Lockdown and Shutdowns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015 This document is published by the Center for Diversity and National Harmony with the support of the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund. Publisher : Center for Diversity and National Harmony No. 11, Shweli Street, Kamayut Township, Yangon. Offset : Public ation Date : September 2015 © All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Rakhine State, one of the poorest regions in Myanmar, has been plagued by communal problems since the turn of the 20th century which, coupled with protracted underdevelopment, have kept residents in a state of dire need. This regrettable situation was compounded from 2012 to 2014, when violent communal riots between members of the Muslim and Rakhine communities erupted in various parts of the state. Since the middle of 2012, the Myanmar government, international organisations and non-governmen- tal organisations (NGOs) have been involved in providing humanitarian assistance to internally dis- placed and conflict-affected persons, undertaking development projects and conflict prevention activ- ities. Despite these efforts, tensions between the two communities remain a source of great concern, and many in the international community continue to view the Rakhine issue as the biggest stumbling block in Myanmar’s reform process. The persistence of communal tensions signaled a need to address one of the root causes of conflict: crushing poverty. However, even as various stakeholders have attempted to restore normalcy in the state, they have done so without a comprehensive needs assessment to guide them. In an attempt to fill this gap, the Center for Diversity and National Harmony (CDNH) undertook the task of developing a source of baseline information on Rakhine State, which all stakeholders can draw on when providing humanitarian and development assistance as well as when working on conflict prevention in the state. -

Remaking Rakhine State

REMAKING RAKHINE STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Aerial photograph showing the clearance of a burnt village in northern Rakhine State (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 16/8018/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org INTRODUCTION Six months after the start of a brutal military campaign which forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya women, men and children from their homes and left hundreds of Rohingya villages burned the ground, Myanmar’s authorities are remaking northern Rakhine State in their absence.1 Since October 2017, but in particular since the start of 2018, Myanmar’s authorities have embarked on a major operation to clear burned villages and to build new homes, security force bases and infrastructure in the region. -

“Pre-Election Monitoring Study in Rakhine State”

“Pre-Election Monitoring Study in Rakhine State” Table of Contents KEY FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................................... 2 1. BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 5 1.1. POLITICAL PARTY LANDSCAPE IN RAKHINE STATE............................................................................ 7 1.2. INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS ON FREE AND FAIR ELECTIONS .............................................................. 8 1.3. ELECTORAL SYSTEM IN MYANMAR ................................................................................................. 10 2. OBJECTIVE AND SCOPE OF THE STUDY ..................................................................................... 11 1. METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................ 11 1.1. SAMPLING ...................................................................................................................................... 11 1.2. RESEARCH PROCESS ........................................................................................................................ 12 1.3. LIMITATION OF STUDY .................................................................................................................... 12 2. FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................................ -

UNOSAT Analysis of Destruction and Other Developments in Rakhine State, Myanmar

UNOSAT analysis of destruction and other developments in Rakhine State, Myanmar 7 September 2018 [Geneva, Switzerland] Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Data and Methods ................................................................................................................................... 2 Satellite Images and Processing .......................................................................................................... 2 Satellite Image Analysis ....................................................................................................................... 3 Fire Detection Data ............................................................................................................................. 5 Fire Detection Data Analysis ............................................................................................................... 6 Settlement Locations ........................................................................................................................... 6 Estimation of the destroyed structures .............................................................................................. 6 Results ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 Destruction Visible in Satellite Imagery ............................................................................................. -

Rakhine State, Myanmar

World Food Programme S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 Photographs: ©FAO/F. Del Re/L. Castaldi and ©WFP/K. Swe. This report has been prepared by Monika Tothova and Luigi Castaldi (FAO) and Yvonne Forsen, Marco Principi and Sasha Guyetsky (WFP) under the responsibility of the FAO and WFP secretariats with information from official and other sources. Since conditions may change rapidly, please contact the undersigned for further information if required. Mario Zappacosta Siemon Hollema Senior Economist, EST-GIEWS Senior Programme Policy Officer Trade and Markets Division, FAO Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific, WFP E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org at the following URL address: http://www.fao.org/giews/ The Global Information and Early Warning System on Food and Agriculture (GIEWS) has set up a mailing list to disseminate its reports. To subscribe, submit the Registration Form on the following link: http://newsletters.fao.org/k/Fao/trade_and_markets_english_giews_world S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Rome, 2019 Required citation: FAO. -

Village Tracts of Northern Rakhine State (Buthidaung, Maungdaw, Rathedaung Townships ) N N ' ' 0 0

Myanmar Information Management Unit Village Tracts of northern Rakhine State (Buthidaung, Maungdaw, Rathedaung Townships ) N N ' ' 0 0 3 92°30'E 93°0'E 3 ° ° 1 1 2 2 BANGLADESH Tat Chaung In Tu Lar CHIN STATE Kar Lar Day Hpet Bauk Shu Ye Aung San Hpweit Ya Bway Paletwa Kyaung (! Samee Na Hpay !( Hlaing Thi Kha Maung Seik Ba Da Kar Nan Yar Thit Tone Kaing Nar Gwa Nga Yant Son Mee Taik Chaung (Taungpyoletwea Sub-township) Ta Man Thar Yae Nauk Taungpyoletwea Ngar Thar !( Thet Kaing Kha Maung Pa Da Kyaung Taung Tin May Nyar Chaung Taung Pyo Let Yar Kar Day (Taungpyoletwea War Nar Li Sub-township) Thea Chaung (Taungpyoletwea Pa Da Kar Kun Thee Pin Sub-township) San Kar Ywar Thit (Taungpyoletwea Pin Yin Sub-township) Min Gyi (Tu Lar Wet Kyein Laung Yon Leik Ya Tu Li) Done Paik Kyun Pauk Goke Pi (Taungpyoletwea (Aung Seik Sub-township) Kyun Pauk Sin Oe Pyin) (Taungpyoletwea Kyauk Chaung Sub-township) Kyein Chaung (Taungpyoletwea Myaw Chaung Sub-township) Laung Don Ta Ya Gu Zee Pin Chaung Myauk Ye (a) (Taungpyoletwea Pan Be Chaung Sub-township) Sa Bai Kone Ah Htet Pyu Ma Ka Yin Ma Nyin Tan Pyu Ma Doe Ngar Sar Kyu Kyaung Myo Tan Zee Hton Pyu Ma Ka Taung Nyin Tan Thit Kyet Yoe Pyin Aw Ra Ma (a) Kat Pa Kaung Yae Yee Chaung Nga Khu Ya Ngan Chaung N Pyin Hla N ' Nga Khu Ya Myet Taung Nga Yant ' 0 0 ° U Shey Kya Pwint Hpar Wut Chaung ° 1 Hpyu Chaung Ba Da Nar 1 2 Chan Chaung Thin Ga Net 2 Kyar Gaung (Ywar Thit) Pyin Inn Chaung Taung Myaw Oke Taung Yae Twin Yae Khat Taung Mee Chaung Mee Kyun Chaung Gwa Son Maung Khaung Chaung Zay Ywet Nyoe Dar Gyi Zar -

Atrocity Crimes Against Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State, Myanmar

BEARING WITNESS REPORT NOVEMBER 2017 “THEY TRIED TO KILL US ALL” Atrocity Crimes against Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State, Myanmar SIMON-SKJODT CENTER FOR THE PREVENTION OF GENOCIDE United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Washington, DC www.ushmm.org The United States Holocaust Museum’s work on genocide and related crimes against humanity is conducted by the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide. The Simon-Skjodt Center is dedicated to stimulating timely global action to prevent genocide and to catalyze an international response when it occurs. Our goal is to make the prevention of genocide a core foreign policy priority for leaders around the world through a multipronged program of research, education, and public outreach. We work to equip decision makers, starting with officials in the United States but also extending to other governments and institutions, with the knowledge, tools, and institutional support required to prevent— or, if necessary, halt—genocide and related crimes against humanity. FORTIFY RIGHTS Southeast Asia www.fortifyrights.org Fortify Rights works to ensure and defend human rights for all. We investigate human rights violations, engage policy makers and others, and strengthen initiatives led by human rights defenders, affected communities, and civil society. We believe in the influence of evidence- based research, the power of strategic truth-telling, and the importance of working closely with individuals, communities, and movements pushing for change. We are an independent, nonprofit organization based in Southeast Asia and registered in the United States and Switzerland. The United State Holocaust Memorial Museum uses the name “Burma” and Fortify Rights uses the name “Myanmar” to describe the same country. -

Mimu861v01 120611 3W Rakhine State VT A3.Mxd

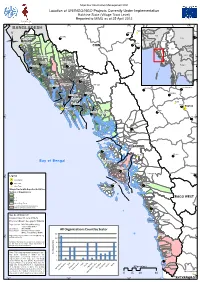

Myanmar Information Management Unit Location of UN/INGO/NGO Projects Currently Under Implementation Rakhine State (Village Tract Level) Reported to MIMU as of 25 April 2012 92°0'E 93°0'E 94°0'E 95°0'E BANGLADESH Pauk Kyaukhtu Mindat (! Bhutan Nepal Pakokku India Paletwa Kachin Maungdaw China Bangladesh Sagaing Taungpyoletwea Kanpetlet Nyaung-U (! CHIN Saw Bagan Vietnam (! Ü Chin Shan (! Mandalay Magway Kayah Laos Buthidaung Rakhine 21°0'N Bago 21°0'N Yangon Kyauktaw Chauk Buthidaung Ayeyarwady Kayin Seikphyu Kyauktaw Thailand Kyaukpadaung Maungdaw Mon Mrauk-U Cambodia Rathedaung MAGWAY Tanintharyi Mrauk-U Salin Ponnagyun Rathedaung Minbya Sidoktaya Yenangyaung Minbya Pwintbyu Ponnagyun Pauktaw Saku (! Sittwe Pauktaw Minbu Magway .! Sittwe .! Ngape Myebon Myebon Minhla 20°0'N Ann 20°0'N Ann RAKHINE Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Mindon (! Bay of Bengal Kyaukpyu Ramree Ramree Toungup Kamma Legend 19°0'N 19°0'N .! State Capital Main Town Munaung Toungup (! Other Town Village Tracts with Reported Activities Munaung Number of Organizations 1 2 - 3 BAGO WEST 4 - 6 Other Village Tracts Township (Orgainzations presence Thandwe without specifying Village Tract) Map ID: MIMU861v01 Creation Date: 11 June 2012.A3 Thandwe Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 Data Sources : Who/What/Where data collected by MIMU Boundaries : WFP/MIMU Place Name : Ministry of Home Affairs All Organizations Count by Sector (GAD), translated by MIMU 12 Kyeintali Map produced by the MIMU - [email protected] (! www.themimu.info 18°0'N 10 18°0'N Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used 8 on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Situation of Human Rights of Rohingya Muslims and Other Minorities in Myanmar

A/HRC/45/5 Advance Edited Version Distr.: General 3 September 2020 Original: English Human Rights Council Forty-fifth session 14 September–2 October 2020 Agenda item 2 Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General Situation of human rights of Rohingya Muslims and other minorities in Myanmar Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights* Summary The present report is submitted pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 42/3, in which the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) is requested to submit to the Council at its forty-fifth session a report on the implementation of the recommendations of the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar, including those on accountability, and on progress in the situation of human rights in Myanmar, including of Rohingya Muslims and other minorities. * The present report was submitted after the deadline so as to include the most recent information. A/HRC/45/5 I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 42/3, in which the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights was requested to follow up on the implementation by the Government of Myanmar of the recommendations made by the independent international fact-finding mission, including those on accountability, and to continue to track progress in relation to human rights in Myanmar, including of Rohingya Muslims and other minorities. 2. The report was prepared on the basis of primary and secondary information collected from various sources – including primary witness testimonies, the Government, the United Nations, civil society organizations, representatives of ethnic and religious minority communities, diplomats, media professionals, academics and other experts. -

Draft Restricted

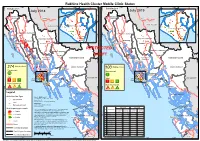

Rakhine Health Cluster Mobile Clinic Status N N N N ' ' ' ' 0 0 92°30'E 93°0'E 93°30'E 0 92°30'E 93°0'E 93°30'E 0 3 3 3 3 ° ° ° ° 1 1 Bangladesh 1 Bangladesh 1 2 2 July 2018 2 July 2019 2 MAUNGDAW MAUNGDAW TOWNSHIP Paletwa TOWNSHIP Paletwa CHIN STATE CHIN STATE SITTWE TOWNSHIP SITTWE TOWNSHIP BUTHIDAUNG TOWNSHIP N N N N ' ' ' BUTHIDAUNG TOWNSHIP ' 0 0 0 0 ° ° ° ° 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 KYAUKTAW TOWNSHIP KYAUKTAW TOWNSHIP Buthidaung Sittwe Buthidaung Sittwe Maungdaw Kyauktaw Maungdaw Kyauktaw RESTRICTED MRAUK-U TOWNSHIP MRAUK-U TOWNSHIP Mrauk-U DRAFT Mrauk-U RATHEDAUNG RATHEDAUNG PONNAGYUN PONNAGYUN TOWNSHIP RAKHINE STATE TOWNSHIP RAKHINE STATE N TOWNSHIP N N TOWNSHIP N ' ' ' ' 0 0 0 0 3 Rathedaung 3 3 Rathedaung 3 ° ° ° ° 0 0 0 0 2 2 2 2 Mobile clinics MINBYA TOWNSHIP Mobile clinics MINBYA TOWNSHIP Minbya 274 Ponnagyun Minbya 100 Ponnagyun Government Government 116 PAUKTAW PAUKTAW TOWNSHIP 1 TOWNSHIP Joint ANN TOWNSHIP SITTWE Joint SITTWE ANN TOWNSHIP Pauktaw Pauktaw TOWNSHIP TOWNSHIP 7 6 4 Sittwe Sittwe 1 4 5 Non Government Non Government N N N N ' Myebon ' ' Myebon ' 0 0 0 0 ° ° ° ° 0 81 39 12 0 0 0 2 2 2 54 21 8 2 Legend MYEBON TOWNSHIP MYEBON TOWNSHIP Clinic Provider Type Map ID: MIMU1546v04 Creation Date: 17 September 2019 Government Paper Size: A3 Joint Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 Data Source: Non-Government Health Cluster (Rakhine State) Base map: MIMU Visit frequency per month July 2018 July 2019 Clinics not displayed in the maps because of missing geographic No Township Mobile Vistits/ Mobile Vistits/ < 4 visits coordinates: 9 locations in 2018 and 6 locations in 2019 N N N Clinics Month Clinics Month N ' Place Names: General Administration Department (GAD) and field ' ' ' 0 0 0 0 3 sources.Place names on this product are in line with the general 3 3 3 ° ° ° 1 Sittwe 92 404 56 328 ° 9 4 - 8 visits cartographic practice to reflect the names of such places as 9 9 9 1 KYAUKPYU TOWNSHIP 1 1 2 Buthidaung 64 85 6 8 KYAUKPYU TOWNSHIP 1 designated by the government concerned. -

Tsp Map VL Buthidaung

Myanmar Information Management Unit Buthidaung Township - Rakhine State 92°15'E 92°20'E 92°25'E 92°30'E 92°35'E 92°40'E 92°45'E 92°50'E 92°55'E BHUTAN 21°25'N INDIA CHINA BANGLADESH Ü VIETNAM LAOS 21°20'N THAILAND CAMBODIA 21°20'N Paletwa PALETWA Sin Shey Myo (198132) (Ba Da Kar) Ah Htet Bo Ka Lay (198127) (Ba Da Kar) 21°15'N Auk Bo Ka Lay (198128) (Ba Da Kar) Kyee Hnoke Thee (198129) (Ba Da Kar) Kyaung Zar Hpyu (198126) (Ba Da Kar) Pan Zi (198125) (Ba Da Kar) 21°15'N Nga/Myin Baw Kha Mway (198131) Taungpyoletwea (Ba Da Kar) Nga/Myin Baw Ku Lar (198130) (Ba Da Kar) Ba Da Kar (198124) (Ba Da Kar) Tha Ra Zaing (198281) (Aye Yar Cha) Pu Zun Chaung (198134) Ah Yaing Kwet Chay (198263) (Kyaung Taung) (Laung Yon) 21°10'N Sar Kaing (198135) Laung Chaung (198249) (Kyaung Taung) Pe Tha Du (West) (198152) (Kha Maung Chaung) (Kyun Pauk) Thea Ni Chaung (198136) Kyaw U (198137) (Kyaung Taung) (Kyaung Taung) Tin May (198139) (Tin May) Kyauk Twe Chaung (198138) Kyaung Taung (198133) (Kyaung Taung) (Kyaung Taung) Kyauk See (198147) 21°10'N (Kyun Pauk) BUTHIDAUNG MAUNGDAW Pe Tha Htu (198143) Nan Tha Yway (198247) (Goke Pi) (Kha Maung Chaung) Kyway Chaung Kha Mway (198151) Pe Lun Kha Mway (198150) (Kyun Pauk) (Kyun Pauk) Oe Hpyu (Thet + Myo) (198145) Pauk Kyat Wa (198209) Kyway Chaung Kha Mway (Lower) (198153) (Goke Pi) (Ta Ya Gu) (Kyun Pauk) Oh Byu (198142) Sa Hone Kha Mway (198144) Kyway Chaung Rakhine (198149) (Goke Pi) (Goke Pi) Sin Ma U Kaing (198205) (Kyun Pauk) (Ta Ya Gu) Hmaing Sa Ri (198198) Kyway Chaung Ku Lar (198148) Kyun Pauk Ku Lar (198146) -

A Background to the Security Crisis in Northern Rakhine

ISSUE: 2017 No. 79 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore | 23 October 2017 A Background to the Security Crisis in Northern Rakhine Ye Htut* EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • On 25 August 2017, the day after Kofi Annan’s Rakhine Advisory Commission submitted its report, the Rohingya group ARSA simultaneously attacked 30 police outposts and one army regiment’s headquarters. The Myanmar Army responded with a massive security operation that led to more than 500,000 Rohingya people fleeing to Bangladesh. • Rakhine State has had a history of Muslim separatist movements since 1948, and successive governments have tried to control illegal immigration and prevent separatist movements in Northern Rakhine State. In 2004, the removal of military intelligence chief General Khin Nyunt weakened the Myanmar government’s intelligence network in Rakhine State, and in 2013, the security situation worsened when the Border and Immigration Control Command was disbanded. • Without these two security apparatuses, the government lacked intelligence on separatist sentiments and illegal operations in Northern Rakhine State, and security forces were caught off-guard by the ARSA attacks in October 2016 and August 2017. • The current humanitarian crisis, the breakdown of law and order, and the communal violence and hatred in Northern Rakhine State are not only a legacy of the past but also contemporary developments that are seeing the emergence of a new terrorist group with extremist links. * Ye Htut is Visiting Senior Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute and former Information Minister of Myanmar. 1 ISSUE: 2017 No. 79 ISSN 2335-6677 BACKGROUND1 Concurrent with Burma’s independence negotiations with the the United Kingdom, Muslims in the Buthidaung-Maungdaw area of Northern Arakan2 in Burma had appealed to what was then East Pakistan (today’s Bangladesh) to annex these areas.