Examining the Representation of Empire's Cookie Lyon from A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Not for Publication United States Court of Appeals

NOT FOR PUBLICATION FILED AUG 28 2020 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS MOLLY C. DWYER, CLERK FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT U.S. COURT OF APPEALS EHM PRODUCTIONS, INC., DBA TMZ, a No. 19-55288 California corporation; WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT INC., a Delaware D.C. No. corporation, 2:16-cv-02001-SJO-GJS Plaintiffs-Appellees, MEMORANDUM* v. STARLINE TOURS OF HOLLYWOOD, INC., a California corporation, Defendant-Appellant. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California S. James Otero, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted August 10, 2020 Pasadena, California Before: WARDLAW and CLIFTON, Circuit Judges, and HILLMAN,** District Judge. Starline Tours of Hollywood, Inc. (Starline) appeals the district court’s * This disposition is not appropriate for publication and is not precedent except as provided by Ninth Circuit Rule 36-3. ** The Honorable Timothy Hillman, United States District Judge for the District of Massachusetts, sitting by designation. orders dismissing its First Amended Counterclaim (FACC) and denying its motion for leave to amend. We dismiss this appeal for lack of appellate jurisdiction. 1. Under 28 U.S.C. § 1291, the courts of appeals have jurisdiction over “final decisions of the district court.” Nat’l Distrib. Agency v. Nationwide Mut. Ins. Co., 117 F.3d 432, 433 (9th Cir. 1997). Generally, “a voluntary dismissal without prejudice is ordinarily not a final judgment from which the plaintiff may appeal.” Galaza v. Wolf, 954 F.3d 1267, 1270 (9th Cir. 2020) (cleaned up). A limited exception to this rule—which Starline seeks to invoke—permits an appeal “when a party that has suffered an adverse partial judgment subsequently dismisses its remaining claims without prejudice with the approval of the district court, and the record reveals no evidence of intent to manipulate our appellate jurisdiction.” James v. -

MOULDINGS | STAIR PARTS | BOARDS | EXTERIOR MILLWORK MIDWEST CHICAGO DISTRIBUTION CENTER Our Our STORY FAMILY DEEP ROOTS

MOULDINGS | STAIR PARTS | BOARDS | EXTERIOR MILLWORK MIDWEST CHICAGO DISTRIBUTION CENTER our our STORY FAMILY DEEP ROOTS. HIGH STANDARDS. BRIGHT FUTURE. EMPIRE IS NOW A PART OF THE NOVO FAMILY. Founded in 1946 Empire has grown into With a geographic footprint that touches Novo Building Products is the industry door shops, retail home centers, and one of the largest millwork distribution the majority of the eastern half of the leading manufacturer and distributor of millwork manufacturing partners and manufacturing companies in the United States, Empire is positioned for mouldings, stair parts, doors, and specialty throughout the United States and parts United States. continued expansion. building products. We are proud to serve of Canada and Mexico. LJ Smith building material dealers (lumberyards), Puyallup, WA L.J. Smith Learn more at . Salem, NH novobp.com Empire Zeeland, MI L.J. Smith Empire A llentown, PA Empire Bowerston, OH Channahon, IL L.J. Smith West Valley City, UT Empire REFRESH. Ornamental Mouldings Empire Archdale, NC Dallas, TX L.J. Smith Ball Ground, GA L.J. Smith Corona, CA Southwest Dallas, TX REVIVE. L.J. Smith Empire Houston, TX Lakeland, FL RENEW. 2 empireco.com | 800.253.9000 empireco.com | 800.253.9000 3 Style is individual, personal, and unique. Make your room a reflection of you... DISCOVER YOUR STYLE HERE Achieve a similar look using: P 450 Chair Rail | 041 Crown | 5030 Architrave | 312 Casing | L 163E Base Colonial, Ranch, Traditional, Midwestern, Early American, Inviting and Timeless... The new and improved Empireco.com. Explore our comprehensive collections of mouldings, Classic Classic Mouldings enhance any home style from Midwestern to stair parts, boards, and exterior millwork as well Early American, and blend perfectly with the classic style furnishing as find inspiration for every room in the home. -

Westcott Named Southwick Police Sergeant

TONIGhT: Chance of showers. Low of 64. Search for The Westfield News The WestfieldNews Search for“I TheT WestfieldIS THE NewsANONYMOUS Westfield350.com The WestfieldNews ‘THEY,’ THE ENIGMATIC Serving Westfield, Southwick, and surrounding Hilltowns ‘THEY“TIME’ WHOIS THE ARE ONLY IN CHARGE. WEATHER WHO ISCRITIC ‘THEY WITHOUT’? I DON ’T KNOW. TONIGHT NOBODYAMBITION KNOWS..” N OT EVEN Partly Cloudy. ‘JOHNTHEY STEINBECK’ THEMSELVES.” Low of 55. www.thewestfieldnews.com Search for The Westfield News Westfield350.comWestfield350.org The WestfieldNews — JOseph heLLer “TIME IS THE ONLY VOL. 86 NO. 151 Serving Westfield, Southwick, and surrounding Hilltowns WEATHER TUESDAY, JUNE 27, 2017 75 centsCRITIC WITHOUT VOL. 88 NO. 186 THURSDAY, AUGUST 8, 2019 75 Cents TONIGHT AMBITION.” Partly Cloudy. JOHN STEINBECK Low of 55. www.thewestfieldnews.com VOL. 86 NO. 151 WestcottTUESDAY, named JUNE 27, Southwick2017 Police sergeant 75 cents By HOPE E. TREMBLAY it.” Correspondent Westcott said he connects with residents SOUTHWICK – The Select Board this while off the clock, whether it’s at Big Y or week unanimously named Southwick on a ball field. Police K-9 officer Michael Westcott the “It’s my town,” he said. “I live here, I town’s new sergeant. grew up here, it’s where my family is from. Westcott, along with fellow officers I’ve traveled a lot and it’s always nice to Roger P. Arduini and Michael A. Taggert, come home.” The action heats up on the ice during the eighth interviewed for the position during a public When asked who he admires most, annual Kevin J. Major Memorial Hockey meeting of the board. -

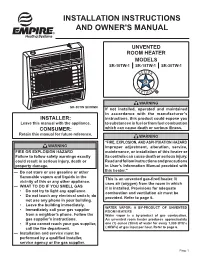

Installation INSTRUCTIONS and OWNER's MANUAL

Installation INSTRUCTIONS AND OWNER'S MANUAL UNVENTED ROOM HEATER MODELS SR-10TW-1 SR-18TW-1 SR-30TW-1 WARNING SR-30TW SHOWN If not installed, operated and maintained in accordance with the manufacturer’s INSTALLER: instructions, this product could expose you Leave this manual with the appliance. to substances in fuel or from fuel combustion CONSUMER: which can cause death or serious illness. Retain this manual for future reference. WARNING “FIRE, EXPLOSION, AND ASPHYXIATION HAZARD WARNING Improper adjustment, alteration, service, FIRE OR EXPLOSION HAZARD maintenance, or installation of this heater or Failure to follow safety warnings exactly its controls can cause death or serious injury. could result in serious injury, death or Read and follow instructions and precautions property damage. in User’s Information Manual provided with — Do not store or use gasoline or other this heater.” flammable vapors and liquids in the This is an unvented gas-fired heater. It vicinity of this or any other appliance. uses air (oxygen) from the room in which — WHAT TO DO IF YOU SMELL GAS it is installed. Provisions for adequate • Do not try to light any appliance. combustion and ventilation air must be • Do not touch any electrical switch; do provided. Refer to page 6. not use any phone in your building. • Leave the building immediately. WATER VAPOR: A BY-PRODUCT OF UNVENTED • Immediately call your gas supplier ROOM HEATERS from a neighbor’s phone. Follow the Water vapor is a by-product of gas combustion. gas supplier’s instructions. An unvented room heater produces approximately • If you cannot reach your gas supplier, one (1) ounce (30ml) of water for every 1,000 BTU’s call the fire department. -

From Disney to Disaster: the Disney Corporation’S Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks

From Disney to Disaster: The Disney Corporation’s Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks BY Kelsey N. Reese Spring 2021 WMNST 492W: Senior Capstone Seminar Dr. Jill Wood Reese 2 INTRODUCTION The popularized phrase “celebrity trainwreck” has taken off in the last ten years, and the phrase actively evokes specified images (Doyle, 2017). These images usually depict young women hounded by paparazzi cameras that are most likely drunk or high and half naked after a wild night of partying (Doyle, 2017). These girls then become the emblem of celebrity, bad girl femininity (Doyle, 2017; Kiefer, 2016). The trainwreck is always a woman and is usually subject to extra attention in the limelight (Doyle, 2017). Trainwrecks are in demand; almost everything they do becomes front page news, especially if their actions are seen as scandalous, defamatory, or insane. The exponential growth of the internet in the early 2000s created new avenues of interest in celebrity life, including that of social media, gossip blogs, online tabloids, and collections of paparazzi snapshots (Hamad & Taylor, 2015; Mercer, 2013). What resulted was 24/7 media access into the trainwreck’s life and their long line of outrageous, commiserable actions (Doyle, 2017). Kristy Fairclough coined the term trainwreck in 2008 as a way to describe young, wild female celebrities who exemplify the ‘good girl gone bad’ image (Fairclough, 2008; Goodin-Smith, 2014). While the coining of the term is rather recent, the trainwreck image itself is not; in their book titled Trainwreck, Jude Ellison Doyle postulates that the trainwreck classification dates back to feminism’s first wave with Mary Wollstonecraft (Anand, 2018; Doyle, 2017). -

Rap and Feng Shui: on Ass Politics, Cultural Studies, and the Timbaland Sound

Chapter 25 Rap and Feng Shui: On Ass Politics, Cultural Studies, and the Timbaland Sound Jason King ? (body and soul ± a beginning . Buttocks date from remotest antiquity. They appeared when men conceived the idea of standing up on their hind legs and remaining there ± a crucial moment in our evolution since the buttock muscles then underwent considerable development . At the same time their hands were freed and the engagement of the skull on the spinal column was modified, which allowed the brain to develop. Let us remember this interesting idea: man's buttocks were possibly, in some way, responsible for the early emergence of his brain. Jean-Luc Hennig the starting point for this essayis the black ass. (buttocks, behind, rump, arse, derriere ± what you will) like mymother would tell me ± get your black ass in here! The vulgar ass, the sanctified ass. The black ass ± whipped, chained, beaten, punished, set free. territorialized, stolen, sexualized, exercised. the ass ± a marker of racial identity, a stereotype, property, possession. pleasure/terror. liberation/ entrapment.1 the ass ± entrance, exit. revolving door. hottentot venus. abner louima. jiggly, scrawny. protrusion/orifice.2 penetrable/impenetrable. masculine/feminine. waste, shit, excess. the sublime, beautiful. round, circular, (w)hole. The ass (w)hole) ± wholeness, hol(e)y-ness. the seat of the soul. the funky black ass.3 the black ass (is a) (as a) drum. The ass is a highlycontested and deeplyambivalent site/sight . It maybe a nexus, even, for the unfolding of contemporaryculture and politics. It becomes useful to think about the ass in terms of metaphor ± the ass, and the asshole, as the ``dirty'' (open) secret, the entrance and the exit, the back door of cultural and sexual politics. -

Black Women, Natural Hair, and New Media (Re)Negotiations of Beauty

“IT’S THE FEELINGS I WEAR”: BLACK WOMEN, NATURAL HAIR, AND NEW MEDIA (RE)NEGOTIATIONS OF BEAUTY By Kristin Denise Rowe A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of African American and African Studies—Doctor of Philosophy 2019 ABSTRACT “IT’S THE FEELINGS I WEAR”: BLACK WOMEN, NATURAL HAIR, AND NEW MEDIA (RE)NEGOTIATIONS OF BEAUTY By Kristin Denise Rowe At the intersection of social media, a trend in organic products, and an interest in do-it-yourself culture, the late 2000s opened a space for many Black American women to stop chemically straightening their hair via “relaxers” and begin to wear their hair natural—resulting in an Internet-based cultural phenomenon known as the “natural hair movement.” Within this context, conversations around beauty standards, hair politics, and Black women’s embodiment have flourished within the public sphere, largely through YouTube, social media, and websites. My project maps these conversations, by exploring contemporary expressions of Black women’s natural hair within cultural production. Using textual and content analysis, I investigate various sites of inquiry: natural hair product advertisements and internet representations, as well as the ways hair texture is evoked in recent song lyrics, filmic scenes, and non- fiction prose by Black women. Each of these “hair moments” offers a complex articulation of the ways Black women experience, share, and negotiate the socio-historically fraught terrain that is racialized body politics -

BOARDWALK EMPIRE "In God We Trust" by Reginald Beltran Based

BOARDWALK EMPIRE "In God We Trust" By Reginald Beltran Based on characters by Terence Winter Reginald Beltran [email protected] FADE IN: EXT. FOREST - DAY A DEAD DOE lies on the floor. Blood oozes out of a fatal bullet wound on its side. Its open, unblinking eyes stare ahead. The rustling sound of leaves. The fresh blood attracts the attention of a hungry BEAR. It approaches the lifeless doe, and claims the kill for itself. The bear licks the fresh blood on the ground. More rustling of the undergrowth. The bear looks up and sees RICHARD HARROW, armed with a rifle, pushing past a thicket of trees and branches. For a moment, the two experienced killers stare at each other with unblinking eyes. One set belongs to a primal predator and the other set is half man, half mask. The bear stands on its two feet. It ROARS at its competitor. Richard readies his rifle for a shot, but the rifle is jammed. The bear charges. Calmly, Richard drops to one knee, examines the rifle and fixes the jam. He doesn’t miss a beat. He steadies the rifle and aims it. BANG! It’s a sniper’s mark. The bear drops to the ground immediately with a sickening THUD. Blood oozes out of a gunshot wound just under its eyes - the Richard Harrow special. EXT. FOREST - NIGHT Even with a full moon, light is sparse in these woods. Only a campfire provide sufficient light and warmth for Richard. A spit has been prepared over the fire. A skinned and gutted doe lies beside the campfire. -

Lee Daniels on Empire: the Show Has Already Changed Homophobes' Minds

8/15/2018 Empire on Fox: Lee Daniels on his Show's Effect on Homophobia | Time Lee Daniels on Empire: The Show Has Already Changed Homophobes' Minds Lee Daniels on Dec. 1, 2014 in New York City. Theo Warg—Getty Images / IFP By LILY ROTHMAN January 7, 2015 Lee Daniels is best known as the lmmaker behind gritty independent lms like Precious, but his new project is the slick primetime drama Empire, premiering Jan. 7 on Fox, which he co-created with Danny Strong. Daniels recently spoke to TIME about the show, and how — despite not being independently made — http://time.com/3656583/lee-daniels-empire/ 1/3 8/15/2018 Empire on Fox: Lee Daniels on his Show's Effect on Homophobia | Time it’s a personal story. The Shakespeare-inected tale of record mogul Lucious Lyon (Terrence Howard), his ex-wife Cookie (Taraji P. Henson) and their sons Andre, Jamal and Hakeem, often draws on stories from his own life. And, he tells TIME, the show is already making a difference toward his larger aim of increasing tolerance among its audience: TIME: You’ve told a story about trying on your mother’s shoes as a child. There’s a scene in the Empire pilot that sounds very similar to that episode, where Lucious reacts to seeing his young son do just that… Lee Daniels: I was terried of that scene. My sister was an extra — she’s in the scene — and when the kid put the shoes on, having him walk in front of his father, I had a meltdown. -

Shakespeare Unlimited: How King Lear Inspired Empire

Shakespeare Unlimited: How King Lear Inspired Empire Ilene Chaiken, Executive Producer Interviewed by Barbara Bogaev A Folger Shakespeare Library Podcast March 22, 2017 ---------------------------- MICHAEL WITMORE: Shakespeare can turn up almost anywhere. [A series of clips from Empire.] —How long you been plannin’ to kick my dad off the phone? —Since the day he banished me. I could die a thousand times… just please… From here on out, this is about to be the biggest, baddest company in hip-hop culture. Ladies and gentlemen, make some noise for the new era of Hakeem Lyon, y’all… MICHAEL: From the Folger Shakespeare Library, this is Shakespeare Unlimited. I‟m Michael Witmore, the Folger‟s director. This podcast is called “The World in Empire.” That clip you heard a second ago was from the Fox TV series Empire. The story of an aging ruler— in this case, the head of a hip-hop music dynasty—who sets his three children against each other. Sound familiar? As you will hear, from its very beginning, Empire has fashioned itself on the plot of King Lear. And that‟s not the only Shakespeare connection to the program. To explain all this, we brought in Empire’s showrunner, the woman who makes everything happen on time and on budget, Ilene Chaiken. She was interviewed by Barbara Bogaev. ---------------------------- BARBARA BOGAEV: Well, Empire seems as if its elevator pitch was a hip-hop King Lear. Was that the idea from the start? ILENE CHAIKEN: Yes, as I understand it, now I didn‟t create Empire— BOGAEV: Right, because you‟re the showrunner, and first there‟s a pilot, and then the series gets picked up, and then they pick the showrunner. -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

Hergé and Tintin

Hergé and Tintin PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Fri, 20 Jan 2012 15:32:26 UTC Contents Articles Hergé 1 Hergé 1 The Adventures of Tintin 11 The Adventures of Tintin 11 Tintin in the Land of the Soviets 30 Tintin in the Congo 37 Tintin in America 44 Cigars of the Pharaoh 47 The Blue Lotus 53 The Broken Ear 58 The Black Island 63 King Ottokar's Sceptre 68 The Crab with the Golden Claws 73 The Shooting Star 76 The Secret of the Unicorn 80 Red Rackham's Treasure 85 The Seven Crystal Balls 90 Prisoners of the Sun 94 Land of Black Gold 97 Destination Moon 102 Explorers on the Moon 105 The Calculus Affair 110 The Red Sea Sharks 114 Tintin in Tibet 118 The Castafiore Emerald 124 Flight 714 126 Tintin and the Picaros 129 Tintin and Alph-Art 132 Publications of Tintin 137 Le Petit Vingtième 137 Le Soir 140 Tintin magazine 141 Casterman 146 Methuen Publishing 147 Tintin characters 150 List of characters 150 Captain Haddock 170 Professor Calculus 173 Thomson and Thompson 177 Rastapopoulos 180 Bianca Castafiore 182 Chang Chong-Chen 184 Nestor 187 Locations in Tintin 188 Settings in The Adventures of Tintin 188 Borduria 192 Bordurian 194 Marlinspike Hall 196 San Theodoros 198 Syldavia 202 Syldavian 207 Tintin in other media 212 Tintin books, films, and media 212 Tintin on postage stamps 216 Tintin coins 217 Books featuring Tintin 218 Tintin's Travel Diaries 218 Tintin television series 219 Hergé's Adventures of Tintin 219 The Adventures of Tintin 222 Tintin films