Department of Political Science University of Peshawar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sb List for 19.11.2018(Monday)

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR MONDAY, 19 NOVEMBER, 2018 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE Court No: 1 ANNOUNCEMENT 1. RFA Wazir Ahmad Khan Khurshid Ahmed Khattak, 196/2005(With V/s (Date By Court) Muhammad Amin Khattak Lachi CMs Reayat Khan Khattak 100,228/09,C.ms.4 Abdul Samad Khan, Syed Mir 75,409/12) Muhammad, Khalid Khan, M.Amin Khattak, Arshad Jamal Qureshi i RFA 181/2005 Cheif Editor Daily Statesman Ijaz Anwar V/s Damages, Rs.20 million Senior Part Reayat Khan Khattak Abdul Samad Khan, Adeel Anwar Jehangir, , M.Amin Khattak, Adnan Khattak, Ibrahim Shah ii RFA 249/2005 With Attiqur Rehman M.Amin Khattak V/s CMs 101-P/2009 Reayat Khan Khattak Ijaz Anwar, Abdul Samad Khan, Khurshid Ahmed Khattak, Arshad Jamal Qureshi iii RFA 84/2011 with Muhamamd Zareen Arshad Jamal Qureshi V/s C.M.406/11 Wazir Ahmad Khan and others Muhammad Amin Khattak, Ijaz Anwar, Abdul Samad Khan Zaida, Muhammad Amin Khattak Lachi, Adnan Khattak, Arshad Jamal MOTION CASES 1. Cr.M(TA) Farhad Fazal Shah Mohmand 87/2018() V/s (Date By Court) The State AG KPK 2. CM(TA) 85/2018() Sharif Khan Muhammad Hasnain V/s Late Sher Dil Khan 3. CM(TA) 86/2018() Abbottabad International Sardar Saadat Ali Medical College V/s Federation of Pakistan MIS Branch,Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 95 Report Generated By: C f m i s _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR MONDAY, 19 NOVEMBER, 2018 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE Court No: 1 MOTION CASES 4. -

Herat Security Dialogue Short Bios of the Presenters and Moderators

Herat Security Dialogue Short Bios of the Presenters and Moderators Abdullah Ahmadzai Abdullah Ahmadzai is The Asia Foundation’s County Representative in Afghanistan. He served as the Deputy Country Representative from 2012 to 2014. He was formerly Chief Electoral Officer for the Independent Election Commission (IEC) of Afghanistan. Prior to his position with the IEC, from June 2006 to October 2009, Ahmadzai worked with the Foundation, serving under the Support to Center of Government project in Afghanistan. Between 2004 and 2006, he held positions with the UN under the Joint Electoral Management Body Secretariat (JEMBS), first as an Area Manager and then as Chief of Operations. From 2003-2004, Ahmadzai was actively involved with the Afghanistan Constitution Commission which was mandated by the 2001 Bonn Agreement to draft a new constitution for the country. Under the Commission, he assisted with the Emergency Loya Jirga and later the drafting of the constitution which was formally adopted in January 2004. He has a Bachelor’s degree in Information Technology from Brains Degree College in Peshawar, Pakistan, in addition to several workshop certificates earned through Harvard and Georgetown Universities, and the International Foundation for Electoral Services. Abdul Ghafoor Liwal Abdul Ghafoor Liwal is the Special Advisor to the President of National Unity Government for Tribal and Border Affairs. Prior to this, he worked as a Deputy Minister of Tribal and Border Affairs. He has a Bachelor’s Degree in Literature from Kabul University and two Masters, one in Journalism from Maryland University (2004-2005), and another in Pashtu from Kabul University in 2008. -

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and Confrontationist Power Politics in Pakistan : JRSP, Vol

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and Confrontationist Power Politics in Pakistan : JRSP, Vol. 58, No 2 (April-June 2021) Ulfat Zahra Javed Iqbal Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and the Beginning of Confrontationist Power Politics in Pakistan 1971-1977 Abstract: This paper mainly explores the genesis of power politics in Pakistan during 1971-1977. The era witnessed political disorders that the country had experienced after the tragic event of the separation of East Pakistan. Bhutto’s desire for absolute power and his efforts to introduce a system that would make him the main force in power alienated both, the opposition and his colleagues and supporters. Instead of a democratic stance on competitive policies, he adopted an authoritarian style and confronted the National People's Party, leading to an era characterized by power politics and personality clashes between the stalwarts of the time. This mutual distrust between Bhutto and the opposition - led to a coalition of diverse political groups in the opposition, forming alliances such as the United Democratic Front and the Pakistan National Alliance to counter Bhutto's attempts of establishing a sort of civilian dictatorship. This study attempts to highlight the main theoretical and political implications of power politics between the ruling PPP and the opposition parties which left behind deep imprints on the history of Pakistan leading to the imposition of martial law in 1977. If the political parties tackle the situation with harmony, a firm democracy can establish in Pakistan. Keywords: Pakhtun Students Federation, Dehi Mohafiz, Shahbaz (Newspaper), Federal Security Force. Introduction The loss of East Pakistan had caused great demoralization in the country. -

Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates

Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates Syeda Amna Sohail Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates THESIS To obtain the degree of Master of European Studies track Policy and Governance from the University of Twente, the Netherlands by Syeda Amna Sohail s1018566 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Robert Hoppe Referent: Irna van der Molen Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Motivation to do the research . 5 1.2 Political and social relevance of the topic . 7 1.3 Scientific and theoretical relevance of the topic . 9 1.4 Research question . 10 1.5 Hypothesis . 11 1.6 Plan of action . 11 1.7 Research design and methodology . 11 1.8 Thesis outline . 12 2 Theoretical Framework 13 2.1 Introduction . 13 2.2 Jakubowicz, 1998 [51] . 14 2.2.1 Communication values and corresponding media system (minutely al- tered Denis McQuail model [60]) . 14 2.2.2 Different theories of civil society and media transformation projects in Central and Eastern European countries (adapted by Sparks [77]) . 16 2.2.3 Level of autonomy depends upon the combination, the selection proce- dure and the powers of media regulatory authorities (Jakubowicz [51]) . 20 2.3 Cuilenburg and McQuail, 2003 . 21 2.4 Historical description . 23 2.4.1 Phase I: Emerging communication policy (till Second World War for modern western European countries) . 23 2.4.2 Phase II: Public service media policy . 24 2.4.3 Phase III: New communication policy paradigm (1980s/90s - till 2003) 25 2.4.4 PK Communication policy . 27 3 Operationalization (OFCOM: Office of Communication, UK) 30 3.1 Introduction . -

Shamanic Wisdom, Parapsychological Research and a Transpersonal View: a Cross-Cultural Perspective Larissa Vilenskaya Psi Research

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 15 | Issue 3 Article 5 9-1-1996 Shamanic Wisdom, Parapsychological Research and a Transpersonal View: A Cross-Cultural Perspective Larissa Vilenskaya Psi Research Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Vilenskaya, L. (1996). Vilenskaya, L. (1996). Shamanic wisdom, parapsychological research and a transpersonal view: A cross-cultural perspective. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 15(3), 30–55.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 15 (3). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies/vol15/iss3/5 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHAMANIC WISDOM, PARAPSYCHOLOGICAL RESEARCH AND A TRANSPERSONAL VIEW: A CROSS-CULTURAL ' PERSPECTIVE LARISSA VILENSKAYA PSI RESEARCH MENLO PARK, CALIFORNIA, USA There in the unbiased ether our essences balance against star weights hurled at the just now trembling scales. The ecstasy of life lives at this edge the body's memory of its immutable homeland. -Osip Mandelstam (1967, p. 124) PART I. THE LIGHT OF KNOWLEDGE: IN PURSUIT OF SLAVIC WISDOM TEACHINGS Upon the shores of afar sea A mighty green oak grows, And day and night a learned cat Walks round it on a golden chain. -

Single Bench List for 02.03.2018

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR FRIDAY, 02 MARCH, 2018 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH Court No: 2 MOTION CASES 1. CM Corr Waseem Akram Ishtiaq Ahmad 54/2018(in BA V/s 19/2018) The State and Others 2. W.P 655/2018() Zafar Ali Sabitullah Khan Khalil V/s Lal Khan and Others 3. Cr.A 889/2017() Fawad Ali Anwar Hussain V/s (Date By Court) The State etc 4. Cr.M(BCA) Malang LRS of Deceased Qazi Intikhab Ahmad 2766/2017() Sakheem Gul V/s Sajjad and Others 5. C.R 525/2016 Pir Hashmat Ali & Others Raja Muhammad Ijaz (Others) with V/s o/n(Declaration) Muhammad Hussain & Others Mukamil Shah Taskeen 6. C.R 597/2017 with Ali Abbas Zafar Ahmad Awan cm. 961/2017() V/s Mst. Naeema Kausar & Others MIS Branch,Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 52 Report Generated By: C f m i s _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR FRIDAY, 02 MARCH, 2018 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH Court No: 2 MOTION CASES 7. C.R 78/2018 with Majid and Others Ayaz Khan Khalil cm. 181/2018 (m)() V/s Muhammad Yousaf etc 8. C.R 100/2018 with Govt of KPK and Others Advocate General c.m 145-P/2018() V/s Saleem Numan and Others 9. Cr.R Naqeeb Ullah Mudassir Ali Bangash 149/2016(Enhance V/s the sentence) Hafeez Ullah and another Abid Ali, A.A.G 10. C.R 700/2014 Mst. Kiran Zia Ur Rehman (Others)(Against V/s decree(Stay Mohib Ullah Khan and another Mukamil Khan, Naveed ur confirmed on Rehman, Farmanullah Sailab, 27/10/14)) Farooq Malik 11. -

Quaid-I-Azam's Visit to the Southern Districts of NWFP

Quaid-i-Azam’s Visit to the Southern Districts of NWFP 1 ∗ ∗∗ Muhammad Aslam Khan & Muhammad Shakeel Ahmad Abstract In this paper an attempt has been made to explore the detailed achievements of Quaid-i-Azam’s visit to southern NWFP i.e Kohat, Bannu and DI. Khan. Historians always focused on Quiad’s visit to central NWFP like Islamia College Peshawar, Edward College Peshawar, Landikotal and other places, but they have missed to highlight his visit to southern NWFP. Quaid-i-Azam visited all the three Southern districts Kohat, Bannu and Dera Ismail Khan of NWFP on very short notice. Therefore no proper security arrangements were made and media did not give proper coverage to his visit. The details of Quaid’s visit to Southern NWFP is still unexplored by historians. This paper is a new addition on the existing literature on Quaid-i-Azam. Keywords: Quaid-i-Azam, NWFP, Khyber Pukhtunkhwa, Pakistan To Pakistanis, Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, is their George Washington, their de Gaulle and their Churchill . Quaid-i-Azam visited NWFP thrice in his life span. For the first time, Quaid arrived in Peshawar on Sunday, the 18th of October 1936 2 and stayed for a week from 18th to the 24th of October at the Mundiberi residence of Sahibzada Abdul Qayum Khan 3. The political situations in the province were quite blurred at that time. Quaid visited Edward College and Islamia College Peshawar. He listened to the opinions of people from all shades of life and had friendly exchange of views with all of them. -

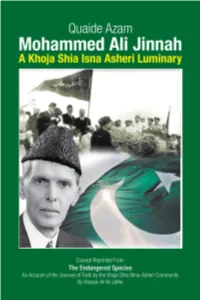

Quide Azam Monograph V3

Quaide Azam Mohammed Ali Jinnah: A Khoja Shia Ithna Asheri Luminary ndia became Independent in 1947 when the country was divided as India and Pakistan. Four men played a significant role in I shaping the end of British rule in India: The British Viceroy, Lord Louis Mountbatten, the Indian National Congress leaders Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, and the Muslim League leader, Mohamed Ali Jinnah. Jinnah led the Muslims of India to create the largest Muslim State in the world then. In 1971 East Pakistan separated to emerge as Bangladesh. Much has been written about the first three in relative complimentary terms. The fourth leading player, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, founding father of Pakistan, lovingly called Quaid-e-Azam (the great leader) has been much maligned by both Indian and British writers. Richard Attenborough's hugely successful film Gandhi has also done much to portray Jinnah in a negative light. Excerpt from Endangered Species | 4 The last British Viceroy, Lord Louis Mountbatten, spared no adjectives in demonizing Jinnah, and his views influenced many writers. Akber S. Ahmed quotes Andrew Roberts from his article in Sunday Times, 18 August,1996: “Mountbatten contributed to the slander against Jinnah, calling him vain, megalomaniacal, an evil genius , a lunatic, psychotic case and a bastard, while publicly claiming he was entirely impartial between Jinnah’s Pakistan and Nehru’s India. Jinnah rose magisterially above Mountbatten’s bias, not even attacking the former Viceroy when, as Governor General of India after partition, Mountbatten tacitly condoned India’s shameful invasion of Kashmir in October 1947.”1 Among recent writers, Stanley Wolport with his biography: Jinnah of Pakistan, and Patrick French in his well researched Freedom or Death analyzing the demise of the British rule in India come out with more balanced portrayal of Jinnah - his role in the struggle for India’s independence and in the creation of Pakistan. -

Pakistan Courting the Abyss by Tilak Devasher

PAKISTAN Courting the Abyss TILAK DEVASHER To the memory of my mother Late Smt Kantaa Devasher, my father Late Air Vice Marshal C.G. Devasher PVSM, AVSM, and my brother Late Shri Vijay (‘Duke’) Devasher, IAS ‘Press on… Regardless’ Contents Preface Introduction I The Foundations 1 The Pakistan Movement 2 The Legacy II The Building Blocks 3 A Question of Identity and Ideology 4 The Provincial Dilemma III The Framework 5 The Army Has a Nation 6 Civil–Military Relations IV The Superstructure 7 Islamization and Growth of Sectarianism 8 Madrasas 9 Terrorism V The WEEP Analysis 10 Water: Running Dry 11 Education: An Emergency 12 Economy: Structural Weaknesses 13 Population: Reaping the Dividend VI Windows to the World 14 India: The Quest for Parity 15 Afghanistan: The Quest for Domination 16 China: The Quest for Succour 17 The United States: The Quest for Dependence VII Looking Inwards 18 Looking Inwards Conclusion Notes Index About the Book About the Author Copyright Preface Y fascination with Pakistan is not because I belong to a Partition family (though my wife’s family Mdoes); it is not even because of being a Punjabi. My interest in Pakistan was first aroused when, as a child, I used to hear stories from my late father, an air force officer, about two Pakistan air force officers. In undivided India they had been his flight commanders in the Royal Indian Air Force. They and my father had fought in World War II together, flying Hurricanes and Spitfires over Burma and also after the war. Both these officers later went on to head the Pakistan Air Force. -

Who Is Who in Pakistan & Who Is Who in the World Study Material

1 Who is Who in Pakistan Lists of Government Officials (former & current) Governor Generals of Pakistan: Sr. # Name Assumed Office Left Office 1 Muhammad Ali Jinnah 15 August 1947 11 September 1948 (died in office) 2 Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin September 1948 October 1951 3 Sir Ghulam Muhammad October 1951 August 1955 4 Iskander Mirza August 1955 (Acting) March 1956 October 1955 (full-time) First Cabinet of Pakistan: Pakistan came into being on August 14, 1947. Its first Governor General was Muhammad Ali Jinnah and First Prime Minister was Liaqat Ali Khan. Following is the list of the first cabinet of Pakistan. Sr. Name of Minister Ministry 1. Liaqat Ali Khan Prime Minister, Foreign Minister, Defence Minister, Minister for Commonwealth relations 2. Malik Ghulam Muhammad Finance Minister 3. Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar Minister of trade , Industries & Construction 4. *Raja Ghuzanfar Ali Minister for Food, Agriculture, and Health 5. Sardar Abdul Rab Nishtar Transport, Communication Minister 6. Fazal-ul-Rehman Minister Interior, Education, and Information 7. Jogendra Nath Mandal Minister for Law & Labour *Raja Ghuzanfar’s portfolio was changed to Minister of Evacuee and Refugee Rehabilitation and the ministry for food and agriculture was given to Abdul Satar Pirzada • The first Chief Minister of Punjab was Nawab Iftikhar. • The first Chief Minister of NWFP was Abdul Qayum Khan. • The First Chief Minister of Sindh was Muhamad Ayub Khuro. • The First Chief Minister of Balochistan was Ataullah Mengal (1 May 1972), Balochistan acquired the status of the province in 1970. List of Former Prime Ministers of Pakistan 1. Liaquat Ali Khan (1896 – 1951) In Office: 14 August 1947 – 16 October 1951 2. -

The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature

From Upyr’ to Vampir: The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature Dorian Townsend Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Languages and Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of New South Wales May 2011 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Townsend First name: Dorian Other name/s: Aleksandra PhD, Russian Studies Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: School: Languages and Linguistics Faculty: Arts and Social Sciences Title: From Upyr’ to Vampir: The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) The Slavic vampire myth traces back to pre-Orthodox folk belief, serving both as an explanation of death and as the physical embodiment of the tragedies exacted on the community. The symbol’s broad ability to personify tragic events created a versatile system of imagery that transcended its folkloric derivations into the realm of Russian literature, becoming a constant literary device from eighteenth century to post-Soviet fiction. The vampire’s literary usage arose during and after the reign of Catherine the Great and continued into each politically turbulent time that followed. The authors examined in this thesis, Afanasiev, Gogol, Bulgakov, and Lukyanenko, each depicted the issues and internal turmoil experienced in Russia during their respective times. By employing the common mythos of the vampire, the issues suggested within the literature are presented indirectly to the readers giving literary life to pressing societal dilemmas. The purpose of this thesis is to ascertain the vampire’s function within Russian literary societal criticism by first identifying the shifts in imagery in the selected Russian vampiric works, then examining how the shifts relate to the societal changes of the different time periods. -

Postcoloniality, Science Fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Banerjee [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Suparno, "Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3181. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. OTHER TOMORROWS: POSTCOLONIALITY, SCIENCE FICTION AND INDIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English By Suparno Banerjee B. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2000 M. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2002 August 2010 ©Copyright 2010 Suparno Banerjee All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation would not have been possible without the constant support of my professors, peers, friends and family. Both my supervisors, Dr. Pallavi Rastogi and Dr. Carl Freedman, guided the committee proficiently and helped me maintain a steady progress towards completion. Dr. Rastogi provided useful insights into the field of postcolonial studies, while Dr. Freedman shared his invaluable knowledge of science fiction. Without Dr. Robin Roberts I would not have become aware of the immensely powerful tradition of feminist science fiction.