Chapter Three

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grand Canyon Getaway September 23-26, 2019 $1641.00

Golden Opportunity Grand Canyon Getaway September 23-26, 2019 $1641.00 (Double) $1985.00 (Single) Accepting Deposits (3-00.00) (Cash, credit card or check) $300.00 2nd Payment Due May 3, 2019 $300.00 3rd Payment Due June 7, 2019 $300.00 4th Payment Due July 5, 2 019 Balance due August 2, 2019 The Grand Canyon is 277 river miles long, up to 18 miles wide, and an average depth of one mile. Over 1,500 plant, 355 bird, 89 mammalian, 47 reptile, 9 amphibian, and 17 fish species. A part of the Colorado River basin that has taken over 40 million years to develop. Rock layers showcasing nearly two billion years of the Earth’s geological history. Truly, the Grand Canyon is one of the most spectacular and biggest sites on Earth. We will board our flight at New Orleans International Airport and fly into Flagstaff, AR., where we will take a shuttle to the Grand Canyon Railway Hotel in Williams, AR to spend our first night. The hotel, w hich is located adjacent to the historic Williams Depot, is walking distance to downtown Williams and its famed main street – Route 66. The hotel features rooms updated in 2015 and 2016 with an indoor swimming pool and a hot tub. Williams, AR. Is a classic mountain town located in the Ponderosa Pine forest at around 6,800 feet elevation. The town has a four-season climate and provides year-round activities, from rodeos to skiing. Dubbed the “Gateway to the Grand Canyon”, Williams Main Street is none other than the Mother Road herself – Route 66. -

Trip Planner

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon, Arizona Trip Planner Table of Contents WELCOME TO GRAND CANYON ................... 2 GENERAL INFORMATION ............................... 3 GETTING TO GRAND CANYON ...................... 4 WEATHER ........................................................ 5 SOUTH RIM ..................................................... 6 SOUTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 7 NORTH RIM ..................................................... 8 NORTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 9 TOURS AND TRIPS .......................................... 10 HIKING MAP ................................................... 12 DAY HIKING .................................................... 13 HIKING TIPS .................................................... 14 BACKPACKING ................................................ 15 GET INVOLVED ................................................ 17 OUTSIDE THE NATIONAL PARK ..................... 18 PARK PARTNERS ............................................. 19 Navigating Trip Planner This document uses links to ease navigation. A box around a word or website indicates a link. Welcome to Grand Canyon Welcome to Grand Canyon National Park! For many, a visit to Grand Canyon is a once in a lifetime opportunity and we hope you find the following pages useful for trip planning. Whether your first visit or your tenth, this planner can help you design the trip of your dreams. As we welcome over 6 million visitors a year to Grand Canyon, your -

Of North Rim Pocket

Grand Canyon National Park National Park Service Grand Canyon Arizona U.S. Department of the Interior Pocket Map North Rim Services Guide Services, Facilities, and Viewpoints Inside the Park North Rim Visitor Center / Grand Canyon Lodge Campground / Backcountry Information Center Services and Facilities Outside the Park Protect the Park, Protect Yourself Information, lodging, restaurants, services, and Grand Canyon views Camping, fuel, services, and hiking information Lodging, camping, food, and services located north of the park on AZ 67 Use sunblock, stay hydrated, take Keep wildlife wild. Approaching your time, and rest to reduce and feeding wildlife is dangerous North Rim Visitor Center North Rim Campground Kaibab Lodge the risk of sunburn, dehydration, and illegal. Bison and deer can Park in the designated parking area and walk to the south end of the parking Operated by the National Park Service; $18–25 per night; no hookups; dump Located 18 miles (30 km) north of North Rim Visitor Center; open May 15 to nausea, shortness of breath, and become aggressive and will defend lot. Bring this Pocket Map and your questions. Features new interpretive station. Reservation only May 15 to October 15: 877-444-6777 or recreation. October 20; lodging and restaurant. 928-638-2389 or kaibablodge.com exhaustion. The North Rim's high their space. Keep a safe distance exhibits, park ranger programs, restroom, drinking water, self-pay fee station, gov. Reservation or first-come, first-served October 16–31 with limited elevation (8,000 ft / 2,438 m) and of at least 75 feet (23 m) from all nearby canyon views, and access to Bright Angel Point Trail. -

Grand Canyon National Park

GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK • A R I Z 0 N A • UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Grand Canyon [ARIZONA] National Park United States Department of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Arno B. Cammerer, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1936 Rules and Regulations A HE following summary of rules is intended as a guide for all park visitors. You are respectfully requested to facilitate the best in park administration by carefully observing the regulations. Complete regu lations may be seen at the office of the Superintendent. Preservation of 7\[atural Features The first law of a national park is preservation. Disturbance, injury, or destruction in any way of natural features, including trees, flowers, and other vegetation, rocks, and all wildlife, is strictly prohibited. Penalties are imposed for removing fossils and Indian remains, such as arrowheads, etc. Camps Camp or lunch only in designated areas. All rubbish that will burn should be disposed of in camp fires. Garbage cans are provided for noninflammable refuse. Wood and water are provided in all designated camp grounds. Fires Fires are absolutely prohibited except in designated spots. Do not go out of sight of your camp, even for a few moments, without making sure that your fire is either out entirely or being watched. Dogs, Cats, or other Domestic Animals Such animals are prohibited on Government lands within the park except as allowed through permission of the Superintendent, secured from park rangers at entrances. Automobiles The speed limit of 35 miles an hour is rigidly enforced. -

BIBLIOGRAPHY for VERDE RIVER WATERSHED PROJECT. Originally Compiled by Jim Byrkit, Assisted by Bruce Hooper, Both of Northern Arizona University

BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR VERDE RIVER WATERSHED PROJECT. Originally compiled by Jim Byrkit, assisted by Bruce Hooper, both of Northern Arizona University. Abbey, Edward.(1) 1968. Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness. New York, NY: Ballantine; McGraw- Hill. NAU PS3551.B225. Also in SC. Abbey, Edward.(1) 1986. "Even the Bad Guys Wear White Hats: Cowboys, Ranchers, and Ruin of the West." Harper's, Vol. 272, No. 1628 (January), pp. 51-55. NAU AP2.H3.V272. Abeytia, Lt. Antonio.(1) 1865. "Letter to the Assistant Adjutant General of the District of Arizona for transmission to Brigadier General John S. Mason from Rio Verde, Arizona." Published in the 17th Annual Fort Verde Day Brochure, October 13, 1973, p. 62. (August 29) (Files of the Camp Verde Historical Society) NAU SC F819.C3C3 1973. ("1st Lt. A. Abeytia's Letter.") Adamus, Paul R.(1) 1986. Final Work Plan, Mendenhall Valley Wetland Assessment Project Calibration Studies. Adamus Resource Assessment, Inc. (NAU no) Adamus, Paul R., and L. T. Stockwell.(1) 1983. A Method for Wetland Functional Assessment, Vol. 1. Report No. FHWA-IP-82 23. U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Offices of Research and Development. 2 Vols. NAU Gov. Docs. TD 2.36:82-24. Adamus, Paul R., et al. (Daniel R. Smith?)(1) 1987. Wetland Evaluation Technique (WET); Volume II: Methodology. Operational Draft Technical Report Y-87- (?). Vicksburg, MS: U.S. Army Engineer Waterways Experiment Station. (NAU no) Ahmed, Muddathir Ali.(2) 1965. "Description of the Salt River Project and Impact of Water Rights on Optimum Farm Organization and Values." MA Thesis, University of Arizona. -

Arizona Historic Bridge Inventory | Pages 164-191

NPS Form 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet section number G, H page 156 V E H I C U L A R B R I D G E S I N A R I Z O N A Geographic Data: State of Arizona Summary of Identification and Evaluation Methods The Arizona Historic Bridge Inventory, which forms the basis for this Multiple Property Documentation Form [MPDF], is a sequel to an earlier study completed in 1987. The original study employed 1945 as a cut-off date. This study inventories and evaluates all of the pre-1964 vehicular bridges and grade separations currently maintained in ADOT’s Structure Inventory and Appraisal [SI&A] listing. It includes all structures of all struc- tural types in current use on the state, county and city road systems. Additionally it includes bridges on selected federal lands (e.g., National Forests, Davis-Monthan Air Force Base) that have been included in the SI&A list. Generally not included are railroad bridges other than highway underpasses; structures maintained by federal agencies (e.g., National Park Service) other than those included in the SI&A; structures in private ownership; and structures that have been dismantled or permanently closed to vehicular traffic. There are exceptions to this, however, and several abandoned and/or privately owned structures of particular impor- tance have been included at the discretion of the consultant. The bridges included in this Inventory have not been evaluated as parts of larger road structures or historic highway districts, although they are clearly integral parts of larger highway resources. -

Linen, Section 2, G to Indians

Arizona, Linen Radio Cards Post Card Collection Section 2—G to Indians-Apache By Al Ring LINEN ERA (1930-1945 (1960?) New American printing processes allowed printing on postcards with a high rag content. This was a marked improvement over the “White Border” postcard. The rag content also gave these postcards a textured “feel”. They were also cheaper to produce and allowed the use of bright dyes for image coloring. They proved to be extremely popular with roadside establishments seeking cheap advertising. Linen postcards document every step along the way of the building of America’s highway infra-structure. Most notable among the early linen publishers was the firm of Curt Teich. The majority of linen postcard production ended around 1939 with the advent of the color “chrome” postcard. However, a few linen firms (mainly southern) published until well into the late 50s. Real photo publishers of black & white images continued to have success. Faster reproducing equipment and lowering costs led to an explosion of real photo mass produced postcards. Once again a war interfered with the postcard industry (WWII). During the war, shortages and a need for military personnel forced many postcard companies to reprint older views WHEN printing material was available. Photos at 43%. Arizona, Linen Index Section 1: A to Z Agua Caliente Roosevelt/Dam/Lake Ajo Route 66 Animals Sabino Canyon Apache Trail Safford Arizona Salt River Ash Fork San Francisco Benson San Xavier Bisbee Scottsdale Canyon De Chelly Sedona/Oak Creek Canyon Canyon Diablo Seligman -

237 265 273 15 Staat Und Verwaltung Las Vegas Bis

STAAT UND VERWALTUNG 15 HIGHLIGHTS 21 ROUTENÜBERSICHT 29 LAS VEGAS BIS ZION NATIONAL PARK 33 A ZION NATIONAL PARK BIS BRYCE CANYON NATIONAL PARK 57 B ÜBER DEN SCENIC BYWAY 12 ZUM CAPITOL REEF NATIONAL PARK 75 C CAPITOL REEF NATIONAL PARK ZUM LAKE POWELL UND MESA VERDE NATIONAL PARK 99 D MESA VERDE NATIONAL PARK ÜBER MONUMENT VALLEY ZURÜCK ZUM LAKE POWELL 133 E LAKE POWELL ZUM GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK 163 F GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK ÜBER DIE ROUTE 66 ZUM LAKE MEAD UND LAS VEGAS 203 G WISSENSWERTES MIT SPRACHHILFE 237 STICHWORTVERZEICHNIS 265 KARTEN 273 AUSZUG AUS NatioNalparkroute uSa – SüdweSt 3. auflage ISBN 978-3-943176-23-0 © 2012 Conbook Medien GmbH. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. NP_USA_Suedwest_Innen_20120314.indd 1 15.03.2012 11:01:04 ɻ INHALTSVERZEICHNIS (,1/(,781* � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 9 67$$781'9(5:$/781*86$ � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � +,*+/,*+76 � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 5287(1h%(56,&+7 � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � Panaca 319 Uvada Springs . 56 Cedar Caliente P Beryl Jct. Newcastle City 143 318 93 M S Cedar A E B=,211$7,21$/3$5.%,6 Ash A 317 Enterprise Old Breaks NM Springs D Acoma Irontown Kanaraville O Ruins W Kolop Canyon %5<&(&$1<211$7,21$/3$5. � � 57 Alamo Elgin 15 V Veyo Zion A Pine L 18 Valley NP Cedar Breaks L Toquerville 9 E E Shivwits Spring- Y G dale R Carp N Hurricane National Monument . . A Santa Clara Rock- R Washington Desert St. George 59ville NWR N O Hildale Red Canyon . M Colorado City R Littlefield 399 Mormon O Mossy Cave . M Valley Wash Mesquite Pipe Spring 168 NM Bunkerville Moapa 15 Wolf Hole Bryce Canyon National Park . -

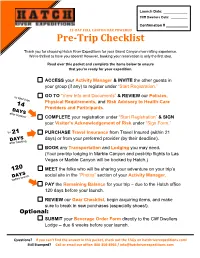

Pre-Trip Checklist

Launch Date: ____________ Cliff Dwellers Date: _________ Confirmation # ___________ 12-DAY FULL CANYON OAR POWERED Pre-Trip Checklist Thank you for choosing Hatch River Expeditions for your Grand Canyon river rafting experience. We’re thrilled to have you aboard! However, booking your reservation is only the first step. Read over this packet and complete the items below to ensure that you’re ready for your expedition. ACCESS your Activity Manager & INVITE the other guests in your group (if any) to register under “Start Registration.” GO TO “View Info and Documents” & REVIEW our Policies, Physical Requirements, and Risk Advisory to Health-Care Providers and Participants. COMPLETE your registration under “Start Registration” & SIGN your Visitor’s Acknowledgement of Risk under “Sign Form.” PURCHASE Travel Insurance from Travel Insured (within 21 days) or from your preferred provider (by their deadline). BOOK any Transportation and Lodging you may need. (Your pre-trip lodging in Marble Canyon and post-trip flights to Las Vegas or Marble Canyon will be booked by Hatch.) MEET the folks who will be sharing your adventure on your trip’s social site in the “Photos” section of your Activity Manager. PAY the Remaining Balance for your trip – due to the Hatch office 120 days before your launch. REVIEW our Gear Checklist, begin acquiring items, and make sure to break in new purchases (especially shoes!). Optional: SUBMIT your Beverage Order Form directly to the Cliff Dwellers Lodge – due 6 weeks before your launch. Questions? If you can’t find the answer in this packet, check out the FAQs on hatchriverexpeditions.com! Still Stumped? Call or email our office: 800-856-8966 / [email protected] 12 DAY FULL CANYON OAR POWERED Policies Registration Forms Cancellations You must complete a Registration Form for every guest If you must cancel your reservation more than 120 on your reservation within 14 days of making your days before your trip, you must notify us in writing. -

Scottsdale Grand Canyon Guide

SCOTTSDALE GRAND CANYON GUIDECLOSE BY – WORLDS AWAY THE GRAND CANYON is one of the trip. Looking for a quicker way to get there? Air tours most iconic locations in America. Every year, more depart from Scottsdale Airport and provide plenty of than 4 million visitors stand on her precipitous rim to time to explore the Canyon rim and still be back in marvel at nature’s artistry. You can do the same on Scottsdale in time for dinner. Scottsdale’s lush your next trip to Scottsdale! The Grand Canyon’s Sonoran Desert and the Grand Canyon’s water- and South Rim is a smooth 3 1/2-hour drive north of wind-carved geologic formations is a magical combi- Scottsdale, which makes it easy to go from city life to nation you won’t want to miss! remote relaxation on a full-day or leisurely overnight TWO GREAT DESTINATIONS, ONE GREAT EXPERIENCE SCOTTSDALE GRAND CANYON THE MAGICAL SONORAN DESERT AMERICA’S NATURAL WONDER Scottsdale’s sun-drenched Sonoran Desert setting provides a Considered by some to be one of the world’s Seven Natural Won- rugged and breathtaking backdrop for the city’s posh resorts and spas, ders, the Grand Canyon is an outdoor enthusiast’s paradise of stunning championship golf courses, and vibrant arts, dining and nightlife scenes. scenic views, miles of pristine trails and tour options by helicopter, river raft and shuttle bus. ROOM WITH A VIEW ROOM WITH A VIEW Accommodations in Scottsdale run the gamut from five-star luxury The historic El Tovar hotel, rustic lodges and cozy campgrounds are resorts in the scenic Sonoran Desert foothills to chic boutique hotels among your lodging options at the Grand Canyon’s popular South Rim. -

An Adm I N I Strati Ve History of Grand Ca Nyon Nati Onal Pa R K Becomingchapter a Natio Onenal Park -

Figure 1.Map ofGrand Canyon National Monument/Grand Canyon Game Preserve, National Game Preserve (created by Roosevelt in 1906),and unassigned public domain. ca.1906-10. President Theodore Roosevelt liberally interpreted the 1906 Antiquities Act The U.S.Forest Service managed the monument from 1908 until it became a national when he established by proclamation the 1,279-square-milerand G Canyon National park in 1919, relying entirely on the Santa Fe Railroad to invest in roads,trails,and Monument in 1908.The monument was carved from Grand Canyon National Forest amenities to accommodate a budding tourism industry. (created by President Benjamin Harrison as a forest reserve in 1893), Grand Canyon an adm i n i strati ve history of grand ca nyon nati onal pa r k BecomingChapter a Natio Onenal Park - In the decades after the Mexican-American War, federal explorers and military in the Southwest located transportation routes, identified natural resources, and brushed aside resistant Indian peo p l e s . It was during this time that Europ ean America n s , fo ll o wing new east-west wagon roads, approached the rim of the Grand Canyon.1 The Atlantic & Pacific Railroad’s arrival in the Southwest accelerated this settlement, opening the region to entrepreneurs who initially invested in traditional economic ventures.Capitalists would have a difficult time figuring out how to profitably exploit the canyon,how- ever, biding their time until pioneers had pointed the way to a promising export economy: tourism. Beginning in the late 1890s, conflicts erupted between individualists who had launched this nascent industry and corporations who glimpsed its potential. -

Grand Canyon Depot AND/OR COMMON

Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENTOF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___ TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Grand Canyon Depot AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER South Rim —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Grand Canyon National Park — VICINITY OF 3rd STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Arizona 04 Coconino 005 QCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT 3LPUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE ^.UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS ?_YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY X_OTHER:S tOrage (AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: inapplicable) National Park Service Western Regional Office STREET & NUMBER 450 Golden Gate Avenue, Box 36063______ ___ CITY, TOWN STATE San Francisco __ VICINITY OF California LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC Coconino County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER South San Francisco Street CITY. TOWN Flagstaff Atizona REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE National Register of Historic Places DATE 1974 X-FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS National Park Service CITY. TOWN STATE n f~ ni D. C DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE —GOOD —RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE______ X_FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE me brand Canyon Depot is a log and wood-frame structure with a central section two-and-a-half stories in height and wings to the east and west each one-and-a-half stories.