Tanksley Petition 2.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

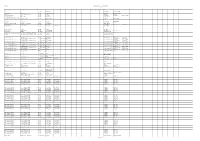

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Dixie Succumbs to Vision and Victory

sfltimes.com “Elevating the Dialogue” SERVING MIAMI-DADE, BROWARD, PALM BEACH AND MONROE COUNTIES FEBRUARY 5 — 11, 2015 | 50¢ IN THIS ISSUE PALM BEACH Dixie succumbs to vision By DAPHNE TAYLOR Special to South Florida Times Nearly every city in America and victory has a street named for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. And since Presi- dent Barack Obama made history BLACK HISTORY as the first black president of the SPECIAL SECTION/1D free world, he too, is gaining mo- mentum with streets named after Keeping our History him -- even right here in the Sun- Alive 365/24/7 shine State. But predominantly the idea about black Riviera Beach in Palm Beach a year ago. “I’ve al- County, is hoping to be among the ways had an idea to rename a lot of first where Barack Obama High- streets in our city. I think our city is way intersects with Dr. Martin Lu- much more than just a bunch of let- ther King Jr. Blvd. ters of the alphabet and numbers. It has an amazing ring to it I’ve wanted to rename our streets for Riviera Beach mayor, Bishop after African-American role mod- Thomas Masters, who is the brain els and leaders, so I had this idea behind renaming Old Dixie High- about the president for some way in Riviera Beach after the time now. It would be the right president. “It would be the father thing to do today and would and the son intersecting,” said reconnect this great city to Masters. “You have the father of history.” the Civil Rights Movement, and Masters said some crit- SOFLO LIVE you have the son, our first black ics said he should wait un- TARAJI HENSON/4C president, who benefitted from til after the leaders have that movement. -

DACIN SARA Repartitie Aferenta Trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU

DACIN SARA Repartitie aferenta trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 R10 R11 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 Greg Pruss - Gregory 13 13 2010 US Gela Babluani Gela Babluani Pruss 1000 post Terra After Earth 2013 US M. Night Shyamalan Gary Whitta M. Night Shyamalan 30 de nopti 30 Days of Night: Dark Days 2010 US Ben Ketai Ben Ketai Steve Niles 300-Eroii de la Termopile 300 2006 US Zack Snyder Kurt Johnstad Zack Snyder Michael B. Gordon 6 moduri de a muri 6 Ways to Die 2015 US Nadeem Soumah Nadeem Soumah 7 prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul / Sapte The Seven Little Foys 1955 US Melville Shavelson Jack Rose Melville Shavelson prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul A 25-a ora 25th Hour 2002 US Spike Lee David Benioff Elaine Goldsmith- A doua sansa Second Act 2018 US Peter Segal Justin Zackham Thomas A fost o data in Mexic-Desperado 2 Once Upon a Time in Mexico 2003 US Robert Rodriguez Robert Rodriguez A fost odata Curly Once Upon a Time 1944 US Alexander Hall Lewis Meltzer Oscar Saul Irving Fineman A naibii dragoste Crazy, Stupid, Love. 2011 US Glenn Ficarra John Requa Dan Fogelman Abandon - Puzzle psihologic Abandon 2002 US Stephen Gaghan Stephen Gaghan Acasa la coana mare 2 Big Momma's House 2 2006 US John Whitesell Don Rhymer Actiune de recuperare Extraction 2013 US Tony Giglio Tony Giglio Acum sunt 13 Ocean's Thirteen 2007 US Steven Soderbergh Brian Koppelman David Levien Acvila Legiunii a IX-a The Eagle 2011 GB/US Kevin Macdonald Jeremy Brock - ALCS Les aventures extraordinaires d'Adele Blanc- Adele Blanc Sec - Aventurile extraordinare Luc Besson - Sec - The Extraordinary Adventures of Adele 2010 FR/US Luc Besson - SACD/ALCS ale Adelei SACD/ALCS Blanc - Sec Adevarul despre criza Inside Job 2010 US Charles Ferguson Charles Ferguson Chad Beck Adam Bolt Adevarul gol-golut The Ugly Truth 2009 US Robert Luketic Karen McCullah Kirsten Smith Nicole Eastman Lebt wohl, Genossen - Kollaps (1990-1991) - CZ/DE/FR/HU Andrei Nekrasov - Gyoergy Dalos - VG. -

Shakespeare Unlimited: How King Lear Inspired Empire

Shakespeare Unlimited: How King Lear Inspired Empire Ilene Chaiken, Executive Producer Interviewed by Barbara Bogaev A Folger Shakespeare Library Podcast March 22, 2017 ---------------------------- MICHAEL WITMORE: Shakespeare can turn up almost anywhere. [A series of clips from Empire.] —How long you been plannin’ to kick my dad off the phone? —Since the day he banished me. I could die a thousand times… just please… From here on out, this is about to be the biggest, baddest company in hip-hop culture. Ladies and gentlemen, make some noise for the new era of Hakeem Lyon, y’all… MICHAEL: From the Folger Shakespeare Library, this is Shakespeare Unlimited. I‟m Michael Witmore, the Folger‟s director. This podcast is called “The World in Empire.” That clip you heard a second ago was from the Fox TV series Empire. The story of an aging ruler— in this case, the head of a hip-hop music dynasty—who sets his three children against each other. Sound familiar? As you will hear, from its very beginning, Empire has fashioned itself on the plot of King Lear. And that‟s not the only Shakespeare connection to the program. To explain all this, we brought in Empire’s showrunner, the woman who makes everything happen on time and on budget, Ilene Chaiken. She was interviewed by Barbara Bogaev. ---------------------------- BARBARA BOGAEV: Well, Empire seems as if its elevator pitch was a hip-hop King Lear. Was that the idea from the start? ILENE CHAIKEN: Yes, as I understand it, now I didn‟t create Empire— BOGAEV: Right, because you‟re the showrunner, and first there‟s a pilot, and then the series gets picked up, and then they pick the showrunner. -

Dossier De Presse TOUT SAVOIR SUR EMPIRE

DOSSIER DE PRESSE TOUT SAVOIR SUR EMPIRE DÉCOUVRIR LES PREMIÈRES IMAGES DE LA SAISON 1 SUCCESS STORY : Série dramatique n°1 de la saison 2014/15 aux USA Série n°2 de la saison 2014/15 aux USA, derrière Big Bang Theory sur CBS Meilleur score pour une nouvelle série aux USA depuis Desperate Housewives et Grey’s Anatomy en 2004-2005 Plus forte progression durant une première saison (+65%) depuis Docteur House en 2004 Série la plus tweetée avec 627 369 live tweets par épisode (devant The Walking Dead) SYNOPSIS Lucious Lyon (Terrence Howard, nominé aux lorsque son ex-femme, Cookie (Taraji P. Henson, Oscars et aux Golden Globes pour Hustle & nominée aux Oscars et aux Emmy Awards, Flow) est le roi du hip-hop. Ancien petit voyou, L’étrange histoire de Benjamin Button, Person son talent lui a permis de devenir un artiste of Interest), revient sept ans plus tôt que prévu, talentueux mais surtout le président d’Empire après presque 20 ans de détention. Audacieuse Entertainment. Pendant des années, son et sans scrupule, Cookie considère qu’elle s’est règne a été sans partage. Mais tout bascule sacrifiée pour que Lucious puisse démarrer sa lorsqu’il apprend qu’il est atteint d’une maladie carrière puis bâtir un empire, en vendant de la dégénérative. Il est désormais contraint de drogue. Trafic pour lequel elle a été envoyée transmettre à ses trois fils les clefs de son en prison. empire, sans faire éclater la cellule familiale déjà fragile. Pour le moment, Lucious reste à la tête d’Empire Entertainment. -

Media Analysis.Docx

Surname 1 Student’s Name Professor’s Name Course Date Media Analysis The first season of Empire drama series was premiered on Fox on January 7, 2015, and till March 18, 2015. The show was aired on Fox on Wednesdays at 9.00 PM ET (Fox, 2015). The 12 episodes American Television series, centers on an entertainment company, The Empire Entertainment Company. It is a family business making lots of profit from signing in popular musicians and hip-hop artists as well as recordings from talented family members. Each of the family members fights for control over the company. The main casts in the movie are a divorced couple Lucious Lyon and his ex-wife Cookie Lyon. The couple has three sons Andre (oldest son and married to Rhonda), Jamal (middle son), and Hakeem Lyon (Fox, 2015). Lucious and Cookie spent most of their early lives in drug dealing until Cookie was imprisoned. Although the family was living in poverty, they had ambitions to prosper in the music industry. They were a happy family always protecting and encouraging each other until Cookie was imprisoned (Fox, 2015). The interaction in the Empire Series is family-based. The ambitions and fight for control over The Empire Company bring the interactions in the family (IMDb, 2015). While in jail, the interaction between Cookie, Lucious, and their sons are minimal. After the release of Cookie from jail, her relationship with her ex-husband Lucious is business-centered until episode 7, where it becomes intimate (Fox, 2015). Although the divorced couple tries to keep their relationshipx-essays.com business-wise, it is clear Lucious loves Cookie. -

Popjustice, Volume 5

Acknowledgements The #PopJustice series of reports was produced by Liz Manne Strategy with generous support from Unbound Philanthropy and the Nathan Cummings Foundation. Revolutions Per Minute served as the project’s fiscal sponsor. Editorial Director: Liz Manne Senior Editor: Joseph Phelan Graphic Design: Luz Ortiz Cover Images: "POC TV Takeover" © 2015 Julio Salgado. All rights reserved. #PopJustice, Volume 5: Creative Voices & Professional Perspectives featuring René Balcer, Caty Borum Chattoo, Nato Green, Daryl Hannah, David Henry Hwang, Lorene Machado, Mik Moore, Karen Narasaki, Erin Potts, Mica Sigourney, Michael Skolnik, Tracy Van Slyke, Jeff Yang The views and opinions expressed in these reports are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Unbound Philanthropy, the Nathan Cummings Foundation, or Revolutions Per Minute. © 2016 Liz Manne Strategy Ltd. All rights reserved. Contents Page Introduction 4 1 Q&A with David Henry Hwang 5 2 Q&A with René Balcer 6 3 Q&A with Lorene Machado 7 4 Teaching Families Acceptance: An Appreciation of Empire 8 by Daryl Hannah 5 Diversity Doesn’t Happen Overnight 9 by Karen Narasaki 6 Reflections on Norman Lear 10 by Caty Borum Chattoo 7 How Athletes Breathe Life Into an Activist Movement 12 by Michael Skolnik 8 Changing Channels: “Peak TV” as an Expression of Establishment Privilege 13 by Jeff Yang 9 The Power of Micro-donations to Fund our Movements 15 by Erin Potts 10 What? A drag 16 by Mica Sigourney 11 Combating History Written With Lightning 18 by Mik Moore 12 Comedians vs. Landlords 19 by Nato Green 13 That’s so gay. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 11 RON NEWT, an individual, Case No. 15-cv-02778-CBM-JPRx 12 Plaintiff, 13 vs. ORDER [32,33,34,45,60,69] 14 TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX FILM 15 CORPORATION, et al., 16 Defendants. 17 18 The matters before the Court are: (1) Defendants Lee Daniels, Danny 19 Strong, Terrence Howard, and Malcolm Spellman’s (collectively, “Individual 20 Defendants’”) MotionDeadline to Dismiss First Amended Complaint with Prejudice 21 Pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) (Dkt. No. 32); (2) Defendant 22 Fox Broadcasting Company’s (“Fox’s”) Motion For Judgment on the Pleadings 23 (Dkt. No. 33); (3) Defendants’ Requests for Judicial Notice (Dkt. Nos. 34, 60); 24 and (4) Plaintiff’s Request for Judicial Notice (Dkt. No. 45). 25 I. FACTUAL AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND 26 The First Amended Complaint (“FAC”) asserts two causes of action against 27 the Individual Defendants and Fox (collectively, “Defendants”): (1) Copyright 28 Infringement, 17 U.S.C. §§ 101 et seq.; and (2) Breach of Implied-In-Fact 1 1 Contract. Plaintiff’s claims are based on Defendants’ alleged infringement and 2 use of Plaintiff’s Book, Screenplay, and DVD (each entitled “Bigger Than Big”) 3 in connection with the television series Empire. 4 II. STATEMENT OF THE LAW 5 A. Motion To Dismiss 6 Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) allows a court to dismiss a 7 complaint for “failure to state a claim upon which relief can be granted.” 8 Dismissal of a complaint can be based on either a lack of a cognizable legal theory 9 or the absence of sufficient facts alleged under a cognizable legal theory. -

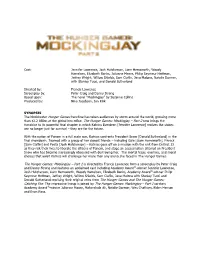

Catching Fire. the Impressive Lineup Is Joined by the Hunger Games

Cast: Jennifer Lawrence, Josh Hutcherson, Liam Hemsworth, Woody Harrelson, Elizabeth Banks, Julianne Moore, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Jeffrey Wright, Willow Shields, Sam Claflin, Jena Malone, Natalie Dormer, with Stanley Tucci, and Donald Sutherland Directed by: Francis Lawrence Screenplay by: Peter Craig and Danny Strong Based upon: The novel “Mockingjay” by Suzanne Collins Produced by: Nina Jacobson, Jon Kilik SYNOPSIS The blockbuster Hunger Games franchise has taken audiences by storm around the world, grossing more than $2.2 billion at the global box office. The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2 now brings the franchise to its powerful final chapter in which Katniss Everdeen [Jennifer Lawrence] realizes the stakes are no longer just for survival – they are for the future. With the nation of Panem in a full scale war, Katniss confronts President Snow [Donald Sutherland] in the final showdown. Teamed with a group of her closest friends – including Gale [Liam Hemsworth], Finnick [Sam Claflin] and Peeta [Josh Hutcherson] – Katniss goes off on a mission with the unit from District 13 as they risk their lives to liberate the citizens of Panem, and stage an assassination attempt on President Snow who has become increasingly obsessed with destroying her. The mortal traps, enemies, and moral choices that await Katniss will challenge her more than any arena she faced in The Hunger Games. The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2 is directed by Francis Lawrence from a screenplay by Peter Craig and Danny Strong and features an acclaimed cast including Academy Award®-winner Jennifer Lawrence, Josh Hutcherson, Liam Hemsworth, Woody Harrelson, Elizabeth Banks, Academy Award®-winner Philip Seymour Hoffman, Jeffrey Wright, Willow Shields, Sam Claflin, Jena Malone with Stanley Tucci and Donald Sutherland reprising their original roles from The Hunger Games and The Hunger Games: Catching Fire. -

3Rd Circ. Won't Revive Copyright Suit Over Fox's 'Empire' – Law360

3/18/2019 3rd Circ. Won't Revive Copyright Suit Over Fox's 'Empire' - Law360 Portfolio Media. Inc. | 111 West 19th Street, 5th floor | New York, NY 10011 | www.law360.com Phone: +1 646 783 7100 | Fax: +1 646 783 7161 | [email protected] 3rd Circ. Won't Revive Copyright Suit Over Fox's 'Empire' By Bonnie Eslinger Law360 (August 28, 2018, 11:24 PM EDT) -- The Third Circuit on Tuesday refused to revive a Philadelphia actor-turned-writer's copyright infringement suit accusing the creator of the Fox television drama "Empire" of poaching from his pitched pilot about an African-American record company owner, saying the two works weren't substantially similar. Clayton Prince Tanksley filed suit in January 2016 alleging that the creator of "Empire," Lee Daniels, expressed interest in his story idea at a 2008 Greater Philadelphia Film Office event where local writers pitched movie concepts to entertainment professionals. Tanksley said he provided Daniels with a DVD and a script of his proposed series, "Cream," which he wrote, directed and starred in. In 2015, nearly seven years later, Fox aired the debut episode of "Empire." The suit was tossed by a district court judge in April 2017. On Tuesday, the Third Circuit affirmed that decision. "We conclude that, superficial similarities notwithstanding, 'Cream' and 'Empire' are not substantially similar as a matter of law. This conclusion flows unavoidably from a comparison of the two shows' characters, settings and storylines," the federal appellate court stated. "As a preliminary matter, we note that the shared premise of the shows — an African-American, male record executive — is unprotectable. -

Branding the Iconic Ideals of Vivienne Westwood, Barack Obama, and Pope Francis

PUNK, OBAMACARE, AND A JESUIT: BRANDING THE ICONIC IDEALS OF VIVIENNE WESTWOOD, BARACK OBAMA, AND POPE FRANCIS AIDAN MOIR A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMMUNICATION & CULTURE YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO April 2021 © Aidan Moir, 2021 Abstract Practices of branding, promotion, and persona have become dominant influences structuring identity formation in popular culture. Creating an iconic brand identity is now an essential practice required for politicians, celebrities, global leaders, and other public figures to establish their image within a competitive media landscape shaped by consumer society. This dissertation analyzes the construction and circulation of Vivienne Westwood, Barack Obama, and Pope Francis as iconic brand identities in contemporary media and consumer culture. The content analysis and close textual analysis of select media coverage and other relevant material on key moments, events, and cultural texts associated with each figure deconstructs the media representation of Westwood, Obama, and Pope Francis. The brand identities of Westwood, Pope Francis, and Obama ultimately exhibit a unique form of iconic symbolic power, and exploring the complex dynamics shaping their public image demonstrates how they have achieved and maintained positions of authority. Although Westwood, Obama, and Pope Francis initially were each positioned as outsiders to the institutions of fashion, politics, and religion that they now represent, the media played a key role in mainstreaming their image for public consumption. Their iconic brand identities symbolize the influence of consumption in shaping how issues of public good circulate within public discourse, particularly in regard to the economy, health care, social inequality, and the environment. -

Arvold. Charlottesville, VA ● a Tlanta, GA 434.529.8442 404.626.1038

arvold. Charlottesville, VA ● A tlanta, GA 434.529.8442 404.626.1038 Erica Arvold, CSA CASTING DIRECTOR - FILM THE BLACK PHONE ( location CD) Dir: Scott Derrickson Blumhouse feature Prod: Jason Blum, Christopher Warner RED NOTICE (location CD) Dir: Rawson Marshall Thurber Netflix feature Prod: Beau Flynn, Dany Garcia, Hiram Garcia, Dwayne Johnson, Scott Sheldon FREAKY (location CD) Dir: Christopher Landon Blumhouse Productions feature Prod: Jason Blum, Adam Hendricks THE DAYLONG BROTHERS Dir: Brandon McCormick Triple Horse Studios feature Prod: Nicholas Kirk, Karl Horstmann, Rachel H. Allen BURDEN OF PROOF Dir: Cynthia Hill HBO Documentary Films Prod: Dawn Dreyer ∞ HARRIET ( location CD) Dir: Kasi Lemmons Stay Gold Features feature Prod: Debra Martin Chase, Daniela Taplin Lundberg, Shea Kammer CHARM CITY KINGS (location CD) Dir: Angel Manuel Soto Seven Heads Productions feature Prod: Marc Bienstock, Clarence Hammond, Caleeb Pinkett THE EVENING HOUR ( location CD) Dir: Braden King Secret Engine feature Prod: Lucas Joaquin, Derrick Tseng THE KING OF CRIMES Dir: Michael Duni The John Marshall Foundation feature Prod: Joni Albrecht, Christina Garnett THE GIANT (location CD) Dir: David Raboy Kudzu Enterprises feature Prod: Daniel Dewes, Rachael Fung, Clement Lepoutre MEDEA, SOUTH CAROLINA Dir: Daniel Wyland NextPix feature Prod: Don Thompson, Anne Clements JACQUELINE AND JILLY Dir: Victoria Rowell Days Ferry Productions feature Prod: Victoria Rowell, Jonathan Ortiz YES GOD YES (location CD) Dir: Karen Maine Vibe Productions feature Prod: Katie Cordeal, Colleen Hammond, Chris Columbus TEACHER’S PET Dir: Isaac Deitz Tub-O-Popcorn Productions feature Prod: Isaac Deitz A WRINKLE IN TIME (lead search) Dir: Ava DuVernay Walt Disney Pictures feature Casting Executive: Randi Hiller EPISODES Dir: Peter Hertsgaard Invizion Inc.