INFANTRY in BATTLE from Somalia to the Global War on Terror

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BALKANS Briefing

BALKANS Briefing Skopje/Brussels, 27 July 2001 MACEDONIA: STILL SLIDING This ICG briefing paper continues the analysis of the Macedonian crisis begun in the ICG’s two most recent reports from Skopje: Balkans Reports No. 109, The Macedonian Question: Reform or Rebellion (5 April 2001) and No. 113, Macedonia: The Last Chance for Peace (20 June 2001). It analyses what has happened during the past five weeks, anticipates what may happen next, and describes the dilemma the international community faces if it is to improve the prospects of averting an open ethnic war. I. OVERVIEW almost nothing else separates the two sides, who have agreed on “95 per cent of those things that were to be negotiated”.1 Despite the ceasefire announced on 26 July 2001, and the promised resumption of political talks in Yet this is not how the matter appears inside the Tetovo on 27 July, Macedonia is still locked in country. Ethnic Macedonians believe the republic- crisis and threatened by war. Neither ethnic wide use of Albanian – as proposed by the Macedonian nor ethnic Albanian leaders have been international mediators – would pose a threat to converted to belief in a ‘civic’ settlement that their national identity that cannot be justified, would strengthen democracy by improving given that only one third to one quarter of the minority conditions, without weakening the population speaks the language. They are also integrity of the state. Ethnic Macedonians fear that convinced that all Albanians would refuse to civic reforms will transform the country communicate in Macedonian. Given that almost no exclusively to its, and their, detriment, while ethnic ethnic Macedonians can speak Albanian, they also Albanians are sceptical that any reforms can really fear that bilingualism would become necessary for be made to work in their favour. -

To Read Article As

He can see through walls, His Helmet is video-connected, and His rifle Has computer precision. We cHeck out tHe science (and explosive poWer) beHind tHe technology tHat’s making tHe future of the military into Halo come to life. by StinSon Carter illustration by kai lim want the soldier to think of himself as the $6 battalions. Today we fight with Small Tactical Units. Million Man,” says Colonel Douglas Tamilio, And the heart of the Small Tactical Unit is the single project manager of Soldier Weapons for the U.S. dismounted soldier. Army. In case you haven’t heard, the future of In Afghanistan, as in the combat zones of the fore warfare belongs to the soldier. The Civil War was fought seeable future, we will fight against highly mobile, by armies. World War II was fought by divisions. Viet highly adaptive enemies that blend seamlessly into nam was fought by platoons. Operation Desert Storm their environments, whether that’s a boulderstrewn was fought by brigades and the second Iraq war by mountainside or the densely populated urban jungle. enhanced coMbaT heLMeT Made from advanced plastics rather than Kevlar, the new ECH offers 35 percent more protection GeneraTion ii than current helmets. heLMeT SenSor The Gen II HS provides the wearer with analysis of explosions and any neTT Warrior other potential source This system is designed to provide of head trauma. vastly increased situational awareness on the battlefield, allowing combat leaders to track the locations and health ModuLar of their teams, who are viewing tactical LiGhTWeiGhT information via helmet-mounted Load-carryinG computer screens. -

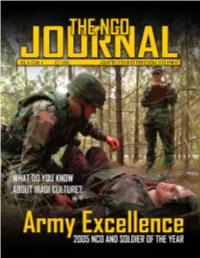

NCO Journal October 05.Pmd

VOL: 14, ISSUE: 4 OCT 2005 A QUARTERLY FORUM FOR PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT Soldiers in a Humvee search for people wishing to be rescued from Hurricane Katrina floodwaters in downtown New Orleans. Photo courtesy of www.army.mil. by Staff Sgt. Jacob N. Bailey INSIDE“ ON POINT 2-3 SMA COMMENTS IRAQI CULTURE: PRICELESS Tell the Army story with pride. They say “When in Rome, do 4-7 NEWS U CAN USE as the Romans.” But what do you know about Iraqi culture? The Army is doing its best to LEADERSHIP ensure Soldiers know how to “ manuever as better ambassa- dors in Iraq. DIVORCE: DOMESTIC ENEMY Staff Sgt. Krishna M. Gamble 18-23 National media has covered it, researchers have studied it and the sad fact is Soldiers are ON THE COVER: living it. What can you as Spc. Eric an NCO do to help? Przybylski, U.S. Dave Crozier 8-11 Army Pacific Command Soldier of the Year, evaluates NCO AND SOLDIER OF THE YEAR a casualty while he Each year the Army’s best himself is evaluated NCOs and Soldiers gather to during the 2005 NCO compete for the title. Find out and Soldier of the who the competitors are and Year competition more about the event that held at Fort Lee, Va. PHOTO BY: Dave Crozier embodies the Warrior Ethos. Sgt. Maj. Lisa Hunter 12-17 TRAINING“ ALIBIS NCO NET 24-27 LETTERS It’s not a hammer, but it can Is Detriot a terrorist haven? Is Bart fit perfectly in a leader’s Simpson a PsyOps operative? What’s toolbox. -

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order Online

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order online Table of Contents Acknowledgments Introduction Glossary 1. Executive Summary The 1999 Offensive The Chain of Command The War Crimes Tribunal Abuses by the KLA Role of the International Community 2. Background Introduction Brief History of the Kosovo Conflict Kosovo in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Kosovo in the 1990s The 1998 Armed Conflict Conclusion 3. Forces of the Conflict Forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Yugoslav Army Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs Paramilitaries Chain of Command and Superior Responsibility Stucture and Strategy of the KLA Appendix: Post-War Promotions of Serbian Police and Yugoslav Army Members 4. march–june 1999: An Overview The Geography of Abuses The Killings Death Toll,the Missing and Body Removal Targeted Killings Rape and Sexual Assault Forced Expulsions Arbitrary Arrests and Detentions Destruction of Civilian Property and Mosques Contamination of Water Wells Robbery and Extortion Detentions and Compulsory Labor 1 Human Shields Landmines 5. Drenica Region Izbica Rezala Poklek Staro Cikatovo The April 30 Offensive Vrbovac Stutica Baks The Cirez Mosque The Shavarina Mine Detention and Interrogation in Glogovac Detention and Compusory Labor Glogovac Town Killing of Civilians Detention and Abuse Forced Expulsion 6. Djakovica Municipality Djakovica City Phase One—March 24 to April 2 Phase Two—March 7 to March 13 The Withdrawal Meja Motives: Five Policeman Killed Perpetrators Korenica 7. Istok Municipality Dubrava Prison The Prison The NATO Bombing The Massacre The Exhumations Perpetrators 8. Lipljan Municipality Slovinje Perpetrators 9. Orahovac Municipality Pusto Selo 10. Pec Municipality Pec City The “Cleansing” Looting and Burning A Final Killing Rape Cuska Background The Killings The Attacks in Pavljan and Zahac The Perpetrators Ljubenic 11. -

Soldier Armed Body Armor Update by Scott R

Soldier Armed Body Armor Update By Scott R. Gourley In a June 2006 statement before the dier Survivability with the Office of House Armed Services Committee, Program Executive Office Soldier, the mong the most significant recent then-Maj. Gen. Stephen M. Speakes, latest system improvements inte- Adevelopments that directly in- who was director, Force Development, grated into the new improved outer crease warfighter safety and effective- Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff, G-8, tactical vest, as with earlier advances, ness are the enhancements to the pro- offered a brief chronology of the IBA reflect additional feedback from sol- tective ensemble known as Interceptor program, which highlighted the link- diers in the field. body armor (IBA). As the most up-to- age between that program’s evolution “We receive that feedback in differ- date body armor available, IBA is a and warfighter feedback. ent ways,” Myles explained. “One way, modular body armor system that con- I 1999—The Army started fielding for example, was through a soldier pro- sists of an outer vest, ballistic plates the OTV with small arms protective tection demonstration that we con- and attachments that increase the areas inserts (SAPI) to soldiers deployed in ducted in August 2006 at Fort Benning, of coverage. The system increases sol- Bosnia. Ga. We had industry provide us some dier survivability by stopping or slow- I April 2004—Theater reported 100 body armor for soldiers to evaluate. ing bullets and fragments and reducing percent fill of 201,000 sets of IBA (OTV These were soldiers that had just re- the number and severity of wounds. -

The History of the Macedonian Textile

OCCASIONAL PAPER N. 8 TTHHEE HHIISSTTOORRYY OOFF TTHHEE MMAACCEEDDOONNIIAANN TTEEXXTTIILLEE IINNDDUUSSTTRRYY WWIITTHH AA FFOOCCUUSS OONN SSHHTTIIPP Date: November 29th, 2005 Place: Skopje, Macedonia Introduction- the Early Beginnings and Developments Until 1945 The growth of the Macedonian textile sector underwent diverse historical and economic phases. This industry is among the oldest on the territory of Macedonia, and passed through all the stages of development. At the end of the 19th century, Macedonia was a territory with numerous small towns with a developed trade, especially in craftsmanship (zanaetchistvo). The majority of the population lived in rural areas, Macedonia characterized as an agricultural country, where most of the inhabitants satisfied their needs through own production of food. The introduction and the further development of the textile industry in Macedonia were mainly induced by the needs of the Ottoman army for various kinds of clothing and uniforms. Another reason for the emerging of the textile sector was to satisfy the needs of the citizens in the urban areas. An important factor for the advancement of this industry at that time was the developed farming, cattle breeding in particular. (stocharstvo). The first textile enterprises were established in the 1880‟s in the villages in the region of Bitola – Dihovo, Magarevo, Trnovo, and their main activity was production of woolen products. Only a small number of cotton products were produced in (zanaetciski) craftsmen workshops. The growth of textiles in this region was natural as Bitola, at that time also known as Manastir, was an important economic and cultural center in the European part of Turkey.[i] At that time the owners and managers of the textile industry were businessmen with sufficient capital to invest their money in industrial production. -

English and INTRODACTION

CHANGES AND CONTINUITY IN EVERYDAY LIFE IN ALBANIA, BULGARIA AND MACEDONIA 1945-2000 UNDERSTANDING A SHARED PAST LEARNING FOR THE FUTURE 1 This Teacher Resource Book has been published in the framework of the Stability Pact for South East Europe CONTENTS with financial support from the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It is available in Albanian, Bulgarian, English and INTRODACTION..............................................3 Macedonian language. POLITICAL LIFE...........................................17 CONSTITUTION.....................................................20 Title: Changes and Continuity in everyday life in Albania, ELECTIONS...........................................................39 Bulgaria and Macedonia POLITICAL PERSONS..............................................50 HUMAN RIGHTS....................................................65 Author’s team: Terms.................................................................91 ALBANIA: Chronology........................................................92 Adrian Papajani, Fatmiroshe Xhemali (coordinators), Agron Nishku, Bedri Kola, Liljana Guga, Marie Brozi. Biographies........................................................96 BULGARIA: Bibliography.......................................................98 Rumyana Kusheva, Milena Platnikova (coordinators), Teaching approches..........................................101 Bistra Stoimenova, Tatyana Tzvetkova,Violeta Stoycheva. ECONOMIC LIFE........................................103 MACEDONIA: CHANGES IN PROPERTY.......................................104 -

LAP KUMANOVO, All Municipalities

Local action plan ‐ Kumanovo Responsible Necessary resources institution Time frame (short‐term 0‐ 6m, mid‐term (municipality, (municipal budget, Strategy/Law/Plan/Progra 6m‐2y, long‐ government, national budget, Targets Specific targets m Actions term 2y‐5y)PHC,PCE etc.) donations) Indicators to track Target 1. Increased access to Strategic Framework for Development of mid‐term (6m‐ municipality, CPH municipal budget Developed program passed Strengthening drinking water from Health and Environment Program for priority 2y) Kumanovo by the municipal council public policy in 93.4% to 100% and (2015‐2020), Strategy for geographical areas to (planned adoption at the the municipality hygienic sanitation water (Official Gazette improve access to end of 2017) to improve 122/12), Law on Waters, water and sanitation access to water Law on Local Self‐ with the dynamics of and sanitation Government activities Increasing public funding Strategic Framework for Decision on the mid‐term (1 municipality municipal budget Decision published in the from the municipal Health and Environment amount of funds year) Official Gazette of the budget intended to (2015‐2020), Strategy on annually in the Municipality of Kumanovo improve access to water Waters (Official Gazette municipality intended and sanitation 122/12), Law on Local Self‐ to improve access to Government water and sanitation Target 2. Raising public awareness Action Plan on Campaigns short‐term (0‐6 Public Health municipal budget, Number of held Reducing on the impact of the Environment and Health -

Mission Essential Harvest

MISSION ESSENTIAL HARVEST Islam Yusufi (Presented at Szeged Roundtable on Small Arms, 14-15 September 2001, Szeged, Hungary) Operation Essential Harvest is consisted of collection of weapons and ammunition from so called NLA voluntarily handed in to NATO's forces, named as a Task Force Harvest. The other tasks include, transportation and disposal of weapons which are surrendered; and, Transportation and destruction of ammunition that is turned in as a part of broader process giving an end to the conflict in Macedonia. Evolution ATO Secretary General on 14 June 2001 received a letter from the President of the NNRepublic of Macedonia, requesting NATO’s assistance in the implementation of the Plan and Program for overcoming the crisis in Macedonia. NATO responded to the President’s request and produced a draft plan for the collection of weapons from the armed insurgents, named Operation "ESSENTIAL HARVEST". The North Atlantic Council approved the plan on 29 June 2001 and NATO’s Secretary General was able to submit an early proposal to the President of Macedonia for weapons collection. At that time NATO and the President agreed to a set of four pre-conditions to be met for the 30- day mission to take place: 1. a political agreement signed by the main Parliamentary leaders; 2. a status of forces agreement (SOFA) with the Republic of Macedonia and agreed conditions for the Task Force; 3. an agreed plan for weapons collection, including an explicit agreement by the ethnic Albanian armed groups to disarm; and 4. an enduring cease-fire. Framework Agreement, concluded in Ohrid and signed in Skopje on 13 August 2001, by the four leaders of political parties, members of broader coalition, in its introduction under the title Cessation of Hostilities, stipulates the following: "The parties underline the importance of the commitments of July 5, 2001. -

The Lessons of the Iraq War: Issues Relating to Grand Strategy

CSIS___________________________________ Center for Strategic and International Studies 1800 K Street N.W. Washington, DC 20006 (202) 775-3270 (To comment: [email protected] For Updates see Executive Summary: http://www.csis.org/features/iraq_instantlessons_exec.pdf; Main Report: http://www.csis.org/features/iraq_instantlessons.pdf) The Lessons of the Iraq War: Issues Relating to Grand Strategy Asymmetric Warfare, Intelligence, Weapons of Mass Destruction, Conflict Termination, Nation Building and the “New Middle East” Anthony H. Cordesman Arleigh A. Burke Chair for Strategy July 3, 2003 Copyright Anthony H. Cordesman, All Rights Reserved. No quotation or reproduction Cordesman: The Lessons of the Iraq War 7/3/03 Page 2 Acknowledgments The author would like to thank Brian Hartman and Julia Powell of ABC for help in the research for this book, and Brian Hartman for many of the numbers on the size of the Coalition air effort, and Coalition Forces. Ryan Faith helped with the research for the chronology of events and both Ryan Faith and Jennifer Moravitz helped with the organization and editing. The reader should also be aware that this book makes extensive use of reporting on the war from a wide range of press sources, only some of which can be fully footnoted, interviews with serving and retired officers involved in various aspects of the planning and execution of the war, and the extensive work done by Australian, British, and US officers in preparing daily briefings and official background materials on the conflict. Copyright Anthony H. Cordesman, All Rights Reserved. No quotation or reproduction without the express written permission of the author. -

Business Leaders in Action Results for America

Business Executives for National Security Business Leaders in Action LEADERSHIP REPORT 2009 Results for America Business Executives for National Security Business Leaders in Action Results for America Leadership Report 2009 Printed March 2009 1 Joseph E. Robert, Jr., Chairman Bringing business models to our nation’s security To Our Members: www.bens.org Upon assuming the Chairmanship of BENS nearly two years ago, I • laid out an over-arching goal of expanding our reach – deploying the unique skills and perspectives of business executives to tackle new national security challenges while continuing to address issues where we already have a reputation for making positive change. f 202-296-2490 • This report, the first of its kind, summarizes BENS’ work over the past year, from advo- cating smart spending at the Pentagon to innovative disaster response solutions. We are also partnering with others to bring the BENS methodology to address significant chal- lenges such as cyber security and energy. Regardless of where BENS is involved, one thing is clear: There has never been a more opportune time for business executives to p 202-296-2125 help improve America’s security. • Keeping the momentum of our current initiatives while expanding our reach naturally requires resources. I’m proud to note that despite the economy’s difficulties last year, BENS made a strong financial finish in 2008. But as we all know, the economy is still very fragile and likely to pose even greater challenges in 2009. Nevertheless, I’m con- fident that with your involvement and support, BENS will grow and continue to make Washington, DC 20006 significant contributions to our nation’s security. -

The Perception Versus the Iraq War Military Involvement in Sean M. Maloney, Ph.D

Are We Really Just: Peacekeepers? The Perception Versus the Reality of Canadian Military Involvement in the Iraq War Sean M. Maloney, Ph.D. IRPP Working Paper Series no. 2003-02 1470 Peel Suite 200 Montréal Québec H3A 1T1 514.985.2461 514.985.2559 fax www.irpp.org 1 Are We Really Just Peacekeepers? The Perception Versus the Reality of Canadian Military Involvement in the Iraq War Sean M. Maloney, Ph.D. Part of the IRPP research program on National Security and Military Interoperability Dr. Sean M. Maloney is the Strategic Studies Advisor to the Canadian Defence Academy and teaches in the War Studies Program at the Royal Military College. He served in Germany as the historian for the Canadian Army’s NATO forces and is the author of several books, including War Without Battles: Canada’s NATO Brigade in Germany 1951-1993; the controversial Canada and UN Peacekeeping: Cold War by Other Means 1945-1970; and the forthcoming Operation KINETIC: The Canadians in Kosovo 1999-2000. Dr. Maloney has conducted extensive field research on Canadian and coalition military operations throughout the Balkans, the Middle East and Southwest Asia. Abstract The Chrétien government decided that Canada would not participate in Operation Iraqi Freedom, despite the fac ts that Canada had substantial national security interests in the removal of the Saddam Hussein regime and Canadian military resources had been deployed throughout the 1990s to contain it. Several arguments have been raised to justify that decision. First, Canada is a peacekeeping nation and doesn’t fight wars. Second, Canada was about to commit military forces to what the government called a “UN peacekeeping mission” in Kabul, Afghanistan, implying there were not enough military forces to do both, so a choice had to be made between “warfighting” and “peacekeeping.” Third, the Canadian Forces is not equipped to fight a war.