JBSC 2019 Proceedings DEF.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belfast Investment Guide

SPONSORSHIP Cannes, France 12th-14th March 2019 Investment Guide 2020 @BelfastMIPIM InvestInBelfast.com/MIPIM 3 Contents Welcome 3 Welcome Belfast at a Glance 4 Suzanne Wylie Chief Executive, 6 Reasons to Invest in Belfast Belfast City Council Key Sectors Belfast is a city of exceptional possibilities. Our city has has seen over 2.5 million sq ft of floor space of office 7 seen an impressive trajectory of development across accommodation completed or under construction; almost sectors ranging from hotels, office accommodation, 5,000 purpose built student accommodation beds have Belfast Region City Deal cultural venues and visitor experiences, education space been completed or under construction; and to support 10 and student and residential accommodation. the growing tourism market, 1,500 hotel beds have been completed; and approximately 5,000 residential units Northern Ireland Real Estate Market We’re committed to taking Belfast to the next level. for the city centre are at various stages in the planning 12 The £850 million Belfast Region City Deal will see process. investment in innovation and digital, tourism and Opportunities regeneration, infrastructure and employability and skills Additionally, there are over 40 acres of major mixed-use 14 across 22 projects. These projects will be underpinned regeneration schemes currently in progress, including by investment in employability and skills which will Weavers Cross (a major transport-led regeneration accelerate inclusive economic growth, significantly project) and significant waterfront developments. increase GVA and create up to 20,000 new and better jobs across the region. As a city with unrivalled growth potential, we look towards an exciting future for all in which to live, work, learn, play Strong collaborative leadership is key - and we’re leading and invest. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Council, 07/01/2019 18:00

Public Document Pack BELFAST CITY COUNCIL SUMMONS TO ATTEND THE MONTHLY MEETING OF THE COUNCIL TO: THE LORD MAYOR, ALDERMEN AND THE COUNCILLORS OF BELFAST CITY COUNCIL Notice is hereby given that the monthly meeting of the Council will be held in the Council Chamber, City Hall, Belfast on Monday, 7th January, 2019 at 6.00 p.m., for the transaction of the following business: 1. Summons 2. Apologies 3. Declarations of Interest 4. Minutes of the Council (Pages 1 - 14) a) Amendment to Standing Orders To affirm the Council’s decision of 3rd December to amend Standing Order 37(d) to give effect to the Licensing Committee having delegated authority to determine applications under the Houses in Multiple Occupation Act (Northern Ireland) 2016. 5. Official Announcements 6. Request to Address the Council To consider a request from Mr. Conor Shields, Save CQ Campaign, to address the Council in relation to the motion on Tribeca Belfast being proposed by Councillor Reynolds. 7. Strategic Policy and Resources Committee (Pages 15 - 66) 8. People and Communities Committee (Pages 67 - 114) 9. City Growth and Regeneration Committee (Pages 115 - 162) 10. Licensing Committee (Pages 163 - 174) 11. Planning Committee (Pages 175 - 200) 12. Brexit Committee (Pages 201 - 206) 13. Notices of Motion a) Inter-Generational Loneliness Proposed by Councillor Mullan, Seconded by Alderman Spence, “This Council notes with concern the impact that inter-generational loneliness and social isolation is having across the City. The Council recognises the good work already being done in the Council to address these problems but acknowledges that more needs to be done. -

Asset Management in Rail Public Transport Sector and Industry 4.0 Technologies

Bruno Teixeira Cavalcante de Magalhães Daniel Machado dos Santos Débora Cristina Faria de Araújo Gustavo Henrique Lucas Jaquie ASSET MANAGEMENT IN RAIL PUBLIC TRANSPORT SECTOR AND INDUSTRY 4.0 TECHNOLOGIES Brasília, Brazil November 2020 Bruno Teixeira Cavalcante de Magalhães Daniel Machado dos Santos Débora Cristina Faria de Araújo Gustavo Henrique Lucas Jaquie A Final Educational Project Submitted to Deutsche Bahn AG in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Rail and Metro Rail Transportation Systems Management Certificate Program This Final Educational Project was prepared and approved under the direction of the DB Rail Academy, Mr. Marcus Braun. Brasilia, Brazil November 2020 ABSTRACT Industry 4.0 is the concept adopted to refer to new technologies that have been deeply impacting the entire industry, in practically all sectors. The development of technologies associated with the internet of things (IoT) and intelligent systems is driving the industry towards digital transformation. In this scenario, many possibilities arise for the rail public transport sector, mainly for Asset Management, considering that Asset Management represents a significant portion of the operator's efforts and costs to keep the commercial operation running. This work presents the traditional asset management concepts currently used in the public transport sector on rails, as well as some opportunities for using Industry 4.0 technologies in this sector. Then, a methodology for implementing these opportunities is proposed, with the agile methodology being suggested as an implementation strategy, considering a cost- benefit analysis, risk analysis, project plan, implementation plan and financial plan. It is expected that the ideas presented in this work can stimulate other sectors of the industry to move towards Industry 4.0, which is an inevitable trend and will certainly determine in the medium and long term who will survive in an increasingly competitive environment. -

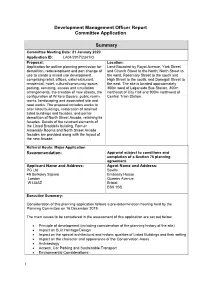

Development Management Officer Report Committee Application

Development Management Officer Report Committee Application Summary Committee Meeting Date: 21 January 2020 Application ID: LA04/2017/2341/O Proposal: Location: Application for outline planning permission for Land Bounded by Royal Avenue, York Street demolition, redevelopment and part change of and Church Street to the North; North Street to use to create a mixed use development the west; Rosemary Street to the south and comprising retail, offices, cafe/restaurant, High Street to the south; and Donegall Street to residential, hotel, cultural/community space, the east. The site is located approximately parking, servicing, access and circulation 300m west of Laganside Bus Station, 300m arrangements, the creation of new streets, the northeast of City Hall and 900m northwest of configuration of Writers Square, public realm Central Train Station. works, landscaping and associated site and road works. The proposal includes works to alter listed buildings, restoration of retained listed buildings and facades, and partial demolition of North Street Arcade, retaining its facades. Details of the retained elements of the Listed Braddells building, Former Assembly Rooms and North Street Arcade facades are provided along with the layout of the new Arcade. Referral Route: Major Application Recommendation: Approval subject to conditions and completion of a Section 76 planning agreement. Applicant Name and Address: Agent Name and Address: PG Ltd Savills 49 Berkeley Square Embassy House London Queens Avenue W1J5AZ Bristol BS8 1SB Executive Summary: Consideration of this planning application follows a pre-determination hearing held by the Planning Committee on 16 December 2019. The main issues to be considered in the assessment of this application are set out below. -

Redalyc.The Maturity of Rail Freight Logistics Service Providers in Brazil

Production ISSN: 0103-6513 [email protected] Associação Brasileira de Engenharia de Produção Brasil Farias Bueno, Adauto; Hazin Alencar, Luciana The maturity of rail freight logistics service providers in Brazil Production, vol. 26, núm. 2, abril-junio, 2016, pp. 359-372 Associação Brasileira de Engenharia de Produção São Paulo, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=396745849009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Production, 26(2), 359-372, abr./jun. 2016 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0103-6513.178414 The maturity of rail freight logistics service providers in Brazil Adauto Farias Buenoa*, Luciana Hazin Alencarb** aUniversidade do Estado de Mato Grosso, Barra do Bugres, MT, Brazil bUniversidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, PE, Brazil *[email protected], **[email protected] Abstract This study analyzes the maturity of three rail freight Logistics Service Providers (LSPs) in Brazil in a population of seven operators. After an exploratory review of the existing literature and research documents, a structured questionnaire based on the Supply Chain Capability Maturity Model S(CM)2 was applied. The study measured an overall average level, given in S(CM)2, as Managed, meaning that the managerial development standard of the logistics agents was at an intermediate level. The results showed that maturity was related to the size of the LSP and the complexity of the organizational management. These findings can support the development of policies and strategies for the improvement and adoption of practices that best lead to gains in competitiveness for both LSPs and the Supply Chains (SCs) that require their services. -

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO Faculdade De Filosofia, Letras E

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas Departamento de Geografia TRABALHO DE GRADUAÇÃO INDIVIDUAL EM GEOGRAFIA De espaço de circulação a objeto de uso turístico: A Estrada de Ferro do Paraná CRISTINA ASSIS PARADA N° USP 7245910 - NOTURNO São Paulo 2016 CRISTINA ASSIS PARADA De espaço de circulação a objeto de uso turístico: A Estrada de Ferro do Paraná Trabalho de Graduação Individual apresentado ao Departamento de Geografia da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo para obtenção do título de Bacharela em Geografia Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Rita de Cássia Ariza da Cruz São Paulo 2016 AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço, antes de qualquer palavra, meus pais, Sonia e Gim, minhas irmãs, Michelli e Priscilla. Pelo amor que nos mantem sempre unidos, pela força que nos faz acreditar em sermos tudo o que somos porque construímos à nossa maneira. Agradeço ao meu grande companheiro Heitor Faria Rodrigues. Em tudo me fez melhor e me fez acreditar. Aquilo que é invisível aos nossos olhos, invisível às palavras. Agradeço a toda minha família e a família que ganhei com o Heitor. Pelas palavras, olhares, desdobramentos, orações, pensamentos bons, força. Tudo isso me fez resistir àquilo que precisei passar. E passou. Aos meus amigos que estiveram sempre próximos. Aos amigos que a Universidade de São Paulo me confiou, amigos da Graduação, amigos extraídos do trabalho. A todos os Professores que tive contato em minha graduação, essenciais em minha formação. A Professora Rita, minha orientadora, não apenas por ter acreditado nesta pesquisa, mas também pelo apoio e a sua maneira de me fazer não desistir dos meus sonhos. -

Our Outlook Is Simple We Inform Your Future

OUR OUTLOOK IS SIMPLE WE INFORM YOUR FUTURE 2019 Contents LISNEY OUTLOOK 2019 00 01 02 INTRO RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT & NEW HOMES 03 04 05 INVESTMENT OFFICES INDUSTRIAL 06 07 08 LICENSED RETAIL CORK PREMISES 09 10 11 BELFAST LISNEY IN LISNEY IN PICTURES NUMBERS Simply informing We look forward to working with you in 2019 to find, create and secure value 4 | LISNEY OUTLOOK 2019 your future AS THE YEAR BEGINS THERE IS A NERVOUSNESS IN SOME MARKETS WITH THE ‘KNOWN UNKNOWN’ OF BREXIT LOOMING LARGE AT THE END OF THE FIRST QUARTER The bull stock market ran out of and quality service that they need steam in the second half of 2018. That to make good decisions. In 2018 type of inflexion often points capital we acquired Morrissey’s, the market to perceived safer havens that include leaders in licensed and leisure property, property. Irish property has been on and have integrated them into Lisney an upward trajectory for six years. The to give our clients a greater range and residential market while still suffering depth of service. We will develop this from an undersupply has paused for further along with some other service breath in the middle and upper end lines in 2019. of the market which we expect to We will open a new residential office in move ahead again in 2019. Market Dalkey late this quarter of 2019 to better interventions in the lending market serve one of our key markets. Working need to be addressed to allow alongside the traditional network of markets to function more normally. -

Midsummer Retail Report 2019

Midsummer Retail Report 2019 IS THIS THE END OF EXECUTIVE RETAIL SHOPPING WITH REGIONAL THE MARKET MONEY THE GOLDEN AGE OF KNOWLEDGE FOOD CONTACTS SUMMARY REIMAGINED A CONSCIENCE UPDATES ONLINE RETAILING? < > EXECUTIVE SUMMARY After an unprecedented year of turmoil, the UK retail sector and the property market that it supports is having to reinvent itself. IS THIS THE END OF EXECUTIVE RETAIL SHOPPING WITH REGIONAL THE MARKET MONEY THE GOLDEN AGE OF KNOWLEDGE FOOD CONTACTS SUMMARY REIMAGINED A CONSCIENCE UPDATES ONLINE RETAILING? < > EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OUR LATEST MIDSUMMER KEY FINDINGS RETAIL REPORT LOOKS AT ● The ‘Golden Age’ of online retailing is coming to an end. ● Major retail development can no longer play the kind Online retailers will be increasingly compelled to engage of central role in regeneration that it has for the past THE CHANGES IN STRATEGIC with physical shopping environments to stay competitive. 50 years. This poses the question as to what will become the economic focal point of urban environments. DIRECTION THAT THE SECTOR ● At £1,868 per person, the UK retail ecommerce expenditure per capita is higher than in any other G20 market, with ● The Government needs to do more to support the Retail WILL HAVE TO FACE IN ORDER both online advertising expenditure and internet retail Industry which employs 10% of the UK workforce and TO REMAIN RELEVANT expenditure almost trebling since 2010. generates £400bn of sales annually. ● Environmental concerns over the impact of online shopping ● The war on plastic, the rise of veganism and growing AND VIABLE. delivery may eventually lead to the introduction of a opposition to the waste incurred by ‘fast fashion’ are ‘suburban congestion charge’. -

Belfast Report October 2019

Belfast Report October 2019 Max Thorne, Narup Chana, Thomas Domballe, Kat Stenson, Laura Harris, Bryony Hutchinson and Vikkie Ware MRP GROUP 11-15 High 1Street, Marlow, SL7 1AU Contents Executive Summary 3 Belfast Profile 3 Economic Overview 4 Developments 6 Transport 8 Leisure Overview 9 Tourism 10 Supply of Rooms 11 Annual Occupancy Room Figures 11 Current Hospitality Market 12 The Team 13 2 Executive Summary Belfast is a cosmopolitan capital city with a successful tourist industry and thriving business district that has seen worldwide attention. Recent feats that have garnered attention include the production of Game of Thrones and the Titanic Belfast. Due to the exposure, many businesses have invested in the city after realising the low cost of office space and opportunity’s for innovation. Belfast Profile Belfast is the capital of Northern Ireland and played a vital role in the early 19th century as a major port which then was joined by shipbuilding. As of 2017, Belfast had a city population of over 340k and a wider regional population of over 1m. The city has a young population, with 43% of the population under the age of 30. A city attracts a young population as a result of high quality, affordable housing, a good quality of life and availability of jobs. Belfast has all of these assets, and the significant investment in the city will ensure that the population and economy will grow. In 2018, there were 23 new company investments which created over 1k new jobs and 80% of new investors reinvested in the region. 3 Economic Overview Belfast is a key driver in Northern Ireland’s economy and the second fastest knowledge economy region in the UK, demonstrating the city’s importance as a business destination. -

Projection of Macroeconomic Impacts on the Toll Plazas Waiting Time Queueing: a Case Study in Brazil

International Journal of Research in Engineering and Science (IJRES) ISSN (Online): 2320-9364, ISSN (Print): 2320-9356 www.ijres.org Volume 4 Issue 3 ǁ March. 2016 ǁ PP.68-80 Projection of Macroeconomic Impacts on The Toll Plazas Waiting Time Queueing: A Case Study In Brazil Mariana Gonçalves de Carvalho Wolff*, Marco Antonio Farah Caldas Industrial Engineering, Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niterói, Brazil. Rua Passos da Pátria, 156, Bloco D, Sala 309, São Domingos, Niterói, Brazil. SUMMARY:- This study aims to understand the flows of vehicular traffic in a toll plaza impacted by macroeconomic events. The study provides the traffic demand of commercial and small vehicles on a Brazilian highway until the year 2020. This Highway plays an important role for the oil industry and the development of the region depends mostly on it. The population, the region's Gross Domestic Product and oil production are considered as explanatory variables. The data used is divided by the toll plaza, vehicle type and area of influence. A simulation model for discrete events is used based on the actual scenario and future events. The model concludes that the amount of commercial vehicles will rise significantly, generating an increase in the queue waiting time of the toll plazas, going up to nineteen minutes. To reduce the stakeholders impact the study suggests some steps for planning the highway in the medium term. Keywords:- logistics bottleneck; simulation; macroeconomic development; transportation planning; linear regression. I. INTRODUCTION The country´s economic development needs a quality infrastructure that allows a flow of vehicles and people and also allows developing less accessible areas, facilitating their access to major cities and ports. -

Belfast Crane Survey 2020 Contents

Ready to accelerate? Belfast Crane Survey 2020 Contents Foreword 01 Development snapshot 02 Key findings 03 Residential 04 Office 10 Student, education and research 16 Hotel, retail and leisure 20 Development map 28 Endnotes 30 Contacts 31 hen? here? hat? Data for the Crane Survey was The City Core, Waterfront, Titanic Developers building new schemes or recorded between 11 January 2019 and Quarter, Transport Hub, Inner North, undertaking significant refurbishments 13 December 2019. Linen Quarter and Southern Fringe. exceeding any of the following sizes: office – 10,000 sq ft; retail and leisure 10,000 sq ft; residential property – 25 units; education, healthcare and research – 10,000 sq ft; hotel – 35 rooms. Titanic Quarter hy? Inner North A report that measures the volume of development taking place across central Belfast and its impact. Property types include residential, office, leisure, hotels, retail, student accommodation, education and research facilities, and healthcare. City Core Waterfront How? Research for this report was undertaken by Deloitte’s Northern Transport Hub Ireland team, based in Belfast. The Linen Quarter Deloitte Real Estate team have also been closely involved in the development of Belfast over recent years. In addition to our in-house knowledge and field research we have Southern used a variety of sources to collate and Fringe validate our research. These sources include the Northern Ireland Planning Portal, local media and trade publications, and construction and development industry contacts. Ready to accelerate? | Belfast Crane Survey 2020 Foreword Belfast remains open for business despite a year filled with uncertainty. Residential development within the city centre continues to be a hot topic of debate – mainly because although many stakeholders want it to happen, progress is slow. -

The Feasibility Study for Establishment of Passenger Rail in the Metropolitan Region of Belo Horizonte / Brazil

The Feasibility Study for Establishment of Passenger Rail in the Metropolitan Region of Belo Horizonte / Brazil Marcelo Franco PORTO School of Engineering, Federal University of Minas Gerais Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil and Luiz Carlos de Jesus MIRANDA Nilson Tadeu Ramos NUNES Cássio E. dos SANTOS Jr. School of Engineering, Federal University of Minas Gerais Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil ABSTRACT There are investments to existing lines disabled or in poor condition, as well as incentives for redeployment of passenger The rail transportation, either of passengers or cargo, is transport in sections where only the cargo remained. These essential to the country's economic growth. Due to a number of lines could play a strategic role in the mobility issue because factors, in particular, severe mobility problems experienced by they are in metropolitan regions or make the connection large cities and a demand for urban transport systems and between cities large and medium-sized with a large demand for suburban high capacity transport on rails going through a high capacity transportation. period of recovery with new investments being announced both for the construction of new railway sections, as for reclamation 2. HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT and re-adaptation of existing railway networks. In this context, the liability of decades without investment, necessitates a The railroads arrived in Brazil still in the Imperial period. A rational use of available resources and agile enabling to country special law of 1852, which established the security interest on develop projects for the sector rapidly and consistently. This the capital invested in railway construction, besides other paper presents a proposal that aims to make it easier to review advantages is it possible to leverage the construction of the first and registration of a railroad.