THE MEDIEVAL CHURCH in SHETLAND: ORGANISATION and BUILDINGS Ronald G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 St Magnus Earl of Orkney

UHI Research Database pdf download summary Storyways Gibbon, Sarah Jane; Moore, James Published in: Open Archaeology Publication date: 2019 Publisher rights: © 2019 Sarah Jane Gibbon et al., published by De Gruyter. The re-use license for this item is: CC BY The Document Version you have downloaded here is: Peer reviewed version The final published version is available direct from the publisher website at: 10.1515/opar-2019-0016 Link to author version on UHI Research Database Citation for published version (APA): Gibbon, S. J., & Moore, J. (2019). Storyways: Visualising Saintly Impact in a North Atlantic Maritime Landscape. Open Archaeology, 5(1), 235-262. https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2019-0016 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights: 1) Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the UHI Research Database for the purpose of private study or research. 2) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 3) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 Open Archaeology 2019; 5: 235–262 Original Study Sarah Jane Gibbon*, James Moore Storyways: Visualising Saintly Impact in a North Atlantic Maritime Landscape https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2019-0016 Received February 28, 2019; accepted May 17, 2019 Abstract: This paper presents a new methodological approach and theorising framework which visualises intangible landscapes. -

Peerie Boat Week, Contributing Financially, and with Provision of the Main Venue and Key Staff

17th to 19th August Programme Peerie Boat Sponsored by Week organised by Shetland Amenity Trust Thank you! Shetland Amenity Trust are the lead organisation in the delivery of Peerie Boat Week, contributing financially, and with provision of the main venue and key staff. The Peerie Boat Week event would not be able to take place without the continued financial and practical support from sponsors, Serco NorthLink Ferries, Ocean Kinetics and Lerwick Port Authority. Volunteers also play a vital role in the delivery of the event programme and are a valuable part of the team. This includes those who train all summer learning to sail the Vaila Mae, and those who help with event delivery over the weekend. Serco NorthLink Ferries operate the lifeline ferry service between Shetland and the Scottish Mainland on a daily basis and support many local community teams and events. www.northlinkferries.co.uk Ocean Kinetics is at the forefront of engineering, with an extensive track record in fabrication, oil and gas, renewables, fishing and aquaculture, marine works and marine salvage. www.oceankinetics.co.uk Lerwick Port Authority manage Lerwick Harbour, the principal commercial port for Shetland and a key component in the islands’ economy. Lerwick Harbour is Britain’s “Top Port”. www.lerwick-harbour.co.uk Shetland Amenity Trust strives to protect, enhance and promote everything that is distinctive about Shetland’s heritage and culture. www.shetlandamenity.org Shetland Museum and Archives is a hub of discovery into Shetland’s history and it’s unique heritage and culture with an award winning dockside location. www.shetlandmuseumandarchives.org.uk www.facebook.com/shetlandboatweek 2 Book online - www.thelittleboxoffice.com/smaa Welcome to Peerie Boat Week 2018 Shetland Amenity Trust remains committed to celebrating Shetland’s maritime heritage. -

![{PDF EPUB} a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland by Noel Fojut a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.Com](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4988/pdf-epub-a-guide-to-prehistoric-and-viking-shetland-by-noel-fojut-a-guide-to-prehistoric-and-viking-shetland-fojut-noel-on-amazon-com-44988.webp)

{PDF EPUB} a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland by Noel Fojut a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.Com

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland by Noel Fojut A guide to prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. A guide to prehistoric and Viking Shetland4/5(1)A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland: Fojut, Noel ...https://www.amazon.com/Guide-Prehistoric-Shetland...A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking ShetlandAuthor: Noel FojutFormat: PaperbackVideos of A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland By Noel Fojut bing.com/videosWatch video on YouTube1:07Shetland’s Vikings take part in 'Up Helly Aa' fire festival14K viewsFeb 1, 2017YouTubeAFP News AgencyWatch video1:09Shetland holds Europe's largest Viking--themed fire festival195 viewsDailymotionWatch video on YouTube13:02Jarlshof - prehistoric and Norse settlement near Sumburgh, Shetland1.7K viewsNov 16, 2016YouTubeFarStriderWatch video on YouTube0:58Shetland's overrun by fire and Vikings...again! | BBC Newsbeat884 viewsJan 31, 2018YouTubeBBC NewsbeatWatch video on Mail Online0:56Vikings invade the Shetland Isles to celebrate in 2015Jan 28, 2015Mail OnlineJay AkbarSee more videos of A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland By Noel FojutA Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland - Noel Fojut ...https://books.google.com/books/about/A_guide_to...A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland: Author: Noel Fojut: Edition: 3, illustrated: Publisher: Shetland Times, 1994: ISBN: 0900662913, 9780900662911: Length: 127 pages : Export Citation:... FOJUT, Noel. A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland. ... A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland FOJUT, Noel. 0 ratings by Goodreads. ISBN 10: 0900662913 / ISBN 13: 9780900662911. Published by Shetland Times, 1994, 1994. -

Pictish Symbol Stones and Early Cross-Slabs from Orkney

Proc Soc Antiq Scot 144 (2014), PICTISH169–204 SYMBOL STONES AND EARLY CROSS-SLABS FROM ORKNEY | 169 Pictish symbol stones and early cross-slabs from Orkney Ian G Scott* and Anna Ritchie† ABSTRACT Orkney shared in the flowering of interest in stone carving that took place throughout Scotland from the 7th century AD onwards. The corpus illustrated here includes seven accomplished Pictish symbol- bearing stones, four small stones incised with rough versions of symbols, at least one relief-ornamented Pictish cross-slab, thirteen cross-slabs (including recumbent slabs), two portable cross-slabs and two pieces of church furniture in the form of an altar frontal and a portable altar slab. The art-historical context for this stone carving shows close links both with Shetland to the north and Caithness to the south, as well as more distant links with Iona and with the Pictish mainland south of the Moray Firth. The context and function of the stones are discussed and a case is made for the existence of an early monastery on the island of Flotta. While much has been written about the Picts only superb building stone but also ideal stone for and early Christianity in Orkney, illustration of carving, and is easily accessible on the foreshore the carved stones has mostly taken the form of and by quarrying. It fractures naturally into flat photographs and there is a clear need for a corpus rectilinear slabs, which are relatively soft and can of drawings of the stones in related scales in easily be incised, pecked or carved in relief. -

THE VIKINGS in ORKNEY James Graham-Campbell

THE VIKINGS IN ORKNEY James Graham-Campbell Introduction In recent years, it has been suggested that the first permanent Scandinavian presence in Orkney was not the result of forcible land-taking by Vikings, but came about instead through gradual penetration - a period which has been described as one of'informal' settlement (Morris 1985: 213; 1998: 83). Such would have involved a phase of co-existence, or even integration, between the native Picts and the earliest Norse settlers. This initial period, it is supposed, was then followed by 'a second, formal, settlement associated with the estab lishment of an earldom' (Morris 1998: 83 ), in the late 9'h century. The archaeological evidence advanced in support of the first 'period of overlap' is, however, open to alternative interpretation and, indeed, Alfred Smyth has com mented ( 1984: 145), in relation to the annalistic records of the earliest Viking attacks on Ireland, that these 'strongly suggest that the Norwegians did not gradually infiltrate the Northern Isles as farmers and fisherman and then sud denly tum nasty against their neighbours'. Others have supposed that the first phase of Norse settlement in Orkney would have involved, in the words of Buteux (1997: 263): 'ness-taking' (the fortifying of a headland by means of a cross-dyke) and the occupation of small off-shore islands. Crawford ( 1987: 46) argues that headland dykes on Orkney can be interpreted as indicating ness-taking. However many are equally likely to be prehistoric land boundaries, and no bases on either headlands or small islands have yet been positively identified. Buteux continues his discussion by observing, most pertinently, that: While this can not be taken as suggesting that such sites do not remain to be uncovered, the striking fact is that almost all identified Viking-period settlements in the Northern Isles are found overlying or immediately adjacent to sites which were occupied in the preceding Pictish period and which, furthermore, had frequently been settlements of some size and importance. -

Brough of Birsay Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC278 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90034) Taken into State care: 1933 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2004 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE BROUGH OF BIRSAY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office:Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office:Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH BROUGH OF BIRSAY BRIEF DESCRIPTION The monument comprises an area of Pictish to medieval settlement and ecclesiastical remains, situated on part of a small tidal island off the NW corner of Mainland Orkney. -

Northmavine the Laird’S Room at the Tangwick Haa Museum Tom Anderson

Northmavine The Laird’s room at the Tangwick Haa Museum Tom Anderson Tangwick Haa All aspects of life in Northmavine over the years are Northmavine The wilds of the North well illustrated in the displays at Tangwick Haa Museum at Eshaness. The Haa was built in the late 17th century for the Cheyne family, lairds of the Tangwick Estate and elsewhere in Shetland. Some Useful Information Johnnie Notions Accommodation: VisitShetland, Lerwick, John Williamson of Hamnavoe, known as Tel:01595 693434 Johnnie Notions for his inventive mind, was one of Braewick Caravan Park, Northmavine’s great characters. Though uneducated, Eshaness, Tel 01806 503345 he designed his own inoculation against smallpox, Neighbourhood saving thousands of local people from this 18th Information Point: Tangwick Haa Museum, Eshaness century scourge of Shetland, without losing a single Shops: Hillswick, Ollaberry patient. Fuel: Ollaberry Public Toilets: Hillswick, Ollaberry, Eshaness Tom Anderson Places to Eat: Hillswick, Eshaness Another famous son of Northmavine was Dr Tom Post Offices: Hillswick, Ollaberry Anderson MBE. A prolific composer of fiddle tunes Public Telephones: Sullom, Ollaberry, Leon, and a superb player, he is perhaps best remembered North Roe, Hillswick, Urafirth, for his work in teaching young fiddlers and for his role Eshaness in preserving Shetland’s musical heritage. He was Churches: Sullom, Hillswick, North Roe, awarded an honorary doctorate from Stirling Ollaberry University for his efforts in this field. Doctor: Hillswick, Tel: 01806 503277 Police Station: Brae, Tel: 01806 522381 The camping böd which now stands where Johnnie Notions once lived Contents copyright protected - please contact Shetland Amenity Trust for details. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the contents are accurate, the funding partners do not accept responsibility for any errors in this leaflet. -

The Arms of the Scottish Bishoprics

UC-NRLF B 2 7=13 fi57 BERKELEY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A \o Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/armsofscottishbiOOIyonrich /be R K E L E Y LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A h THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS. THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS BY Rev. W. T. LYON. M.A.. F.S.A. (Scot] WITH A FOREWORD BY The Most Revd. W. J. F. ROBBERDS, D.D.. Bishop of Brechin, and Primus of the Episcopal Church in Scotland. ILLUSTRATED BY A. C. CROLL MURRAY. Selkirk : The Scottish Chronicle" Offices. 1917. Co — V. PREFACE. The following chapters appeared in the pages of " The Scottish Chronicle " in 1915 and 1916, and it is owing to the courtesy of the Proprietor and Editor that they are now republished in book form. Their original publication in the pages of a Church newspaper will explain something of the lines on which the book is fashioned. The articles were written to explain and to describe the origin and de\elopment of the Armorial Bearings of the ancient Dioceses of Scotland. These Coats of arms are, and have been more or less con- tinuously, used by the Scottish Episcopal Church since they came into use in the middle of the 17th century, though whether the disestablished Church has a right to their use or not is a vexed question. Fox-Davies holds that the Church of Ireland and the Episcopal Chuich in Scotland lost their diocesan Coats of Arms on disestablishment, and that the Welsh Church will suffer the same loss when the Disestablishment Act comes into operation ( Public Arms). -

The Kirk in the Garden of Evie

THE KIRK IN THE GARDEN OF EVIE A Thumbnail Sketch of the History of the Church in Evie Trevor G Hunt Minister of the linked Churches of Evie, Firth and Rendall, Orkney First Published by Evie Kirk Session Evie, Orkney. 1987 Republished 1996 ComPrint, Orkney 908056 Forward to the 1987 Publication This brief history was compiled for the centenary of the present Evie Church building and I am indebted to all who have helped me in this work. I am especially indebted to the Kirk’s present Session Clerk, William Wood of Aikerness, who furnished useful local information, searched through old Session Minutes, and compiled the list of ministers for Appendix 3. Alastair Marwick of Whitemire, Clerk to the Board, supplied a good deal of literature, obtained a copy of the Title Deeds, gained access to the “Kirk aboon the Hill”, and conducted a tour (even across fields in his car) to various sites. He also contributed valuable local information and I am grateful for all his support. Thanks are also due to Margaret Halcro of Lower Crowrar, Rendall, for information about her name sake, and to the Moars of Crook, Rendall, for other Halcro family details. And to Sheila Lyon (Hestwall, Sandwick), who contributed information about Margaret Halcro (of the seventeenth century!). TREVOR G HUNT Finstown Manse March 1987 Foreword to the 1996 Publication Nearly ten years on seemed a good time to make this history available again, and to use the advances in computer technology to improve its appearance and to make one or two minor corrections.. I was also anxious to include the text of the history as a page on the Evie, Firth and Rendall Churches’ Internet site for reference and, since revision was necessary to do this, it was an opportunity to republish in printed form. -

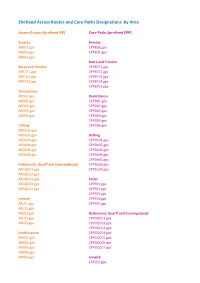

Shetland Access Routes and Core Paths Codes by Area

Shetland Access Routes and Core Paths Designations by Area Access Routes (prefixed AR) Core Paths (prefixed CPP) Bressay Bressay ARB01.gpx CPPB01.gpx ARB02.gpx CPPB02.gpx ARB03.gpx Burra and Trondra Burra and Trondra CPPBT01.gpx ARBT01.gpx CPPBT02.gpx ARBT02.gpx CPPBT03.gpx ARBT03.gpx CPPBT04.gpx CPPBT05.gpx Dunrossness ARD01.gpx Dunrossness ARD03.gpx CPPD01.gpx ARD04.gpx CPPD02.gpx ARD05.gpx CPPD03.gpx ARD06.gpx CPPD04.gpx CPPD05.gpx Delting CPPD06.gpx ARDe01.gpx ARDe02.gpx Delting ARDe03.gpx CPPDe01.gpx ARDe04.gpx CPPDe02.gpx ARDe06.gpx CPPDe03.gpx ARDe08.gpx CPPDe04.gpx CPPDe05.gpx Gulberwick, Quarff and Cunningsburgh CPPDe06.gpx ARGQC01.gpx CPPDe07.gpx ARGQC02.gpx ARGQC03.gpx Fetlar ARGQC04.gpx CPPF01.gpx ARGQC05.gpx CPPF02.gpx CPPF03.gpx Lerwick CPPF04.gpx ARL01.gpx CPPF05.gpx ARL02.gpx ARL03.gpx Gulberwick, Quarff and Cunningsburgh ARL04.gpx CPPGQC01.gpx ARL05.gpx CPPGQC02.gpx CPPGQC03.gpx Northmavine CPPGQC04.gpx ARN01.gpx CPPGQC05.gpx ARN02.gpx CPPGQC06.gpx ARN03.gpx CPPGQC07.gpx ARN04.gpx ARN05.gpx Lerwick CPPL01.gpx Nesting and Lunnasting CPPL02.gpx ARNL01.gpx CPPL03.gpx ARNL02.gpx CPPL04.gpx ARNL03.gpx CPPL05.gpx CPPL06.gpx Sandwick ARS01.gpx Northmavine ARS02.gpx CPPN01.gpx ARS03.gpx CPPN02.gpx ARS04.gpx CPPN03.gpx CPPN04.gpx Sandsting and Aithsting CPPN05.gpx ARSA04.gpx CPPN06.gpx ARSA05.gpx CPPN07.gpx ARSA07.gpx CPPN08.gpx ARSA10.gpx CPPN09.gpx CPPN10.gpx Scalloway CPPN11.gpx ARSC01.gpx CPPN12.gpx ARSC02.gpx CPPN13.gpx Skerries Nesting and Lunnasting ARSK01.gpx CPPNL01.gpx CPPNL03.gpx Tingwall, Whiteness and Weisdale CPPNL04.gpx -

Records of Species and Subspecies Recorded in Scotland on up to 20 Occasions

Records of species and subspecies recorded in Scotland on up to 20 occasions In 1993 SOC Council delegated to The Scottish Birds Records Committee (SBRC) responsibility for maintaining the Scottish List (list of all species and subspecies of wild birds recorded in Scotland). In turn, SBRC appointed a subcommittee to carry out this function. Current members are Dave Clugston, Ron Forrester, Angus Hogg, Bob McGowan Chris McInerny and Roger Riddington. In 1996, Peter Gordon and David Clugston, on behalf of SBRC, produced a list of records of species recorded in Scotland on up to 5 occasions (Gordon & Clugston 1996). Subsequently, SBRC decided to expand this list to include all acceptable records of species recorded on up to 20 occasions, and to incorporate subspecies with a similar number of records (Andrews & Naylor 2002). The last occasion that a complete list of records appeared in print was in The Birds of Scotland, which included all records up until 2004 (Forrester et al. 2007). During the period from 2002 until 2013, amendments and updates to the list of records appeared regularly as part of SBRC’s Scottish List Subcommittee’s reports in Scottish Birds. Since 2014 these records have appear on the SOC’s website, a significant advantage being that the entire list of all records for such species can be viewed together (Forrester 2014). The Scottish List Subcommittee are now updating the list annually. The current update includes records from the British Birds Rarities Committee’s Report on rare birds in Great Britain in 2015 (Hudson 2016) and SBRC’s Report on rare birds in Scotland, 2015 (McGowan & McInerny 2017). -

ST MAGNUS: an EXPLORATION of HIS SAINTHOOD William P

ST MAGNUS: AN EXPLORATION OF HIS SAINTHOOD William P. L. Thomson When the editors of New Dictionary of National Biography were recently discussing ways in which the new edition is different from the old, they re marked that one of the changes is in the treatment of saints: The lives [of saints] are no longer viewed as straightforward stories with an unfor tunate, but easily discounted, tendency to exaggeration, but may now be valued more for what they reveal about their authors, or about the milieu in which they were written, than for any information they contain about their ostensible subjects (DNB 1998). This is a good note on which to begin the exploration of Magnus's saint hood. We need to concern ourselves with the historical Magnus - and Magnus has a better historical basis than many saints - but equally we need to explore the ways people have perceived his sainthood and often manipulated it for their own purposes. The Divided Earldom The great Earl Thorfinn was dead by I 066 and his earldom was shared by his two sons (fig. I). It was a weakness of the earldom that it was divisible among heirs, and the joint rule of Paul and Erlend gave rise to a split which resulted not just in THOR FINN PAUL I ERLEND Kali I I HAKON MAGNUS Gunnhild m Kol I ,- I Maddad m Margaret HARALD PAUL II ROGNVALD E. of Atholl I HARALD MADDADSSON Ingirid I Harald the Younger Fig. 1. The Earls of Orkney. 46 the martyrdom of Magnus, but in feuds which still continued three and four generations later when Orkneyinga Saga was written (c.1200).