY JOYCE MARIE LARSON A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Haster of Science, Najor in Textiles, Clothing and Interior Design, South Dakota State University 1978 CLO'IHING OF PIONEER WOHEU OF DAKOTA TERRITORY, 1861-1889 This thesis is approved as a creditable and independent investigation by a candidate for the degree, Master of Science, and is acceptable for meeting the thesis requirements for this degree. Acceptance of this thesis does not imply that the conclusions reached by the candidate are necessarily the conclusions of the major department. Merlene Lyman� Thlsis Adviser Date Ardyce Gilbffet, Dean Date College of �ome Economics ACKNOWLEDGEr1ENTS The author wishes to express her warm and sincere appre ciation to the entire Textiles, Clothing and Interior Design staff for their assistance and cooperation during this research. -

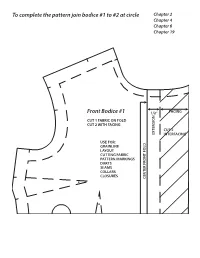

To Complete the Pattern Join Bodice #1 to #2 at Circle Front Bodice #1

To complete the pattern join bodice #1 to #2 at circle Chapter 2 Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Chapter 19 Front Bodice #1 1/2” FACING N CUT 1 FABRIC ON FOLD CUT 2 WITH FACING CUT 2 EXTENSIO INTERFACING USE FOR: GRAINLINE LAYOUT CUTTING FABRIC PATTERN MARKINGS DARTS SEAMS COLLARS CLOSURES CENTER FRONT FOLD To completeTo the pattern join bodice #1 to #2 at circle TO COMPLETE THE PATTERN JOIN BODICE #1 TO #2 AT CIRCLE STITCH TO MATCHPOINTS FOR DART TUCK FRONT BODICE #2 Front Bodice #2 Chapter 2 Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Chapter 19 STITCH TO MATCHPOINTS FOR DART TUCKS To complete the pattern join bodice #3 to #4 at circle Chapter 2 Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Back Bodice #3 CUT 2 FABRIC USE FOR: CK SEAM GRAINLINE LAYOUT CUTTING FABRIC CK FOLD PATTERN MARKINGS DARTS SEAMS COLLARS CENTER BA CUT HERE FOR CENTER BA To completeTo the pattern join bodice #3 to #4 at circle STITCH TO MATCHPOINTS FOR DART TUCKS Back Bodice #4 Chapter 2 Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Chapter 4 Chapter 11 Chapter 14 Chapter 17 MATCHPOINT Front Skirt #5 CUT 1 FABRIC USE FOR: V SHAPED SEAM WAISTBAND WAIST FACING BIAS WAIST FINISH CURVED/ALINE HEM BIAS FALSE HEM CENTER FRONT FOLD Chapter 4 Chapter 11 Chapter 14 Front Yoke #6 CUT 1 FABRIC CUT 1 INTERFACING USE FOR: V SHAPE SEAM WAISTBAND WAIST FACING BIAS WAIST FINISH C. F. FOLD C. F. MATCHPOINT Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 14 Chapter 17 MARK DART POINT HERE Back Skirt #7 CUT 2 FABRIC USE FOR: SEAMS ZIPPERS WAISTBAND WAIST FACING BIAS WAIST FINISH CURVED ALINE HEM BIAS FALSE HEM Chapter 4 CUT ON FOLD Chapter 12 Chapter 17 H TC NO WHEN