Transcript of Interview with [Insert the Name of Interviewee]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

142-2019 Yukhnovskyi.Indd

Original Paper Journal of Forest Science, 66, 2020 (6): 252–263 https://doi.org/10.17221/142/2019-JFS Green space trends in small towns of Kyiv region according to EOS Land Viewer – a case study Vasyl Yukhnovskyi1*, Olha Zibtseva2 1Department of Forests Restoration and Meliorations, Forest Institute, National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine, Kyiv 2Department of Landscape Architecture and Phytodesign, Forest Institute, National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine, Kyiv *Corresponding author: [email protected] Citation: Yukhnovskyi V., Zibtseva O. (2020): Green space trends in small towns of Kyiv region according to EOS Land Viewer – a case study. J. For. Sci., 66: 252–263. Abstract: The state of ecological balance of cities is determined by the analysis of the qualitative composition of green space. The lack of green space inventory in small towns in the Kyiv region has prompted the use of express analysis provided by the EOS Land Viewer platform, which allows obtaining an instantaneous distribution of the urban and suburban territories by a number of vegetative indices and in recent years – by scene classification. The purpose of the study is to determine the current state and dynamics of the ratio of vegetation and built-up cover of the territories of small towns in Kyiv region with establishing the rating of towns by eco-balance of territories. The distribution of the territory of small towns by the most common vegetation index NDVI, as well as by S AVI, which is more suitable for areas with vegetation coverage of less than 30%, has been monitored. -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

State Building in Revolutionary Ukraine

STATE BUILDING IN REVOLUTIONARY UKRAINE Unauthenticated Download Date | 3/31/17 3:49 PM This page intentionally left blank Unauthenticated Download Date | 3/31/17 3:49 PM STEPHEN VELYCHENKO STATE BUILDING IN REVOLUTIONARY UKRAINE A Comparative Study of Governments and Bureaucrats, 1917–1922 UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London Unauthenticated Download Date | 3/31/17 3:49 PM © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2011 Toronto Buffalo London www.utppublishing.com Printed in Canada ISBN 978-1-4426-4132-7 Printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper with vegetable- based inks. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Velychenko, Stephen State building in revolutionary Ukraine: a comparative study of governments and bureaucrats, 1917–1922/Stephen Velychenko. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4426-4132-7 1. Ukraine – Politics and government – 1917–1945. 2. Public adminstration – Ukraine – History – 20th century. 3. Nation-building – Ukraine – History – 20th century 4. Comparative government. I. Title DK508.832.V442011 320.9477'09041 C2010-907040-2 The research for this book was made possible by University of Toronto Humanities and Social Sciences Research Grants, by the Katedra Foundation, and the John Yaremko Teaching Fellowship. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Aid to Scholarly Publications Programme, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the fi nancial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the fi nancial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for its publishing activities. -

Annoucements of Conducting Procurement Procedures

Bulletin No�8(134) February 19, 2013 Annoucements of conducting 002798 Apartments–Maintenance Department of Lviv procurement procedures 3–a Shevchenka St., 79016 Lviv Maksymenko Yurii Ivanovych tel.: (032) 233–05–93 002806 SOE “Makiivvuhillia” Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: 2 Radianska Sq., 86157 Makiivka, Donetsk Oblast www.tender.me.gov.ua Vasyliev Oleksandr Volodymyrovych Procurement subject: code 35.12.1 – transmission of electricity, 2 lots tel.: (06232) 9–39–98; Supply/execution: at the customer’s address, m/u in the zone of servicing tel./fax: (0623) 22–11–30; of Apartments–Maintenance Department of Lviv; January – December 2013 e–mail: [email protected] Procurement procedure: procurement from the sole participant Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: Name, location and contact phone number of the participant: lot 1 – PJSC www.tender.me.gov.ua “Lvivoblenergo” Lviv City Power Supply Networks, 3 Kozelnytska St., 79026 Procurement subject: code 71.12.1 – engineering services (development Lviv, tel./fax: (032) 239–20–01; lot 2 – State Territorial Branch Association “Lviv of documentation of reconstruction of technological complex of skip Railway”, 1 Hoholia St., 79007 Lviv, tel./fax: (032) 226–80–45 shaft No.1 of Separated Subdivision “Mine named after V.M.Bazhanov” Offer price: UAH 22015000: lot 1 – UAH 22000000, lot 2 – UAH 15000 (equipment of shaft for works in sump part)) Additional information: Procurement procedure from the sole participant is Supply/execution: Separated Subdivision “Mine named after V.M.Bazhanov” applied in accordance with paragraph 2, part 2, article 39 of the Law on Public of SOE “Makiivvuhillia”; during 2013 Procurement. -

MB Kupershteyn TOWN of BAR: Jewish Pages Through

1 M. B. Kupershteyn TOWN OF BAR: Jewish Pages Through The Prism Of Time Vinnytsia-2019 2 The publication was carried out with the financial support of the Charity Fund " Christians for Israel-Ukraine” K 92 M. B. Kupershteyn Town of Bar: Jewish Pages Through The Prism Of Time. - Vinnytsia: LLC "Nilan-LTD", 2019 - 344 pages. This book tells about the town of Bar, namely the life of the Jewish population through the prism of historical events. When writing this book archival, historical, memoir, public materials, historical and ethnographic dictionaries, reference books, works of historians, local historians, as well as memories and stories of direct participants, living witnesses of history, photos from the album "Old Bar" and from other sources were used. The book is devoted to the Jewish people of Bar, the history of contacts between ethnic groups, which were imprinted in the people's memory and monuments of material culture, will be of interest to both professionals and a wide range of readers who are not indifferent to the history of the Jewish people and its cultural traditions. Layout and cover design: L. M. Kupershtein Book proofer: A. M. Krentsina ISBN 978-617-7742-19-6 ©Kupers M. B., 2019 ©Nilan-LTD, 2019 3 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 5 HISTORICAL BAR .......................................................................... 7 FROM THE DEPTHS OF HISTORY .................................................. 32 SHTETL .................................................................................... -

1 Mykola Doroshko the Ruling Stratum in the Ukrainian SSR

Mykola Doroshko The Ruling Stratum in the Ukrainian SSR during the Holodomor of 1932–33 In recent times a large body of literature has been published about the initiators of the Holodomor, that is, those who engineered the famine-genocide that took place in Ukraine in 1932–33. The general public is familiar with their names. However, there are far fewer scholarly works devoted to the activities of the immediate executors of Stalin’s directives during the greatest national catastrophe in Ukrainian history—the Communist Party and Soviet nomenklatura (party appointees) of the Ukrainian SSR, which constituted the nucleus of the Kremlin’s colonial administration in the republic. Stalin’s intention to punish the Ukrainian peasants for their resistance to the policy of all-out collectivization by means of a terror-famine depended both on the top ranks of the Soviet Ukrainian leadership and on the utterly compliant local apparatus of power in the republic. Was this apparatus capable of starving the Ukrainian peasants into submission? The state grain-procurement campaigns of 1932 and 1933, the main goal of which was to confiscate grain from the Ukrainian peasantry, were directed by Stanislav Kosior, general secretary of the Central Committee, Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine (CC CP[B]U), Vlas Chubar, head of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Ukrainian SSR, and Hryhorii Petrovsky, head of the All-Ukrainian Central Executive Committee (VUTsVK). In possession of information about the actual state of affairs in Ukrainian agriculture, the leaders of Soviet Ukraine took certain steps to convince the Kremlin leadership that the grain-procurement plans issued from above were unrealistic. -

Journal of Forest Science

JOURNAL OF FOREST SCIENCE VOLUME 66 ISSUE 6 (On–line) ISSN 1805-935X Prague 2020 (Print) ISSN 1212-4834 Journal of Forest Science continuation of the journal Lesnictví-Forestry An international peer-reviewed journal published by the Czech Academy of Agricultural Sciences and supported by the Ministry of Agriculture of the Czech Republic Aims and scope: The journal publishes original results of basic and applied research from all fields of forestry related to European forest ecosystems. Papers are published in English. The journal is indexed in: • Agrindex of AGRIS/FAO database • BIOSIS Citation Index (Web of Science) • CAB Abstracts • CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure) • CrossRef • Czech Agricultural and Food Bibliography • DOAJ (Directory of Open Access Journals) • EBSCO Academic Search • Elsevier Sciences Bibliographic Database • Emerging Sources Citation Index (Web of Science) • Google Scholar • J-Gate • Scopus • TOXLINE PLUS Periodicity: 12 issues per year, volume 66 appearing in 2020. Electronic open access Full papers from Vol. 49 (2003), instructions to authors and information on all journals edited by the Czech Academy of Agricultural Sciences are available on the website: https://www.agriculturejournals.cz/web/jfs/ Online manuscript submission Manuscripts must be written in English. All manuscripts must be submitted to the journal website (https://www. agriculturejournals.cz/web/jfs/). Authors are requested to submit the text, tables, and artwork in electronic form to this web address. It is to note that an editable file is required for production purposes, so please upload your text files as MS Word (.doc) files (pdf files will not be considered). Submissions are requested to include a cover letter (save as a separate file for upload), manuscript, tables (all as MS Word files – .doc), and photos with high (min 300 dpi) resolution (.jpg, .tiff and graphs as MS Excel file with data), as well as any ancillary materials. -

German Occupation of Ukraine: Documents of City Administration of Belaia Tserkov Fond F

German Occupation of Ukraine: Documents of City Administration of Belaia Tserkov Fond F. 2225 The Administration of the Burgomaster of the Town of Belaia Tserkov Opis 1-4; 829 delo 1 Sofiia Kameneva Director of the State Archive of Kyiv Oblast A very important aspect of reexamining the outcome of World War II is updating the source base of Ukrainian archives, above all, the documentary fondy (files) from the period of the Nazi occupation of Ukraine. The introduction of this source base – unique in its novelty and volume – into research practice helps not only eliminate numerous “blank spots” in the history of World War II but also opens up new horizons for further studies. One of the numerous fondy of local self-government bodies from the period of the Nazi occupation of the Kyiv Region stored at the State Archive of Kyiv Region is Fond F. 2225, entitled Upravlenie burgomistra g. Belaia Tserkov [the Administration of the Burgomaster of the Town of Belaia Tserkov], which contains four opisi and 829 items (dela). The Fond’s documentary materials were transferred to the State Archive of Kyiv Region for storage after 1944. In 1945, the first opis was compiled, containing 805 items. In 1947, Opis No. 2 was compiled with 42 items and in 1949, Opis No. 3 with 113 items. In 1962, 31 items arrived from the State Archive of the Town of Belaia Tserkov (Opis No. 4). All of the documents were kept in secret stacks. In accordance with document declassification acts, in 1990 they were moved to open stacks. -

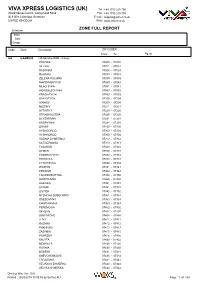

Viva Xpress Logistics (Uk)

VIVA XPRESS LOGISTICS (UK) Tel : +44 1753 210 700 World Xpress Centre, Galleymead Road Fax : +44 1753 210 709 SL3 0EN Colnbrook, Berkshire E-mail : [email protected] UNITED KINGDOM Web : www.vxlnet.co.uk Selection ZONE FULL REPORT Filter : Sort : Group : Code Zone Description ZIP CODES From To Agent UA UAAOD00 UA-Ukraine AOD - 4 days POLISKE 07000 - 07004 VILCHA 07011 - 07012 RADYNKA 07024 - 07024 RAHIVKA 07033 - 07033 ZELENA POLIANA 07035 - 07035 MAKSYMOVYCHI 07040 - 07040 MLACHIVKA 07041 - 07041 HORODESCHYNA 07053 - 07053 KRASIATYCHI 07053 - 07053 SLAVUTYCH 07100 - 07199 IVANKIV 07200 - 07204 MUSIIKY 07211 - 07211 DYTIATKY 07220 - 07220 STRAKHOLISSIA 07225 - 07225 OLYZARIVKA 07231 - 07231 KROPYVNIA 07234 - 07234 ORANE 07250 - 07250 VYSHGOROD 07300 - 07304 VYSHHOROD 07300 - 07304 RUDNIA DYMERSKA 07312 - 07312 KATIUZHANKA 07313 - 07313 TOLOKUN 07323 - 07323 DYMER 07330 - 07331 KOZAROVYCHI 07332 - 07332 HLIBOVKA 07333 - 07333 LYTVYNIVKA 07334 - 07334 ZHUKYN 07341 - 07341 PIRNOVE 07342 - 07342 TARASIVSCHYNA 07350 - 07350 HAVRYLIVKA 07350 - 07350 RAKIVKA 07351 - 07351 SYNIAK 07351 - 07351 LIUTIZH 07352 - 07352 NYZHCHA DUBECHNIA 07361 - 07361 OSESCHYNA 07363 - 07363 KHOTIANIVKA 07363 - 07363 PEREMOGA 07402 - 07402 SKYBYN 07407 - 07407 DIMYTROVE 07408 - 07408 LITKY 07411 - 07411 ROZHNY 07412 - 07412 PUKHIVKA 07413 - 07413 ZAZYMIA 07415 - 07415 POHREBY 07416 - 07416 KALYTA 07420 - 07422 MOKRETS 07425 - 07425 RUDNIA 07430 - 07430 BOBRYK 07431 - 07431 SHEVCHENKOVE 07434 - 07434 TARASIVKA 07441 - 07441 VELIKAYA DYMERKA 07442 - 07442 VELYKA -

U.S.-Ukraine Community Partnerships for Local Government Training and Education Project

U.S.-Ukraine Community Partnerships for Local Government Training and Education Project Award No. 121-A-00-97-00149-00 FINAL REPORT October, 2007 Prepared for United States Agency for International Development Regional Mission for Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova Office of Democratic and Social Transition Prepared by U.S.-Ukraine Foundation 1701 K Street, N.W. Suite 903 Washington, DC 20006 Phone: (202) 223-2228 Fax: (202) 223-1224 E-mail: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………… 3 CPP PROJECT HIGHLIGHTS…………………………………………………………. 4 PROJECT COMPONENTS………………………………………………………. 5 I. U.S.-Ukraine Partnerships………………………………………………………... 5 Artemivsk-Omaha, NE…………………………………………………............ 7 Berdiansk-Lowell, MA…………………………………………………………. 8 Cherkasy-Des Moines, IA……………………………………………………… 9 Kalush-Little Rock, AR……………………………………………………….... 10 Kamianets-Podilsky-Athens, GA………………………………………………. 11 Kharkiv-Cincinnati, OH………………………………………………………... 12 Komsomolsk-Ithaca, NY……………………………………………………….. 12 Krasnodon-Birmingham, AL………………………………………………….... 14 Nikopol-Toledo, OH……………………………………………………………. 14 Pervomaisk-Kansas City, MO………………………………………………….. 15 Romny-Lognview, TX………………………………………………………….. 15 Rubizhne-Louisville, KY……………………………………………………….. 16 Slavutych-Richland, WA……………………………………………………….. 17 Svitlovodsk-Springfield, IL…………………………………………………….. 17 II. Cluster Partnerships Model-Best Practices…………………………………….... 18 Partnerships – Lessons Learned……………………………………………………………. 21 III. Regional Training Centers (RTC) Activity: Overview…………………….......... 27 -

Adas Israel Congregation

Adas Israel Congregation March/Adar I–Adar II Highlights: ChronicleJMCW Wins Slingshot Award 3 Kol HaOlam A Cappella 5 Purim 5776 6 Community Passover Seder 8 March MakomDC 10 Ma Tovu: Sandy Eskin 18 Purim is a holiday urging each of us to witness our lives from an alternate reality; a day in which up becomes down, right becomes left, and life becomes laughter. Chag Purim Sameach! Chronicle • March 2016 • 1 The Chronicle Is Supported in Part by the Ethel and Nat Popick Endowment Fund clergycorner From the President By Debby Joseph Senior Rabbi Gil Steinlauf ‘Where Is God now?’ I hear this question a lot. Particularly from people who are going through times of personal crisis. When we go through crises, like loss, illness, or betrayal, we can feel abandoned by God. We can feel abandoned by everyone whom we hoped would be there for us, even when those closest to us are trying their hardest to be there for us. Sometimes, when trying to Adas Israel is bustling with activity at all comfort or help someone in crisis, we don’t choose the right words when times every day. Our community is grow- faced with another’s loss and pain. Our words, however well meaning, can ing, with members who are engaged and make even God feel far away. involved with studying, creating, and caring Judaism is a religion that focuses on words, ideas, expressions, and actions. for one another. Our clergy team inspires and When a word is present in the Torah, it has infinite meaning. And when a word challenges us; teachers and staff motivate is missing, that, too, has infinite meaning. -

Mariia KAZMYRCHUK

Mariia KAZMYRCHUK UDC 94(=411.16)(477.4)”18/19” DOI: 10.24919/2519-058x.15.204970 Mariia KAZMYRCHUK PhD hab. (History), Associate Professor of the Ethnology and Local History Department, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, 60 Volodymyrska Street, Kyiv, Ukraine, postal code 01033 ([email protected]) ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8877-4489 Марія КАЗЬМИРЧУК доктор історичних наук, доцент кафедри етнології та краєзнавства Київського національного університету імені Тараса Шевченка, вул. Володимирська, 60, м. Київ, Україна, 01033 ([email protected]) Бібліографічний опис статті: Kazmyrchuk, M. (2020). Jewish landownership and interethnic relations in Kyiv Governorate at the end of the XIXth and the beginning of the XXth centuries. Skhidnoievropeiskyi Istorychnyi Visnyk [East European Historical Bulletin], 15, 72–79. doi: 10.24919/2519-058x.15.204970 JEWISH LANDOWNERSHIP AND INTERETHNIC RELATIONS IN KYIV GOVERNORATE AT THE END OF THE ХІХth AND THE BEGINNING OF THE ХХth CENTURIES Abstract. The aim of the article is to analyze possible modes, which were used by the Jews to own a plot of land and estate property in Kyiv Governorate at the end of the ХІХth century and the beginning of the ХХth century, to explain a negative attitude towards Jewish population by the growing struggle for the landownership based on the archival sources. The research methodology of the article is based on general historical methods such as typological and statistical; as well comparative and structural analyses have been used by the author. The Scientific Novelty. The article is the first attempt to discover the modes and schemes to own a land property by the Jews, who tried to avoid the law restrictions of the Russian Empire, and to explain other ethnical groups’ negative attitude towards the Jewish population in Kyiv Governorate by means of getting a land property, which was a symbol of freedom and welfare.