Redalyc.SUGAR, EMPIRE, and REVOLUTION in EASTERN CUBA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Not for Publication United States Court of Appeals

NOT FOR PUBLICATION FILED AUG 28 2020 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS MOLLY C. DWYER, CLERK FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT U.S. COURT OF APPEALS EHM PRODUCTIONS, INC., DBA TMZ, a No. 19-55288 California corporation; WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT INC., a Delaware D.C. No. corporation, 2:16-cv-02001-SJO-GJS Plaintiffs-Appellees, MEMORANDUM* v. STARLINE TOURS OF HOLLYWOOD, INC., a California corporation, Defendant-Appellant. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California S. James Otero, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted August 10, 2020 Pasadena, California Before: WARDLAW and CLIFTON, Circuit Judges, and HILLMAN,** District Judge. Starline Tours of Hollywood, Inc. (Starline) appeals the district court’s * This disposition is not appropriate for publication and is not precedent except as provided by Ninth Circuit Rule 36-3. ** The Honorable Timothy Hillman, United States District Judge for the District of Massachusetts, sitting by designation. orders dismissing its First Amended Counterclaim (FACC) and denying its motion for leave to amend. We dismiss this appeal for lack of appellate jurisdiction. 1. Under 28 U.S.C. § 1291, the courts of appeals have jurisdiction over “final decisions of the district court.” Nat’l Distrib. Agency v. Nationwide Mut. Ins. Co., 117 F.3d 432, 433 (9th Cir. 1997). Generally, “a voluntary dismissal without prejudice is ordinarily not a final judgment from which the plaintiff may appeal.” Galaza v. Wolf, 954 F.3d 1267, 1270 (9th Cir. 2020) (cleaned up). A limited exception to this rule—which Starline seeks to invoke—permits an appeal “when a party that has suffered an adverse partial judgment subsequently dismisses its remaining claims without prejudice with the approval of the district court, and the record reveals no evidence of intent to manipulate our appellate jurisdiction.” James v. -

Overview Print Page Close Window

World Directory of Minorities Americas MRG Directory –> Cuba –> Cuba Overview Print Page Close Window Cuba Overview Environment Peoples History Governance Current state of minorities and indigenous peoples Environment Cuba is the largest island in the Caribbean. It is located 150 kilometres south of the tip of the US state of Florida and east of the Yucatán Peninsula. On the east, Cuba is separated by the Windward Passage from Hispaniola, the island shared by Haiti and Dominican Republic. The total land area is 114,524 sq km, which includes the Isla de la Juventud (formerly called Isle of Pines) and other small adjacent islands. Peoples Main languages: Spanish Main religions: Christianity (Roman Catholic, Protestant), syncretic African religions The majority of the population of Cuba is 51% mulatto (mixed white and black), 37% white, 11% black and 1% Chinese (CIA, 2001). However, according to the Official 2002 Cuba Census, 65% of the population is white, 10% black and 25% mulatto. Although there are no distinct indigenous communities still in existence, some mixed but recognizably indigenous Ciboney-Taino-Arawak-descended populations are still considered to have survived in parts of rural Cuba. Furthermore the indigenous element is still in evidence, interwoven as part of the overall population's cultural and genetic heritage. There is no expatriate immigrant population. More than 75 per cent of the population is classified as urban. The revolutionary government, installed in 1959, has generally destroyed the rigid social stratification inherited from Spanish colonial rule. During Spanish colonial rule (and later under US influence) Cuba was a major sugar-producing territory. -

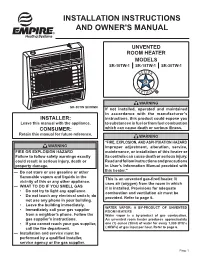

Installation INSTRUCTIONS and OWNER's MANUAL

Installation INSTRUCTIONS AND OWNER'S MANUAL UNVENTED ROOM HEATER MODELS SR-10TW-1 SR-18TW-1 SR-30TW-1 WARNING SR-30TW SHOWN If not installed, operated and maintained in accordance with the manufacturer’s INSTALLER: instructions, this product could expose you Leave this manual with the appliance. to substances in fuel or from fuel combustion CONSUMER: which can cause death or serious illness. Retain this manual for future reference. WARNING “FIRE, EXPLOSION, AND ASPHYXIATION HAZARD WARNING Improper adjustment, alteration, service, FIRE OR EXPLOSION HAZARD maintenance, or installation of this heater or Failure to follow safety warnings exactly its controls can cause death or serious injury. could result in serious injury, death or Read and follow instructions and precautions property damage. in User’s Information Manual provided with — Do not store or use gasoline or other this heater.” flammable vapors and liquids in the This is an unvented gas-fired heater. It vicinity of this or any other appliance. uses air (oxygen) from the room in which — WHAT TO DO IF YOU SMELL GAS it is installed. Provisions for adequate • Do not try to light any appliance. combustion and ventilation air must be • Do not touch any electrical switch; do provided. Refer to page 6. not use any phone in your building. • Leave the building immediately. WATER VAPOR: A BY-PRODUCT OF UNVENTED • Immediately call your gas supplier ROOM HEATERS from a neighbor’s phone. Follow the Water vapor is a by-product of gas combustion. gas supplier’s instructions. An unvented room heater produces approximately • If you cannot reach your gas supplier, one (1) ounce (30ml) of water for every 1,000 BTU’s call the fire department. -

Report of Summer Activities for TCD Research Grant Anmari Alvarez

Report of Summer Activities for TCD Research Grant Anmari Alvarez Aleman Research and conservation of Antillean manatee in the east of Cuba. The research activities developed during May-August, 2016 were developed with the goal to strengthen the research project developed to understand the conservation status of Antillean manatees in Cuba. Some of the research effort were implemented in the east of Cuba with the purpose of gather new samples, data and information about manatees and its interaction with fisherman in this part of the country. We separated our work in two phases. The first was a scoping trip to the east of Cuba with the purpose of meet and talk with coast guards, forest guards, fishermen, and key persons in these coastal communities in order to get them involved with the stranding and sighting network in Cuba. During the second phase we continued a monitoring program started in the Isle of Youth in 2010 with the goal of understand important ecological aspects of manatees. During this trip we developed boat surveys, habitat assessments and the manatee captures and tagging program. Phase 1: Scoping trip, May 2016 During the trip we collected information about manatee presence and interaction with fisheries in the north east part of Cuban archipelago and also collected samples for genetic studies. During the trip we visited fishing ports and protected areas in Villa Clara, Sancti Spiritus, Ciego de Avila, Camaguey, Las Tunas, Holguin, Baracoa and Santiago de Cuba. The visited institutions and areas were (Figure 1): 1. Nazabal Bay, Villa Clara. Biological station of the Fauna Refuge and private fishery port. -

Shakespeare Unlimited: How King Lear Inspired Empire

Shakespeare Unlimited: How King Lear Inspired Empire Ilene Chaiken, Executive Producer Interviewed by Barbara Bogaev A Folger Shakespeare Library Podcast March 22, 2017 ---------------------------- MICHAEL WITMORE: Shakespeare can turn up almost anywhere. [A series of clips from Empire.] —How long you been plannin’ to kick my dad off the phone? —Since the day he banished me. I could die a thousand times… just please… From here on out, this is about to be the biggest, baddest company in hip-hop culture. Ladies and gentlemen, make some noise for the new era of Hakeem Lyon, y’all… MICHAEL: From the Folger Shakespeare Library, this is Shakespeare Unlimited. I‟m Michael Witmore, the Folger‟s director. This podcast is called “The World in Empire.” That clip you heard a second ago was from the Fox TV series Empire. The story of an aging ruler— in this case, the head of a hip-hop music dynasty—who sets his three children against each other. Sound familiar? As you will hear, from its very beginning, Empire has fashioned itself on the plot of King Lear. And that‟s not the only Shakespeare connection to the program. To explain all this, we brought in Empire’s showrunner, the woman who makes everything happen on time and on budget, Ilene Chaiken. She was interviewed by Barbara Bogaev. ---------------------------- BARBARA BOGAEV: Well, Empire seems as if its elevator pitch was a hip-hop King Lear. Was that the idea from the start? ILENE CHAIKEN: Yes, as I understand it, now I didn‟t create Empire— BOGAEV: Right, because you‟re the showrunner, and first there‟s a pilot, and then the series gets picked up, and then they pick the showrunner. -

Oriente Province Begin

• Inter - American News ¦p a p-M Member Inter American wHk mb I Press Association for English - • Speaking people For Liberty, Culture and Daily Hemispheric Solidarity he for a better understanding between the T Americas 4th YEAR MIAMI SPRINGS, FLA., SUNDAY, JUNE 2, 1957 NUMBER 271 G. A. SAN ROMAN C. W. SMITH S. SMITH President Vice President Vice President Nicaragua FRANCISCO AGUIRRE HORACIO AGUIRRE and Vice President and Publisher Vice President Editor and Manager Sen. Smathers Proposes Antonio Ruiz Fred M. Shaver Eliseo Riera-G6mez Large Scale Operations Managing Editor Business Manager Advt. Si Clre. Mgr. Honduras Agree Published daily except Monday Entered as second class matter at the Amendment to Provide a Post Office of Miami Springs. Fla., on February 8. 1956. Against Cuban Rebels in EDITORIAL Fund for Latin America to Avoid Use U.S. CONSULAR SERVICE IN LATIN AMERICA WASHINGTON The Senator from Florida, George Smathers of Violence The existing restrictions and requirements regarding (Democrat), this week proposed an Oriente Province Begin visas for residents and tourists wishing to travel to the amendment to the Mutual Secur- GUATEMALA, June HUP) United States have complicated, no doubt, the functions of ity Authorization Bill which would Honduras and Nicaragua agreed to the consulates of this country in the whole world. provide for a $25 million economic a solution of their territorial con- BATISTA DENIES Cuban Leader Ready to Participate development fund for Latin Ame- flict without the use of violence, For Latin America the -

Continuaron Aumentando Las Temperaturas Y Se Mantienen Escasas Las Lluvias En Todo El Pais

ISSN 1029-2055 BOLETÍN AGROMETEOROLÓGICO NACIONAL MINISTERIO DE CIENCIA, TECNOLOGÍA Y MEDIO AMBIENTE INSTITUTO DE METEOROLOGÍA Vol. 27 No. 14 2DA DÉCADA MAYO 2008 CONTENIDO: Condiciones Meteorológicas Condiciones Agrometeorológicas Apicultura Avicultura Arroz Café y Cacao Caña de Azúcar Cítricos y Frutales Cultivos Varios Ganadería Tabaco Perspectivas Meteorológicas Fases de la Luna CONTINUARON AUMENTANDO LAS TEMPERATURAS Y SE MANTIENEN ESCASAS LAS LLUVIAS EN TODO EL PAIS. SE ESPERA POCO CAMBIO EN LAS CONDICIONES DEL TIEMPO. 2da. déc. de Mayo 2008 CONDICIONES METEOROLÓGICAS DE LA 1RA DÉCADA DE MAYO ABASTECIMIENTO DE CALOR Las temperaturas medias del aire aumentaron de forma significativa en relación con la década anterior y con respecto a la norma (más de 1,0 °C, como promedio en todo el país); siendo también superiores a las registradas en igual período del año anterior. Las temperaturas máximas y mínimas medias del aire ascendieron notablemente en relación con la década anterior, oscilando entre 32,5 y 33,0 °C y entre 21,8 y 22,4 °C como promedio, respectivamente, en todo el territorio nacional. COMPORTAMIENTO DE LA TEMPERATURA DEL AIRE POR REGIONES Desviación con respecto a: Regiones Temp. Media (°C) Norma Déc. Anterior Déc. año anterior Occidental 27,4 +1,4 +1,4 +1,6 Central 27,2 +0,9 +1,0 +0,8 Oriental 27,7 +1,2 +0,9 +0,6 I. de la Juventud 27,7 +1,2 +1,2 +1,5 Nota: + Valores por encima - Valores por debajo - Región Occidental: Desde la provincia Pinar del Río hasta Matanzas. - Región Central: Desde la provincia de Cienfuegos hasta Camagüey. -

Highlights Situation Overview

Response to Hurricane Irma: Cuba Situation Report No. 1. Office of the Resident Coordinator ( 07/09/ 20176) This report is produced by the Office of the Resident Coordinator. It covers the period from 20:00 hrs. on September 06th to 14:00 hrs. on September 07th.The next report will be issued on or around 08/09. Highlights Category 5 Hurricane Irma, the fifth strongest Atlantic hurricane on record, will hit Cuba in the coming hours. Cuba has declared the Hurricane Alarm Phase today in seven provinces in the country, with 5.2 million people (46% of the Cuban population) affected. More than 1,130,000 people (10% of the Cuban population) are expected to be evacuated to protection centers or houses of neighbors or relatives. Beginning this evening, heavy waves are forecasted in the eastern part of the country, causing coastal flooding on the northern shores of Guantánamo and Holguín Provinces. 1,130,000 + 600 1,031 people Tons of pregnant evacuated food secured women protected Situation overview Heavy tidal waves that accompany Hurricane Irma, a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, began to affect the northern coast of Cuba’s eastern provinces today, 7 September. With maximum sustained winds exceeding 252 kilometers (km) per hour, the hurricane is advancing through the Caribbean waters under favorable atmospheric conditions that could contribute to its intensification. According to the Forecast Center of the National Institute of Meteorology (Insmet), Hurricane Irma will impact the eastern part of Cuba in the early hours of Friday, 8 September, and continue its trajectory along the northern coast to the Central Region, where it is expected to make a shift to the north and continue moving towards Florida. -

Matthew J. Blevins, Vice President, Empire Stock Transfer Inc

\JHf Empire Stock Transfer Inc. 1859 Whitney Mesa Dr. Henderson, NV 89014 KECEIVED January 15,2014 JAN 16 2014 Elizabeth M. Murphy OFFICbOHHESFrpcTi.gg Secretary U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 100 F Street, NE Washington, DC 20549 Dear Ms. Murphy: Today I am responding on behalf of Empire Stock Transfer Inc. with respect to the Securities and Exchange Commission's Crowdfunding rule proposal, Release Nos. 33-9470; 34-70741; File No. S7-09-13. " The Securities and Exchange Commission, the "Commission", is proposing for comment new Regulation Crowdfunding under the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 to implement the requirements of Title III of the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act. Regulation Crowdfunding would prescribe rules governing the offer and sale of securities under new Section 4(a)(6) ofthe Securities Act of 1933. The proposal also would provide a framework for the regulation of registered funding portals and brokers that issuers are required to use as intermediaries in the offer and sale of securities in reliance on Section 4(a)(6). In addition, the proposal would exempt securities sold pursuant to Section 4(a)(6) from the registration requirements ofSection 12(g) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Empire Stock Transfer Inc., "Empire", is a stock transfer agent with operations in the United States. Our clients, whom are primarily small-cap issuers, are located throughout the world. Empire assists private startups as well as publicly-traded companies in their efforts to maintain a compliant and healthy shareholder relationship. How does the Commission view a transfer agent? http://www.sec.gov/divisions/marketreg/mrtransfer.shtml Transfer agents record changes of ownership, maintain the issuer's security holder records, cancel and issue certificates, and distribute dividends. -

BT TM-15 Manual.Pdf

BT_TM-15_Manual.qxp 6/17/09 5:23 PM Page C OWNER’S MANUAL BTPAINTBALL.COM BT_TM-15_Manual.qxp 6/17/09 5:23 PM Page D CONTENTS Page 1. Rules for Safe Marker Handling 1 2. Introduction and Specifications 1 3. Battery Replacement and Life Indicator 1 4. Compressed Air/Nitrogen Supply 2 5. Basic Operation 2 6. Firing the TM-15 4 7. Break Beam Eyes Operation 4 8. Unloading the TM-15 5 9. Regulator and Velocity Adjustments 5 10. Programming 6 11. Setting Functions 7 12. Trigger Adjustments 9 13. General Maintenance 10 14. Assembly/Disassembly Instructions 11 15. Storage and Transportation 14 16. Troubleshooting Guide 14 For manuals and warranty details, go to: 17. Diagrams and Parts List 17 paintballsolutions.com WARRANTY (Inside Back Cover) For manuals in other languages, (where appli- cable), go to:paintballsolutions.com ©2009 BT Paintball Designs, Inc. The BT Shield, “Battle Tested” and “TM-15” are trademarks of NEITHER BT PAINTBALL DESIGNS, INC. NOR ANY OF ITS PRODUCTS ARE AFFILIATED WITH TIPPMANN SPORTS, LLC. BT Paintball Designs, Inc. All rights reserved. BTPAINTBALL.COM BT_TM-15_Manual.qxp 6/17/09 5:23 PM Page 1 1. Rules for Safe Marker Handling nology. The TM-15 is precision engineered from magnesium alloy, aircraft- IMPORTANT: Never carry your TM-15 uncased when not on a playing grade aluminum, and composite materials. We expect you to play hard and field. The non-playing public and law enforcement personnel may not be play frequently and the TM-15 was built with this in mind. able to distinguish between a paintball marker and firearm. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 188/Monday, September 28, 2020

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 188 / Monday, September 28, 2020 / Notices 60855 comment letters on the Proposed Rule Proposed Rule Change and to take that the Secretary of State has identified Change.4 action on the Proposed Rule Change. as a property that is owned or controlled On May 21, 2020, pursuant to Section Accordingly, pursuant to Section by the Cuban government, a prohibited 19(b)(2) of the Act,5 the Commission 19(b)(2)(B)(ii)(II) of the Act,12 the official of the Government of Cuba as designated a longer period within which Commission designates November 26, defined in § 515.337, a prohibited to approve, disapprove, or institute 2020, as the date by which the member of the Cuban Communist Party proceedings to determine whether to Commission should either approve or as defined in § 515.338, a close relative, approve or disapprove the Proposed disapprove the Proposed Rule Change as defined in § 515.339, of a prohibited Rule Change.6 On June 24, 2020, the SR–NSCC–2020–003. official of the Government of Cuba, or a Commission instituted proceedings For the Commission, by the Division of close relative of a prohibited member of pursuant to Section 19(b)(2)(B) of the Trading and Markets, pursuant to delegated the Cuban Communist Party when the 7 Act, to determine whether to approve authority.13 terms of the general or specific license or disapprove the Proposed Rule J. Matthew DeLesDernier, expressly exclude such a transaction. 8 Change. The Commission received Assistant Secretary. Such properties are identified on the additional comment letters on the State Department’s Cuba Prohibited [FR Doc. -

Dossier De Presse TOUT SAVOIR SUR EMPIRE

DOSSIER DE PRESSE TOUT SAVOIR SUR EMPIRE DÉCOUVRIR LES PREMIÈRES IMAGES DE LA SAISON 1 SUCCESS STORY : Série dramatique n°1 de la saison 2014/15 aux USA Série n°2 de la saison 2014/15 aux USA, derrière Big Bang Theory sur CBS Meilleur score pour une nouvelle série aux USA depuis Desperate Housewives et Grey’s Anatomy en 2004-2005 Plus forte progression durant une première saison (+65%) depuis Docteur House en 2004 Série la plus tweetée avec 627 369 live tweets par épisode (devant The Walking Dead) SYNOPSIS Lucious Lyon (Terrence Howard, nominé aux lorsque son ex-femme, Cookie (Taraji P. Henson, Oscars et aux Golden Globes pour Hustle & nominée aux Oscars et aux Emmy Awards, Flow) est le roi du hip-hop. Ancien petit voyou, L’étrange histoire de Benjamin Button, Person son talent lui a permis de devenir un artiste of Interest), revient sept ans plus tôt que prévu, talentueux mais surtout le président d’Empire après presque 20 ans de détention. Audacieuse Entertainment. Pendant des années, son et sans scrupule, Cookie considère qu’elle s’est règne a été sans partage. Mais tout bascule sacrifiée pour que Lucious puisse démarrer sa lorsqu’il apprend qu’il est atteint d’une maladie carrière puis bâtir un empire, en vendant de la dégénérative. Il est désormais contraint de drogue. Trafic pour lequel elle a été envoyée transmettre à ses trois fils les clefs de son en prison. empire, sans faire éclater la cellule familiale déjà fragile. Pour le moment, Lucious reste à la tête d’Empire Entertainment.