INSTITUTE of TRANSPORT and LOGISTICS STUDIES WORKING

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WORLD AVIATION Yearbook 2013 EUROPE

WORLD AVIATION Yearbook 2013 EUROPE 1 PROFILES W ESTERN EUROPE TOP 10 AIRLINES SOURCE: CAPA - CENTRE FOR AVIATION AND INNOVATA | WEEK startinG 31-MAR-2013 R ANKING CARRIER NAME SEATS Lufthansa 1 Lufthansa 1,739,886 Ryanair 2 Ryanair 1,604,799 Air France 3 Air France 1,329,819 easyJet Britis 4 easyJet 1,200,528 Airways 5 British Airways 1,025,222 SAS 6 SAS 703,817 airberlin KLM Royal 7 airberlin 609,008 Dutch Airlines 8 KLM Royal Dutch Airlines 571,584 Iberia 9 Iberia 534,125 Other Western 10 Norwegian Air Shuttle 494,828 W ESTERN EUROPE TOP 10 AIRPORTS SOURCE: CAPA - CENTRE FOR AVIATION AND INNOVATA | WEEK startinG 31-MAR-2013 Europe R ANKING CARRIER NAME SEATS 1 London Heathrow Airport 1,774,606 2 Paris Charles De Gaulle Airport 1,421,231 Outlook 3 Frankfurt Airport 1,394,143 4 Amsterdam Airport Schiphol 1,052,624 5 Madrid Barajas Airport 1,016,791 HE EUROPEAN AIRLINE MARKET 6 Munich Airport 1,007,000 HAS A NUMBER OF DIVIDING LINES. 7 Rome Fiumicino Airport 812,178 There is little growth on routes within the 8 Barcelona El Prat Airport 768,004 continent, but steady growth on long-haul. MostT of the growth within Europe goes to low-cost 9 Paris Orly Field 683,097 carriers, while the major legacy groups restructure 10 London Gatwick Airport 622,909 their short/medium-haul activities. The big Western countries see little or negative traffic growth, while the East enjoys a growth spurt ... ... On the other hand, the big Western airline groups continue to lead consolidation, while many in the East struggle to survive. -

Aviation Industry Agreed in 2008 to the World’S First Set of Sector-Specific Climate Change Targets

CONTENTS Introduction 2 Executive summary 3 Key facts and figures from the world of air transport A global industry, driving sustainable development 11 Aviation’s global economic, social and environmental profile in 2016 Regional and group analysis 39 Africa 40 Asia-Pacific 42 Europe 44 Latin America and the Caribbean 46 Middle East 48 North America 50 APEC economies 52 European Union 53 Small island states 54 Developing countries 55 OECD countries 56 Least-developed countries 57 Landlocked developing countries 58 National analysis 59 A country-by-country look at aviation’s benefits A growth industry 75 An assessment of the next 20 years of aviation References 80 Methodology 84 1 AVIATION BENEFITS BEYOND BORDERS INTRODUCTION Open skies, open minds The preamble to the Chicago Convention – in many ways aviation’s constitution – says that the “future development of international civil aviation can greatly help to create and preserve friendship and understanding among the nations and peoples of the world”. Drafted in December 1944, the Convention also illustrates a sentiment that underpins the construction of the post-World War Two multilateral economic system: that by trading with one another, we are far less likely to fight one another. This pursuit of peace helped create the United Nations and other elements of our multilateral system and, although these institutions are never perfect, they have for the most part achieved that most basic aim: peace. Air travel, too, played its own important role. If trading with others helps to break down barriers, then meeting and learning from each other surely goes even further. -

Singapore Airshow Comes of Age with $32Bn in Orders

ISSN 1718-7966 FEBRUARY 17, 2014 / VOL. 426 WEEKLY AVIATION HEADLINES Read by thousands of aviation professionals and technical decision-makers every week www.avitrader.com WORLD NEWS Airbus to set up own bank Airbus Group bought shares in a Munich-based bank, which will be renamed Airbus Group Bank and The Airbus which will be developed to pro- A350 (left) vide finance solutions to support was on the Group’s businesses. The deal display last is expected to be closed within the week at the Singapore coming weeks. Airshow See page 12 for more information Rolls-Royce net profit fall Airbus Rolls-Royce, the British engine-mak- er, warned that expected revenue growth to be flat in 2014 for the Singapore Airshow comes of age with $32bn in orders first time in a decade, after posting New Southeast Asian low-cost carriers fuel burgeoning demand a 41-per-cent fall in net profits in Singapore confirmed its place as 2013. Despite strong performances host of one of the four largest Singapore Airshow 2014: Key orders by its commercial aviation division, global airshows in the world af- Customer Provider Order Value¹ the ongoing cuts in the global mili- ter Paris, Farnborough and Du- Turkish Airlines IAE V2500 engines for 25 A321 $560m tary sector are ‘rolling through and bai after it closed its doors on hitting us’, according to chief ex- Myanma Airways GECAS Lease of 10 737 family jets $1bn the fourth edition of the event ecutive John Rishton. VietJetAir Airbus up to 100 A320 family jets $9bn² last week, with deals worth a VietJetAir CFM International CFM56-5Bs for 21 A320s $800m Norwegian gets Irish base record $32bn - $1bn more than the previous record set at the Norwegian secured final approval Amedeo Airbus Firm order: 20 A380s $8.3bn 2012 edition. -

Tajikistan): 2014 Country Commercial Guide for U.S

Doing Business in (Tajikistan): 2014 Country Commercial Guide for U.S. Companies INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT, U.S. & FOREIGN COMMERCIAL SERVICE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE, 2010. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED OUTSIDE OF THE UNITED STATES. Chapter 1: Doing Business In … Chapter 2: Political and Economic Environment Chapter 3: Selling U.S. Products and Services Chapter 4: Leading Sectors for U.S. Export and Investment Chapter 5: Trade Regulations, Customs and Standards Chapter 6: Investment Climate Chapter 7: Trade and Project Financing Chapter 8: Business Travel Chapter 9: Contacts, Market Research and Trade Events Chapter 10: Guide to Our Services Return to table of contents Chapter 1: Doing Business In Tajikistan Market Overview Market Challenges Market Opportunities Market Entry Strategy Market Overview Return to top Tajikistan’s economy provides a number of opportunities for exporters and investors. With a population of 8.1 million and number of potentially sizeable infrastructure, mining, and tourism projects, Tajikistan has the potential to become a notable market for U.S. exporters. th Tajikistan is the world’s 139 economy with expected per-capita GDP of $$1,050 in 2013. Approximately half of Tajikistan’s two million working-age males labor at least part of the year in Russia and other CIS countries, often for less than the local minimum wage and under difficult working conditions. Tajikistan’s economy is still facing major economic issues left from the 1992-1997 Civil War, despite GDP growth of 7.4% in 2013. Tajikistan may face more economic problems if sanctions imposed against Russia cause its economy to contract. Experts forecast 6.2% real GDP growth and 5.4% inflation in 2014. -

World Air Cargo Forecast 2018–2037 Foreword

WORLD AIR CARGO FORECAST 2018–2037 FOREWORD The Boeing Company issues the biennial World Air The next update to the WACF will appear in fourth Cargo Forecast (WACF) to provide a comprehensive, quarter 2020. The authors welcome any questions up-to-date overview of the air cargo industry. The fore- or comments readers may have. All queries and cast summarizes the world’s major air trade markets, suggestions should be directed to the following: identifies major trends, and presents forecasts for the future performance and development of markets, as BOEING WORLD AIR well as for the world freighter airplane fleet. CARGO FORECAST TEAM This document would not be possible without the Boeing Commercial Airplanes efforts of several contributors. The Boeing World Air P.O. Box 3707, MC 21-33 Cargo Forecast 2018–2037 production team included Seattle, WA 98124-2207 USA Boeing Creative Services, Digital Strategy Team, and our colleagues in the Market Analysis Group. Web We give special thanks to Ryo Abe for his diligent www.boeing.com/commercial/market/cargo-forecast efforts on the Airline Cargo Traffic Database (ACTD), which includes more than 800 airlines, as well as his Tom Crabtree research and authoring of the Intra-Europe and South [email protected] Asia chapters. Thank you also to Wendy Moore, Tom Hoang who researched and modeled the air freight yield [email protected] curves in the Air Cargo Industry Overview; Katrina Krebs, for development of the North America chapter; Russell Tom Adin Herzog, who authored the Latin America and [email protected] Europe chapter, analyzed the historical airline cargo revenues, and assisted in the development of the Air Gregg Gildemann Cargo Industry Overview; Ben Su, for analysis and [email protected] authoring of the Latin America and North America chapter; and Jayden Lee, who developed the insights and analysis behind the Intra–East Asia and Oceania chapter and the Executive Summary. -

CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION CHG 2 Air Traffic Organization Policy Effective Date: November 8, 2018

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2H CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION CHG 2 Air Traffic Organization Policy Effective Date: November 8, 2018 SUBJ: Contractions 1. Purpose of This Change. This change transmits revised pages to Federal Aviation Administration Order JO 7340.2H, Contractions. 2. Audience. This change applies to all Air Traffic Organization (ATO) personnel and anyone using ATO directives. 3. Where Can I Find This Change? This change is available on the FAA website at http://faa.gov/air_traffic/publications and https://employees.faa.gov/tools_resources/orders_notices. 4. Distribution. This change is available online and will be distributed electronically to all offices that subscribe to receive email notification/access to it through the FAA website at http://faa.gov/air_traffic/publications. 5. Disposition of Transmittal. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. Page Control Chart. See the page control chart attachment. Original Signed By: Sharon Kurywchak Sharon Kurywchak Acting Director, Air Traffic Procedures Mission Support Services Air Traffic Organization Date: October 19, 2018 Distribution: Electronic Initiated By: AJV-0 Vice President, Mission Support Services 11/8/18 JO 7340.2H CHG 2 PAGE CONTROL CHART Change 2 REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED CAM 1−1 through CAM 1−38............ 7/19/18 CAM 1−1 through CAM 1−18........... 11/8/18 3−1−1 through 3−4−1................... 7/19/18 3−1−1 through 3−4−1.................. 11/8/18 Page Control Chart i 11/8/18 JO 7340.2H CHG 2 CHANGES, ADDITIONS, AND MODIFICATIONS Chapter 3. ICAO AIRCRAFT COMPANY/TELEPHONY/THREE-LETTER DESIGNATOR AND U.S. -

2.2 Tajikistan Aviation Tajikistan Aviation

2.2 Tajikistan Aviation Tajikistan Aviation Key airport information may also be found at: World Aero Data information on Tajikistan Commercial Aviation Commercial aviation in Tajikistan is regulated by the Central Directorate of Civil Aviation under the Ministry of Transport. Airports operate as separate entities under this authority, with the exception of Khorog, which comes under Dushanbe International Airport because of its need for subsidies. Tajikistan has four international airports (Dushanbe, Khujand, Kulyab and Kurgantyube) with the national airline Tajik Air (government) 12 sites and Somon Air (private) 22 sites, providing service to 9 countries (China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kirgizstan, Iran UAE, India and Germany) and around 20 international airlines. A further Tajikistan-based airline company is East Air. The largest number of flights is from all four international airports to 15 to 20 cities in Russia by around 8 Russian airlines and the two Tajikistan carriers. Scheduled domestic flights are limited to Dushanbe – Khujand (Somon Air 737) and Dushanbe – Khorog (Tajik Air / 17 passenger Dornier). Between Dushanbe and Kabul there are two flights weekly on the Afghan carrier KamAir. Tajik Air, Somon Air, KamAir and a number of the Russian airlines flying to Tajikistan are rated as Category C and not recommended for use by UN staff (Please check with UNDSS about use of airlines in specific circumstances). Dushanbe – Kabul travel is through Dubai (FlyDubai) or Istanbul (Turkish Airlines). There are several other airports in the country including Aini improved with financing from India and Murghab in the Pamirs. They have no regular flights and as road improvements now keep highways open all winter they are infrequently used. -

1 CPWG/25 Summary of Discussions 22-24 May 2018 Summary Of

CPWG/25 Summary of Discussions 22-24 May 2018 Summary of Discussions of the Twenty-Fifth Meeting of the Cross Polar Trans East Air Traffic Management Providers Working Group (CPWG/25) 22-24 May 2018 – Paris, France 1. Background 1.1 The Twenty-Fifth Meeting of the Cross Polar Trans East Air Traffic Management (ATM) Providers Working Group (CPWG/25) was hosted by the International Civil Aviation Organization’s (ICAO) Europe and North Atlantic Office in Paris, France, 12-14 May 2018. The schedule included meetings of the Air Navigation Service Providers (ANSPs) and the CPWG/25 plenary meeting. 1.2 The CPWG was established to provide a forum for ANSPs and airspace users to meet and explore solutions for improving air traffic services (ATS) to aircraft which operate between North America and Asia via Cross Polar (CP) and Russian Trans East (RTE) routes. 1.3 Ms. Leah Moebius, FAA Air Traffic Organization and Mr. Blair Cowles, Regional Director, International Air Transport Association (IATA) co-facilitated the meeting. Attendees included representatives of the ANSPs from Canada, China, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Japan, Norway, the Russian Federation and the United States; ICAO; IATA, international airlines and operators; and industry. The complete list of participants is provided in Attachment A. 2. Opening of the Meeting 2.1 The meeting was opened at 1300 local time. Ms. Moebius welcomed everyone to the 25th CPWG meeting and explained the agenda and the plan for the day and the meeting participants introduced themselves. 3. Agenda Item 1: -

Final of Doing Business in Tajikistan 2015

Doing business in Tajikistan 2015 Commercial guide for investors 2 3 Content Foreword 4 Country profile 6 Economic situation 10 Legal regulation of foreign investments 12 Different investment forms 17 Banking system 25 Regulation and remuneration of labor 29 Fiscal system 34 Import system in Tajikistan 43 Certification and Intellectual Property Rights 46 Cargo transportation 48 Advertising 53 Useful links 55 With the aim of developing the Tajikistan economy through attracting investments in Tajikistan, we have developed this Guide, covering information about the country, its economic state of affairs and other important aspects that might be of interest to foreign investors, and are delighted to present it to you. Gurgen Hakobyan Managing partner Grant Thornton Tajikistan 4 Foreword Grant Thornton Tajikistan is the leading audit and advisory services firm in the market, sharing the Grant Thornton philosophy worldwide. Grant Thornton is one of the world’s leading organisations of independent assurance, tax and advisory firms. These firms help dynamic organisations unlock their potential for growth by providing meaningful, forward looking advice. Proactive teams, led by approachable partners in these firms, use insights, experience and instinct to understand complex issues for privately owned, publicly listed and public sector clients and help them to find solutions. More than 40,000 Grant Thornton people, across over 130 countries, are focused on making a difference to clients, colleagues and the communities in which we live and work. If you require any further information, please do not hesitate to contact your nearest Grant Thornton member firm. This guide has been prepared for the assistance of those interested in doing business in Tajikistan. -

Twenty-Seventh Meeting of the Cross Polar Trans East Air Traffic Management Providers’ Work Group (CPWG/27) (Singapore, 22 – 24 October 2019)

CPWG/27 WP/10 22/10/2019 Twenty-Seventh Meeting of the Cross Polar Trans East Air Traffic Management Providers’ Work Group (CPWG/27) (Singapore, 22 – 24 October 2019) Agenda Item 4: Summary of Pertinent Issues from the ANSPs Meeting and other relevant meetings Summary of Discussions Route Development Group – East (Presented by the United States) Summary This working paper presents information on the thirty-first meeting of the Route Development Group – Eastern Part of the ICAO EUR Region (RDGE/31) was held in the ICAO EUR/NAT Office in Paris, France, from 9 to 13 September 2019 1. Introduction 1.1. The Route Development Group (RDGE) works on matters related to ATS route planning and implementation, as well as airspace improvement projects in the Eastern part of the ICAO European Region. 1.2. The RDGE-E meets bi-annually and consists of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bulgaria, Estonia, Finland, Georgia, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Poland, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Russian Federation, Sweden, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, EUROCONTROL, IAC, IBAC and IATA. For specific coordination matters, any other State within the ICAO EUR Region may also be invited to participate at the RDGE. Other relevant stakeholders may also be invited to participate as observers. 1.3 With regard to specific regional coordination matters the following adjacent States will also be invited: Afghanistan, Canada, China, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Iran, Iraq, Japan, Mongolia, Pakistan, Syrian Arab Republic and the United States. Note: The Cross Polar Working Group (CPWG) could also be invited to participate on specific issues related to ATS route planning and implementation in the Far East Area of the ICAO EUR Region. -

Group ROW by State of Administration

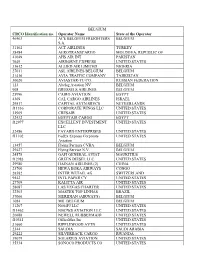

BELGIUM CRCO Identification no. Operator Name State of the Operator 46463 ACE BELGIUM FREIGHTERS BELGIUM S.A. 31102 ACT AIRLINES TURKEY 38484 AEROTRANSCARGO MOLDOVA, REPUBLIC OF 41049 AHS AIR INT PAKISTAN 7649 AIRBORNE EXPRESS UNITED STATES 33612 ALLIED AIR LIMITED NIGERIA 27011 ASL AIRLINES BELGIUM BELGIUM 31416 AVIA TRAFFIC COMPANY TAJIKISTAN 30020 AVIASTAR-TU CO. RUSSIAN FEDERATION 123 Abelag Aviation NV BELGIUM 908 BRUSSELS AIRLINES BELGIUM 25996 CAIRO AVIATION EGYPT 4369 CAL CARGO AIRLINES ISRAEL 29517 CAPITAL AVTN SRVCS NETHERLANDS f11336 CORPORATE WINGS LLC UNITED STATES 32909 CRESAIR UNITED STATES 32432 EGYPTAIR CARGO EGYPT f12977 EXCELLENT INVESTMENT UNITED STATES LLC 32486 FAYARD ENTERPRISES UNITED STATES f11102 FedEx Express Corporate UNITED STATES Aviation 13457 Flying Partners CVBA BELGIUM 29427 Flying Service N.V. BELGIUM 24578 GAFI GENERAL AVIAT MAURITIUS f12983 GREEN DIESEL LLC UNITED STATES 29980 HAINAN AIRLINES (2) CHINA 23700 HEWA BORA AIRWAYS CONGO 28582 INTER WETAIL AG SWITZERLAND 9542 INTL PAPER CY UNITED STATES 27709 KALITTA AIR UNITED STATES 28087 LAS VEGAS CHARTER UNITED STATES 32303 MASTER TOP LINHAS BRAZIL 37066 MERIDIAN (AIRWAYS) BELGIUM 1084 MIL BELGIUM BELGIUM 31207 N604FJ LLC UNITED STATES f11462 N907WS AVIATION LLC UNITED STATES 26688 NEWELL RUBBERMAID UNITED STATES f10341 OfficeMax Inc UNITED STATES 31660 RIPPLEWOOD AVTN UNITED STATES 2344 SAUDIA SAUDI ARABIA 29222 SILVERBACK CARGO RWANDA 39079 SOLARIUS AVIATION UNITED STATES 35334 SONOCO PRODUCTS CO UNITED STATES BELGIUM 26784 SOUTHERN AIR UNITED STATES 38995 STANLEY BLACK&DECKER UNITED STATES 27769 Sea Air BELGIUM 34920 TRIDENT AVIATION SVC UNITED STATES 30011 TUI AIRLINES - JAF BELGIUM 27911 ULTIMATE ACFT SERVIC UNITED STATES 13603 VF CORP UNITED STATES 36269 VF INTERNATIONAL SWITZERLAND 37064 VIPER CLASSICS LTD UNITED KINGDOM f11467 WILSON & ASSOCIATES OF UNITED STATES DELAWARE LLC 37549 YILTAS GROUP TURKEY BULGARIA CRCO Identification no. -

International Civil Aviation Organization WORKING PAPER

APIRG/EO-IP/06 International Civil Aviation Organization Appendix B AN-Conf/12-WP/24 WORKING PAPER TWELFTH AIR NAVIGATION CONFERENCE Agenda Item 6: Future direction 6.1: Implementation plans and methodologies REGIONAL PERFORMANCE FRAMEWORK – ALIGNMENT OF AREAS OF APPLICABILITY OF AIR NAVIGATION PLANS (ANPs) AND REGIONAL SUPPLEMENTARY PROCEDURES (SUPPs) (Presented by the Secretariat) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY At the global level, the performance framework is composed of the Global Air Navigation Plan (GANP, Doc 9750) and the associated procedures as contained in the Procedures for Air Navigation – Air Traffic Management and the Procedures for Air Navigation Services — Aircraft Operations (PANS-OPS, Doc 8168). Under the umbrella of the global performance framework, the regional performance frameworks are facilitated through formulation of regional air navigation plans (ANPs) and the associated regional supplementary procedures (SUPPs). The regional performance frameworks are managed by the planning and implementation regional groups (PIRGs) established by the Council of ICAO. Currently, the areas of applicability of the SUPPs do not coincide with those of the ANPs. Based on a review undertaken by ICAO, this working paper presents a proposal to align these areas of applicability. Without changing the accreditation of ICAO regional offices to States, the proposal will integrate within each of the PIRGs the responsibilities for development and upkeep of ANPs and SUPPs for their respective air navigation regions. This proposed alignment of the areas of applicability of ANPs and SUPPS is expected to simplify the procedures for regional performance framework management for PIRGs and will also support more efficient planning and implementation of the aviation system block upgrades (ASBUs).