The Bare Bones of the Argument

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard of York Gives Battle Again

Richard of York Gives Battle Again Andrew Hogan About 40 miles from here, in 1485, Richard III unwittingly brought the Middle Ages to an end by losing the Battle of Bosworth Field to the victorious Henry Tudor. The defeated king’s remains were taken to Leicester and lost. Found in 2013, the Divisional Court on 26th November 2013 will hear the substantive challenge brought in relation to their re-interment and location of the dead king’s final resting place. The challenge brought by the Plantagenet Alliance Limited has already generated some interesting ancillary litigation in the field of protective costs orders: on 15th August 2013 Mr Justice Haddon-Cave granted permission to bring judicial review and also made a protective costs order on the papers. On 26th September 2013 the court heard a number of applications, including one to vary or discharge the protective costs order. In a full and careful judgment given on 18th October 2013 the court handed down its reasoned judgment reported at [2013] EWHC 3164 (Admin). The Law Relating to Protective Costs Orders The learned judge began by restating the substantive law that prescribes when and in what circumstances the court will exercise its discretion to make a predictive costs order: 17. The general principles governing Protective Costs Ordered were restated by the Court of Appeal in R (Corner House) v Secretary of State for Trade and Industry [2005] 1 WLR 2600 (CA) at [74] as follows (see also The White Book at paragraph 48.15.7): (1) A protective costs order may be made at any stage of -

Judicial Review in England and Wales: a Constructive Interpretation of the Role of the Administrative Court

TITLE: JUDICIAL REVIEW IN ENGLAND AND WALES: A CONSTRUCTIVE INTERPRETATION OF THE ROLE OF THE ADMINISTRATIVE COURT Sarah Marie Nason University College London PHD 1 DECLARATION OF AUTHENTICITY ‘ I, Sarah Marie Nason confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed… ………………………….. Date…15 October 2014…………………………….. 2 ABSTRACT In this thesis I construct an interpretation of judicial review in England and Wales from the ground up based on an analysis of social practice in the Administrative Court. I argue that whilst judicial review provides a forum for debates about constitutional values and rights, and the inter-institutional balance of power between different branches of state, it is still primarily concerned with doing justice for individuals in relatively non-complex cases. Both in highly contested and technical claims with broader implications, and in cases turning largely on their own facts, justice is done by way of ordinary common law reasoning and specifically by assessing whether the initial decision-maker has taken relevant considerations (including moral considerations) into account, and excluded irrelevant considerations. My first central argument is that some existing interpretations of judicial review display a lack of appreciation of the social facts of litigation and legal practice, whilst others are based on significant misconceptions about these facts. My second central argument is against the scholarly tendency to over- emphasise the production and refinement of conceptual doctrinal tests at the expense of addressing the contested nature of the moral values at stake in the practice of judicial review as a whole and in individual cases. -

Ricardian Bulletin March 2014 Text Layout 1

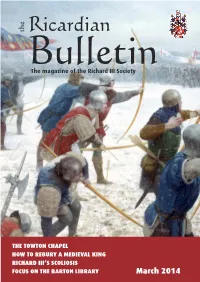

the Ricardian Bulletin The magazine of the Richard III Society THE TOWTON CHAPEL HOW TO REBURY A MEDIEVAL KING RICHARD III’S SCOLIOSIS FOCUS ON THE BARTON LIBRARY March 2014 Advertisement the Ricardian Bulletin The magazine of the Richard III Society March 2014 Richard III Society Founded 1924 Contents www.richardiii.net 2 From the Chairman In the belief that many features of the tradi- 3 Reinterment news Annette Carson tional accounts of the character and career of 4 Members’ letters Richard III are neither supported by sufficient evidence nor reasonably tenable, the Society 7 Society news and notices aims to promote in every possible way 12 Future Society events research into the life and times of Richard III, 14 Society reviews and to secure a reassessment of the material relating to this period and of the role in 16 Other news, reviews and events English history of this monarch. 18 Research news Patron 19 Richard III and the men who died in battle Lesley Boatwright, HRH The Duke of Gloucester KG, GCVO Moira Habberjam and Peter Hammond President 22 Looking for Richard – the follow-up Peter Hammond FSA 25 How to rebury a medieval king Alexandra Buckle Vice Presidents 37 The Man Himself: The scoliosis of Richard III Peter Stride, Haseeb John Audsley, Kitty Bristow, Moira Habberjam, Qureshi, Amin Masoumiganjgah and Clare Alexander Carolyn Hammond, Jonathan Hayes, Rob 39 Articles Smith. 39 The Third Plantagenet John Ashdown-Hill Executive Committee 40 William Hobbys Toni Mount Phil Stone (Chairman), Paul Foss, Melanie Hoskin, Gretel Jones, Marian Mitchell, Wendy 42 Not Richard de la Pole Frederick Hepburn Moorhen, Lynda Pidgeon, John Saunders, 44 Pudding Lane Productions Heather Falvey Anne Sutton, Richard Van Allen, 46 Some literary and historical approaches to Richard III with David Wells, Susan Wells, Geoffrey Wheeler, Stephen York references to Hungary Eva Burian 47 A series of remarkable ladies: 7. -

Information Pack 5: Richard III and the Judicial Review, 13Th and 14Th March 2014

Information Pack 5: Richard III and the Judicial Review, 13th and 14th March 2014 During 2013 and 2014 the decision to rebury the remains of Richard III in Leicester Cathedral also faced a legal challenge when the Plantagenet Alliance, a group of Richard’s collateral descendants, pursued a judicial review of the conditions of the exhumation licence awarded to the University of Leicester Archaeological Services, who had excavated the Greyfriars site and who had agreed that Leicester Cathedral would be the appropriate location to reinter the former monarch. The Plantagenet Alliance’s Case On 4th February 2013, six months after the remains had been extracted from the Greyfriars dig site, they were finally confirmed as belonging to Richard III through a DNA match with two female-line descendants of his sister, Anne of York (d. 1476). The discovery sparked national and international interest, and added fuel to the debates about where the former monarch should be buried. The Ministry of Justice, however, was keen to point out that as the University of Leicester Archaeological Services was the legal holder of the exhumation licence, and that therefore as the legal custodian of the remains, the final decision as to where Richard would be reburied lay with them and it seemed that this would take place in Leicester Cathedral, as provisionally agreed. On 26th March 2013, the Plantagenet Alliance therefore announced that it was seeking to challenge the decision to rebury Richard’s remains in Leicester through a judicial review of the exhumation licence issued by the Ministry of Justice to the University of Leicester Archaeological Services. -

Richard III of England from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Richard III of England From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Discovery of remains[edit] Main article: Exhumation and reburial of Richard III of England On 24 August 2012, the University of Leicester and Leicester City Council, in association with the Richard III Society, announced that they had joined forces to begin a search for the remains of King Richard. The search for Richard III was led by Philippa Langley of the Society's Looking For Richard Project with the archaeological work led by University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS).[251][252][253] Experts set out to locate the lost site of the former Greyfriars Church (demolished during Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries), and to discover whether his remains were still interred there.[254][255] By comparing fixed points between maps in a historical sequence, the search located the Church of the Grey Friars, where Richard's body had been hastily buried without pomp in 1485, its foundations identifiable beneath a modern-day city centre car park.[256] Site of Greyfriars Church, Leicester, shown superimposed over a modern map of the area. The skeleton of Richard III was recovered in September 2012 from the centre of the choir, shown by a small blue dot. On 5 September 2012, the excavators announced that they had identified Greyfriars church[257] and two days later that they had identified the location of Robert Herrick's garden, where the memorial to Richard III stood in the early 17th century.[258] A human skeleton was found beneath the Church's choir.[259] Improbably, the excavators found the remains in the first location in which they dug at the car park. -

The Life and Northern Career of Richard III Clara E

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2014 Richard, son of York: the life and northern career of Richard III Clara E. Howell Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Howell, Clara E., "Richard, son of York: the life and northern career of Richard III" (2014). LSU Master's Theses. 2789. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2789 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RICHARD, SON OF YORK: THE LIFE AND NORTHERN CAREER OF RICHARD III A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Clara E. Howell B.A. Louisiana State University, 2011 August 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people to thank for their help and support throughout the process of researching and writing this thesis, as well as through the three years of graduate school. First, I would like to thank my committee in the Department of History. My advisor, Victor Stater, has been a constant source of guidance and support since my days as an undergraduate. It was his undergraduate lectures and assignments that inspired me to continue on to my Masters degree. -

Information Pack 2: Online Petitions and the Richard III Reburial Debate

Information Pack 2: Online Petitions and the Richard III Reburial Debate Following the announcement by the University of Leicester Archaeological Services in September 2012 that the human remains found on the first day of the excavation of the Greyfriars site may well have been those of the lost Richard III, questions were immediately asked about the consequences of such a find. Given the unique nature of the discovery, questions arose as to where, how and according to what religious rites the former monarch should be buried. In the media, journalists and historians voiced the arguments for and against a variety of potential locations for Richard III’s reinterment, and considered the implications of an Anglican or Catholic ceremony. However, online petitions emerged as a vital forum for people across the country and internationally to impart their views on these crucial issues, and even influence the decisions made. What is an E-petition? Online or e-petitions exist in two formats. The first of these are petitions linked directly to the Parliamentary Petitions Committee. These can be created and signed by any British citizen and resident of the United Kingdom, and once their contents have been checked by the Committee to determine their suitability for government consideration, they are made public to be signed. If a parliamentary petition reaches 10,000 signatures, it receives a response from the government, and if it reaches 100,000 signatures the issue concerned is debated in parliament, though in special cases this may occur even before the petition reaches this number. The second category of e-petitions are found in unofficial, third-party websites such as www.change.org and www.avaaz.org. -

Consultations: When and How?

Features Consultations: when and how? It is wise for a public authority to consult before taking a decision that has a significant impact on third parties. Rupert Earle outlines when and Convention (private and family life) does not, of itself, how a public body should perform require consultation, national security was involved, and the challenge was too late. a consultation Rupert Earle At the other extreme, the same judge in R (The Partner The Cabinet Office’s revised Guidance on Consultation Plantagenet Alliance Limited) v The Secretary of T: 020 7551 7609 (July 2012) states ‘there may be a number of State for Justice and University of Leicester (with the [email protected] reasons to consult: to garner views and preferences, Cathedrals of Leicester and York as interested parties) to understand possible unintended consequences (2013) gave the alliance permission to seek a judicial Rupert is recognised as on a policy or to get views on implementation. a ‘star practitioner’ by review of the decision of the Secretary of State to Chambers UK, which Increasing the level of transparency improves the grant, without consultation, a licence for the body of comments that he ‘is quality of policy making by bringing to bear expertise Richard III to be buried in Leicester Cathedral. The universally lauded as and alternative perspectives, and identifying alliance was a campaigning organisation incorporated “a truly excellent lawyer; unintended effects and practical problems. It by the 17th Great-Nephew of Richard III to represent he is consistently should be part of strengthening policy making and the living collateral decedents of Richard III. -

June 2014 Leicester Cathedral – Reinterment of King Richard Iii Report

CABINET – 17 TH JUNE 2014 LEICESTER CATHEDRAL – REINTERMENT OF KING RICHARD III REPORT OF THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE PART A Purpose of Report 1. The purpose of the report is to request approval for the County Council to underwrite in part the early stages of the internal reordering of Leicester Cathedral (internal building works) in preparation for the reinterment of Richard III in spring 2015. Recommendations 2. It is recommended that: (a) the County Council provides funding of £250,000 to assist with the underwriting of costs to be incurred by Leicester Cathedral in commissioning the first stages of the internal reordering of the Cathedral in preparation for the reinterment of King Richard III; (b) it be noted that the Leicester City Mayor has indicated that the City Council will be making a similar contribution to the underwriting and that the Cathedral’s major fund-raising in regard to the reordering of the Cathedral will be launched later in June 2014. Reasons for Recommendations 3. Leicester Cathedral has already raised a significant sum to assist with the underwriting but that sum is not sufficient to allow for the early commissioning of contracts for the reordering and therefore the City and County Councils have been asked if they could assist in the underwriting. Timetable for Decisions (including Scrutiny) 4. An early decision is required in recognition of the timescale set out above. Policy Framework and Previous Decisions 5. The Cabinet at its meeting on 13 th September 2013 approved a contribution of £250,000 towards the development of Leicester Cathedral Gardens, recognising that the Diocese covers the City and County and the anticipated reinterment of Richard III in the Cathedral. -

Plantagenet Alliance

Neutral Citation Number: [2014] EWHC 1662 Case No: CO/5313/2013 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN’S BENCH DIVISION DIVISIONAL COURT Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 23/05/2014 Before: LADY JUSTICE HALLETT Vice President of the Queen’s Bench Division MR JUSTICE OUSELEY MR JUSTICE HADDON-CAVE - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between: THE QUEEN (on the application of Claimant PLANTAGENET ALLIANCE LTD) - and - SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE First Defendant - and - THE UNIVERSITY OF LEICESTER Second Defendant - and - LEICESTER CITY COUNCIL Third Defendant THE MEMBERS FOR THE TIME BEING OF First Interested THE CHAPTER, THE COUNCIL AND THE Party COLLEGE OF CANONS OF THE CATHEDRAL OF SAINT MARTIN LEICESTER THE MEMBERS FOR THE TIME BEING OF Second Interested THE CHAPTER, THE COUNCIL AND THE Party COLLEGE OF CANONS OF THE CATHEDRAL AND METROPOLITICAL CHURCH OF SAINT PETER YORK - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Gerard Clarke and Tom Cleaver (instructed by Gordons LLP) for the Claimant James Eadie QC and Ben Watson (instructed by The Treasury Solicitor) for the First Defendant Anya Proops and Heather Emmerson (instructed by The University of Leicester) for the Second Defendant Andrew Sharland (instructed by Leicester City Council) for the Third Defendant. Hearing dates: 13th and 14th March 2014 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. Plantagenet Alliance Ltd -v- The Secretary of State for Justice & Others This is the Judgment of the Court: INTRODUCTION 1. Richard III was the last King of England to die on the battlefield. His death marked the end of the Middle Ages. He has remained a significant and controversial historical figure ever since. -

The Corpse, Heritage, and Tourism: the Multiple Ontologies of the Body of King Richard III of England

The corpse, heritage, and tourism: The multiple ontologies of the body of King Richard III of England Craig Young and Duncan Light This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge in Heritage of Death: Landscapes of Emotion, Memory and Practice (ISBN: 9781138217515). https://www.routledge.com/Heritage-of-Death-Landscapes-of- Emotion-Memory-and-Practice/Frihammar-Silverman/p/book/9781138217515 This work should be cited as: Young, C. and Light, D. (2018) The corpse, heritage, and tourism: The multiple ontologies of the body of King Richard III of England, in Frihammer, M. and Silverman, H. (eds.) Heritage of Death: Landscapes of Emotion, Memory and Practice, Routledge, Abingdon, 92-104 Introduction In August 2012 the bodily remains of King Richard III of England (b.1452-d.1485) were found under a car park in the English city of Leicester. Richard III was killed during the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, but beyond historical records suggesting that his body was taken from there to somewhere near Greyfriars Church in Leicester, the exact location of his remains was unknown and not marked by any grave. The remarkable rediscovery of his body could be considered in many ways, but in this chapter we are concerned with exploring the centrality of the materiality of these human remains for a range of interlocking social processes, including national identity, historical narrative, memory, inter-urban competition in the context of global neoliberalism, and heritage tourism. Prior to the discovery of the body itself Richard III had for long been the subject of competing interpretations and claims. -

Approved Judgment

Neutral Citation Number: 2013 EWHC 3164 (Admin) Case No: 5313/2013 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION ADMINISTRATIVE COURT Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 18/10/2013 Before: MR JUSTICE HADDON-CAVE - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between: (on the application of THE PLANTAGENET Claimant ALLIANCE LIMITED) - and - SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE First Defendant - and - THE UNIVERSITY OF LEICESTER Second - and - Defendant THE MEMBERS FOR THE TIME BEING OF THE CHAPTER, THE COUNCIL AND THE COLLEGE First Interested OF CANONS OF THE CATHEDRAL OF SAINT Party MARTIN LEICESTER - and - THE MEMBERS FOR THE TIME BEING OF THE Second CHAPTER, THE COUNCIL AND THE COLLEGE Interested OF CANONS OF THE CATHEDRAL AND Party METROPOLITAN CHURCH OF SAINT PETER YORK - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Gerard Clarke and Tom Cleaver (instructed by Gordons LLP) for the Claimant Tom Weisselberg (instructed by The Treasury Solicitor) for the First Defendant Anya Proops and Heather Emmerson (instructed by University of Leicester) for the Second Defendant Hearing date: 26th September 2013 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. R (oao the Plantagenet Alliance) v SSJ and Leicester University MR JUSTICE HADDON-CAVE: INTRODUCTION 1. On 15th August 2013, I granted Permission for Judicial Review in this matter on the papers and made certain orders and directions, including a Protective Costs Order (“PCO”) and an order for Disclosure. The substantive hearing has now been set down for hearing before the Divisional Court on 26th November 2013. 2. On 26th September 2013, a hearing took place before me in the vacation in Court 3 at the Royal Courts of Justice.