Liaquat Ali Khan: His Life and Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migration and Small Towns in Pakistan

Working Paper Series on Rural-Urban Interactions and Livelihood Strategies WORKING PAPER 15 Migration and small towns in Pakistan Arif Hasan with Mansoor Raza June 2009 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, dealing with urban planning and development issues in general, and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1982 and is a founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in Karachi, whose chairman he has been since its inception in 1989. He is currently on the board of several international journals and research organizations, including the Bangkok-based Asian Coalition for Housing Rights, and is a visiting fellow at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), UK. He is also a member of the India Committee of Honour for the International Network for Traditional Building, Architecture and Urbanism. He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign CBOs, national and international NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies. He has taught at Pakistani and European universities, served on juries of international architectural and development competitions, and is the author of a number of books on development and planning in Asian cities in general and Karachi in particular. He has also received a number of awards for his work, which spans many countries. Address: Hasan & Associates, Architects and Planning Consultants, 37-D, Mohammad Ali Society, Karachi – 75350, Pakistan; e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]. Mansoor Raza is Deputy Director Disaster Management for the Church World Service – Pakistan/Afghanistan. -

Censorship in Pakistani Urdu Textbooks

Censorship in Pakistani Urdu Textbooks S and criticism has always been an active force in Pakistani society. Journalists and creative writers have had to struggle hard to find their way around or across many laws threatening to punish any deviation from the official line on most vital issues. The authorities’ initiative to impose censorship through legislative means dates back to the Public Safety Act Ordinance imposed in October , and later, in , ratified by the first Constituent Assembly of Pakistan as the Safety Act. Apart from numberless political workers, newspapers, and periodicals, the leading literary journals too fell victim to this oppressive piece of legislation which was only the first in a long series of such laws. In fact, Sav®r≥ (Lahore) has the dubious honor of being the first periodical of any kind to be banned, in , under this very Public Safety Act Ordinance. This legal device was also invoked to suspend two other Lahore-based literary periodicals—Nuq∑sh and Adab-e Laπµf—for six months and to incarcerate the editor of Sav®r≥, Zaheer Kashmiri, in without even a trial.1 The infamous Safety Act had well-known literary people on both sides. On the one hand, literary critics such as Mu√ammad ƒasan ‘Askarµ2 found the law perfectly justifiable—indeed, they even praised it. On the other hand, there were writers and editors who were prosecuted under 1See Zamir Niazi, The Press in Chains (Karachi: Karachi Press Club, ), pp. and . 2For details, see Mu√ammad ƒasan ‘Askarµ, Takhlµqµ ‘Amal aur Usl∑b, collected by Mu√ammad Suh®l ‘Umar (Karachi: Nafµs Academy, ) , pp. -

Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates

Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates Syeda Amna Sohail Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates THESIS To obtain the degree of Master of European Studies track Policy and Governance from the University of Twente, the Netherlands by Syeda Amna Sohail s1018566 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Robert Hoppe Referent: Irna van der Molen Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Motivation to do the research . 5 1.2 Political and social relevance of the topic . 7 1.3 Scientific and theoretical relevance of the topic . 9 1.4 Research question . 10 1.5 Hypothesis . 11 1.6 Plan of action . 11 1.7 Research design and methodology . 11 1.8 Thesis outline . 12 2 Theoretical Framework 13 2.1 Introduction . 13 2.2 Jakubowicz, 1998 [51] . 14 2.2.1 Communication values and corresponding media system (minutely al- tered Denis McQuail model [60]) . 14 2.2.2 Different theories of civil society and media transformation projects in Central and Eastern European countries (adapted by Sparks [77]) . 16 2.2.3 Level of autonomy depends upon the combination, the selection proce- dure and the powers of media regulatory authorities (Jakubowicz [51]) . 20 2.3 Cuilenburg and McQuail, 2003 . 21 2.4 Historical description . 23 2.4.1 Phase I: Emerging communication policy (till Second World War for modern western European countries) . 23 2.4.2 Phase II: Public service media policy . 24 2.4.3 Phase III: New communication policy paradigm (1980s/90s - till 2003) 25 2.4.4 PK Communication policy . 27 3 Operationalization (OFCOM: Office of Communication, UK) 30 3.1 Introduction . -

Afghanistan: Political Exiles in Search of a State

Journal of Political Science Volume 18 Number 1 Article 11 November 1990 Afghanistan: Political Exiles In Search Of A State Barnett R. Rubin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Rubin, Barnett R. (1990) "Afghanistan: Political Exiles In Search Of A State," Journal of Political Science: Vol. 18 : No. 1 , Article 11. Available at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops/vol18/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Politics at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Political Science by an authorized editor of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ,t\fghanistan: Political Exiles in Search of a State Barnett R. Ru bin United States Institute of Peace When Afghan exiles in Pakistan convened a shura (coun cil) in Islamabad to choose an interim government on February 10. 1989. they were only the most recent of exiles who have aspired and often managed to Mrule" Afghanistan. The seven parties of the Islamic Union ofM ujahidin of Afghanistan who had convened the shura claimed that. because of their links to the mujahidin fighting inside Afghanistan. the cabinet they named was an Minterim government" rather than a Mgovernment-in exile. ~ but they soon confronted the typical problems of the latter: how to obtain foreign recognition, how to depose the sitting government they did not recognize, and how to replace the existing opposition mechanisms inside and outside the country. Exiles in Afghan History The importance of exiles in the history of Afghanistan derives largely from the difficulty of state formation in its sparsely settled and largely barren territory. -

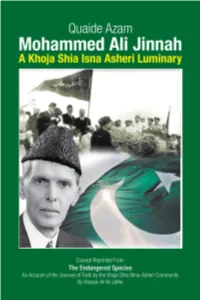

Quide Azam Monograph V3

Quaide Azam Mohammed Ali Jinnah: A Khoja Shia Ithna Asheri Luminary ndia became Independent in 1947 when the country was divided as India and Pakistan. Four men played a significant role in I shaping the end of British rule in India: The British Viceroy, Lord Louis Mountbatten, the Indian National Congress leaders Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, and the Muslim League leader, Mohamed Ali Jinnah. Jinnah led the Muslims of India to create the largest Muslim State in the world then. In 1971 East Pakistan separated to emerge as Bangladesh. Much has been written about the first three in relative complimentary terms. The fourth leading player, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, founding father of Pakistan, lovingly called Quaid-e-Azam (the great leader) has been much maligned by both Indian and British writers. Richard Attenborough's hugely successful film Gandhi has also done much to portray Jinnah in a negative light. Excerpt from Endangered Species | 4 The last British Viceroy, Lord Louis Mountbatten, spared no adjectives in demonizing Jinnah, and his views influenced many writers. Akber S. Ahmed quotes Andrew Roberts from his article in Sunday Times, 18 August,1996: “Mountbatten contributed to the slander against Jinnah, calling him vain, megalomaniacal, an evil genius , a lunatic, psychotic case and a bastard, while publicly claiming he was entirely impartial between Jinnah’s Pakistan and Nehru’s India. Jinnah rose magisterially above Mountbatten’s bias, not even attacking the former Viceroy when, as Governor General of India after partition, Mountbatten tacitly condoned India’s shameful invasion of Kashmir in October 1947.”1 Among recent writers, Stanley Wolport with his biography: Jinnah of Pakistan, and Patrick French in his well researched Freedom or Death analyzing the demise of the British rule in India come out with more balanced portrayal of Jinnah - his role in the struggle for India’s independence and in the creation of Pakistan. -

Opportunities in the Development of Pakistan's Private Sector

Opportunities in the Development of Pakistan’s Private Sector AUTHOR Sadika Hameed 1616 Rhode Island Avenue NW | Washington, DC 20036 t. 202.887.0200 | f. 202.775.3199 | www.csis.org ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Lanham, MD 20706 t. 800.462.6420 | f. 301.429.5749 | www.rowman.com Cover photo: Shutterstock.com. ISBN 978-1-4422-4030-8 Ë|xHSLEOCy240308z v*:+:!:+:! SEPTEMBER 2014 A Report of the CSIS Program on Crisis, Conflict, and Cooperation Blank Opportunities in the Development of Pakistan’s Private Sector AUTHOR Sadika Hameed A Report of the CSIS Program on Crisis, Confl ict, and Cooperation September 2014 ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK About CSIS For over 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has worked to develop solutions to the world’s greatest policy challenges. Today, CSIS scholars are providing strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a nonprofi t or ga ni za tion headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affi liated scholars conduct research and analysis and develop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded at the height of the Cold War by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke, CSIS was dedicated to fi nding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. Since 1962, CSIS has become one of the world’s preeminent international institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global health and economic integration. -

1 KMU AKU SCN 1 1 4001 Alam Zeb Muhammad Iqbal 05-02-92 Swat

POST GRADUATE COLLEGE OF NURSING 1 HAYATABAD PESHAWAR OPEN MERIT LIST FOR BSC NURSING, SESSION 2011(MALE & FEMALE) F R S Basic Qualification (70) . N N N SSC F.Sc Options o o Remarks o Name of Student Father Name D.O.B Domicile Gender . Total Obtained Total Obtained KMU AKU SCN 1 1 4001 Alam Zeb Muhammad Iqbal 05-02-92 Swat 1050 774 1100 639 1 2 3 M 2 2 4002 Ahmad Irshad Fazle Qadeer 03-05-93 Dir lower 1050 847 1100 783 3 1 2 M 3 3 4003 Ishrat Bibi Sher Muhammad Khan 02-01-92 Swat 1050 822 1100 774 1 2 3 F 4 4 4004 Ali Shah Shah Jehan 20-01-92 Swat 1050 804 1100 788 1 2 3 M 5 5 4005 Sami Ullah khan Shafi ullah 15-05-91 Shangla 900 739 1100 825 3 1 2 M 6 6 4006 Rahim Shah Swal Muhammad 20-10-90 Dir lower 1050 636 1100 634 2 1 3 M 7 7 4007 Abdul Lateef Ali Johar 12-09-94 Mardan 1050 542 1100 500 1 2 3 M 8 8 4008 Daud Gohar Gohar ali 25-03-92 Nowshehra 1050 745 1100 589 1 2 3 M 9 9 4009 Ibrahim Sher Zaman khan 04-03-91 Dir lower 1050 648 1100 600 1 2 3 M 10 10 4010 Amjad Hussain Said Amir khan 13-03-93 Dir lower 1050 716 1100 765 1 3 2 M 11 11 4011 Pir Muhammad Khan Muhammad Rashid 19-03-93 Buner 1050 722 1100 672 1 2 3 M 12 12 4012 Ajmal Khan Ajab Khan 02-01-90 Swat 900 675 1100 857 1 3 2 M 13 13 4013 Usman Ghani Sahib Zada 20-03-93 Buner 1050 657 1100 610 1 2 3 M 14 14 4014 Sana Ullah Fazal Wahid 03-04-88 Swat 1050 553 1100 632 1 3 2 M 15 15 4015 Adnan Shah Juma Khan 04-01-94 Shangla 1050 868 1100 834 3 1 2 M 16 16 4016 Rehman Ali Abdur Rehman 26-04-91 Swat 900 533 1100 617 1 3 2 M 17 17 4017 Alam Zeb Jehanzeb 07-02-92 Swat 900 588 1100 -

Jinnah and the Making of Pakistan Week One: Islam As A

Jinnah and The Making of Pakistan Week One: Islam as a Modern Idea Wilfred Cantwell Smith, On Understanding Islam (The Hague: Mouton Publishers, 1981), pp. 41-78. Mohammad Iqbal, The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam, chapters 5 and 6. (http://www.allamaiQbal.com/works/prose/english/reconstruction/index.htm). AltafHusayn Hali, HaWs Musaddas (Delhi: Oxford) Syed Ameer Ali, Carlyle, "The hero as prophet", in On Heraes and Hera- Worship Week Two: The Emergence of Minority Politics Sayyid Ahmad Khan, "Speech of Sir Syed at Lucknow, 1887", in Sir Syed Ahmed on the Present State ofIndian Politics, Consisting ofSpeeches and Letters Reprintedfram the "Pioneer" (AlIahabad: The Pioneer Press, 1888), pp. 1-24. (http://www.columbia.edulitc Imealac Ipritchett IOOislamlinks Itxt sir sayyid luckn ow 1887.html). S. A Khan, "Speech of Sir Syed at Meerut, 1888", in Sir Syed Ahmed on the Present State ofIndian Politics, Consisting ofSpeeches and Letters Reprintedfram the "Pioneer" (AlIahabad: The Pioneer Press, 1888), pp. 29-53. (http://www.columbia.edulitc/mealac/pritchett/OOislamlinks/txt sir sayyid meer ut 1888.html). Lala Lajpat Rai, "Open letters to Sir Syed Ahmad Khan", in Lala Lajpat Rai: Writings and Speeches, Volume One, 1888-1919, ed. byVijaya Chandra Joshi (Delhi: University Publishers, 1966), pp. 1-25. (http://www.col umbia.edu litc/mealac/pritchettl OOislamlinks Itxt lajpatrai 1888 It xt lajpatrai 1888.html). M. A Jinnah, "Presidential address to the Muslim League, Lucknow, 1916" Mohomed AliJinnah: an Ambassador of Unity: His Speeches and Writings, 1912-1917; with a Biographical Appreciation by Sarajini Naidu and a foreword by the Hon 'ble the Rajah ofMahmudabad (Lahore 1918, reprint ed. -

Resultcafexaminationsp2021.Pdf

THE INSTITUTE OF CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS OF PAKISTAN PRESS RELEASE April 29, 2021 Spring 2021 Result of Certificate in Accounting and Finance (CAF) The Council of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Pakistan is pleased to declare the result of the above examination held in March 2021: Candidates Passed-CAF Candidates Passed-CAF CRN Name Credited CRN Name Credited Paper(s) Paper(s) 046836 MUHAMMAD IRFAN ASIF KHOKHAR 078174 HAMZA SALEEM S/o MUHAMMAD ASIF KHOKHAR S/o MUHAMMAD SALEEM KHAN 056117 ALI AHMED ABBASI 078190 SYED IMRAN HAIDER S/o WAKEEL AHMED ABBASI S/o SYED ABID HUSSAIN 063526 UZAIR JAVEED 078759 MUHAMMAD BILAL PATHAN S/o JAVEED SALEEM S/o GHUFRAN AHMED PATHAN 066420 FARAZ NAEEM AHMED 079271 MUHAMMAD UBAID ASHRAF S/o NAEEM AHMED CHAUDHARY S/o RANA MUHAMMAD ASHRAF 068288 USMAN ALI 079584 CH. HAMDI TAHIR S/o PERVAIZ AHMAD S/o CHAUDHRY TAHIR AMIN 068343 FAIZA ASHIQ 079889 MOHSIN KHAN D/o ASHIQ ALI S/o ZULFIQAR ALI KHAN 069546 MUHAMMAD ASAD ULLAH FAROOQ 080002 MAHRUKH ALI S/o MUHAMMAD FAROOQ D/o ZULFQAR ALI 070000 ABUZAR SUBHANI 080328 ANAS TANVEER S/o MUNIR AHMAD S/o TANVEER HUSSAIN 071130 AMIR KHAN 080580 MUHAMMAD ADNAN ARSHAD S/o TILAWAT KHAN S/o MUHAMMAD ARSHAD 071198 FAHAD BIN TARIQ 080632 AHSAN SALMAN S/o TARIQ MEHMOOD S/o MUHAMMAD SALMAN 072264 GHULAM FATIMA 081229 AMMARA ASLAM D/o YAQOOB AHMAD FAROOQI D/o MUHAMMAD ASLAM 072552 IQRA GUL AFSHA 081460 JALAL KHAN D/o GUL SHER KHAN S/o SHAHEEN ULLAH 074194 HAROON KHAN 081473 SARAH ARSHAD S/o ILYAS KHAN D/o ARSHAD SALEEM 074332 SABA IFTIKHAR 082093 MUHAMMAD ARSALAN D/o IFTIKHAR -

4. Leftist Politics in British India, Himayatullah

Leftist Politics in British India: A Case Study of the Muslim Majority Provinces Himayatullah Yaqubi ∗ Abstract The paper is related with the history and political developments of the various organizations and movements that espoused a Marxist, leftist and socialist approach in their policy formulation. The approach is to study the left’s political landscape within the framework of the Muslim majority provinces which comprised Pakistan after 1947. The paper would deal those political groups, parties, organizations and personalities that played significant role in the development of progressive, socialist and non-communal politics during the British rule. Majority of these parties and groups merged together in the post-1947 period to form the National Awami Party (NAP) in July 1957. It is essentially an endeavour to understand the direction of their political orientation in the pre-partition period to better comprehend their position in the post-partition Pakistan. The ranges of the study are much wide in the sense that it covers all the provinces of the present day Pakistan, including former East Pakistan. It would also take up those political figures that were influenced by socialist ideas but, at the same time, worked for the Muslim League to broaden its mass organization. In a nutshell the purpose of the article is to ∗ Research Fellow, National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research, Centre of Excellence, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad 64 Pakistan Journal of History and Culture, Vol.XXXIV, No.I, 2013 study the pre-partition political strategies, line of thinking and ideological orientation of the components which in the post- partition period merged into the NAP in 1957. -

A Stylistic Analysis of Manto's Urdu Short Stories and Their English

A Stylistic Analysis of Manto’s Urdu Short Stories and their English Translations Muhammad Salman Riaz Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Languages, Cultures, and Societies October 2018 - ii - The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his/her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Muhammad Salman Riaz to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2018 The University of Leeds and Muhammad Salman Riaz - iii - Acknowledgements I am thankful to Allah the Merciful for His countless blessings and for making this happen. I am also thankful to my parents for their support and prayers all through my life, and whatever I am today owes much to them. My heartfelt thank goes to my respected supervisor Dr Jeremy Munday for his persistent guidance, invaluable feedback, and patience. He has been a guiding star in every step of my research journey, and I would not have reached my destination without his matchless guidance and selfless help. I would also like to thank Charles Wallace Trust Pakistan whose bursary lessened the financial burden on me, and I was able to concentrate better on my research. I cannot thank my wife Tayyaba Salman enough for standing by me in every thick and thin and motivating me in hours of darkness. -

Sindh and Making of Pakistan

Fatima Riffat * Muhammad Iqbal Chawla** Adnan Tariq*** A History of Sindh from a Regional Perspective: Sindh and Making of Pakistan Abstract Historical literature is full of descriptions concerning the life, thoughts and actions of main Muslim central leadership of India, like the role of Quaid-i-Azam in the creation of Pakistan. However enough literature on the topic, which can be easily accessed, especially in English, has not come to light on the efforts made by the political leadership of smaller provinces comprising today’s Pakistan during the Pakistan Movement. To fill the existing gap in historical literature this paper attempts to throw light on the contribution of Sindh provincial leadership. There are number of factors which have prompted the present author to focus on the province of Sindh and its provincial leadership. Firstly, the province of Sindh enjoys the prominence for being the first amongst all the Muslim-majority provinces of undivided India to have supported the creation of Pakistan. The Sind Provincial Muslim League had passed a resolution on 10 October, 1938, urging the right of political self-government for the two largest religious groups of India, Muslims and Hindus, even before the passage of the Lahore Resolution for Pakistan in 1940. Secondly, the Sindh Legislative Assembly followed suit and passed a resolution in support of Pakistan in March 1943. Thirdly, it was the first Muslim-majority province whose members of the Legislature opted to join Pakistan on 26 June 1947. Fourthly, despite personal jealousies, tribal conflicts, thrust for power, the political leadership in Sindh helped Jinnah to achieve Pakistan.