Radical Protest in Cold-War West Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Balancing Security and Liberty in Germany

Balancing Security and Liberty in Germany Russell A. Miller* INTRODUCTION Scholarly discourse over America’s national security policy frequently invites comparison with Germany’s policy.1 Interest in Germany’s national security jurisprudence arises because, like the United States, Germany is a constitutional democracy. Yet, in contrast to the United States, modern Germany’s historical encounters with violent authoritarian, anti-democratic, and terrorist movements have endowed it with a wealth of constitutional experience in balancing security and liberty. The first of these historical encounters – with National Socialism – provided the legacy against which Germany’s post-World War II constitutional order is fundamentally defined.2 The second encounter – with leftist domestic radicalism in the 1970s and 1980s – required the maturing German democracy to react to domestic terrorism.3 The third encounter – the security threat posed in the * Associate Professor of Law, Washington & Lee University School of Law ([email protected]); co-Editor-in-Chief, German Law Journal (http://www.germanlaw journal.com). This essay draws on material prepared for a forthcoming publication. See DONALD P. KOMMERS & RUSSELL A. MILLER, THE CONSTITUTIONAL JURISPRUDENCE OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY (3rd ed., forthcoming 2011). It also draws on a previously published piece. See Russell A. Miller, Comparative Law and Germany’s Militant Democracy, in US NATIONAL SECURITY, INTELLIGENCE AND DEMOCRACY 229 (Russell A. Miller ed., 2008). The essay was written during my term as a Senior Fulbright Scholar at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and Public International Law in Heidelberg, Germany. 1. See, e.g., Jacqueline E. Ross, The Place of Covert Surveillance in Democratic Societies: A Comparative Study of the United States and Germany, 55 AM. -

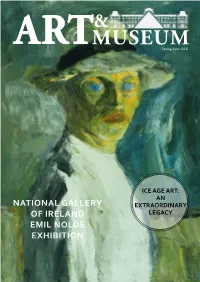

MUSEUM ART Spring Issue 2018

& MUSEUM ART Spring Issue 2018 ICE AGE ART: AN NATIONAL GALLERY EXTRAORDINARY OF IRELAND LEGACY EMIL NOLDE EXHIBITION CONTENTS 12 ANGELA ROSENGART 14 Interview with Madam Rosengarth about the Rosengarth Museum IVOR DAVIES Inner Voice of the Art World 04 18 NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND SCULPTOR DAWN ROWLAND Sean Rainbird CEO & Editor Director National Gallery of Ireland Siruli Studio WELCOME Interviewed by Pandora Mather-Lees Interview with Derek Culley COVER IMAGE Emil Nolde (1867-1956) Self-portrait, 1917 ART & MUSEUM Magazine and will also appear at many of Selbstbild, 1917 Oil on plywood, 83.5 x 65 cm MAGAZINE the largest finance, banking and Family © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll Office Events around the World. Welcome to Art & Museum Magazine. This Media Kit. - www.ourmediakit.co.uk publication is a supplement for Family Office Magazine, the only publication in the world We recently formed several strategic dedicated to the Family Office space. We have partnerships with organisations including a readership of over 46,000 comprising of some The British Art Fair and Russian Art of the wealthiest people in the world and their Week. Prior to this we have attended and advisors. Many have a keen interest in the arts, covered many other international art fairs some are connoisseurs and other are investors. and exhibitions for our other publications. Many people do not understand the role of We are very receptive to new ideas for a Family Office. This is traditionally a private stories and editorials. We understand wealth management office that handles the that one person’s art is another person’s investments, governance and legal regulation poison, and this is one of the many ideas for a wealthy family, typically those with over we will explore in the upcoming issues of £100m + in assets. -

Olaf Jahnke RAF Topographie Kurz

Rote Armee Fraktion Topographie Olaf Jahnke Olaf Jahnke olafjahnke.de Druck und Bindung: MJ Raak, Frankfurt DievorliegendePublikationisturheberrechtlichgeschützt. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dies gilt insbesondere für die Vervielfältigung, Übersetzung oder VerwendunginelektronischenSystemen. Rote Armee Fraktion AlleAngabenindiesemBuchwurdenmitgrößterSorgfaltkontrolliert. Der Autor kann nicht haftbar gemacht werden für Schäden, die in Zusammenhang mit diesem Buch stehen. Topographie Künstleredition, Auflage 99 + 5 E.A. Vorwort Dr. Barbara Perfahl Frankfurt und Umgebung die-wohnpsychologin.de Mit einem Vorwort von Dr. Barbara Perfahl Das Gesamtprojekt wurde gefördert durch ein Stipendium der Hessischen Kulturstiftung. März 2021 Einleitung Seit 1982 arbeite ich in Frankfurt, habe auch einige Jahre hier gewohnt. Speziell ältere Kollegen erzählten mir früher, dass damals in der einen oder anderen Ecke Frankfurts Mitglieder der RAF einen Unterschlupf gefunden hatten. Meistens wurde von Bornheim oder, etwas konkreter, der Berger Straße gesprochen. Die Taten der Gruppe im Hinterkopf, lief mir dann ein Schauer über den Rücken, beim Gedanken, dort unwissentlich möglicherweise einem Terroristen begegnet zu sein. Wenn es mir bereits so geht, wie müssen sich die Betroffenen fühlen? Polizisten, die in einen Schusswechsel mit den Mitgliedern der RAF gerieten oder nach den Anschlägen die grausame Wirkung von Bomben sahen, ganz zu schweigen natürlich von den Opfern selbst und ihren Angehörigern, sie leiden ein Leben lang unter den Folgen. Mit der RAF bringt man wahrscheinlich eher Berlin oder bestimmte Anschlagsorte wie Karlsruhe in Verbindung. Umso überraschter war ich zu Beginn meiner Recherche bei der Lektüre des Standardwerks „Der Baader-Meinhof-Komplex“ von Stefan Aust. Hier schreibt Aust ganz deutlich, dass Andreas Baader sehr schnell Frankfurt als neues Hauptquartier ausgewählt hatte. West-Berlin war Baader aufgrund der Inselsituation zu eng geworden, in Hamburg hatte die Gruppe bereits einige Rückschläge erlitten. -

KHS Die Rolleberlins Innerhalb Der Ost-West-Kompetenz Der

Standke: Ost-West Kompetenz Berlins 3 Klaus-Heinrich Standke Die Rolle Berlins innerhalb der Ost-West-Kompetenz der Bundesländer Arbeitspapiere des Osteuropa-Instituts der Freien Universität Heft 12/2000 Vorwort des Herausgebers Die neue Rolle Berlins nach dem Mauerfall, nach dem Umzug von Bundestag und Bundesregierung und nicht zuletzt nach dem Eintritt in die intensive Verhandlungsphase der Osterweiterung der Europäischen Union ist Gegenstand nationaler und internationaler Diskussion. Berlin ist nicht nur als Deutschlands Hauptstadt der Gegenwartsarchitektur, sondern in seiner vielzitierten politischen Mittlerfunktion zwischen West- und Osteuropa sicherlich noch nicht am Ziel. Die mit der Osterweiterung einhergehende Ostverschiebung der europäischen Politik schafft mittel- und langfristig für diese neue Rolle der Stadt gute Rahmenbedingungen, die es freilich zu nutzen gilt. Doch welches sind die Voraussetzungen, die Berlin selbst für diese seine Rolle als Ost-West-Metropole gegenwärtig besitzt, welche wirtschaftlichen, politischen, wissenschaftlichen, administrativen und personellen Ressourcen kann die deutsche Hauptstadt im Wettbewerb mit anderen europäischen Zentren bieten und aktivieren? Die Suche nach fundierten Antworten verlangt zunächst eine genaue Bestandsaufnahme. Hier und bei seinen Antworten betritt der Autor Neuland insofern, als eine vergleichbar genaue, faktengesättigte und systematische Untersuchung bisher fehlt. Nicht nur Studierende des Osteuropa-Instituts der Freien Universität Berlin, sondern auch Politiker, Wirtschaftler -

Considering the Creation of a Domestic Intelligence Agency in the United States

HOMELAND SECURITY PROGRAM and the INTELLIGENCE POLICY CENTER THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Homeland Security Program RAND Intelligence Policy Center View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. -

Tradition Biloxi, Mississippi

A SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT PANEL REPORT Tradition Bi lo xi, Mississi ppi Urban L an d $ Ins ti tute Tradition Biloxi, Mississippi Developing a Sustainable Master-Planned Community January 13 –18, 2008 A Sustainable Development Panel Report ULI–the Urban Land Institute 1025 Thomas Jefferson Street, N.W. Suite 500 West Washington, D.C. 20007-5201 About ULI–the Urban Land Institute he mission of the Urban Land Institute is to • Sustaining a diverse global network of local provide leadership in the responsible use of practice and advisory efforts that address cur - land and in creating and sustaining thriving rent and future challenges. T communities worldwide. ULI is committed to Established in 1936, the Institute today has more • Bringing together leaders from across the fields than 40,000 members worldwide, represent ing t he of real estate and land use policy to exchange entire spectrum of the land use and develop ment best practices and serve community needs; disciplines. Professionals represented include de - velopers, builders, property owners, investors, ar - • Fostering collaboration within and beyond chitects, public officials, planners, real estate bro - ULI’s membership through mentoring, dia - kers, appraisers, attorneys, engineers, financiers , logue, and problem solving; academics, students, and librarians. ULI relies • Exploring issues of urbanization, conservation, heavily on the experience of its members. It is regeneration, land use, capital formation, and through member involvement and information sustainable development; resources that ULI has been able to set standards of excellence in development practice. The Insti - • Advancing land use policies and design prac - tute has long been recognized as one of the world’s tices that respect the uniqueness of both built most respected and widely quoted sources of ob - and natural environments; jective information on urban planning, growth, and development. -

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, and NOWHERE: a REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY of AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS by G. Scott Campbell Submitted T

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS BY G. Scott Campbell Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________ Chairperson Committee members* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* Date defended ___________________ The Dissertation Committee for G. Scott Campbell certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS Committee: Chairperson* Date approved: ii ABSTRACT Drawing inspiration from numerous place image studies in geography and other social sciences, this dissertation examines the senses of place and regional identity shaped by more than seven hundred American television series that aired from 1947 to 2007. Each state‘s relative share of these programs is described. The geographic themes, patterns, and images from these programs are analyzed, with an emphasis on identity in five American regions: the Mid-Atlantic, New England, the Midwest, the South, and the West. The dissertation concludes with a comparison of television‘s senses of place to those described in previous studies of regional identity. iii For Sue iv CONTENTS List of Tables vi Acknowledgments vii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Mid-Atlantic 28 3. New England 137 4. The Midwest, Part 1: The Great Lakes States 226 5. The Midwest, Part 2: The Trans-Mississippi Midwest 378 6. The South 450 7. The West 527 8. Conclusion 629 Bibliography 664 v LIST OF TABLES 1. Television and Population Shares 25 2. -

Premio Europeo Capo Circeo Xxxiii Edizione

Quilici -Hans Peter Kleefuss - Sorelle Kessler - Gianni Testoni - Klaus Rauen - Walter Tocci - Rolf Gallus - Werner Hoyer - Hans Georg Gadamer - Franco Volpi - XXXIII EDIZIONE Gerardo Marotta - Nico Cambareri -Robert Bùchelhofer - Vittorio Cecchi Gori - Giuseppe Marra -Gennaro Malgieri - Daniel Barenboim - Adriano Aragozzini PREMIO -Woifram Thomas - Virna Lisi - Gabriella Carlucci - Gianni Borgna - Ludwig Scholtz - Karl Heinz Kuhna - Mario Luzi - Giacomo Marramao - Stanislao Nievo - EUROPEO Klaus Hempfer - Gert Mattenklott -Barthold C. Witte - Ferdinand Pièch - Roberto Tana - Vaclav Havel - Jiri Pelikan - Sergio Romano - Salvo Mazzolini - Luciano Rispoli - Marcello Veneziani - Wolf Lepenies - Walter Maestosi -Manfred Buche - CAPO Claudio Magris - Klaus Borchard - Vladimir Bukovsky - Johann Wohlfarter - Siegfried Sobotta - Rudy Peroni - Fritjof Von Nordenskjöld - Enzo Perlot - Piero CIRCEO Ostellino - Enzo Piergianni - Claus Theo Gàrtner - Fausto Bruni - Gaetano M. Fara - Claudio D'Arrigo - Alberto Indelicato - Harry Blum - Werner Keller - Giovanni CONTINUITÀ Sartori - Emanuele Severino - Vittorio Mathieu -Mario Monti - Matthias Wissmann - Uwe Lehman-Brauns -Giuseppe Vegas - Arrigo Levi - Albert Scharf - Mario IDEALE Nordio Lothar Hòbelt - Christian Ude - Gedeon Burkhard - Doris Maurer - Franz E STORICA Schenk Von Stauffenberg - Paolo Giuliani - Viktor Orbàn - Pier Ferdinando Casini - Paul Mikat - Peter Esterhazy - Luciano De Crescenzo - Norbert Miller - Anna Masala - Hermann Teusch - Aldo Di Lello - Henning Schulte-Noelle - Joachim Milberg -

State of the (Student) Union Address

12 smallTALK w March 7, 2011 Volume 50, Issue 10 TNA Q & A with ONARCH iMPACT President COREBOARD hits Hancock M Fayetteville ...page 3 S ...page 6 GAME RESULTS small ALK Baseball March 7, 2011 The sTudenT voice of MeThodisT universiTy Methodist University Date Opponent Result Volume 50, Issue 10 Fayetteville, NC 2/23 Hampden-Sydney College W 7-4 T 2/26 LaGrange College W 8-1 www.sMallTalkMu.coM 2/27 LaGrange College W 8-3 3/1 Immaculata University W 14-1 3/2 Lynchburg College W 12-0 Softball Date Opponent Result State of the (Student) Union Address 2/25 Piedmont College L 1-3 2/25 Lynchburg College L 4-7 2/26 Salisbury University L 2-9 President Hancock answers students’ questions at Town Hall Meeting 2/26 Eastern Mennonite University W 2-0 2/27 Roanoke College L 1-13, L 5-13 of a university,” Hancock said to the crowd. “I think I have the best job in America, and I Men’s Tennis want each and every one of you to feel like you are at the best school in America.” Date Opponent Result “I’ve been waiting 27 years for Dr. Hendricks to retire,” joked Hancock. “And now, 2/23 Barton College L 4-5 just a little older than 52, I am here doing exactly what I set my sight on so long ago.” 2/26 Benedict College W 9-0 Hancock explained to the crowd that he would attempt to answer every question to the 2/26 Guilford College W 8-1 3/3 Mount Olive College L 1-8 best of his ability, but asked students to be patient with him if he did not know the answer and promised that he would do his best to answer questions as he learned more about Women’s Tennis Methodist University. -

Black Hands / Dead Section Verdict

FRINGE REPORT FRINGE REPORT www.fringereport.com Black Hands / Dead Section Verdict: Springtime for Baader-Meinhof London - MacOwan Theatre - March 05 21-24, 29-31 March 05. 19:30 (22:30) MacOwan Theatre, Logan Place, W8 6QN Box Office 020 8834 0500 LAMDA Baader-Meinhof.com Black Hands / Dead Section is violent political drama about the Baader-Meinhof Gang. It runs for 3 hours in 2 acts with a 15 minute interval. There is a cast of 30 (18M, 12F). The Baader-Meinhof Gang rose during West Germany's years of fashionable middle-class student anarchy (1968-77). Intellectuals supported their politics - the Palestinian cause, anti-US bases in Germany, anti-Vietnam War. Popularity dwindled as they moved to bank robbery, kidnap and extortion. The play covers their rise and fall. It's based on a tight matrix of facts: http://www.fringereport.com/0503blackhandsdeadsection.shtml (1 of 7)11/20/2006 9:31:37 AM FRINGE REPORT Demonstrating student Benno Ohnesorg is shot dead by police (Berlin 2 June, 1967). Andreas Baader and lover Gudrun Ensslin firebomb Frankfurt's Kaufhaus Schneider department store (1968). Ulrike Meinhof springs them from jail (1970). They form the Red Army Faction aka Baader-Meinhof Gang. Key members - Baader, Meinhof, Ensslin, Jan- Carl Raspe, Holger Meins - are jailed (1972). Meins dies by hunger strike (1974). The rest commit suicide: Meinhof (1976), Baader, Ensslin, Raspe (18 October 1977). The play's own history sounds awful. Drama school LAMDA commissioned it as a piece of new writing (two words guaranteed to chill the blood) - for 30 graduating actors. -

The Eagle 2005

CONTENTS Message from the Master .. .. .... .. .... .. .. .. .. .. .... ..................... 5 Commemoration of Benefactors .. .............. ..... ..... ....... .. 10 Crimes and Punishments . ................................................ 17 'Gone to the Wars' .............................................. 21 The Ex-Service Generations ......................... ... ................... 27 Alexandrian Pilgrimage . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .................. 30 A Johnian Caricaturist Among Icebergs .............................. 36 'Leaves with Frost' . .. .. .. .. .. .. ................ .. 42 'Chicago Dusk' .. .. ........ ....... ......... .. 43 New Court ........ .......... ....................................... .. 44 A Hidden Treasure in the College Library ............... .. 45 Haiku & Tanka ... 51 and sent free ...... 54 by St John's College, Cambridge, The Matterhorn . The Eagle is published annually and other interested parties. Articles members of St John's College .... 55 of charge to The Eagle, 'Teasel with Frost' ........... should be addressed to: The Editor, to be considered for publication CB2 1 TP. .. .. .... .. .. ... .. ... .. .. ... .... .. .. .. ... .. .. 56 St John's College, Cambridge, Trimmings Summertime in the Winter Mountains .. .. ... .. .. ... ... .... .. .. 62 St John's College Cambridge The Johnian Office ........... ..... .................... ........... ........... 68 CB2 1TP Book Reviews ........................... ..................................... 74 http:/ /www.joh.cam.ac.uk/ Obituaries -

How Sweet Is the Future

CHOCOLATE VERSUS SUGAR We observe that the importance of chocolate products in relation to sugar products as a whole is highest in Germany, Austria and Norway. How Sweet is the Future However, the chocolate products’ market in these countries is not uni- Internationalization/expansion fied and appears to be diversified within the product classes. For instance, Germans are the biggest consumers of pralines, which accounts for nearly 40 percent of Renate Sander the total consumption of chocolate A.C. Nielsen GmbH products, with tablets representing 31 percent. In Austria it is exactly the opposite. However, Scandina- vians, Irish and Dutch pay more for chocolate bars. In Spain, which comes last in Europe as far as chocolate products are concerned, we note that bars are or producers, internationaliza- In preparation for this report we far below the average at only 7 per- Ftion and expansion towards had access to data from 32 countries cent. This is no surprise if we take into other countries is mostly no longer where we have regular reporting on consideration that, for most large an option, but a question of survival. confectionery. These countries rep- international suppliers of bars, the The battle against the rise of raw resent nearly half (46%) of the Spanish market represents a weak material prices and the multiplica- world population, i.e., about 2.6 bil- spot in their European activities. tion of difficulties in achieving high- lion inhabitants. Among Asian countries, the Chi- er prices at trade level, and thus, the In an attempt to be clearer we nese market is a dark blot on the pressure linked to profit, force pro- divided the confectionery market chocolate products horizon.