Gettysburg Historical Journal 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aaron David Stato Scarlatto Euroclub Abate Carmine La Collina Del Vento

aaron david stato scarlatto euroclub abate carmine la collina del vento mondadori abate carmine la festa del ritorno e altri viaggi mondolibri abbagnano nicola storia della filosofia,il pensiero greco e cri... gruppo editoriale l'espresso abécassis eliette il tesoro del tempio hachette abetti g. esplorazione dell'universo laterza abrami giovanni progettazione ambientale clup accoce pierre / quet pierre la guerra fu vinta in svizzera orpheus libri achard paul mes bonnes les editions de france ackermann walter en plein ciel librairie payot acton harold gli ultimi borboni di napoli martello adams douglas guida galattica per gli autostoppisti mondadori adams h. tre ragazze a londra malipiero adams richard i cani della peste rizzoli adams richard la ragazza sull'altalena narrativa club adams richard la valle dell'orso rizzoli adams scott dilbert (tm) la repubblica adamson joy regina di shaba club del libro adelson alan il diario di david sierakowiat einaudi adler david a. il mistero della casa stregata piemme junior adler elizabeth desideri privati speling & kupfer adler warren bugie private sperling paperback adler warren cuori sbandati euroclub adler warren la guerra dei roses berlusconi silvio editore adriani maurilio le religioni del mondo giunti-nardini Agassi, Andre Open la mia storia Giulio Einaudi Editore agee philip agente della cia editori riuniti agnellet michel cento anni di miracoli a lourdes mondadori arnoldo agnelli susanna vestivamo alla marinara mondadori Agnello Hornby, Simonetta La mia Londra Giunti Editore agostini franco giochi logici e matematici mondadori arnoldo editore agostini m.valeria europa comunitaria e partiti europei le monnier agrati gabriella / magini m.l.fiabe e leggende scozzesi (II vol.) mondadori agrati gabrielle / magini m.l.fiabe e leggende scozzesi (1 vol.) mondadori aguiar joao la stella a dodici punte le onde ahlberg allan dieci in un letto tea scuola ahrens dieter f. -

History of Midwifery in the US Parkland Memorial Hospital

History of Midwifery in the US Parkland Memorial Hospital Parkland School of Nurse Midwifery History of Midwifery in the US [Download this file in Text Format] Midwifery in the United States Native Americans had midwives within their various tribes. Midwifery in Colonial America began as an extension of European practices. It was noted that Brigit Lee Fuller attended three births on the Mayflower. Midwives filled a clear, important role in the colonies, one that Laurel Thatcher Ulrich explored in her Pulitzer Prize winning book: A Midwife's Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard Based on Her Diary 1785-1812. (Published in 1990). Midwifery was seen as a respectable profession, even warranting priority on ferry boats to the Colony of Massachusetts. Well skilled practitioners were actively sought by women. However, the apprentice model of training still predominated. A few private tutoring courses such as those offered by Dr. William Shippman, Jr. of Philadelphia existed, but were rare. The Midwifery Controversy The scientific nature of the nineteenth century education enabled an expansive knowledge explosion to occur in medical schools. The formalized medical communities and universities not only facilitated scientific inquiry, but also communicated new information on a variety of subjects including Pasteur's theory of infectious diseases, Holmes' and Semmelweis' work on puerperal fever, and Lister's writings on antisepsis. Since midwifery practice generally remained on an informal level, knowledge of this sophistication was not disseminated within the midwifery profession. Indeed, medical advances in pharmacology, hygiene and other practices were implemented routinely in obstetrics, without integration into midwifery practices. The homeopathic remedies and traditions practiced by generations of midwives began to appear in stark contrast to more "modern" remedies suggested by physicians. -

In Historic Moment for Diocese of Fort Worth, Four Men Are Ordained As Priests by Kathy Cribari Hamer Correspondent News Reports Hailed It As “His- Toric,” and St

NorthBringing the Good News to the Diocese Texas of Fort Worth Catholic Vol. 23 No. 11 July 27, 2007 In historic moment for Diocese of Fort Worth, four men are ordained as priests By Kathy Cribari Hamer Correspondent News reports hailed it as “his- toric,” and St. Patrick Cathedral in downtown Fort Worth was overfl owing with the faithful who recognized the signifi cance of the grand event. But Bishop Kevin Vann elevated the ordina- tions of four priests by offering his refl ection on fi ve profoundly simple words: “I am a Catholic priest.” Thomas Kennedy, Raymond McDaniel, Isaac Orozco, and Jon- athan Wallis entered the Order of Presbyter July 7, and the Diocese of Fort Worth received its largest group of newly ordained priests since its founding in1969. Enthu- siasm for the event had reached all parts of the diocese, such that the viewing of the event had to be extended to an additional room in the Fort Worth Convention Center, where the liturgy was projected on a huge screen. Families and friends came to the ordination to experience the traditional liturgy concel- NEWLY ORDAINED — Bishop Kevin Vann is joined at the eucharistic table by the diocese’s four newly ordained priests, Father Jonathan Wallis (left), Father Isaac ebrated by clergy who came Orozco (left of bishop), Father Raymond McDaniel (right of bishop), and Father Thomas Kennedy (right). The men were ordained to the Order of the Presbyter July from throughout the extended 7 at St. Patrick Cathedral in downtown Fort Worth. It was the largest ordination class in the history of the Diocese of Fort Worth. -

Titolo Autore Editore 12 Anni Schiavo Northup Solomon Garzanti 2

Titolo Autore Editore 12 anni schiavo Northup Solomon Garzanti 2. Bambini e muri indiani Macchiavelli, Luca Milano Edizioni dell'arco ; Barzago : Marna, 2003 a caccia di belve hunter j.a. bompiani a che punto è la notte fruttero & lucentini club degli editori a ciascuno il suo sciascia leonardo la biblioteca di repubblica a ciascuno il suo corpo rodgers mary mondadori a colloquio con lech walesa gatter-klenk jule rusconi a dio piacendo ormesson jean rizzoli a est di bisanzio dunnett dorothy corbaccio a immagine di cristo,la vita secondo locorti spirito renato tip.san gaudenzio no a milano non fa freddo marotta giuseppe bompiani a occidente del pecos grey zane sonzogno a ogni morte di papa andreotti giulio rizzoli a ogni uomo un soldo marshall bruce longanesi & c. a piedi nudi bianco damiano ep publiep a prova di killer child lee superpocket a rischio cornwewll patricia mondadori a room of one's own woolf virginia gordon a sangue freddo capote t. garzanti a short history of nearly everything bryson bill doubleday a solo higgins jack club italiano dei lettori mila a tavola con il diabete tomasi franco a tavola nell'ossola di corato riccardo comunitàmontana valle ossola a un cerbiatto somiglia il mio amore grossman david mondolibri spa a volte ritornano king stephen bompiani a.belcastro 1893-1961 gnemmi dario saccardo ornavasso aarn munro il gioviano john w.campbell jr. editrice nord abbaiare stanca pennac daniel salani abbasso le più carine benton jim piemme spa abbracciata dalla luce eadie betty j. euroclub abissi benchley peter club degli editori absolute friends le carré john coronet books accabadora murgia michela einaudi accadde tutto in una notte clark mary higgins mondadori accademia carrara della chiesa angela ottino ist.ital.d'arti graf.bergamo accidenti! perché non mi guarda? rayban chloe mondadori accidenti,perché non mi vuoi capire...hopkins cathy mondadori accroche-toi à ton reve bradford barbara taylor pierre belfond acqua in bocca camilleri andrea minimum fax roma ad occhi chiusi carofiglio gianrico sellerio ed. -

San Diego Public Library New Additions June 2009

San Diego Public Library New Additions June 2009 Adult Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities California Room 100 - Philosophy & Psychology CD-ROMs 200 - Religion Compact Discs 300 - Social Sciences DVD Videos/Videocassettes 400 - Language eAudiobooks & eBooks 500 - Science Fiction 600 - Technology Foreign Languages 700 - Art Genealogy Room 800 - Literature Graphic Novels 900 - Geography & History Large Print Audiocassettes Newspaper Room Audiovisual Materials Biographies Fiction Call # Author Title FIC/ABRAMS Abrams, Douglas Carlton. The lost diary of Don Juan FIC/ADDIEGO Addiego, John. The islands of divine music FIC/ADLER Adler, H. G. The journey : a novel FIC/AGEE Agee, James, 1909-1955. A death in the family [MYST] FIC/ALBERT Albert, Susan Wittig. The tale of Briar Bank : the cottage tales of Beatrix Potter FIC/ALBOM Albom, Mitch, 1958- The five people you meet in heaven FIC/ALCOTT Alcott, Louisa May The inheritance FIC/ALLBEURY Allbeury, Ted. Deadly departures FIC/AMBLER Ambler, Eric, 1909-1998. A coffin for Dimitrios FIC/AMIS Amis, Kingsley. Lucky Jim FIC/ARCHER Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- A prisoner of birth [MYST] FIC/ARRUDA Arruda, Suzanne Middendorf The leopard's prey : a Jade del Cameron mystery [MYST] FIC/ASHFORD Ashford, Jeffrey, 1926- A dangerous friendship [MYST] FIC/ATHERTON Atherton, Nancy. Aunt Dimity slays the dragon FIC/ATKINS Atkins, Charles. Ashes, ashes [MYST] FIC/ATKINSON Atkinson, Kate. When will there be good news? : a novel FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane, 1775-1817. Emma FIC/BAGGOTT Baggott, Julianna. Girl talk [MYST] FIC/BAIN Bain, Donald, 1935- A slaying in Savannah : a Murder, she wrote mystery, a novel [MYST] FIC/BAIN Bain, Donald, 1935- A vote for murder : a Murder, she wrote mystery : a novel [MYST] FIC/BAIN Bain, Donald, 1935- Margaritas & murder : a Murder, she wrote mystery : a novel FIC/BAKER Baker, Kage. -

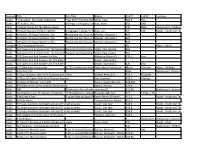

Elenco Libri in Ordine Alfabetico Per Titolo

ELENCO LIBRI IN ORDINE ALFABETICO PER TITOLO AGGIORNATO AL 21 GIUGNO 2013 Elenco libri in ordine alfabetico per titolo CODICE TITOLO AUTORE 8490 ... e la pioggia mia bevanda Suyin Han 3567 ... e la rosa - l'isola nel mondo Pini Adolfo 3318 ... e la vita continua Arlorio G. - Risi D. - Zapponi B. 5393 ... e poi non rimase nessuno Christie Agatha 9108 ... e venne chiamata due cuori Marlo Morgan 5832 ... e volen via! Brambilla Dugnani Paola 5771 ... e volen via! Dieci anni dopo Brambilla Dugnani Paola 5514 ... ricordiamo la pro magreglio … Romeo Maurizio 8003 007 licenza di avventura Fleming Jan 5360 007 licenza di uccidere Fleming Ian 3564 100 colpi di spazzola prima di andare a dormire Melissa P. 8821 101 modi per addormentare il tuo bambino rinaldi martina 8812 101 pezzi celebri classici e operistici rossi aldo 6734 101 storie zen Senzaki N - Reps P. 7671 150 anni andrea merzario Biagi E. - Folon J.M. - Roitier F. 7137 1882-1912: fare gli italiani Mola Aldo Alessandro 5733 1900-2000 - 100 anni di cronaca dal nostro territo autori vari 6570 1914 suicidio d'europa Romolotti Giuseppe 351 1915 obiettivo trento Pieropan Gianni 7124 1915-1917 guerra in ampezzo e cadore Berti Antonio 190 1917 lo sfondamento dell'isonzo Kraft Von Dellmensingen Konrad 1221 1919 la pace sbagliata Romolotti Giuseppe 7303 1943-1993 Biagi Enzo 7079 1983 anno santo della redenzione Carbone Mons.Carlo 7631 1990 il codice delle autonomie locali Sforza Fogliani C. - Maglia S. 1655 2 brave persone Cochi & Renato 5171 22 racconti d'amore da le mille e una notte Gabrielli Francesco 5478 25 anni di formula 1 Casucci P. -

Resource Typeitle Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Location Books

Resource TitleType Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Location Books "Impossible" Marriages Redeemed They Didn't End the StoryMiller, in the MiddleLeila 265.5 MIL Books "R" Father, The 14 Ways To Respond To TheHart, Lord's Mark Prayer 242 HAR DVDs 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family JUV Bible Audiovisual - Children's Books 10 Good Reasons To Be A Catholic A Teenager's Guide To TheAuer, Church Jim. Y/T 239 Books - Youth and Teen Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Compact Discs100 Inspirational Hymns CD Music - Adult Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 Books 101 Questions And Answers On Paul Witherup, Ronald D. 235.2 Paul Compact Discs101 Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. Books 101 Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. 220 BRO Compact Discs120 Bible Sing-Along songs & 120 Activities for Kids! Twin Sisters Productions Music Children Music - Children DVDs 13th Day, The DVD Audiovisual - Movies Books 15 days of prayer with Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton McNeil, Betty Ann 235.2 Elizabeth Books 15 Days Of Prayer With Saint Thomas Aquinas Vrai, Suzanne. -

Prek – 12 Religion Course of Study Diocese of Toledo 2018

PreK – 12 Religion Course of Study --- Diocese of Toledo --- 2018 PreK – 12 Religion Course of Study Diocese of Toledo 2018 Page 1 of 260 PreK – 12 Religion Course of Study --- Diocese of Toledo --- 2018 Page 2 of 260 PreK – 12 Religion Course of Study --- Diocese of Toledo --- 2018 TABLEU OF CONTENTS PreKU – 8 Course of Study U Introduction .......................................................................................................................7 PreK – 8 Content Structure: Scripture and Pillars of Catechism ..............................9 PreK – 8 Subjects by Grade Chart ...............................................................................11 Grade Pre-K ....................................................................................................................13 Grade K ............................................................................................................................20 Grade 1 ............................................................................................................................29 Grade 2 ............................................................................................................................43 Grade 3 ............................................................................................................................58 Grade 4 ............................................................................................................................72 Grade 5 ............................................................................................................................85 -

Submitted in Accordance with the Requirements for the Degree of In

AN INCARNATIONAL CHRISTOLOGY SET IN THE CONTEXT OF NARRATIVES OF SHONA WOMEN IN PRESENT DAY ZIMBABWE by FRANCISCA HILDEGARDIS CHIMHANDA Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY in the subject SYSTEMATIC THEOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: PROF EVAN NIEKERK JUNE2002 SUMMARY Implicit in the concepts Incarnation, narrative, Christology, Shona women of Zimbabwe today is the God who acts in human history and in the contemporaneity and particularity of our being. The Incarnation as the embodiment of God in the world entails seizing the kairos opportunity to expand the view and to bear the burdens ofresponsibility. A theanthropocosmic Christology that captures the Shona holistic world-view is explored. The acme for a relational Christology is the imago Dei!Christi and the baptismal indicative and imperative. God is revealed in various manifestations of creation. Human identity and dignity is the flipside of God's attributes. Theanthropocosmic Christology as pluralistic, differential and radical brings about a dialectic between the whole and its parts, the uniqueness of the individual, communal ontology and epistemology, the local and the universal, orthodoxy and orthopraxis, Christology and soteriology. God mediates in the contingency ofparticularity. Emphasis is on life-affirmation rather than sex determination of Jesus as indicated by theologies ofliberation and inculturation. At the interface gender, ethnicity, class and creed, God transcends human limitedness and artificial boundaries in creating catholic space and advocating all-embracing apostolic action. Difference is appreciated for the richness it brings both to the individual and the community. Hegemonic structures and borderless texts are view with suspicion as totalising grand-narratives and exclusivist by using generic language. -

1984 2,4 Miliardi Di Imprenditori 2010 Odissea Due 20

1935 E DINTORNI 1948, L'ANNO DELLO SCAMPATO PERICOLO 1953: FU VERA TRUFFA? 1984 2,4 MILIARDI DI IMPRENDITORI 2010 ODISSEA DUE 2012, LA FINE DEL MONDO? 2028 IL PERICOLO VIENE DAL CIELO 25 ANNI DI INFORMATICA ITALIANA 365 RICETTE RAPIDE 366 E PIU' STORIE DELLA NATURA 5 GIORNI A PARIGI 6 APRILE '96 6° RAPPORTO NEL PROCESSO DI LIBERALIZZAZIONE DELLA SOCIETA' ITALIANA 62 ESCURSIONI IN MONTAGNA 64 PC E C 64 A CARTE SCOPERTE A CERCAR LA BELLA MORTE A CHE PUNTO E' LA NEW ECONOMY IN ITALIA? A CHE PUNTO E' LA NOTTE A CIASCUNO IL SUO A CIASCUNO IL SUO MESTIERE A JENNIFER CON AMORE A LIVELLA A MEMORIA A NON DOMANDA RISPONDO A OCCHI CHIUSI A PASSO DI GAMBERO A PERDITA D' OCCHIO A PIEDI A PIEDI IN PIEMONTE A PIEDI IN PIEMONTE A PRECIPIZIO A PROPOS DE L' URSS A PROPOSITO DI TE A PROPOSITO DI UTE A RISCHIO A RISCHIO, GLI ETEROSESSUALI E L'AIDS A ROUTA LIBERA A SPASSO CON ANSELM A UN CERBIATTO SOMIGLIA IL MIO AMORE A UN CITTADINO CHE NON CREDE NELLA GIUSTIZIA ABBASSA IL TUO COLESTEROLO ABBI IL CORAGGIO DI CONOSCERE ABBIATE CORAGGIO ABC DEL COMUNISMO ABC DEL CORPO UMANO ABC DEL PC ABC DEL PC ABC DEL PC:COMPUTER TEST ABC DEL PC:DIZIONARIO DI INFORMATICA ABC DEL SUB ABISSO DEL PASSATO ABITATA DALLA MEMORIA ABORTO E CONTROLLO DELLE NASCITE ABRUZZO MOLISE ACCADDE UN' ESTATE ACHILLE PIE' VELOCE ACQUA DAL SOLE ADAMO EVA E IL SERPENTE ADDIO A QUESTI MONDI ADDIO ALLE ARMI ADDIO ALLE ARMI ADDIO DILETTA AMELIA ADDIO VECCHIO PIEMONTE ADRIATICO ADUA AEROBICA AEROMODELLISMO E RADIOCOMANDO AFRICO AFRICO AFRODITA AGENTE DELLA CIA AGGUATO SULL' ISOLA AGOSTINO AGOSTO 1914 AGRICOLTURA CAPITALISTICA E CLASSI SOCIALI IN ITALIA AGRITURISMO 2009 AGRITURISMO E VACANZE IN CAMPAGNA AGRITURISMO IN PIEMONTE AIUTO POIROT AIUTO POIROT! AL BUIO AL CAPONE AL CREPUSCOLO AL GIUDICE MIO ALBA NERA SU TOKYO ALBERGHI & RISTORANTI 2009 ALBERGHI E RISTORANTI D'ITALIA ALDOUS ALESSANDRO ALESSANDRO IN ASIA ALEXANDRE DUMAS ALFA & BETA ALGORITMI FONDAMENTALI ALGORITMI STRUTTURA DATI PROGRAMMI ALI D' ACCIAIO ALI SULL' OCEANO ALICE NEL PAESE DELLE MERAVIGLIE ALL' ANGELO DELLA CHIESA SCRIVI .. -

The Catholic Educator

The Catholic Educator Quarterly Journal of the Catholic Education Foundation Calendar Reminder: Virtual Annual Priests’ Seminar Zoom Meeting Format 4:00 pm July 14 to 4:00 pm July 16, 2020 For further information: call 215-327-5754 or email [email protected]. Volume 29 – Spring 2020 1 A Word From Our Editor “The Vocation of the Catholic School Teacher,” a reflection of the Reverend Peter M. J. Stravinskas, Ph.D., S.T.D., for a Lenten afternoon of recollection for the faculty of St. Gregory the Great School, Plantation, Florida, 4 March 2020. I want to suggest that an ideal passage on which Catholic school teachers would do well to reflect during Lent is Ezekiel 37, where the Prophet is confronted with a vision of a field of dry, dead bones and commanded to prophesy over them, so as to bring them back to life. Isn’t that the situation in which we find ourselves in the secularized West? Unfortunately, like the Chosen People of old, most of our contemporaries don’t realize that they are dead and that the culture is moribund. It is our task to demonstrate to them just how lifeless the whole culture is. Were it otherwise, how would one explain the vast array of children with learning disabilities of every kind; the couches of psychiatrists constantly filled; the suicide rate (especially among the young) the highest in our history? Too often, we Catholic educators have been intimidated into silence in the face of what is in reality an “anti-culture,” lest we appear “out of it” or “uncool.” Back in the silly – and stupid –Sixties, we were told that if we could shake off the shackles of religion and morality, we would experience true and complete happiness. -

Social Childbirth and Communities of Women in Early America Jocelyn Jessop

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Student research Student Work 2014 Social Childbirth and Communities of Women in Early America Jocelyn Jessop Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.depauw.edu/studentresearch Part of the United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Jessop, Jocelyn, "Social Childbirth and Communities of Women in Early America" (2014). Student research. Paper 14. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Social Childbirth and Communities of Women in Early America By: Jocelyn Jessop DePauw University Honor Scholar Senior Thesis, 2013-2014 Committee: David Gellman, Alicia Suarez, and Rebecca Upton 1 Introduction Social childbirth continued into the nineteenth century to be the primary occasion on which women expressed their love and care for one another and their mutual experience of life.1 Since the phrase first appeared in Richard W. Wertz and Dorothy C. Wertz’s, Lying-In: A History of Childbirth in America, social childbirth has become common vernacular in scholarly writings and the birthing world.2 Social childbirth created a space for communities of women to thrive. The communities served a very functional purpose, but more importantly, gave women an outlet in which to experience the trials and benefits of engaging with a community. Traditions of social childbirth continue today, but have evolved to fit the new needs of new generations.