PDF (Thesis Document)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outdoor Club Japan (OCJ) 国際 アウトドア・クラブ・ジャパン Events

Outdoor Club Japan (OCJ) 国際 アウトドア・クラブ・ジャパン Events Norikuradake Super Downhill 10 March Friday to 12 March Monday If you are not satisfied ski & snowboard in ski area. You can skiing from summit. Norikuradake(3026m)is one of hundred best mountain in Japan. This time is good condition of backcountry ski season. Go up to the summit of Norikuradake by walk from the top of last lift(2000m). Climb about 5 hours and down to bottom lift(1500m) about 50 min. (Deta of last time) Transport: Train from Shinjuku to Matsumoto and Taxi from Matsumoto to Norikura-kogen. Return : Bus from Norikura-kogen to Sinshimashima and train to Shinjuku. Meeting Time & Place : 19:30 Shijuku st. platform 5 car no.1 for super Azusa15 Cost : About Yen30000 Train Shinjuku to matsumoto Yen6200(ow) but should buy 4coupon ticket each coupon Yen4190 or You can buy discount ticket shop in town price is similar. (price is non-reserve seat) Taxi about Yen13000 we will share. Return bus Yen1300 and local train Yen680. Inn Yen14000+tax 2 overnight 2 breakfast 1 dinner (no dinner Friday) Japanese room and hot spring! Necessary equipment : Skiers & Telemarkers need a nylon mohair skin. Snowboarders need snowshoes. Crampons(over 8point!) Clothes: Gore-tex jacket and pants, fleece, hut, musk, gloves, sunglasses, headlamp, thermos, lunch, sunscreen If you do not go up to the summit, you can enjoy the ski area and hot springs. 1 day lift pass Yen4000 Limit : 12persons (priority is downhill from summit) In Japanese : 026m)の頂上からの滑降です。 ゲレンデスキーに物足りないスキーヤー、スノーボーダー向き。 山スキーにいいシーズンですが、天気次第なので一応土、日と2日間の時間をとりました。 -

UMVP Joyous Ibanriypatpr Mpraui Red China Rejects I JN Cease Fire Plea

\ THURSDAY. DECEMBER t t , I960 Averigo Daily Net Praaa Ron Tha Weather iVmurlfPster ^ornittg l|rralb For IIm Week Ending rsfewiM at C. a. We Dsermber 16, 198# TaOiy wtntor Xtac David U)dfa. No. tl. I. O. 10,177 cleedlweeei highest I o. wiu opan Its mMtinc at lav- nnto t t i tenight, Bght About Town on o'eiodc tomorrow ntiht bccauM ir o f the A m m iBanriypatpr MpraUi snnw sr m at tow i o f tha Chrlatmaa party which will I nf Clieeletleee etoedy aad eel Okitotanu foOdw. WRAP YOURSELF jUmicfcestor— 4 City of VIttago Chmrm Om OOd raOowa and lu ll b « h tH tomorrow at A. briaf meaUng of Manchaatar • t tlw Odd ftUowa ban. Juvanlla Orange will ba held to IN THIS BEAUTIFUL V O I^LX X , NO. 70 ICTaasMsd AdvtoUalag ea Pngs 16) MANCHESTER, CONN^ FRIDAY, DECEMBER 22, 1950 (SIXTEEN PAGES) morrow evening at 6:30 In Tinker ^ joyous PRICE FOUR CENTS 'a Harald erronooualy UMVP tba party for tonlcbt. halL and will be followed by movleo. A t laat nlghfa meeting of Man- chaaUr Orange In Orange hall Mlaa i t r aai Mn. rtank J. Uaichaae I# td'OaWaad atfoat wlU i5aod tto Edith Winiama of Tolland Turn pike, waa elected matron of tha QUILTED \ and and catrUtmas with tala- Ntf^hillawTortt. Jpvenila Orange._________________ ROBE Red China Rejects I J. N. Cease Fire Plea Smartly atylad in wrap around or coachman mod els of soft rayon satin. Santa Geta Something Court Delays Report from Brussels West Agrees Assorted cotors. -

I Cyle. Turbine Generators and Coaxial Geared Electric Machines Applied for Paddled Vehicles and Apparatus

I CYLE. TURBINE GENERATORS AND COAXIAL GEARED ELECTRIC MACHINES APPLIED FOR PADDLED VEHICLES AND APPARATUS. [1792] The inventions are related to electric paddled vehicles, for land vehicles and water vehicles. Comprising, at least one Wheel mounted in the frame fork. At least one Back wheel mounted in the fork of the frame. The at least one front wheel and/or back-wheel having an electric hub motor and/or generator. Pair of paddles connected by a paddle rod mounted on the frame in a closed casing. Operable suspended in bearings in the casing of the lower frame including a cam driving a chain drive mashing with cams of gears and chain tensioner. Without cams and chain, or belt. V-belt. Castellated belt. Wherein the rod stationary and tubular casing the Coaxial arranged automated gearbox, made on the dual ratchet shafts, and electric machine, arranged with a plurality of magnets and opposing induction coils with an air gap to the opposing rotor which are mated with a pinion extending from the casing. Pinion mashing with the circular racks provided on the outer rotors of the electric machine part rotating in opposite direction, connected by gears to the paddle second ratchet barrel. Rotary paddle or linear paddle, Linear paddle with coaxial machine and hub motors and/or hub generator rotated by a rack and pinion and/or reciprocating mechanism. [0000] The electric generator is mounted in the frame stator body of the on the rotary paddle comprising a hub motor or a geared electric machine. The wheel comprises the electric magnet motor and generator that supply power from the stator coils to the second wheel and the second hub motor supply electricity to the power supply. -

23Rd Annual Antique & Classic Bicycle Auction

CATALOG PRICE $4.00 Michael E. Fallon / Seth E. Fallon COPAKE AUCTION INC. 266 Rt. 7A - Box H, Copake, N.Y. 12516 PHONE (518) 329-1142 FAX (518) 329-3369 Email: [email protected] Website: www.copakeauction.com 23rd Annual Antique & Classic Bicycle Auction Featuring the David Metz Collection Also to include a selection of ephemera from the Pedaling History Museum, a Large collection of Bicycle Lamps from the Midwest and other quality bicycles, toys, accessories, books, medals, art and more! ************************************************** Auction: Saturday April 12, 2014 @ 9:00 am Swap Meet: Friday April 11th (dawn ‘til dusk) Preview: Thur. – Fri. April 10-11: 11-5pm, Sat. April 12, 8-9am TERMS: Everything sold “as is”. No condition reports in descriptions. Bidder must look over every lot to determine condition and authenticity. Cash or Travelers Checks - MasterCard, Visa and Discover Accepted First time buyers cannot pay by check without a bank letter of credit 17% buyer's premium (2% discount for Cash or Check) 20% buyer's premium for LIVE AUCTIONEERS Accepting Quality Consignments for All Upcoming Sales National Auctioneers Association - NYS Auctioneers Association CONDITIONS OF SALE 1. Some of the lots in this sale are offered subject to a reserve. This reserve is a confidential minimum price agreed upon by the consignor & COPAKE AUCTION below which the lot will not be sold. In any event when a lot is subject to a reserve, the auctioneer may reject any bid not adequate to the value of the lot. 2. All items are sold "as is" and neither the auctioneer nor the consignor makes any warranties or representations of any kind with respect to the items, and in no event shall they be responsible for the correctness of the catalogue or other description of the physical condition, size, quality, rarity, importance, medium, provenance, period, source, origin or historical relevance of the items and no statement anywhere, whether oral or written, shall be deemed such a warranty or representation. -

Or How I Learned to Love Riding a Recumbent

by Larry Strattner Getting Bent or How I Learned to Love Riding a Recumbent My long, winding journey to becoming the first time bought a road bicycle. I spent an automobile. Here’s how I made my pur- is getting used to a total change in how day-glow flag on a fiberglass pole to make power sliding my Specialized Roubaix road a recumbent cyclist began in the 1960s, several years riding long miles on the beau- chase decision. you ride a bike. I selected my favorites in me feel safe down near the asphalt in cell- bike, I have never been a lover of squirre- when I began endurance racing motor- tiful back roads of Wisconsin with these I first considered designs. Like it or not, this area and then got down to some more phone-talking, SUV-driving America. ly and harsh 700x23 high-pressure tires. cycles in the New England woods. Around folks until a couple of them moved away. as the car-market guys have known forever, tangible concerns. I didn’t like the look of a 26-inch or Something about steering at or below seat the early 1980s, I gave it up because I At the same time, I got a promotion at and this sex/image/expectation stew is a big I didn’t like the idea of being too low to 700cc wheel in the rear and a 20-inch wheel level just plain scared me. I know it’s com- moved to Minnesota. They aren’t kidding spent a year working a lot of hours. -

Cyclist GO the DISTANCE

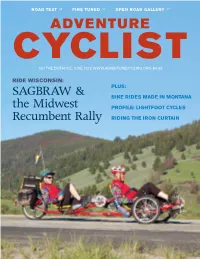

ROAD TEST 36 FINE TUNED 40 OPEN ROAD GALLERY 47 ADVENTURE CYCLIST GO THE DISTANCE. JUne 2012 WWW.ADVentURecYCLing.ORG $4.95 RIDE WISCONSIN: PLUS: SAGBRAW & BIKE RIDES MADE IN MONTANA the Midwest PROFILE: LIGHTFOOT CYCLES Recumbent Rally RIDING THE IRON CURTAIN Share the Joy GET A CHANCE TO WIN 6:2012 contents Spread the joy of cycling and get a chance to win cool prizes June 2012 · Volume 39 Number 5 · www.adventurecycling.org n For each cyclist you refer to Adventure Cycling, you will ADVENTURE get one chance to win a Giant Rapid 1* valued at over $1,250. The winner will be drawn from all eligible CYCLIST members in January of 2013. is published nine times each year by the Adventure Cycling Association, n Each month, we’ll draw a mini-prize winner who a nonprofit service organization for recreational bicyclists. Individual will receive gifts from Old Man Mountain, Arkel, membership costs $40 yearly to U.S. Ortlieb, and others. addresses and includes a subscrip- tion to Adventure Cyclist and dis- n The more new members you sign up, the more counts on Adventure Cycling maps. chances you have to win! The entire contents of Adventure Cyclist are copyrighted by Adventure Cyclist and may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written * Bicycle model may change with release of new or updated models. permission from Adventure Cyclist. All rights reserved. Adventure Cycling Association adventurecycling.org/joy OUR COVER Cycle Montana riders clip along on their recumbent tandem trike. Photo by Greg Siple. Y (left) A cyclist winds through the HANE forest on the Whitefish Trail in Adventure Cycling Corporate Members K C U Montana. -

Albuquerque Morning Journal, 11-29-1912 Journal Publishing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 11-29-1912 Albuquerque Morning Journal, 11-29-1912 Journal Publishing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_mj_news Recommended Citation Journal Publishing Company. "Albuquerque Morning Journal, 11-29-1912." (1912). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ abq_mj_news/2586 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALBUQUERQUE MORNING JOURNAL. bU ft R Ui Mall, Cents Mouth; Hlngle Oopleg ocdM, THIRTY-FOURT- H YEAR. VOL CXXXVI, No. ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO, FRIDAY, NOT Mh'l :n I'M: 60. Hj Carrier, 6U fonla Month. the murder of hti sweetheart, Helen I the right-han- d boViet a palm branch. pouru an Infernal f,r Into tin . I , in nun,' in i iii:i, was given The one-- cut stamp la green iind In works Bight) thouaand lOldleri arc RELEASE IS , DURAZZO T PATRICKOM commutation of sentence today in THANKSGIVING the enter appear within a circle it shut P III illfanople ,i the pi,, BRITAIN PROPOSES fifteen year by Acting Qovernor hust of 1,'uihim. dlacoverer of the Pa-eif- ie visions caunoi last u eh longer, ocean, looking .Many Lelghtoii. Since ii is confinement In '" " ''" trenches in, protected hy wire wearing a culraaj attil a helmet with and dome of them are only ISO ynrdi the penitentiary Beckman has sent A F ROM SIN money regularly to organi- CELEBRATED a plume, ADRIATIC S IS front the heNlcKCis who are pressing CONFERENCE OF charitable two-ce- , IE zations and worths lufferert through- The nt stamp is red. -

MBCUK LOG BOOK 5Th Edition March 2014

MBCUK LOG BOOK 5th Edition March 2014 MISSION STATEMENT TO PROVIDE PROFESSIONAL MOUNTAINBIKE COACHING, LEADER AND SKILLS AWARDS, IN A SAFE, ENJOYABLE AND LEARNING ENVIRONMENT DEVELOPING AND SHARING BEST PRACTICE TO ENABLE AWARD HOLDERS TO PASS ON THEIR EXPERIENCES TO THE WIDER CYCLING COMMUNITY Chip Rafferty (MA) Managing Director MBCUK 2 Contents Registration page 02 Foreword page 03 Matrix page 06 Syllabus page 07 • The Mountain Bike • Riding Types • Optimum Position • The Safe Cycle • Cycle Maintenance • Clothing and Equipment • On Road Safety Guidelines • Skills Test • Access and Conservation • Navigation • Planning your trip Cycling Disciplines page 20 Course Description page 23 MBCUK Mountain Biking Trail Grading page 29 Biking logbook page 30 Annexes • Risk Assessment Guidelines page 35 • Mountain Biking Risk Assessment page 36 • Vulnerability Guidelines page 37 • Skills Course Layout page 38 • Skills Test Score Card page 39 • Mountain Biking Route Card page 40 • Skill Levels page 41 • MBCUK Accident Report page 42 • Bike Checklist page 43 • Coaching Tips page 46 • Coach Checklist page 47 • Rider Profile page 48 • Course Questionnaire page 50 • ABCC Registration Renewal page 52 2 Registration Name Address Date of Birth Date of Enrolment approved Registration number sticker Training and Assessment Matrix and Record (See page 23) LEVEL LOCATION DATE TUTOR MBCUK sticker Training TL approved sticker Assessment TL approved sticker Training TTL approved sticker Assessment TTL sticker TTL Expedition Module TTL (E) sticker Training MBC approved sticker Assessment MBC approved sticker Tutor approved sticker First Aid Certificate Issued by Expires 3 MBCUK Mountain Bike Coach Awards Foreword The Mountain Bike Coaching UK MBCUK awards scheme exists to improve mountain bikers awareness of the knowledge and skills required to coach and lead on bikes with optimum safety education and comfort. -

MBCUK LOG BOOK 7Th Edition Nov 2019

MBCUK LOG BOOK 7th Edition Nov 2019 MISSION STATEMENT TO PROVIDE PROFESSIONAL MOUNTAINBIKE COACHING, LEADER AND SKILLS AWARDS, IN A SAFE, ENJOYABLE AND LEARNING ENVIRONMENT DEVELOPING AND SHARING BEST PRACTICE TO ENABLE AWARD HOLDERS TO PASS ON THEIR EXPERIENCES TO THE WIDER CYCLING COMMUNITY Chip Rafferty (MA) Managing Director MBCUK 01 Contents Registration page 02 Foreword page 03 Matrix page 06 Syllabus page 07 • The Mountain Bike • Riding Types • Optimum Position • The Safe Cycle • Cycle Maintenance • Clothing and Equipment • On Road Safety Guidelines • Skills Test • Access and Conservation • Navigation • Planning your trip Cycling Disciplines page 20 Course Description page 23 MBCUK Mountain Biking Trail Grading page 29 Biking logbook page 30 Annexes • Risk Assessment Guidelines page 35 • Mountain Biking Risk Assessment page 36 • Vulnerability Guidelines page 37 • Skills Course Layout page 38 • Skills Test Score Card page 39 • Mountain Biking Route Card page 40 • Skill Levels page 41 • MBCUK Accident Report page 42 • Bike Checklist page 43 • Quality Mountain Bike Ride page 44 • Coaching Tips page 46 • Coach Checklist page 47 • Rider Profile page 48 • Course Questionnaire page 50 • ABCC Registration Renewal page 52 02 Registration Name Address Date of Birth Date of Enrolment approved Registration number sticker Training and Assessment Matrix and Record (See page 23) LEVEL LOCATION DATE TUTOR MBCUK sticker Training TL approved sticker Assessment TL Level 1 approved sticker Training TTL approved sticker Assessment TTL sticker TTL Level 2 Expedition Module TTL (E) sticker Training MBC approved sticker Assessment MBC Level 3 approved sticker Tutor approved sticker First Aid Certificate Issued by Expires 03 MBCUK Mountain Bike Coach Awards Foreword The Mountain Bike Coaching UK MBCUK awards scheme exists to improve mountain biker’s awareness of the knowledge and skills required to coach and lead on bikes with optimum safety education and comfort. -

Mountain Biking Curriculum Guide Table of Contents

Mountain Biking Curriculum Guide Table of Contents I. Introduction Pg. 3 II. Sport Specific Challenges & Considerations Pg 3. III. Equipment Pg. 5 IV. Participant Preparedness Pg. 8 V. Environment & Terrain Pg. 9 VI. Safety & Liability Pg. 11 VII. Functional Destinations Pg. 12 VIII. Mountain Biking Skills Pg. 13 IX. Incorporating Nature Pg. 53 X. Games & Activities Pg. 54 XI. Lesson Plans Pg. 59 XII. Resources & References Pg. 71 2 I. Introduction Nothing compares to the simple pleasure of a bike ride. ~John F. Kennedy Despite our best efforts, the inherent joy of outdoor recreation can sometimes be lost on beginners. This typically isn’t the case when it comes to riding a bike. Balancing on two wheels, coasting along, feeling the breeze on your face – these are the simple pleasures of cycling that do not have to be explained. Combine these elements with the experience of being on a wooded trail, in and amongst nature, and you have a sport with instant appeal and immediate reward: mountain biking. As a sport, mountain biking continues to grow in popularity across the globe. Well-run youth programs can pro- vide a powerful entry-point to this life-long activity. This curriculum guide is designed to to be a resource for lead- ers of introductory mountain bike programs. Within these pages you will find information that will be applicable to both school-based and extra curricular settings. The following information will be most helpful when supplemented with an Outdoor Sport Institute (OSI) edu- cational workshop. To find out where and when these workshops are happening, visit us online at outdoorsportin- stitute.org Here you can also learn more about using OSI equipment, including mountain bikes, canoes, kayaks, skis, and more. -

Status Quo Und Erfahrungen Mit Der Planung Und Dem Betrieb Von Radschnellwegen in Den Niederlanden, Dänemark, Großbritannien Und Deutschland

Status Quo und Erfahrungen mit der Planung und dem Betrieb von Radschnellwegen in den Niederlanden, Dänemark, Großbritannien und Deutschland Ineke Spapé, Christine Fuchs, Jürgen Gerlach Verfasseranschriften: Ir. Ineke Spapé (Dipl. Ing.) SOAB Consultants und NHTV, University for Applied Sciences Breda Belcrumwatertoren, Speelhuislaan 158 NL-4815 CJ Breda [email protected] Christine Fuchs Arbeitsgemeinschaft fußgänger- und fahrradfreundlicher Städte, Gemeinden und Kreise in NRW e.V. Vorstand AGFS im Rathaus der Stadt Krefeld Von-der-Leyen-Platz 1 47798 Krefeld [email protected] Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. Jürgen Gerlach Bergische Universität Wuppertal Fachbereich D - Abteilung Bauingenieurwesen Lehr- und Forschungsgebiet Straßenverkehrsplanung und Straßenverkehrstechnik Pauluskirchstrasse 7 42285 Wuppertal [email protected] Aktuell sind in Deutschland zahlreiche Radschnellwegprojekte zu verzeichnen. Radschnell- wege sollen bei Investitionsaufwendungen, die je nach Planungskonzept, Voraussetzung und Anzahl von Brücken und Tunnel zwischen rd. 0,5 und 2,0 Mio. Euro pro km liegen, ein zügiges, attraktives und sicheres Radfahren in einem Entfernungsbereich von bis zu rd. 20 km gewährleisten und Verlagerungen insbesondere von Kfz-bezogenen Berufspendlerver- kehren bewirken. Erfahrungen mit derzeit 18 realisierten Radschnellstrecken in den Nieder- landen, zwei realisierten Radschnellverbindungen in Dänemark und enormen Anstrengungen zum Aufbau einer hochwertigen Radverkehrsinfrastruktur in Großbritannien zeigen, dass diese Ziele in bemerkenswerter Weise erreicht werden. Radschnellwege werden insofern auch in Deutschland ein sinnvoller und schon recht bald ein fester Bestandteil des Rad- wegenetzes sein. Status Quo and experience with the planning and operation of cycle highways in the Netherlands, Denmark, Great Britain and Germany Numerous projects of cycle highways can be recorded in Germany at the moment. Cycle highways require investments between 0.5 and 2.0 million Euros per km - depending on the planning concept, condition and number of bridges and tunnels. -

Trail Threads

DIESELBIKES Volume 2, Issue 8 August 2008 Trail Threads Lynn Woods: Lynn, MA It has been another quite month in Lynn Woods and even with all the rain we have had, the majority of trails are looking great. There are a few spots of rain battered trail erosion but nothing that is of major concern. Re- member, we will be re-starting our annual trail projects in September, so get your shovels and picks ready because we have two large projects left to finish. We do not have anything further to report regarding the land development occurring on the North Side of Lynn Woods in Lynnfield. Construction is fast and since last month, framing for a number of buildings have gone up taking away from the beautiful landscape. The construction will not come any closer to the well know area called “The Playground” in Lynnfield, but riding those trails and seeing such large buildings so close is a sad site. The power company is still working on the power lines and will be finishing up in a few months. If you are riding on Shark’s Tooth Trail near Route 1, you probably notice that someone has clear cut a number of trees. This section was cleared by the power company to keep tree limbs from contacting the smaller power line wires running parallel to Route 1 north. We have been out cleaning up some of the mess left on the trail during our Tuesday rides, so this section is get- ting back into shape, but it is still is little beat up from all the work.