Chapter 6: Transportation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I-89 Commuter Transit Service Study FINAL REPORT April 2017

I-89 Commuter Transit Service Feasibility Study FINAL REPORT Upper Valley Lake Sunapee Regional Planning Commission April 2017 I-89 Commuter Transit Service Feasibility Study AECOM Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Goals and Objectives ................................................................................................................................... 1 3. Previous Studies .......................................................................................................................................... 1 4. Existing Transit Services .............................................................................................................................. 3 4.1 Local Bus Transit ............................................................................................................................... 3 4.2 Commuter Bus Transit ....................................................................................................................... 5 4.3 Intercity Transit .................................................................................................................................. 6 4.4 Rideshare Services ........................................................................................................................... 6 4.5 Park-and-Ride Lots ........................................................................................................................... -

Public Involvement Report – December 2014

New Hampshire Capitol Corridor Rail & Transit Alternatives Analysis (Parts A & B) Task 1: Public Involvement Report – December 2014 New Hampshire Capitol Corridor Rail & Transit Alternatives Analysis (Parts A & B) Task 1: Public Involvement Report – December 2014 Table of Contents 1 Project Purpose and Need Summary .................................................................................................... 1 2 Task Objectives ..................................................................................................................................... 1 3 Agency and Stakeholder Coordination ................................................................................................. 2 3.1 Project Advisory Committee (PAC) ............................................................................................... 2 3.2 Other Stakeholders ....................................................................................................................... 3 3.3 Public Involvement........................................................................................................................ 6 3.4 Website ......................................................................................................................................... 9 3.5 Media Outreach .......................................................................................................................... 10 3.6 Project Electronic Mailing List .................................................................................................... -

Public Transportation Needs in New Hampshire

A snapshot of how public transportation is funded and structured throughout the state. MOBILITY NEEDS in THE STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE Introduction Public transit is a lifeline to many New Hampshire residents of all ages and demographics. In FTA Mandated ADA Service ADA Paratransit Cost Growth order to maintain the public transit services available in New Hampshire today, signicant Transit agencies throughout the state have been facing Cooperative Alliance for Seacoast Transportation (COAST) increases in public funding are critically needed. The federal funding that New Hampshire’s an increasing need for federally mandated Americans public transit systems rely heavily upon is not keeping pace with the growing demand and with Disabilities Act (ADA) service, especially for dialysis rising service costs. With adequate ongoing support, transit agencies can focus on providing trips. This on-demand service is for people with disabili- reliable transportation service to the region and ensure access for NH’s future generations. ties that keep them from riding the regular xed route bus. COAST, the public transit agency serving the New Hampshire Seacoast, has seen demand for mandated ADA services grow 880% from 2008-2018, and their cost to provide those services increase 744%. Federal alloca- tions of transit funds have not risen accordingly, leaving public transit agencies to bear the burden of these costs. Economic Development & Land Use In order for economic development to continue to thrive in NH, businesses need to be able to oer public transit to potential employees. Employment sites with transit access can leverage this to attract additional workers and address parking needs. -

Final 2012 Coordinated Public Transit & Human Services Transportation

Coordinated Public Transit & Human Services Transportation Plan for Southeast NH Region Approved by Strafford Regional Planning Commission on 3/16/12 Celebration of the Startup of the North Bus Service in Wakefield, NH Prepared by Rockingham Planning Commission 156 Water Street Exeter, NH 03833 (603)778-0885 Strafford Regional Planning Commission 150 Wakefield Street, Suite 12 Rochester, NH 03867 (603) 004-3500 This report was funded in part through grant(s) from the Federal Highway Administration and the Federal Transit Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. The views and opinions of the agencies expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the U. S. Department of Transportation. COORDINATED PUBLIC TRANSIT & HUMAN SERVICES TRANSPORTATION PLAN SOUTHEAST NH REGION 2012 UPDATE TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 OVERVIEW/BACKGROUND .................................................................................................. 1-1 1.1 Introduction/Purpose ............................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Plan Structure .......................................................................................................................... 1-2 2.0 STATE AND FEDERAL TRANSPORTATION INITIATIVES .......................................... 2-1 2.1 Statewide Coordination Plan ................................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Citizens Advisory Committee & New Hampshire Long Range Transportation Plan ............ -

Funding Transportation in Vermont

Rockefeller Center at Dartmouth College Policy Research Shop The Center for Public Policy and the Social Sciences Funding Transportation in Vermont An Assessment of Applicable Funding Options PRS Policy Brief 0809-04 May 12, 2009 Prepared by: Christine Souffrant Alexandra Mahler-Haug This report was written by undergraduate students at Dartmouth College under the direction of professors in the Rockefeller Center. Support for the Policy Research Shop is provided by the Ford Foundation. Contact: Nelson A. Rockefeller Center, 6082 Rockefeller Hall, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 03755 http://rockefeller.dartmouth.edu/shop/ • Email: [email protected] Rockefeller Center at Dartmouth College Policy Research Shop The Center for Public Policy and the Social Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION 3 I. CURRENT VERMONT PROGRAMS 4 1.1 AT Advanced Transit (Fare Free System: Revenue through contribution and Government Support) 1.2 Addison County Transit (limited fare system: revenue through Contracts) 4 1.3 Chittenden County Transportation Authority (Typical Fare System) 5 1.4 Funding Challenges of Vermont 5 II. CURRENT PROGRAMS IN OTHER STATES 7 2.1 Manchester Transit Authority: School funding contract) 7 2.2 Concord Area Transit (CAT): Funding due to community economic demographics 7 2.3 Cooperative Alliance for Seacoast Transportation (COAST): Funding without State Aid 8 III.COMPARISON & EVALUATIONS OF PROBABLE PROGRAMS FOR VT 8 3.1. Connections between Services & Funding of New England Area 8 3.2 The Use of Institutions for Funding 10 3.3 The Use of Demographics; An advantage for Funding 12 3.4 Funding without the State 12 3.5 2009 Federal Stimulus Package 12 CONCLUSION 13 REFERENCES 15 Rockefeller Center at Dartmouth College Policy Research Shop The Center for Public Policy and the Social Sciences EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Due to the lack of cohesion amongst Vermont’s local transportation systems, coordination is an endeavor that is currently being considered. -

Public Transportation in Vermont

Rockefeller Center at Dartmouth College Policy Research Shop The Center for Public Policy and the Social Sciences Public Transportation in Vermont An Assessment of Applicable Methods of Improvement and Funding for Vermont Transportation PRS Policy Brief 0809-03 March 1, 2009 Prepared by: Kahlie Dufresne Chase R. Raines Christine Souffrant Tara K. Wohlgemuth This report was written by undergraduate students at Dartmouth College under the direction of professors in the Rockefeller Center. Support for the Policy Research Shop is provided by the Ford Foundation. Contact: Nelson A. Rockefeller Center, 6082 Rockefeller Hall, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 03755 http://rockefeller.dartmouth.edu/shop/ • Email: [email protected] Rockefeller Center at Dartmouth College Policy Research Shop The Center for Public Policy and the Social Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1. INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION VARIES THROUGHOUT VERMONT 4 1.2 VERMONT: A PREDOMINANTLY RURAL STATE/ISSUE FOR TRANSPORTATION 4 1.3 ISSUE WITH COORDINATING VT TRANSPORTATION AND FUNDING METHODS 2. THE CURRENT STATE OF PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION IN VERMONT 5 2.1 PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION VARIES THROUGHOUT VERMONT 5 2.2 LOCAL PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION AGENCIES 7 2.2.1 Addison County Transit Resources 7 2.2.2 Advance Transit Inc. 8 2.2.3 Chittenden County Transportation Authority 8 2.3 FUNDING OF VERMONT’S LOCAL PUBLIC TRANSIT SYSTEMS 9 2.3.1 Fare free systems: Advanced Transit 10 2.3.2 Limited fare systems: Addison Country Transit Resources 10 2.3.3 Typical fare systems: Chittenden Country Transportation Authority 10 2.4 INTERSTATE AND LONG-DISTANCE PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION OPTIONS 11 2.4.1 Greyhound Line 11 2.4.2 Rail 11 2.4 GO VERMONT 122 2.4.1 Carpooling 12 2.4.2 Vanpooling 12 2.4.3 Park-and-Ride 13 2.5 ANALYSIS OF CURRENT PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION SERVICE IN VERMONT 13 2.5.1 Funding Challenges of Vermont 14 3. -

Coordinated Public Transit/Human Services Transportation Plan Contents Ii

Coordinated Public Transit/ Human Services Transportation Plan for the Greater Derry-Salem Region Prepared By: Rockingham Planning Commission 156 Water Street Exeter, N.H. 03833 (603) 778-0885 Southern NH Planning Commission 438 Dubuque St, Manchester, N.H. 03102 (603) 669-4664 July 2016 This report was funded in part through grant[s] from the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. The views and opinions of the agencies expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the U. S. Department of Transportation. This Page Intentionally Left Blank i Coordinated Public Transit & Human Service Transportation Plan Greater Derry-Salem Region 2016 Update TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1. Introduction ......................................................................................... 1-1 Project Background ............................................................................................ 1-1 Planning Process ............................................................................................... 1-2 Chapter 2. Transit Dependent Populations & Service Need .............................. 2-1 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 2-1 Population & Age .............................................................................................. 2-1 Auto Availability ............................................................................................... 2-5 Income ............................................................................................................... -

Service Development Plan – November 2014 Table of Contents 1 Project Purpose and Need Summary

New Hampshire Capitol Corridor Rail & Transit Alternatives Analysis (Parts A & B) Task 9: Service Development Plan – November 2014 Table of Contents 1 Project Purpose and Need Summary .................................................................................................... 1 2 Task Objectives ..................................................................................................................................... 1 3 SDP Report Organization....................................................................................................................... 2 4 Rationale, Goals, and Objectives .......................................................................................................... 3 4.1 Public Concern/Project Need ........................................................................................................ 3 4.1.1 Study Corridor Dynamics ...................................................................................................... 4 4.1.2 Project History and Planning Context................................................................................... 4 4.1.3 Population and Employment ................................................................................................ 6 4.1.4 Existing and Future Land Use ............................................................................................... 8 4.1.5 Economic Development and Land Use ................................................................................. 9 4.1.6 Project Need Summary ...................................................................................................... -

Rural Public Transportation and Maine: Review of State Best Practices

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Transportation Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center 6-2021 Rural Public Transportation and Maine: Review of State Best Practices Erin Brown Jonathan Rubin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mcspc_transport This Report is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transportation by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rural Public Transportation and Maine: Review of State Best Practices Rural Public Transportation and Maine: Review of State Best Practices Technical Report June 2021 Erin Brown and Jonathan Rubin Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center and the School of Economics University of Maine Abstract MaineDOT has a family of transit plans that have been developed over the past five years through collaborative efforts with partners and stakeholders. These plans share similar themes, guidance, and recommendations and tie into the Department’s last Strategic Plan, which was completed in 2016. However, since their development, there have been a number of important and related efforts and developments that impact the strategic vision and plan for transit services in Maine. This report reviews how other states with similar demographics, population disbursements, and climates are addressing their transit challenges, with a focus on rural areas, access, and equity. One caution is that states and transit agencies do not use the same metrics when reporting program costs and benefits. Acknowledgements and Disclaimers This study would not have been possible without the strong cooperation of the Maine Department of Transportation. -

Statewide Strategic Transit Assessment

Statewide Strategic Transit Assessment with RSG, Inc. McFarland Johnson Schweiger Consulting, LLC January 31, 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Strategic Statewide Transit Assessment (SSTA) is intended to be a guide toward a sustainable future for public transit in New Hampshire. Through more than a dozen separate tasks, the study team, led by Steadman Hill Consulting, Inc., worked with NHDOT’s Bureau of Rail and Transit to take a comprehensive look at bus transportation in the state and consider ways that it could better meet the needs of New Hampshire residents. The study was cognizant of the role of demand response transportation and rail as well, but these modes were not the focus of the effort. Policy Until now, NHDOT has not had any official, explicit policy regarding public transit. In consultation with the stakeholders committee for the SSTA, the transit providers and the regional planning commissions, as well as taking public input into account, the following policies for operations and capital spending were developed. These are listed in descending order of priority. Operations • Basic mobility for transit-dependent people • Access to employment for transit-dependent people • Maximizing ridership and efficiency • Supporting economic vitality • Attracting millennials/choice riders Capital • Transit fleets must be in a state of good repair • Passenger facilities are an essential part of the public transportation system • Safe pedestrian access to and from bus stops is essential • Maximize use of technology While basic mobility should continue to be the primary goal of public transportation in the state, for future funding over and above the spending levels for currently-provided service, the amount of non-intercity 5311 funding spent on basic mobility should be reduced from 40% of the total to 33% of the total, with additional funds allocated to other policy goals, especially: • Access to jobs; • Maximizing ridership; and • Supporting economic vitality. -

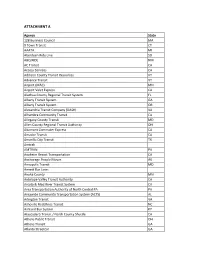

Attachment A

ATTACHMENT A Agency State 128 Business Council MA 9 Town Transit CT AAATA MI Aberdeen Ride Line SD ABQ RIDE NM AC Transit CA Access Services CA Addison County Transit Resources VT Advance Transit VT Airport (MAC) MN Airport Valet Express CA Alachua County Regional Transit System FL Albany Transit System GA Albany Transit System OR Alexandria Transit Company (DASH) VA Alhambra Community Transit CA Allegany County Transit MD Allen County Regional Transit Authority OH Altamont Commuter Express CA Amador Transit CA Amarillo City Transit TX Amtrak AMTRAN PA Anaheim Resort Transportation CA Anchorage People Mover AK Annapolis Transit MD Annett Bus Lines Anoka County MN Antelope Valley Transit Authority CA Arcata & Mad River Transit System CA Area Transportation Authority of North Central PA PA Areawide Community Transportation System (ACTS) AL Arlington Transit VA Asheville Redefines Transit NC Ashland Bus System KY Atascadero Transit / North County Shuttle CA Athens Public Transit OH Athens Transit GA Atlanta Streetcar GA Atlantic Station Shuttle GA Atomic City Transit NM Auburn Transit (Placer County Department of Public Works) CA Augusta Public Transit GA Avila Trolley CA Baker City Community Connection OR Banning Transit CA Barstow Area Transit CA Bart Bus WI Basin Transit Service OR Battle Creek Transit MI Bay Area Rapid Transit CA Bay Area Transportation Authority MI Bay Metro MI Bay State Cruise Company MA Bay Town Trolley FL Baylink CA BCTA (Beaver County Transit Authority) PA BE Line CA Beach Cities Transit - City of Redondo Beach (BCT) -

Transit Grant Summary

Revised 2/4/2020 NHDOT FTA SFY 17 Grant Applications: Projects Awarded - All Subrecipients service minority groups and low-income individuals within their service area. SFY 2017 PURCHASE OF SERVICE Regional Allocation Approved FTA $ 5310 POS Program: Seniors & Individuals with Disabilities Program Two Year Contract Region 1 - Grafton-Coos North Country Council $97,744 $97,744 Region 2 - Carroll County MWVEC $50,897 $50,897 Region 3 - Mid-State Central NH RPC $138,184 $138,184 Region 4 - Sullivan County UVLSRPC $50,126 $50,126 Region 5/6 - Monadnock Region County of Cheshire $96,291 $96,291 Region 7 - Nashua Region Nashua RPC $119,676 $119,676 Region 8 - Southern NH Southern NH Planning Commission $120,260 $120,260 Region 9 - Salem-Derry CART $81,376 $81,376 Region 10 - Southeast NH (ACT) Rockingham PC ACT (Seacoast) Region $162,728 $162,728 SUB TOTAL $917,282 $917,282 SFY 2016-2017 5310 FORMULA for Mobility Management Regional Allocation Approved FTA $ 5310 RCC Formula Distributed funds: Seniors & Individuals with Disabilities Program Two Year Contract Region 1 - Grafton-Coos North Country Council $72,382 $72,382 Region 2 - Carroll County North Country Council $28,739 $28,739 Region 3 - Mid-State Community Action Program Belknap-Merrimack Counties $163,788 $56,400 Region 4 - Sullivan County Community Alliance $28,072 $28,072 Region 5/6 - Monadnock Region Community Volunteer Transportation Company $52,395 $52,395 Region 7 - Nashua Region Nashua Regional Planning Commission $15,443 $15,443 Region 8 - Southern New Hampshire Southern New