The University of Chicago Playing an Epic Game: Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Select Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley

ENGLISH CLÀSSICS The vignette, representing Shelleÿs house at Great Mar lou) before the late alterations, is /ro m a water- colour drawing by Dina Williams, daughter of Shelleÿs friend Edward Williams, given to the E ditor by / . Bertrand Payne, Esq., and probably made about 1840. SELECT LETTERS OF PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY EDITED WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY RICHARD GARNETT NEW YORK D.APPLETON AND COMPANY X, 3, AND 5 BOND STREET MDCCCLXXXIII INTRODUCTION T he publication of a book in the series of which this little volume forms part, implies a claim on its behalf to a perfe&ion of form, as well as an attradiveness of subjeâ:, entitling it to the rank of a recognised English classic. This pretensión can rarely be advanced in favour of familiar letters, written in haste for the information or entertain ment of private friends. Such letters are frequently among the most delightful of literary compositions, but the stamp of absolute literary perfe&ion is rarely impressed upon them. The exceptions to this rule, in English literature at least, occur principally in the epistolary litera ture of the eighteenth century. Pope and Gray, artificial in their poetry, were not less artificial in genius to Cowper and Gray ; but would their un- their correspondence ; but while in the former premeditated utterances, from a literary point of department of composition they strove to display view, compare with the artifice of their prede their art, in the latter their no less successful cessors? The answer is not doubtful. Byron, endeavour was to conceal it. Together with Scott, and Kcats are excellent letter-writers, but Cowper and Walpole, they achieved the feat of their letters are far from possessing the classical imparting a literary value to ordinary topics by impress which they communicated to their poetry. -

Abstract Why We Turn the Page: a Literary Theory Of

ABSTRACT WHY WE TURN THE PAGE: A LITERARY THEORY OF DYNAMIC STRUCTURALISM Justin J. J. Ness, Ph.D. Department of English Northern Illinois University, 2019 David J. Gorman, Director This study claims that every narrative text intrinsically possesses a structure of fixed relationships among its interest components. The progress of literary structuralism gave more attention to the static nature of what a narrative is than it did to the dynamic nature of how it operates. This study seeks to build on the work of those few theorists who have addressed this general oversight and to contribute a more comprehensive framework through which literary critics may better chart the distinct tensions that a narrative text cultivates as it proactively produces interest to motivate a reader’s continued investment therein. This study asserts that the interest in narrative is premised on three affects— avidity, anxiety, and curiosity—and that tensions within the text are developed through five components of discourse: event, description, dialog, sequence, and presentation. NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DEKALB, ILLINOIS MAY 2019 WHY WE TURN THE PAGE: A LITERARY THEORY OF DYNAMIC STRUCTURALISM BY JUSTIN J. J. NESS ©2019 Justin J. J. Ness A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Dissertation Director: David J. Gorman ACKNOWLEDGMENTS David Gorman, the director of my project, introduced me to literary structuralism six years ago and has ever since challenged me to ask the simple questions that most people take for granted, to “dare to be stupid.” This honesty about my own ignorance was—in one sense, perhaps the most important sense—the beginning of my life as a scholar. -

CALIFORNIA's NORTH COAST: a Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors

CALIFORNIA'S NORTH COAST: A Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors. A Geographically Arranged Bibliography focused on the Regional Small Presses and Local Authors of the North Coast of California. First Edition, 2010. John Sherlock Rare Books and Special Collections Librarian University of California, Davis. 1 Table of Contents I. NORTH COAST PRESSES. pp. 3 - 90 DEL NORTE COUNTY. CITIES: Crescent City. HUMBOLDT COUNTY. CITIES: Arcata, Bayside, Blue Lake, Carlotta, Cutten, Eureka, Fortuna, Garberville Hoopa, Hydesville, Korbel, McKinleyville, Miranda, Myers Flat., Orick, Petrolia, Redway, Trinidad, Whitethorn. TRINITY COUNTY CITIES: Junction City, Weaverville LAKE COUNTY CITIES: Clearlake, Clearlake Park, Cobb, Kelseyville, Lakeport, Lower Lake, Middleton, Upper Lake, Wilbur Springs MENDOCINO COUNTY CITIES: Albion, Boonville, Calpella, Caspar, Comptche, Covelo, Elk, Fort Bragg, Gualala, Little River, Mendocino, Navarro, Philo, Point Arena, Talmage, Ukiah, Westport, Willits SONOMA COUNTY. CITIES: Bodega Bay, Boyes Hot Springs, Cazadero, Cloverdale, Cotati, Forestville Geyserville, Glen Ellen, Graton, Guerneville, Healdsburg, Kenwood, Korbel, Monte Rio, Penngrove, Petaluma, Rohnert Part, Santa Rosa, Sebastopol, Sonoma Vineburg NAPA COUNTY CITIES: Angwin, Calistoga, Deer Park, Rutherford, St. Helena, Yountville MARIN COUNTY. CITIES: Belvedere, Bolinas, Corte Madera, Fairfax, Greenbrae, Inverness, Kentfield, Larkspur, Marin City, Mill Valley, Novato, Point Reyes, Point Reyes Station, Ross, San Anselmo, San Geronimo, San Quentin, San Rafael, Sausalito, Stinson Beach, Tiburon, Tomales, Woodacre II. NORTH COAST AUTHORS. pp. 91 - 120 -- Alphabetically Arranged 2 I. NORTH COAST PRESSES DEL NORTE COUNTY. CRESCENT CITY. ARTS-IN-CORRECTIONS PROGRAM (Crescent City). The Brief Pelican: Anthology of Prison Writing, 1993. 1992 Pelikanesis: Creative Writing Anthology, 1994. 1994 Virtual Pelican: anthology of writing by inmates from Pelican Bay State Prison. -

HNA April 11 Cover-Final.Indd

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 28, No. 1 April 2011 Jacob Cats (1741-1799), Summer Landscape, pen and brown ink and wash, 270-359 mm. Hamburger Kunsthalle. Photo: Christoph Irrgang Exhibited in “Bruegel, Rembrandt & Co. Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850”, June 17 – September 11, 2011, on the occasion of the publication of Annemarie Stefes, Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850, Kupferstichkabinett der Hamburger Kunsthalle (see under New Titles) HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone/Fax: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President - Stephanie Dickey (2009–2013) Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Vice-President - Amy Golahny (2009–2013) Lycoming College Williamsport, PA 17701 Treasurer - Rebecca Brienen University of Miami Art & Art History Department PO Box 248106 Coral Gables FL 33124-2618 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Board Members Contents Dagmar Eichberger (2008–2012) HNA News ............................................................................1 Wayne Franits (2009–2013) Matt Kavaler (2008–2012) Personalia ............................................................................... 2 Henry Luttikhuizen (2009 and 2010–2014) Exhibitions -

University of Cincinnati

! "# $ % & % ' % !" #$ !% !' &$ &""! '() ' #$ *+ ' "# ' '% $$(' ,) * !$- .*./- 0 #!1- 2 *,*- Atomic Apocalypse – ‘Nuclear Fiction’ in German Literature and Culture A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the Department of German Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences 2010 by Wolfgang Lueckel B.A. (equivalent) in German Literature, Universität Mainz, 2003 M.A. in German Studies, University of Cincinnati, 2005 Committee Chair: Sara Friedrichsmeyer, Ph.D. Committee Members: Todd Herzog, Ph.D. (second reader) Katharina Gerstenberger, Ph.D. Richard E. Schade, Ph.D. ii Abstract In my dissertation “Atomic Apocalypse – ‘Nuclear Fiction’ in German Literature and Culture,” I investigate the portrayal of the nuclear age and its most dreaded fantasy, the nuclear apocalypse, in German fictionalizations and cultural writings. My selection contains texts of disparate natures and provenance: about fifty plays, novels, audio plays, treatises, narratives, films from 1946 to 2009. I regard these texts as a genre of their own and attempt a description of the various elements that tie them together. The fascination with the end of the world that high and popular culture have developed after 9/11 partially originated from the tradition of nuclear fiction since 1945. The Cold War has produced strong and lasting apocalyptic images in German culture that reject the traditional biblical apocalypse and that draw up a new worldview. In particular, German nuclear fiction sees the atomic apocalypse as another step towards the technical facilitation of genocide, preceded by the Jewish Holocaust with its gas chambers and ovens. -

“Life” — Sam Rein Solo Exhibition at Barrett Art Center by RAYMOND J

Inside: Raleigh on Film; Bethune on Theatre; Behrens on Music; Marvel’s ‘Art Byte’; th Critique: Sam Rein at Barrett Art Center; Year! Seckel on the Cultural Scene; Jeanne Heiberg & John Coyne ‘Speak Out’; Our 25 New Art Books; Short Fiction & Poetry; Extensive Calendar of Events…and more! ART TIMES Vol. 25 No. 6 Jan/Feb 2009 “Life” — Sam Rein Solo Exhibition at Barrett Art Center By RAYMOND J. STEINER IT’S ALWAYS A distinct pleasure sional surface alive not only to the for this viewer to come across a eye, but also to the spirit and soul. working artist from the “old school” A humanist with wit, perception, — you know, someone who can draw, and sensitivity, Sam Rein could not manipulate a paint-laden brush, have chosen a more fitting title for compose a motif, vary a ‘signature’, this solo exhibition* since “Life” so avoid a hackneyed formula that aptly reveals his long love affair with “sells”…in brief, bring a two-dimen- the pathos and bathos of the human River View Watercolor condition. This is an artist who not imagery (“Track Three”; “Table Talk only loves his craft, but who also is Al Fresco” — a charming genre piece in sympathy with the nature of be- of three oldsters conversing around ing — whether it be person, object, an outdoor table) is compelling, in- or landscape. viting the viewer to enter, to partici- Some thirty-seven works — pate in whatever is unfolding before charcoals, pastels, watercolors, the eye. Especially “present” in their gouaches, acrylics and even a pencil “thereness” — what the early Ger- drawing (“Reclining Nude, Head on man aestheticians referred to as the Hand”) — make up this show, more ding an sich (the thing in itself) — than enough to showcase Rein’s ver- are his studies of the female figure, satility in motif, genre, and in style. -

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis Romanische Literaturen der Welt Herausgegeben von Ottmar Ette Band 61 Petrarch and Boccaccio The Unity of Knowledge in the Pre-modern World Edited by Igor Candido An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. The Open Access book is available at www.degruyter.com. ISBN 978-3-11-042514-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041930-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041958-0 ISSN 0178-7489 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 license. For more information, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Igor Candido, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Konvertus, Haarlem Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Dedicated to Ronald Witt (1932–2017) Contents Acknowledgments IX Igor Candido Introduction 1 H. Wayne Storey The -

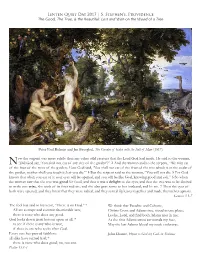

Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel, the Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man (1617)

Lenten Quiet Day 2017 | S. Stephen’s, Providence The Good, The True, & the Beautiful: Lost and Won on the Wood of a Tree Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel, The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man (1617) ow the serpent was more subtle than any other wild creature that the Lord God had made. He said to the woman, N“Did God say, ‘You shall not eat of any tree of the garden’?” 2 And the woman said to the serpent, “We may eat of the fruit of the trees of the garden; 3 but God said, ‘You shall not eat of the fruit of the tree which is in the midst of the garden, neither shall you touch it, lest you die.’” 4 But the serpent said to the woman, “You will not die. 5 For God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.” 6 So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate; and she also gave some to her husband, and he ate. 7 Then the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together and made themselves aprons. Genesis 3.1-7 The fool has said in his heart, “There is no God.” * We think that Paradise and Calvarie, All are corrupt and commit abominable acts; Christs Cross and Adams tree, stood in one place; there is none who does any good. -

Ribera's Drunken Silenusand Saint Jerome

99 NAPLES IN FLESH AND BONES: RIBERA’S DRUNKEN SILENUS AND SAINT JEROME Edward Payne Abstract Jusepe de Ribera did not begin to sign his paintings consistently until 1626, the year in which he executed two monumental works: the Drunken Silenus and Saint Jerome and the Angel of Judgement (Museo di Capodimonte, Naples). Both paintings include elaborate Latin inscriptions stating that they were executed in Naples, the city in which the artist had resided for the past decade and where he ultimately remained for the rest of his life. Taking each in turn, this essay explores the nature and implications of these inscriptions, and offers new interpretations of the paintings. I argue that these complex representations of mythological and religious subjects – that were destined, respectively, for a private collection and a Neapolitan church – may be read as incarnations of the city of Naples. Naming the paintings’ place of production and the artist’s city of residence in the signature formulae was thus not coincidental or marginal, but rather indicative of Ribera inscribing himself textually, pictorially and corporeally in the fabric of the city. Keywords: allegory, inscription, Naples, realism, Jusepe de Ribera, Saint Jerome, satire, senses, Silenus Full text: http://openartsjournal.org/issue-6/article-5 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5456/issn.2050-3679/2018w05 Biographical note Edward Payne is Head Curator of Spanish Art at The Auckland Project and an Honorary Fellow at Durham University. He previously served as the inaugural Meadows/Mellon/Prado Curatorial Fellow at the Meadows Museum (2014–16) and as the Moore Curatorial Fellow in Drawings and Prints at the Morgan Library & Museum (2012–14). -

Boccaccio on Readers and Reading

Heliotropia 1.1 (2003) http://www.heliotropia.org Boccaccio on Readers and Reading occaccio’s role as a serious theorist of reading has not been a partic- ularly central concern of critics. This is surprising, given the highly B sophisticated commentary on reception provided by the two autho- rial self-defenses in the Decameron along with the evidence furnished by the monumental if unfinished project of his Dante commentary, the Espo- sizioni. And yet there are some very interesting statements tucked into his work, from his earliest days as a writer right to his final output, about how to read, how not to read, and what can be done to help readers. That Boccaccio was aware of the way genre affected the way people read texts is evident from an apparently casual remark in the Decameron. Having declared that his audience is to be women in love, he then announ- ces the contents of his book: intendo di raccontare cento novelle, o favole o parabole o istorie che dire le vogliamo. (Decameron, Proemio 13) The inference is that these are precisely the kinds of discourse appropriate for Boccaccio’s intended readership, lovelorn ladies. Attempts to interpret this coy list as a typology of the kinds of narration in the Decameron have been rather half-hearted, especially in commented editions. Luigi Russo (1938), for instance, makes no mention of the issue at all, and the same goes for Bruno Maier (1967) and Attilio Momigliano (1968). Maria Segre Consigli (1966), on the other hand, limits herself to suggesting that the three last terms are merely synonyms used by the author to provide a working definition of the then-unfamiliar term ‘novella’. -

Locating Boccaccio in 2013

Locating Boccaccio in 2013 Locating Boccaccio in 2013 11 July to 20 December 2013 Mon 12.00 – 5.00 Tue – Sat 10.00 – 5.00 Sun 12.00 – 5.00 The John Rylands Library The University of Manchester 150 Deansgate, Manchester, M3 3EH Designed by Epigram 0161 237 9660 1 2 Contents Locating Boccaccio in 2013 2 The Life of Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375) 3 Tales through Time 4 Boccaccio and Women 6 Boccaccio as Mediator 8 Transmissions and Transformations 10 Innovations in Print 12 Censorship and Erotica 14 Aesthetics of the Historic Book 16 Boccaccio in Manchester 18 Boccaccio and the Artists’ Book 20 Further Reading and Resources 28 Acknowledgements 29 1 Locating Boccaccio Te Life of Giovanni in 2013 Boccaccio (1313-1375) 2013 is the 700th anniversary of Boccaccio’s twenty-first century? His status as one of the Giovanni Boccaccio was born in 1313, either Author portrait, birth, and this occasion offers us the tre corone (three crowns) of Italian medieval in Florence or nearby Certaldo, the son of Decameron (Venice: 1546), opportunity not only to commemorate this literature, alongside Dante and Petrarch is a merchant who worked for the famous fol. *3v great author and his works, but also to reflect unchallenged, yet he is often perceived as Bardi company. In 1327 the young Boccaccio upon his legacy and meanings today. The the lesser figure of the three. Rather than moved to Naples to join his father who exhibition forms part of a series of events simply defining Boccaccio in automatic was posted there. As a trainee merchant around the world celebrating Boccaccio in relation to the other great men in his life, Boccaccio learnt the basic skills of arithmetic 2013 and is accompanied by an international then, we seek to re-present him as a central and accounting before commencing training conference held at the historic Manchester figure in the classical revival, and innovator as a canon lawyer. -

Filostrato: an Unintentional Comedy?

Heliotropia 15 (2018) http://www.heliotropia.org Filostrato: an Unintentional Comedy? he storyline of Filostrato is easy to sum up: Troiolo, who is initially presented as a Hippolytus-type character, falls in love with Criseida. T Thanks to the mediation of Pandaro, mezzano d’amore, Troiolo and Criseida can very soon meet and enjoy each other’s love. Criseida is then unfortunately sent to the Greek camp, following an exchange of prisoners between the fighting opponents. Here she once again very quickly falls in love, this time with the Achaean warrior Diomedes. After days of emotional turmoil, Troiolo accidentally finds out about the affair: Diomedes is wearing a piece of jewellery that he had previously given to his lover as a gift.1 The young man finally dies on the battlefield in a rather abrupt fashion: “avendone già morti più di mille / miseramente un dì l’uccise Achille” [And one day, after a long stalemate, when he already killed more than a thou- sand, Achilles slew him miserably] (8.27.7–8). This very minimal plot is told in about 700 ottave (roughly the equivalent of a cantica in Dante’s Comme- dia), in which dialogues, monologues, and laments play a major role. In fact, they tend to comment on the plot, rather than feed it. I would insert the use of love letters within Filostrato under this pragmatic rationale: the necessity to diversify and liven up a plot which we can safely call flimsy. We could read the insertion of Cino da Pistoia’s “La dolce vista e ’l bel sguardo soave” (5.62–66) under the same lens: a sort of diegetic sublet that incorporates the words of someone else, in this case in the form of a poetic homage.2 Italian critics have insisted on the elegiac nature of Filostrato, while at the same time hinting at its ambiguous character, mainly in terms of not 1 “Un fermaglio / d’oro, lì posto per fibbiaglio” [a brooch of gold, set there perchance as clasp] (8.9).