What If the Grand Canyon Had Become the Second National Park?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIBLIOGRAPHY for VERDE RIVER WATERSHED PROJECT. Originally Compiled by Jim Byrkit, Assisted by Bruce Hooper, Both of Northern Arizona University

BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR VERDE RIVER WATERSHED PROJECT. Originally compiled by Jim Byrkit, assisted by Bruce Hooper, both of Northern Arizona University. Abbey, Edward.(1) 1968. Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness. New York, NY: Ballantine; McGraw- Hill. NAU PS3551.B225. Also in SC. Abbey, Edward.(1) 1986. "Even the Bad Guys Wear White Hats: Cowboys, Ranchers, and Ruin of the West." Harper's, Vol. 272, No. 1628 (January), pp. 51-55. NAU AP2.H3.V272. Abeytia, Lt. Antonio.(1) 1865. "Letter to the Assistant Adjutant General of the District of Arizona for transmission to Brigadier General John S. Mason from Rio Verde, Arizona." Published in the 17th Annual Fort Verde Day Brochure, October 13, 1973, p. 62. (August 29) (Files of the Camp Verde Historical Society) NAU SC F819.C3C3 1973. ("1st Lt. A. Abeytia's Letter.") Adamus, Paul R.(1) 1986. Final Work Plan, Mendenhall Valley Wetland Assessment Project Calibration Studies. Adamus Resource Assessment, Inc. (NAU no) Adamus, Paul R., and L. T. Stockwell.(1) 1983. A Method for Wetland Functional Assessment, Vol. 1. Report No. FHWA-IP-82 23. U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Offices of Research and Development. 2 Vols. NAU Gov. Docs. TD 2.36:82-24. Adamus, Paul R., et al. (Daniel R. Smith?)(1) 1987. Wetland Evaluation Technique (WET); Volume II: Methodology. Operational Draft Technical Report Y-87- (?). Vicksburg, MS: U.S. Army Engineer Waterways Experiment Station. (NAU no) Ahmed, Muddathir Ali.(2) 1965. "Description of the Salt River Project and Impact of Water Rights on Optimum Farm Organization and Values." MA Thesis, University of Arizona. -

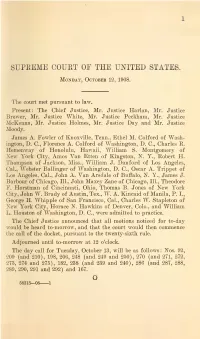

1908 Journal

1 SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES. Monday, October 12, 1908. The court met pursuant to law. Present: The Chief Justice, Mr. Justice Harlan, Mr. Justice Brewer, Mr. Justice White, Mr. Justice Peckham, Mr. Justice McKenna, Mr. Justice Holmes, Mr. Justice Day and Mr. Justice Moody. James A. Fowler of Knoxville, Tenn., Ethel M. Colford of Wash- ington, D. C., Florence A. Colford of Washington, D. C, Charles R. Hemenway of Honolulu, Hawaii, William S. Montgomery of Xew York City, Amos Van Etten of Kingston, N. Y., Robert H. Thompson of Jackson, Miss., William J. Danford of Los Angeles, Cal., Webster Ballinger of Washington, D. C., Oscar A. Trippet of Los Angeles, Cal., John A. Van Arsdale of Buffalo, N. Y., James J. Barbour of Chicago, 111., John Maxey Zane of Chicago, 111., Theodore F. Horstman of Cincinnati, Ohio, Thomas B. Jones of New York City, John W. Brady of Austin, Tex., W. A. Kincaid of Manila, P. I., George H. Whipple of San Francisco, Cal., Charles W. Stapleton of Mew York City, Horace N. Hawkins of Denver, Colo., and William L. Houston of Washington, D. C, were admitted to practice. The Chief Justice announced that all motions noticed for to-day would be heard to-morrow, and that the court would then commence the call of the docket, pursuant to the twenty-sixth rule. Adjourned until to-morrow at 12 o'clock. The day call for Tuesday, October 13, will be as follows: Nos. 92, 209 (and 210), 198, 206, 248 (and 249 and 250), 270 (and 271, 272, 273, 274 and 275), 182, 238 (and 239 and 240), 286 (and 287, 288, 289, 290, 291 and 292) and 167. -

Fine Americana Travel & Exploration with Ephemera & Manuscript Material

Sale 484 Thursday, July 19, 2012 11:00 AM Fine Americana Travel & Exploration With Ephemera & Manuscript Material Auction Preview Tuesday July 17, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wednesday, July 18, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Thursday, July 19, 9:00 am to 11:00 am Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www.pbagalleries. com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. CONSIGN TO PBA GALLERIES PBA is always happy to discuss consignments of books, maps, photographs, graphics, autographs and related material. -

Congressional Record-Senate

2432 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. FEBRUARY 21, bill to forbid the sale of intoxicating liquors in all Government am entirely in order in making the request I have made, and that buildings, etc.-to the Committee on Alcoholic Liquor Traffic. it is not a technicality. Also, petition of Wolverine Division, No. 182, Ordru: of Railway The PRESIDENT pro tempore. There is only an hour to be Conductors, Jackson, Mich., favoring the Foraker safety-appli given to legislative business. If there be no objection, the Chair ance bill-to the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. will receive morning b~siness. By Mr. REEDER: Petitions of the Western Retail Implement ROCK ISLAND ARSENAL, ILLINOIS. and Vehicle Dealers' Association, of Abilene Kans.; also of nu The PRESIDENT pro tempore laid before the Senate a com merous dtizens of the Sixth Congressional district of Kansas. in munication from the Secretary of the Treasury transmitting a opposition to the parcels-post law-to the Committee on the Post letter from the Assistant Secretary of War, submitting an esti Office and Post-Roads. mate of appropriation for Rock 4land Arsenal, R ock Island ill., Also, resolutions of Lincoln Post, No.1, Grand Army of the Re $185 000 to replace a storehouse destroyed by fire February 11, public, Department of Kansas against the erection of monuments 1903; which, with the accompanying papers, was refen·ed to the on United States grounds in honor of those who fought against the Union-to the Committee on the Library. Committee on Appropriations, and ordered to be printed. By Mr. -

An Adm I N I Strati Ve History of Grand Ca Nyon Nati Onal Pa R K Becomingchapter a Natio Onenal Park -

Figure 1.Map ofGrand Canyon National Monument/Grand Canyon Game Preserve, National Game Preserve (created by Roosevelt in 1906),and unassigned public domain. ca.1906-10. President Theodore Roosevelt liberally interpreted the 1906 Antiquities Act The U.S.Forest Service managed the monument from 1908 until it became a national when he established by proclamation the 1,279-square-milerand G Canyon National park in 1919, relying entirely on the Santa Fe Railroad to invest in roads,trails,and Monument in 1908.The monument was carved from Grand Canyon National Forest amenities to accommodate a budding tourism industry. (created by President Benjamin Harrison as a forest reserve in 1893), Grand Canyon an adm i n i strati ve history of grand ca nyon nati onal pa r k BecomingChapter a Natio Onenal Park - In the decades after the Mexican-American War, federal explorers and military in the Southwest located transportation routes, identified natural resources, and brushed aside resistant Indian peo p l e s . It was during this time that Europ ean America n s , fo ll o wing new east-west wagon roads, approached the rim of the Grand Canyon.1 The Atlantic & Pacific Railroad’s arrival in the Southwest accelerated this settlement, opening the region to entrepreneurs who initially invested in traditional economic ventures.Capitalists would have a difficult time figuring out how to profitably exploit the canyon,how- ever, biding their time until pioneers had pointed the way to a promising export economy: tourism. Beginning in the late 1890s, conflicts erupted between individualists who had launched this nascent industry and corporations who glimpsed its potential. -

Historical Development of Water Resources at the Grand Canyon

Guide Feb 7-8, 2015 Training Pioneer Trails Seminar “to” Grand Canyon by Dick Brown Grand Canyon Historical Society Pioneers of the Grand Canyon Seth B. Tanner* Niles J. Cameron* Louis D. Boucher* William F. Hull* Peter D. Berry* Babbitt Brothers John Hance* John A. Marshall Ellsworth Kolb William W. Bass* William O. O’Neill Emery Kolb William H. Ashurst Daniel L. Hogan* Charles J. Jones* Ralph H. Cameron* Sanford H. Rowe James T. Owens* * Canyon Guides By one means or another, and by a myriad of overland pathways, these pioneers eventually found their way to this magnificent canyon. Seth Benjamin Tanner Trailblazer & Prospector . Born in 1828, Bolton Landing, on Lake George in Adirondack Mountains, NY . Family joined Mormon westward migration . Kirtland, OH in 1834; Far West, MO in 1838; IL in 1839; IA in 1840 . Family settled in "the promised land" near Great Salt Lake in 1847 . Goldfields near Sacramento, CA in 1850 . Ranching in San Bernardino, CA (1851-1858) . Married Charlotte Levi, 1858, Pine Valley, UT, seven children, Charlotte died in 1872 . Led Mormon scouting party in 1875, Kanab to Little Colorado River . Married Anna Jensen, 1876, Salt Lake City, settled near today’s Cameron Trading Post . In 1880, organized Little Colorado Mining District and built Tanner Trail . Later years, Seth (then blind) & Annie lived in Taylor, 30 miles south of Holbrook, AZ Photo Courtesy of John Tanner Family Association . Seth died in 1918 William Francis Hull Sheep Rancher & Road Builder . Four brothers: William (born in 1865), Phillip, Joseph & Frank . Hull family came from CA & homesteaded Hull Cabin near Challender, southeast of Williams . -

New Hance Trail

National Park Service Grand Canyon U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Arizona New Hance Trail In 1883, "Captain" John Hance became the first European American to settle at the Grand Canyon. He originally built his trails for mining, but quickly determined the real money lay in work as a guide and hotel manager. From the very start of his tourism business, with his Tennessee drawl, spontaneous wit, uninhibited imagination, and ability to never repeat a tale in exactly the same way, he developed a reputation as an eccentric and highly entertaining storyteller. The scattered presence of abandoned asbestos and copper mines are a reminder of his original intentions for the area. Shortly after his arrival, John improved an old Havasupai trail at the head of today's Hance Creek drainage, the "Old Hance Trail," but it was subject to frequent washouts. When rockslides made it impassable he built the New Hance Trail down Red Canyon. Today's trail very closely follows the trail built in 1894. The New Hance Trail developed a reputation similar to that of the original trail, eliciting the following comment from travel writer Burton Homes in 1904 (he did not exaggerate by much): There may be men who can ride unconcernedly down Hance's Trail, but I confess I am not one of them. My object in descending made it essential that I should live to tell the tale, and therefore, I mustered up sufficient moral courage to dismount and scramble down the steepest and most awful sections of the path on foot …. -

Chapter Three

CIrhapteronic Golden T Yhreeears - The s at Grand Canyon National Park witnessed a seamless progression of building pro- grams begun in the mid-s.The two decades were linked as well by persistence with earlier efforts to enhance visitors’experiences and protect the landscape through educational programs,bound- ary extensions, and the elimination of private and state inholdings. The continuity seems odd at first glance, as it accompanied the deepest economic depression the nation has yet endured. This cyclical malady of world capitalism might have resulted in reduced federal spending, a return to traditional extraction of resources, or a nonstructural approach to park management. Instead, it triggered federal subsidies in the form of emergency building funds and a ready supply of desperate low-wage laborers.Under Miner Tillotson,one of the better park superintendents by NPS standards,a mature administration took full and efficient advantage of national economic woes to complete structural improvements that,given World War and subsequent financial scrimping, might never have been built. In contrast to the misery of national unemployment,homelessness,dust bowls,and bread lines,financial circumstances com- bined with a visitational respite to produce a few golden years at many of the West’s national parks,including Grand Canyon. From an administrative perspective, staffing and base fund- $, annually. Normal road and trail funds diminished, ing remained at late-s levels through , as if there causing several new projects to be delayed, but deficits were had been no stock market crash and deepening financial offset by modest emergency funds of the Hoover collapse. Permanent employees in consisted of the Administration that allowed those projects already in superintendent, an assistant superintendent, chief ranger, progress to continue unabated. -

Wes Hildreth

Transcription: Grand Canyon Historical Society Interviewee: Wes Hildreth (WH), Jack Fulton (JF), Nancy Brown (NB), Diane Fulton (DF), Judy Fierstein (JYF), Gail Mahood (GM), Roger Brown (NB), Unknown (U?) Interviewer: Tom Martin (TM) Subject: With Nancy providing logistical support, Wes and Jack recount their thru-hike from Supai to the Hopi Salt Trail in 1968. Date of Interview: July 30, 2016 Method of Interview: At the home of Nancy and Roger Brown Transcriber: Anonymous Date of Transcription: March 9, 2020 Transcription Reviewers: Sue Priest, Tom Martin Keys: Grand Canyon thru-hike, Park Service, Edward Abbey, Apache Point route, Colin Fletcher, Harvey Butchart, Royal Arch, Jim Bailey TM: Today is July 30th, 2016. We're at the home of Nancy and Roger Brown in Livermore, California. This is an oral history interview, part of the Grand Canyon Historical Society Oral History Program. My name is Tom Martin. In the living room here, in this wonderful house on a hill that Roger and Nancy have, are Wes Hildreth and Gail Mahood, Jack and Diane Fulton, Judy Fierstein. I think what we'll do is we'll start with Nancy, we'll go around the room. If you can state your name, spell it out for me, and we'll just run around the room. NB: I'm Nancy Brown. RB: Yeah. Roger Brown. JF: Jack Fulton. WH: Wes Hildreth. GM: Gail Mahood. DF: Diane Fulton. JYF: Judy Fierstein. TM: Thank you. This interview is fascinating for a couple different things for the people in this room in that Nancy assisted Wes and Jack on a hike in Grand Canyon in 1968 from Supai to the Little Colorado River. -

Congressional Record-Senate. August 21

4258 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. AUGUST 21, SENATE. .- .... ; veal sections 17, 18, and 19 of the act entitled ''An act to amend the national banking laws," approved May 13, 1908, the MONDAY, A ·ugust 21, 1911. repeal to take effect March 31, 1912 ; Prayer by the Chaplain, ·Rev. Ulysses G. B. Pierce, D. D. S. J. Res. 34. Joint resolution providing for additional lands The Jmunal of the proceedings of Saturday last was read and for Colorado under the provisions of the Carey Act; and approved. S. J. Res. 57. Joint resolution to admit the Territories of New Mexico and Arizona as States into the Union upon an equal ELECTIONS OF PRESIDENT PRO TEMl'ORE. footing with the original States. Mr. LODGE. Mr. President, at the beginning of the session, when the Senate was balloting for President pro tempore and PETITIONS AND MEMORIALS. I happened to be the occupant of the chair, I asked the Chief The VICE PRESIDENT presented the petition of Edmund J. Clerk, Henry H. Gilfry, if he would collect and prepare for the James, president of the University of Illinois, Urbana, Ill., pray use of the Senate the precedents in regard to previous elections ing that provision be made for continuing the work of the scien ot President pro tempore and all matters connected therewith. tific investigation by the National Monetary C0mmission, which An examination of the list re1'eals the fact that the subject ba<l was ordered to lie on the table. been many times under discussion in the Senate, involving the Mr. CULLOM presented a petition of sundry citizens of the 'powers of the Vice President to appoint. -

Boatman's Quarterly Review

boatman’s quarterly review Henry Falany the journal of the Grand Canyon River Guide’s, Inc. • voulme 29 number 2 summer 2016 the journal of Grand Canyon River Guide’s, Dear Eddy • Prez Blurb • Farewell • Ed Fund • To DC • Back of the Boat • Letter to a Young Swamper • Supt Retires • GTS 2016! • Lava Falls • Wait, is There More? Call Me No Name • GCRG Endowment • Youth • Cap’n Hance boatman’s quarterly review Dear Eddy …is published more or less quarterly by and for GRAND CANYON RIVER GUIDES. IN REFERENCE TO THE ARTICLE, Analysis of the Cooling GRAND CANYON RIVER GUIDES Rate of Fermented Beverages in the Grand Canyon BY is a nonprofit organization dedicated to REBECCA AND VIRGINIA ZAUNBRECHER, IN BQR VOLUME 29 NUMBER 1, SPRING 2016. Protecting Grand Canyon Setting the highest standards for the river profession HE DETAILED STUDY by the Zaunbrechers is a Celebrating the unique spirit of the river community welcome empirical demonstration of the Providing the best possible river experience TSeven-minute Immersion Conjecture, which the authors state, “asses [sic] the time period necessary General Meetings are held each Spring and Fall. Our to cool beer to river temperature” specifically, with Board of Directors Meetings are generally held the first respect to the cooling effect of “captive” hatch water Wednesday of each month. All innocent bystanders are versus “live” river water on zymurgic beverages. urged to attend. Call for details. The authors, however, have not fully addressed the STAFF peculiar observation that while the “Immersion -

Lockwood, Francis C Collection

MS 441 LOCKWOOD, FRANCIS C., 1864-1948 PAPERS, 1913-1946 DESCRIPTION This is a collection of 10 boxes of correspondence and manuscripts by Francis C. Lockwood who was a member of the University of Arizona faculty for 31 years. The collection consists of correspondence by and to Dr. Lockwood between 1913 and 1948. Of special note is correspondence to various Arizona residents and historical figures on information about Arizona history. In addition, correspondence also covers the work of Dr. Lockwood as chairman of the Kino Memorial Committee. Manuscript entail many of the lectures and programs present by Dr. Lockwood in Arizona and around the nation. 10 Boxes, 5 linear feet BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Francis C. Lockwood was born in Mount Erie, Illinois in 1864. He came to the University of Arizona as Professor of English in 1916. He served as Dean of College of Letters, Arts and Sciences from 1920 to 1930. Dr. Lockwood served as the acting president of the University of Arizona from 1922-1923. After 1930 he resigned as Dean and devoted his time to research, lecturing, and teaching. Dr. Lockwood remained with the University for 31 years with a brief departure in 1918 to serve overseas in the Army Educational Commission with the Y.M.C.A. As Dean for the College of Liberal Arts Dr. Lockwood was deeply interested in student welfare and education. In 1925 he co-authored with Dean Kate W. Jameson “The Freshmen Girl! A Campus Guide.” Dr. Lockwood was a well known lecturer with a strong interest in Arizona history and published numerous books and articles, including: If Kino Rode Today; Life In Old Tucson; The Old English Coffee House; Arizona Characters; Life of Edward E.