JTS and the Conservative Movenlent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Debate Over Mixed Seating in the American Synagogue

Jack Wertheimer (ed.) The American Synagogue: A Sanctuary Transformed. New York: Cambridge 13 University Press, 1987 The Debate over Mixed Seating in the American Synagogue JONATHAN D. SARNA "Pues have never yet found an historian," John M. Neale com plained, when he undertook to survey the subject of church seating for the Cambridge Camden Society in 1842. 1 To a large extent, the same situation prevails today in connection with "pues" in the American syn agogue. Although it is common knowledge that American synagogue seating patterns have changed greatly over time - sometimes following acrimonious, even violent disputes - the subject as a whole remains unstudied, seemingly too arcane for historians to bother with. 2 Seating patterns, however, actually reflect down-to-earth social realities, and are richly deserving of study. Behind wearisome debates over how sanctuary seats should be arranged and allocated lie fundamental disagreements over the kinds of social and religious values that the synagogue should project and the relationship between the synagogue and the larger society that surrounds it. As we shall see, where people sit reveals much about what they believe. The necessarily limited study of seating patterns that follows focuses only on the most important and controversial seating innovation in the American synagogue: mixed (family) seating. Other innovations - seats that no longer face east, 3 pulpits moved from center to front, 4 free (un assigned) seating, closed-off pew ends, and the like - require separate treatment. As we shall see, mixed seating is a ramified and multifaceted issue that clearly reflects the impact of American values on synagogue life, for it pits family unity, sexual equality, and modernity against the accepted Jewish legal (halachic) practice of sexual separatiop in prayer. -

'Jhe Umertcan 'Jitle Ussocia.Tion, 2 TITLE NEWS

• SEPTEMBER, 1926 CONTENTS THE MONTHLY LETTER ______________________________________ Page 2 EDITOR'S PAGE ------------------------------------------------------ " 3 "LIABILITY OF ABSTRACTERS" By V. E. Phillips ___________________________________________ --------- ------- ___ " 4 An interesting presentation of this subject, and something that will be very valuable to have. REPORTS OF STATE MEETINGS Oregon ---------------------- -------------------- --- -- ----- --------· " 10 Wisconsin ---------------·------------·----------------------------- " 10 Montana ------------------------------------------------------------ " 11 South Dakota ----------·----------------------------------------- " 11 North Dakota -------------------------------------- _____________ " 12 Ohio ----------·----------------------------------------------------· " 13 LAW QUESTIONS AND THE C 0 U R T S ANSWERS ·----------· ·-------------- ------------- ---------------- " 14 The Monthly Review. SUSTAINING FUND MEMBERSHIP ROLL- 1926 -------·---------------------- ---- ------ --- ---- --------------- ---- " 17 ABSTRACTS OF LAND TITLES ---· ----------------- ------ - " 20 Another installment on their preparation. MISCELLANEOUS INDEX ------------------------------------ " 22 News of the title world. ANNOUNCEMENTS OF STATE MEETINGS Kansas Title Association ------------------------------- " 21 Michigan Title Association ------------------------------ " 21 Nebraska Ttitle Association -------------------·-·-·-·-· " 24 A PUBLICATION ISSUED MONTHLY BY 'Jhe Umertcan 'Jitle Ussocia.tion, -

Volume 124, Issue 6 (The Sentinel, 1911

-- jr .1 V £L Aovemoer 6, 1941 .111 ,. Ili. 4A In an impressive double ceremony, two sis- In honor of the betrothal of Miss Marian ters were united in matrimony, Nettie and Loeffler, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. M. Loeffler Josephine Silver, daughters of Mr. and Mrs. to Mr. Henry Pollak, son of Mr. and Mrs. Emil H. W. Silver of 3520 Lake Shore Drive, were Pollak, a dinner party was tendered the young married at the Belmont Hotel on Sunday, Octo- couple by Mrs. Emil Pollak, in which members R. AND MRS. Leo Goldstein of 1540 ber 26. Miss Nettie Silver was wed to Mr. of both families joined in the celebration. Lake Shore Drive left last week for Clyde Korman, son of Mr. and Mrs. Korman Among those present on this special occasion New York City. Mr. Goldstein has al- of the Melrose Hotel, and Josephine to Mr. were Mr. and Mrs. Oscar Berlin, Mrs. Birdie Goldstein is ready returned to this city. Mrs. Barney Joseph of the Parkway Hotel. Rabbi Levy, Mrs. Joseph Reich, Mr. and Mrs. Rudolph remaining in New York for another week. Solomon Goldman officiated. Following the Sabbath, Mr. and Mrs. Harry Glickauf, Mr. Mr. and Mrs. Egmont H. Frankel of Toronto, double nuptials, a breakfast was served at the and Mrs. L. Hecht, Mr. and Mrs. M. Loeffler, Canada, who were the guests of their mother, Belmont Hotel, and the two couples left on a Mr. and Mrs. Al Horn, Mr. Jerome Sabbath, Mrs. Abraham Hartman of the Chicago Beach double honeymoon. On Sunday, November 2, Mr. -

Fifty Third Year the Jewish Publication Society Of

REPORT OF THE FIFTY THIRD YEAR OF THE JEWISH PUBLICATION SOCIETY OF AMERICA 1940 THE JEWISH PUBLICATION SOCIETY OF AMERICA OFFICERS PRESIDENT J. SOLIS-COHEN, Jr., Philadelphia VICE-PRESIDENT HON. HORACE STERN, Philadelphia TREASURER HOWARD A. WOLF, Philadelphia SECRETARY-EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR MAURICE JACOBS, Philadelphia EDITOR DR. SOLOMON GRAYZEL, Philadelphia HONORARY VICE-PRESIDENTS ISAAC W. BERNHEIM3 Denver SAMUEL BRONFMAN* Montreal REV. DR. HENRY COHEN1 Galveston HON. ABRAM I. ELKUS3 New York City Louis E. KIRSTEIN1 Boston HON. JULIAN W. MACK1 New York City JAMES MARSHALL2 New York City HENRY MONSKY2 Omaha HON. MURRAY SEASONGOOD3 Cincinnati HON. M. C. SLOSS3 San Francisco HENRIETTA SZOLD2 Jerusalem TRUSTEES MARCUS AARON3 Pittsburgh PHILIP AMRAM3 Philadelphia EDWARD BAKER" Cleveland FRED M. BUTZEL2 Detroit J. SOLIS-COHEN, JR.3 Philadelphia BERNARD L. FRANKEL2 Philadelphia LIONEL FRIEDMANN3 Philadelphia REV. DR. SOLOMON GOLDMAN3 Chicago REV. DR. NATHAN KRASS1 New York City SAMUEL C. LAMPORT1 New York City HON. LOUIS E. LEVINTHALJ Philadelphia HOWARD S. LEVY1 Philadelphia WILLIAM S. LOUCHHEIM3 Philadelphia 1 Term expires in 1941. 2 Term expires in 1942. 3 Term expires in 1943. 765 766 AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK REV. DR. LOUIS L. MANN' Chicago SIMON MILLER2 Philadelphia EDWARD A. NORMAN3 New York City CARL H. PFORZHEIMER1 New York City DR. A. S. W. ROSENBACH1 Philadelphia FRANK J. RUBENSTEIN2 Baltimore HARRY SCHERMAN1 New York City REV. DR. ABBA HILLEL SILVERJ Cleveland HON. HORACE STERN2 Philadelphia EDWIN WOLF, 2ND* Philadelphia HOWARD A. WOLF* Philadelphia PUBLICATION COMMITTEE HON. LOUIS E. LEVINTHAL, Chairman Philadelphia REV. DR. BERNARD J. BAMBERGER Albany REV. DR. MORTIMER J. COHEN Philadelphia J. SOLIS-COHEN, JR Philadelphia DR. -

A Journal of Jewish Responsibility Control Us

we dare not tolerate conditions which brutalize and Sh'ma dehumanize. But humanness means the power to control conditions rather than letting conditions a journal of Jewish responsibility control us. Humanness demands individual responsibility 1/20, NOVEMBER 19,1971 The truth of the matter is that millions upon mil- lions of men, women, and children of all races and creeds have suffered privation, prejudice, pogroms, and poverty. There are countless people who faced the same conditions that were the lot of those who are convicted criminals. These include millions of black people. They did not end up as felons and ac- cused murderers—but as productive, law-abiding members of our society. The difference between those who allow conditions to make them criminals and those who are able to overcome the conditions under which they live must lie—at least in part—in Thoughts about thoughts about attica-1 the inner assumption of responsibility. The lack of such sense leads to criminality and self-destruction. Seymour Siegel The thrust of the argument of many who write and speak on the matter is that if the conditions are bad The prisons and the prisoners of our country have enough, then what happens, however heinous, is to suddenly become one of the prime challenges to our be attributed to the deficiencies of our society consciences. Some have known for a long time that rather than to deficiencies of will and character, lt our correctional institutions have not corrected and seems to me that this attitude represents the ulti- that our prisons were schools for crime. -

124900176.Pdf

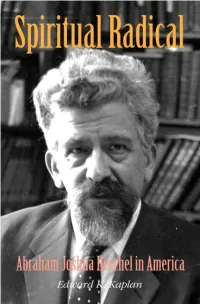

Spiritual Radical EDWARD K. KAPLAN Yale University Press / New Haven & London [To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Spiritual Radical Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund. Copyright © 2007 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Bodoni type by Binghamton Valley Composition. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kaplan, Edward K., 1942– Spiritual radical : Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 / Edward K. Kaplan.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-11540-6 (alk. paper) 1. Heschel, Abraham Joshua, 1907–1972. 2. Rabbis—United States—Biography. 3. Jewish scholars—United States—Biography. I. Title. BM755.H34K375 2007 296.3'092—dc22 [B] 2007002775 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10987654321 To my wife, Janna Contents Introduction ix Part One • Cincinnati: The War Years 1 1 First Year in America (1940–1941) 4 2 Hebrew Union College -

ABOUT THIS BOOK Jewish Life in Cleveland in the 1920S and 1930S

ABOUT THIS BOOK Jewish Life in Cleveland in the 1920s and 1930s by Leon Wiesenfeld This book, published in 1965, is best understood by its subtitle: “Memoirs of a Jewish Journalist”. It is not a history, but rather Leon Wiesenfeld’s accounts of some events, written from his perspective, which appeared in his Jewish Voice Pictorial. Wiesenfeld was more than a journalist. He championed the Jewish people and fought their enemies. He worked for an inclusive Jewish community, with cooperation between the “assimilated Jews” and the Yiddish-speaking Jews he wrote for who in the 1930s were the majority of Cleveland’s Jews. He was a passionate Zionist and a supporter of Rabbi Abba Hillel Silver. Wiesenfeld (Feb. 2, 1885 – March 1, 1971) was born in Rzeszow, Poland and worked for Polish and German publications before coming to America. He worked briefly in New York for Abraham Cahan's Jewish Daily Forward before coming to Cleveland in 1924. For 10 years he was the associate editor of the Yiddishe Velt (Jewish World), Cleveland's principal Yiddish-language newspaper, before becoming its editor in 1934. In 1938 he left to establish an English-Yiddish weekly Die Yiddishe Stimme (Jewish Voice) which failed after about a year. He then started an English language annual, Jewish Voice Pictorial, which endured into the 1950s. (From the entry in the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.) The book’s introduction was written by Moses Zvi Frank, a long-time Jewish journalist. Frank’s review of the book in the Indiana Jewish Post of May 7, 1965 notes that he translated it from chapters Wiesenfeld had written in Yiddish. -

Personal Material

1 MS 377 A3059 Papers of William Frankel Personal material Papers, correspondence and memorabilia 1/1/1 A photocopy of a handwritten copy of the Sinaist, 1929; 1929-2004 Some correspondence between Terence Prittie and Isaiah Berlin; JPR newsletters and papers regarding a celebration dinner in honour of Frankel; Correspondence; Frankel’s ID card from a conference; A printed article by Frankel 1/1/2 A letter from Frankel’s mother; 1936-64 Frankel’s initial correspondence with the American Jewish Committee; Correspondence from Neville Laski; Some papers in Hebrew; Papers concerning B’nai B’rith and Professor Sir Percy Winfield; Frankel’s BA Law degree certificate 1/1/3 Photographs; 1937-2002 Postcards from Vienna to I.Frankel, 1937; A newspaper cutting about Frankel’s meeting with Einstein, 2000; A booklet about resettlement in California; Notes of conversations between Frankel and Golda Meir, Abba Eban and Dr. Adenauer; Correspondence about Frankel’s letter to The Times on Shylock; An article on Petticoat lane and about London’s East End; Notes from a speech on the Jewish Chronicle’s 120th anniversary dinner; Notes for speech on Israel’s prime ministers; Papers concerning post-WW2 Jewish education 1/1/4 JPR newsletters; 1938-2006 Notes on Harold Wilson and 1974 General Election; Notes on and correspondence with Oswald Mosley, 1966 Correspondence including with Isaiah Berlin, Joseph Leftwich, Dr Louis Rabinowitz, Raphael Lowe, Wolfe Kelman, A.Krausz, Norman Cohen and Dr. E.Golombok 1/1/5 Printed and published articles by Frankel; 1939, 1959-92 Typescripts, some annotated, for talks and regarding travels; Correspondence including with Lord Boothby; MS 377 2 A3059 Records of conversations with Dr. -

Aaron Leonard Mackler

AARON LEONARD MACKLER Department of Theology (412) 396-5985 Duquesne University [email protected] Pittsburgh, PA 15282 Education Georgetown University, Washington, DC 1986-92 Ph.D., Philosophy, 1992 Dissertation Title: “Cases and Judgments in Ethical Reasoning: An Appraisal of Contemporary Casuistry and Holistic Model for the Mutual Support of Norms and Case Judgments” Dissertation Committee: Tom L. Beauchamp (mentor), Henry Richardson, LeRoy Walters Jewish Theological Seminary of America, New York, NY 1980-85 M.A., Rabbinic ordination, 1985 Yale University, New Haven, CT 1976-80 B.A., summa cum laude, Religious Studies and Biochemistry, 1980 Experience Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA 1994-present ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR 2000-present, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR 1994-2000: Teach undergraduate and graduate courses, including “Health Care Ethics,” “Human Morality,” “Judaism,” “Interpersonal Ethics,” “Bioethics,” “Justice and the Ethics of Health Care Delivery,” and “Jewish Health Care Ethics, ”; serve as director and reader for doctoral dissertations and examiner for comprehensive examinations; served as Director of the Health Care Ethics Center, 2006-08. Jewish Theological Seminary, New York, NY 1992-94 VISITING ASSISTANT PROFESSOR: Taught “Jewish Philosophical Texts,” “Jewish Approaches to Biomedical Ethics,” and “Readings in Philosophical Ethics,” to undergraduate and graduate students. New York State Task Force on Life and the Law, New York, NY 1990-94 STAFF ETHICIST: Examined and researched issues in biomedical ethics; participated in writing reports that analyze ethical and social issues and present legislative proposals on such issues as health care decision making (When Others Must Choose), assisted suicide (When Death is Sought), and reproductive and genetic technologies; spoke to public and professional groups on bioethical concerns. -

Zionist Odd Couple

Look to thc Fock ,.eom attl,ich l.t t uteee he.un E lJrri, 1tJ-5t tgrtrt cbtcoco Jeal)lsl') brstonrcol soctetJ Vol.2l,No. 8, winter, 1997 ,{{'j,,, : ,:'r i,, ; iu" :i.;, :!', 'iffl;1!i" # ffiffiffiffi Prof.Paula Zionist Odd Couple: Pfefferto WhenChaim WeizmanPersuaded Albert DeliverFirst Einstein to Join Him in a Lecture Tour that Brought the TwoMen to Chicago,He Set OrlinskyTalk in Motion One of the More Unlikely PaulaPfeffer, associate professor Pairings in Zionist ActiviQ History of histon at Loyola Universityof By Walter Roth Chicago,rvill deliver the first rn a seriesof annuallectures honoring the hicagosaw many of Europe'smost prominent Zronists pass through long-time Board memoryof Society in theearly decades of tlrecentury, but it is possiblethe most unusual member and rvell-knolm Chrcago oarrof all wasAlbert Einstein and Chaim Weizman. When Aaron activistElsie Orlinsky. Aaronsohn,Shmariyahu Levin, Vladimir Jabotinsky,and Weizmanhimself Pfeffer'stalk is titled,"A Homefor cameto Chicago,each was a seasonedZionist speakerand public figure Evelr'Baby. a Babyfor EveryHome: a politicalpositions Jewishadoption in Chicago." whose would havebeen farniliar to mostin their audiences. Pfeffcr will Einstein, in contrast, was a Zionist unknown. The most onpaEe 3) famousscientist in the world, he was onlyjust beginning onpase t) speak at Lovola Goktinued Gontinued Rabbi Alex J. Goldmanhas won the 1996 Alex Goldman Doris Minsky Memorial Award. His Inside: mutsscript, My Father, Myself A Son'sMem- roral HistoryExcerpt of NamedSixth oir ofhis -

Directories Lists Necrology National Jewish Organizations1

Directories Lists Necrology National Jewish Organizations1 UNITED STATES Organizations are listed according to functions as follows: Religious, Educational 305 Cultural 299 Community Relations 295 Overseas Aid 302 Social Welfare 323 Social, Mutual Benefit 321 Zionist and Pro-Israel 326 Note also cross-references under these headings: Professional Associations 334 Women's Organizations 334 Youth and Student Organizations 335 COMMUNITY RELATIONS Gutman. Applies Jewish values of justice and humanity to the Arab-Israel conflict in AMERICAN COUNCIL FOR JUDAISM (1943). the Middle East; rejects nationality attach- 307 Fifth Ave., Suite 1006, N.Y.C., 10016. ment of Jews, particularly American Jews, (212)889-1313. Pres. Clarence L. Cole- to the State of Israel as self-segregating, man, Jr.; Sec. Alan V. Stone. Seeks to ad- inconsistent with American constitutional vance the universal principles of a Judaism concepts of individual citizenship and sep- free of nationalism, and the national, civic, aration of church and state, and as being a cultural, and social integration into Ameri- principal obstacle to Middle East peace, can institutions of Americans of Jewish Report. faith. Issues of the American Council for Judaism; Special Interest Report AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE (1906). In- stitute of Human Relations, 165 E. 56 St., AMERICAN JEWISH ALTERNATIVES TO N.Y.C., 10022. (212)751-4000. Pres. May- ZIONISM, INC. (1968). 133 E. 73 St., nard I. Wishner; Exec. V. Pres. Bertram H. N.Y.C., 10021. (212)628-2727. Pres. Gold. Seeks to prevent infraction of civil Elmer Berger; V. Pres. Mrs. Arthur and religious rights of Jews in any part of 'The information in this directory is based on replies to questionnaires circulated by the editors. -

(I) the Five Jewish Influences on Ramah

THE JACOB RADER MARCUS CENTER OF THE AMERICAN JEWISH ARCHIVES MS-831: Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Foundation Records, 1980–2008. Series C: Council for Initiatives in Jewish Education (CIJE). 1988–2003. Subseries 5: Communication, Publications, and Research Papers, 1991–2003. Box Folder 42 2 Fox, Seymour, and William Novak. Vision at the Heart. Planning and drafts, February 1996-May 1996. For more information on this collection, please see the finding aid on the American Jewish Archives website. 3101 Clifton Ave, Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 513.487.3000 AmericanJewishArchives.org FROM: "Dan Pekarsky", INTERNET:[email protected] TO: Nessa Rapoport, 74671,3370 Nessa Rapoport, 74671,3370 DATE: 2/5/96 10:19 AM Re: Ramah and my paper Sender: [email protected] Received: from audumla.students.wisc.edu (students.wisc.edu [144.92.104.66]) by dub-img-4.compuserve.com (8.6.10/5.950515) id JAA22229; Mon, 5 Feb 1996 09:56:41 -0500 Received: from mail.soemadison.wisc.edu by audumla.students.wisc.edu; id IAA111626 ; 8.6.9W/42; Mon, 5 Feb 1996 08:56:40 -0600 From: "Dan Pekarsky" <[email protected]> Reply-To: [email protected] To: [email protected], [email protected] Date: Sun, 04 Feb 1996 21 :12:00 -600 Subject: Ramah and my paper X-Gateway: iGate, (WP Office) vers 4.04m - 1032 MIME-Version: 1.0 Message-Id: <[email protected]> Content-Type: TEXT/PLAIN; Charset=US-ASCII Content-Transfer-Encoding: ?BIT Nessa, I am finding the in-progress Ramah piece very interesting, and I'm struck by the number of times my own intuitive reactions are mirrored a few lines down by your own comments in the brackets.