Stony Brook University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resiliency Factors Among Transgender People of Color Maureen Grace White University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2013 Resiliency Factors Among Transgender People of Color Maureen Grace White University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Cognitive Psychology Commons, and the Educational Psychology Commons Recommended Citation White, Maureen Grace, "Resiliency Factors Among Transgender People of Color" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 182. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/182 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESILIENCY FACTORS AMONG TRANSGENDER PEOPLE OF COLOR by Maureen G. White A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Psychology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2013 ABSTRACT RESILIENCY FACTORS AMONG TRANSGENDER PEOPLE OF COLOR by Maureen G. White The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Dr. Shannon Chavez-Korell Much of the research on transgender individuals has been geared towards identifying risk factors including suicide, HIV, and poverty. Little to no research has been conducted on resiliency factors within the transgender community. The few research studies that have focused on transgender individuals have made little or no reference to transgender people of color. This study utilized the Consensual Qualitative Research (CQR) approach to examine resiliency factors among eleven transgender people of color. -

Opening the Door Transgender People National Center for Transgender Equality

opening the door the opening The National Center for Transgender Equality is a national social justice people transgender of inclusion the to organization devoted to ending discrimination and violence against transgender people through education and advocacy on national issues of importance to transgender people. www.nctequality.org opening the door NATIO to the inclusion of N transgender people AL GAY AL A GAY NATIO N N D The National Gay and Lesbian AL THE NINE KEYS TO MAKING LESBIAN, GAY, L Task Force Policy Institute ESBIA C BISEXUAL AND TRANSGENDER ORGANIZATIONS is a think tank dedicated to E N FULLY TRANSGENDER-INCLUSIVE research, policy analysis and TER N strategy development to advance T ASK FORCE F greater understanding and OR equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual T and transgender people. RA N by Lisa Mottet S G POLICY E and Justin Tanis N DER www.theTaskForce.org IN E QUALITY STITUTE NATIONAL GAY AND LESBIAN TASK FORCE POLICY INSTITUTE NATIONAL CENTER FOR TRANSGENDER EQUALITY this page intentionally left blank opening the door to the inclusion of transgender people THE NINE KEYS TO MAKING LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL AND TRANSGENDER ORGANIZATIONS FULLY TRANSGENDER-INCLUSIVE by Lisa Mottet and Justin Tanis NATIONAL GAY AND LESBIAN TASK FORCE POLICY INSTITUTE National CENTER FOR TRANSGENDER EQUALITY OPENING THE DOOR The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute is a think tank dedicated to research, policy analysis and strategy development to advance greater understanding and equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender -

STONEWALL Riotsstro

Everyday hero. Ordinary world. Compelling villain. Call to adventure. Crossing the threshold. STONEWALL RIOTS STONEWALL strongerstories.org Allies, mentors and gifts. Three challenges. Better world. Everyday hero. Ordinary world. Compelling villain. Call to adventure. Crossing the threshold. The Stonewall Inn The 1960s were difficult Thanks to activists Raid: 1:20 a.m. Procedure was to line up community – an important for LGBTQ+ Americans. alcohol regulations were 28/06/1969, 6 policemen, the patrons, check their Greenwich Village Solicitation of same-sex overturned. But engaging 1 detective and 1 ID, and have police institution. The relations was illegal in in homosexual behaviour inspector arrived yelling officers take customers Stonewall Inn was large, New York, and there was in public (holding "Police! We're taking the to the toilet to verify RIOTS STONEWALL cheap to enter, welcomed a criminal statute that hands, kissing, dancing) place!” Stonewall their sex. That night Drag Queens (others allowed police to arrest was still illegal, so employees do not recall customers refused to go usually didn't) and it people wearing less than police harassment being tipped off that a with the officers. Stormé was a nightly home for three gender-appropriate continued. Rampant raid was to occur, as was DeLarverie fought back many runaway homeless clothes. The State institutionalised the custom. The music was against the police LGBTQ+ youths. It was Liquor Authority homophobia and turned off and the lights officer who attempted to one of the few - if not penalised and shut down transphobia – the turned on, and the police arrest her. She shouted the only – LGBTQ+ bar establishments that Stonewall Riots specific barricaded the doors. -

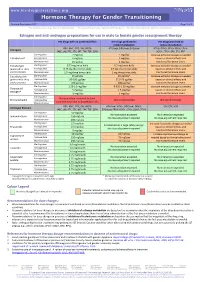

Hormone Therapy for Gender Transitioning Revised September 2017 Page 1 of 2 for Personal Use Only

www.hiv-druginteractions.org Hormone Therapy for Gender Transitioning Revised September 2017 Page 1 of 2 For personal use only. Not for distribution. For personal use only. Not for distribution. For personal use only. Not for distribution. Estrogen and anti-androgen preparations for use in male to female gender reassignment therapy HIV drugs with no predicted effect HIV drugs predicted to HIV drugs predicted to inhibit metabolism induce metabolism RPV, MVC, DTG, RAL, NRTIs ATV/cobi, DRV/cobi, EVG/cobi ATV/r, DRV/r, FPV/r, IDV/r, LPV/r, Estrogens (ABC, ddI, FTC, 3TC, d4T, TAF, TDF, ZDV) SQV/r, TPV/r, EFV, ETV, NVP Starting dose 2 mg/day 1 mg/day Increase estradiol dosage as needed Estradiol oral Average dose 4 mg/day 2 mg/day based on clinical effects and Maximum dose 8 mg/day 4 mg/day monitored hormone levels. Estradiol gel Starting dose 0.75 mg twice daily 0.5 mg twice daily Increase estradiol dosage as needed (preferred for >40 y Average dose 0.75 mg three times daily 0.5 mg three times daily based on clinical effects and and/or smokers) Maximum dose 1.5 mg three times daily 1 mg three times daily monitored hormone levels. Estradiol patch Starting dose 25 µg/day 25 µg/day* Increase estradiol dosage as needed (preferred for >40 y Average dose 50-100 µg/day 37.5-75 µg/day based on clinical effects and and/or smokers) Maximum dose 150 µg/day 100 µg/day monitored hormone levels. Starting dose 1.25-2.5 mg/day 0.625-1.25 mg/day Increase estradiol dosage as needed Conjugated Average dose 5 mg/day 2.5 mg/day based on clinical effects and estrogen† Maximum dose 10 mg/day 5 mg/day monitored hormone levels. -

Safe Zone Manual – Edited 9.15.2015 1

Fall 2015 UCM SAFE ZONE GUIDE FOR ALLIES UCM – Safe Zone Manual – Edited 9.15.2015 1 Contents Safe Zone Program Introduction .............................................................................................................. 4 Terms, Definitions, and Labels ................................................................................................................. 6 Symbols and Flags................................................................................................................................... 19 Gender Identity ......................................................................................................................................... 24 What is Homophobia? ............................................................................................................................. 25 Biphobia – Myths and Realities of Bisexuality ..................................................................................... 26 Transphobia- Myths & Realities of Transgender ................................................................................. 28 Homophobia/biphobia/transphobia in Clinical Terms: The Riddle Scale ......................................... 30 How Homophobia/biphobia/transphobia Hurts Us All......................................................................... 32 National Statistics and Research Findings ........................................................................................... 33 Missouri State “Snapshot” ...................................................................................................................... -

Trans People, Transitioning, Mental Health, Life and Job Satisfaction

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12695 Trans People, Transitioning, Mental Health, Life and Job Satisfaction Nick Drydakis OCTOBER 2019 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12695 Trans People, Transitioning, Mental Health, Life and Job Satisfaction Nick Drydakis Anglia Ruskin University, University of Cambridge and IZA OCTOBER 2019 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. ISSN: 2365-9793 IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 12695 OCTOBER 2019 ABSTRACT Trans People, Transitioning, Mental Health, Life and Job Satisfaction For trans people (i.e. people whose gender is not the same as the sex they were assigned at birth) evidence suggests that transitioning (i.e. -

The Spark of Stonewall

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by James Madison University James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Proceedings of the Sixth Annual MadRush MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference Conference: Best Papers, Spring 2015 A Movement on the Verge: The pS ark of Stonewall Tiffany Renee Nelson James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush Part of the Social History Commons Tiffany Renee Nelson, "A Movement on the Verge: The pS ark of Stonewall" (April 10, 2015). MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference. Paper 1. http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush/2015/SocialMovements/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conference Proceedings at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Movement on the Verge: The Spark of Stonewall The night of Saturday, June 28, 1969, the streets of Central Greenwich Village were crowded with angered gay men, lesbians, “flame queens”, and Trans*genders. 1 That was the second day of disorder of what would later be called the Stonewall Riots. Centering around Christopher Street’s bar for homosexuals, the Stonewall Inn, the riots began the night before on June 27 and lasted until July 2. These five days of rioting were the result of decades of disdain against the police force and the general population that had oppressed the gay inhabitants of New York City. -

The Frames and Depictions of Transgender Athletes in Sports Illustrated

THESIS DECOLONIZING TRANSNESS IN SPORT MEDIA: THE FRAMES AND DEPICTIONS OF TRANSGENDER ATHLETES IN SPORTS ILLUSTRATED Submitted By Tammy Rae Matthews Department of Journalism and Media Communication In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Fall 2016 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Catherine Knight Steele Co-Advisor: Kris Kodrich Joseph Champ Caridad Souza Copyright by Tammy Rae Matthews 2016 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT DECOLONIZING TRANSNESS IN SPORT MEDIA: THE FRAMES AND DEPICTIONS OF TRANSGENDER ATHLETES IN SPORTS ILLUSTRATED This discourse analysis examines depictions of trans athletes in Sports Illustrated and sport culture through the lens of queer theory and the interpretive-packages model proposed by Gamson and Modigliani (1989). Four interpretive packages emerged from the print content: (1) Marginalization, (2) Labeling, (3) Fighting and Fairness and (4) Pride and Affirmation. The results illustrate that discourse has generally become more sensitive to trans issues. The author presents these results with cautious optimism. Blindingly affirming and romancing the transgender can be equally as superficial as marginalization, and representations of trans athletes secured by one person are problematic. Researchers and sport organizations should dismantle antiquated, coercive sex segregation in traditional sport and decolonize how it contributes to gender-based oppression. The author recommends that media outlets focus on presenting fair, accurate and -

Guidelines for Supporting Gender Transitioning Employees City and County of Denver, Office of Human Resources Revised July 22, 2020

Guidelines for Supporting Gender Transitioning Employees City and County of Denver, Office of Human Resources Revised July 22, 2020 Contents Contents ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Purpose and Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 2 Terminology and Definitions ......................................................................................................................... 2 Applicable City and County of Denver Policies ............................................................................................. 3 Guidelines for Human Resources & Management ....................................................................................... 3 Guidelines for Co-Workers ............................................................................................................................ 4 Recommended Behaviors for LGBT Allies ................................................................................................ 4 Appearance, Names and Pronouns .......................................................................................................... 4 Benefits and Leave ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Sex-Segregated Facilities .............................................................................................................................. -

Gm Celebrates Pride Month in June!

together we will build the world’s best propulsion systems GM St. Catharines Employee Newsletter May 28, 2018 GM CELEBRATES PRIDE MONTH IN JUNE! General Motors values and respects individual differences – we appreciate what each individual brings to the team including background, education, gender, race, ethnicity, working and thinking styles, sexual orientation, gender identity, veteran status, religious background, age, generation, disability, cultural expertise and technical skills. Empowering these unique perspectives keeps GM on the cutting edge of technological innovation in the fast-paced automotive industry. To win in this dynamic, competitive environment, GM needs a talented, diverse workforce that shares a passion for solving the world’s mobility challenges, and employees who want to make the world a better place. At GM, we’re creating a culture, an energy and an attitude that says anything is possible, especially when we ensure that every employee has a chance to contribute to his or her full potential. That’s why, in support of pride month in Canada, all GM Canada facilities will fly the rainbow pride flag and the transgender flag in support of diversity for the entire month. This will also be our first year flying the transgender flag alongside the pride flag. Pride month is about celebrating our vibrant and increasingly diverse work force. Our employee resource groups (ERGs), like GM PLUS play a key role in fostering an inclusive place to work. These groups provide a forum for employees to share common concerns and experiences, gain professional development support and engage in local communities. GM PLUS is an active research, marketing, educational and advocacy resource for GM on topics relevant to the LGBT and allied community. -

"Love Is Gender Blind": the Lived Experiences of Transgender Couples Who Navigate One Partner's Gender Transition Barry Lynn Motter

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 8-2017 "Love is Gender Blind": The Lived Experiences of Transgender Couples Who Navigate One Partner's Gender Transition Barry Lynn Motter Follow this and additional works at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Motter, Barry Lynn, ""Love is Gender Blind": The Lived Experiences of Transgender Couples Who Navigate One Partner's Gender Transition" (2017). Dissertations. 428. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations/428 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2017 BARRY LYNN MOTTER ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School “LOVE IS GENDER BLIND”: THE LIVED EXPERIENCES OF TRANSGENDER COUPLES WHO NAVIGATE ONE PARTNER’S GENDER TRANSITION A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Barry Lynn Motter College of Education and Behavioral Sciences Department of Applied Psychology and Counselor Education Program of Counseling Psychology August 2017 This Dissertation by: Barry Lynn Motter Entitled: “Love is Gender Blind:” The Lived Experiences of Transgender Couples Who Navigate One Partner’s Gender Transition has been approved as -

Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Substance Use Disorders

Beck Whipple, BS Staff Development Coordinator, Maryhurst, Louisville, KY [email protected] Ed Johnson, M.Ed, MAC, LPC, CCS Associate Director, Training and Technical Assistance Southeast Addiction Technology Transfer Center (Southeast ATTC) [email protected] www.attcnetwork.org/southeast Participants will gain understanding of: The difference between Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation. Increase their understanding of the impact of trauma on Individuals who are LGBTQ and it’s relationship to unsuccessful treatment outcomes The concept of LGBTQ (Minority) Stress Be able to identify ways of creating supportive, affirming and inclusive treatment environments. This training does not aim to be the definitive resource, nor does it intend to speak on behalf of all LGBTQ people. We encourage training participants to research and engage local LGBTQ organizations, providers and constituents. Building partnerships with local LGBTQ entities can help increase your understanding of the LGBTQ community needs and increase referral options for your clients. Stigma – A mark of disgrace or infamy associated with a particular circumstance, quality or person. A painful feeling of humiliation or distress caused by the consciousness of wrong or foolish behavior. It is differentiated from guilt in that guilt involves a behavior, shame involves the intrinsic sense of one’s self. Guilt- I behaved badly; Shame – I am bad. Stigmatizing Words Alternative Terminology Addict, Abuser, Junkie, Person in active addiction, person with a substance use User