“Cuba's Revolutionary Armed Forces: How Revolutionary Have They

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New York Transit Workers Vote to Authorize Strike

ICELAND KR200 · NEW ZEALAND $3.00 · SWEDEN KR15 · UK £1.00 · U.S. $1.50 I.ESSDNS FROM REVDUJTIDNARY HISTORY 'Marianas in Combat': women and the Cuban Revolution THE -PAGES6-7 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF WORKING PEOPLE VOL. 66/NO. 48 DECEMBER 23, 2002 New York transit workers Washington releases vote to authorize strike plans for BY STU SINGER • • AND OLGA RODRIGUEZ NEW YORK-More than 10,000 work reservtsts tn ers on the New York City bus and subway system, members of the Transport Workers Union (TWU), met here in two separate shift waronlraq meetings and voted overwhelmingly to au- BY BRIAN WILLIAMS Putting in place the front-line and backup forces for an invasion of Iraq, Washington Support transit has released plans for an increased mobili zation ofNational Guard and Reserve troops. workers' fight Up to 10,000 such forces will be imme diately activated for "security duty" in the SEEPAGE 15 1'0!>('['"1"·. ~ United States and abroad. With an order to . L·\\1\IS invade, that number would increase to more thorize a strike after their contract expires than a quarter of a million troops stationed December 15. at airports, train stations, power plants, fac The December 7 meeting was marked by tories, and military bases. the determination of the transit workers to The number is in addition to the more than defend their working conditions, benefits, ealth Benef1t~ 2\P CLASS 50,000 reservists already mobilized through and wages in face of the offensive by the out the United States. The plans include wealthy rulers against the working people coastline patrols by Navy and Coast Guard Continued on Page 5 Participants in October------· 30 transit workers' rally state their demands in contract fight Reserve forces. -

Overview Print Page Close Window

World Directory of Minorities Americas MRG Directory –> Cuba –> Cuba Overview Print Page Close Window Cuba Overview Environment Peoples History Governance Current state of minorities and indigenous peoples Environment Cuba is the largest island in the Caribbean. It is located 150 kilometres south of the tip of the US state of Florida and east of the Yucatán Peninsula. On the east, Cuba is separated by the Windward Passage from Hispaniola, the island shared by Haiti and Dominican Republic. The total land area is 114,524 sq km, which includes the Isla de la Juventud (formerly called Isle of Pines) and other small adjacent islands. Peoples Main languages: Spanish Main religions: Christianity (Roman Catholic, Protestant), syncretic African religions The majority of the population of Cuba is 51% mulatto (mixed white and black), 37% white, 11% black and 1% Chinese (CIA, 2001). However, according to the Official 2002 Cuba Census, 65% of the population is white, 10% black and 25% mulatto. Although there are no distinct indigenous communities still in existence, some mixed but recognizably indigenous Ciboney-Taino-Arawak-descended populations are still considered to have survived in parts of rural Cuba. Furthermore the indigenous element is still in evidence, interwoven as part of the overall population's cultural and genetic heritage. There is no expatriate immigrant population. More than 75 per cent of the population is classified as urban. The revolutionary government, installed in 1959, has generally destroyed the rigid social stratification inherited from Spanish colonial rule. During Spanish colonial rule (and later under US influence) Cuba was a major sugar-producing territory. -

Cuba Travelogue 2012

Havana, Cuba Dr. John Linantud Malecón Mirror University of Houston Downtown Republic of Cuba Political Travelogue 17-27 June 2012 The Social Science Lectures Dr. Claude Rubinson Updated 12 September 2012 UHD Faculty Development Grant Translations by Dr. Jose Alvarez, UHD Ports of Havana Port of Mariel and Matanzas Population 313 million Ethnic Cuban 1.6 million (US Statistical Abstract 2012) Miami - Havana 1 Hour Population 11 million Negative 5% annual immigration rate 1960- 2005 (Human Development Report 2009) What Normal Cuba-US Relations Would Look Like Varadero, Cuba Fisherman Being Cuban is like always being up to your neck in water -Reverend Raul Suarez, Martin Luther King Center and Member of Parliament, Marianao, Havana, Cuba 18 June 2012 Soplillar, Cuba (north of Hotel Playa Giron) Community Hall Questions So Far? José Martí (1853-95) Havana-Plaza De La Revolución + Assorted Locations Che Guevara (1928-67) Havana-Plaza De La Revolución + Assorted Locations Derek Chandler International Airport Exit Doctor Camilo Cienfuegos (1932-59) Havana-Plaza De La Revolución + Assorted Locations Havana Museo de la Revolución Batista Reagan Bush I Bush II JFK? Havana Museo de la Revolución + Assorted Locations The Cuban Five Havana Avenue 31 North-Eastbound M26=Moncada Barracks Attack 26 July 1953/CDR=Committees for Defense of the Revolution Armed Forces per 1,000 People Source: World Bank (http://databank.worldbank.org/data/Home.aspx) 24 May 12 Questions So Far? pt. 2 Marianao, Havana, Grade School Fidel Raul Che Fidel Che Che 2+4=6 Jerry Marianao, Havana Neighborhood Health Clinic Fidel Raul Fidel Waiting Room Administrative Area Chandler Over Entrance Front Entrance Marianao, Havana, Ration Store Food Ration Book Life Expectancy Source: World Bank (http://databank.worldbank.org/data/Home.aspx) 24 May 12. -

Cuba: Carnaval Cuban Style

INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS 535 Fifth Avenue New York, N.Y. 10017 FJM-30: Cuba Havana, Cuba Carnaval Cub an Style July 20, 1971 2. FJM-30 In December 1970, while speaking before an assembly of light industry workers, Fidel told the Cubans that for the second year in a row they would have to cancel Christmas and New Year celebrations. Instead, there would be Carnaval in July. "We'd love to celebrate New Year's Eve, January i and January 2. Naturally. Who doesn't? But can we afford such luxuries now, the way things stand? There is a reality. Do we have traditions? Yes. Very Christian traditions? Yes. Very beautiful traditions? Very poetic traditions? Yes, of course But gentlemen, we don't live in Sweden or Belgium or Holland. We live in the tropics. Our traditions were brought in from Europe--eminently respectable traditions and all that, but still imported. Then comes the reality about this country" ours is a sugar- growing country...and sugar cane is harvested in cool, dry weather. What are the best months for working from the standpoint of climate? From November through May. Those who established the tradition listen if they had set Christmas Eve for July 24, we'd .be more than happy. But they stuck everybody in the world with the same tradition. In this case are we under any obligation? Are the conditions in capitalism the same as ours? Do we have to bow to certain traditions? So I ask myself" even wen we have the machines, can we interrupt our work in the middle of December? [exclamations of "No!"] And one day even the Epiphan festivities will be held in July because actually the day the children of this countr were reborn was the day the Revolution triumphed." So this summer there is carnaval in July" Cuban Christmas, New Years and Mardi Gras all in one. -

U.S. Policy Toward the Caribbean in the 1980S

U.S. Policy Toward the Caribbean in the 1980s -- Paper presented by Roland I. Perusse, Director, Inter American InstitUte of Puerto Rico, at the Ninth Annual Meeting of the Caribbean Studies Association, St.Kitts—Nevis, May 30 to June 2, 1984 The change in U.S. Presidents on January 20, 1981, from Jimmy Carter, the humanitarian, to Ronald Reagan, the realist, brought about sharp changes in U.S. foreign policy around the world, but especially in the Caribbean region. The Jimmy Carter years were a search for accomondation with the Soviet Union and marxism. In the Caribbean, Carter sought to normalize relations with Cuba and to establish friendly relations with the aew Sandinista regime in Nicaragua. Carter pressed for respect of human rights around the world. In the Caribbean, he criticized. violations in Cuba, Haiti and the *Dominican Republic. He opened the gates of the United States to 100,000 refugees from Cuba and to several thousand % other "boat people' from Haiti. Realist Ronald Reagan views the world in terms of a confrontation between the "evil empire" of communism and western concepts of democracy. With respect to the Caribbean, he recognizes the need to attack basic social, economic and political problems, but feels that the Soviet Union Cuba and Nicaragua are seeking to exploit the situation for the benefit of the world communist movement. Thus, marxist ideology and aggression are seen as posing the immediate threat to progress, stability and secur- ity in the region and to U.S. national interests in the Caribbean basin Western scholars, especially social scientists, have traditionally perceived Central America and the Caribbean to be two distinct regions. -

Millville, NJ

WfJ/iIlE/iS ".(;(/'11' 2se No. 500 ~X-523 20 April 1990 Wall Street Shudders After Tokyo Stock Market Crash Japan is supposed to be the ultimate, super-successful capitalist country. But in March and early April the Tokyo stock exchange experienced a meltdown wip ing out almost 30 percent of the market value of Japan, Inc. "There is a total loss of confidence, period," exclaimed one se curities dealer. "It's an ugly situation," echoed another. "There are no buyers at all. None." Nippon Telegraph and Tele-' phone-the largest corporation in the world-had its stock fall from a peak of $21,000 per share a few years ago to less than $8,000. The Tokyo crash reverberated in finan cial capitals from Wall Street to Frank furt. The fear is that the Japanese will pull back and sell off their .assets to cover their losses at home. For most of the last decade, Japanese money has propped up the debt-ridden and decaying U.S. economy. Tokyo banks and securi ties outfits regularly purchase 30 to 40 percent of new U.S. Treasury bonds. Shigeo Kogure Without this Japanese money, T-bills World's biggest stock market loses almost 30 percent of value in a few months. would be selling at the same interest rates as junk bonds. But now the great Thus at the very moment that the Economic conflicts between American that smoothly as the economic "shock "leveraged buyout" of East Europe, chan rulers of world imperialism are proclaim and Japanese capitalism continue to treatment" designed for Poland meets neled through the banking houses of ing "the death of Communism" as "the escalate toward full-scale trade war. -

U.S. Citizens Killed Or Disappeared by Cuba's

U.S. CITIZENS KILLED OR DISAPPEARED Francis Brown, age 68. Assassinated BY CUBA’S COMMUNIST REGIME extrajudicially April 27, 1978, Guantánamo hospital. Former World War II veteran who, when 48 documented cases 1959 to date the Castro regime rose to power, worked as a diver at the U.S. Guantanamo Naval Base and had a Update of September 2018 Cuban wife and daughter. A co-worker alerted him that the Cuban regime had ordered him killed to Work in progress blame the U.S. government and provoke a See case details at database.CubaArchive.org confrontation. He resigned from his job at the base to avoid being used as pawn, but remained in Cuba trying to get his family out. Falsely accused of kidnapping his own daughter and imprisoned after his release, he was under constant surveillance and control of the secret police. On the eve of a visit I. 22 U.S. citizens executed, by a friendly U.S. African-American delegation, he developed high blood assassinated, or disappeared pressure and went to the hospital emergency room. Under control of State Executions by firing squad: 8 Security agents, he was given an injection that almost immediately caused Extrajudicial Assassinations: 11 him to foam at the mouth and die. His daughter believes he was killed to Forced Disappearance: 1 avoid a public relations’ problem. Politically induced suicide: 2 In alphabetical order Frederic Richard Carter. Assassinated extrajudicially August 11, 1982, State Security headquarters in Havana. Resident of Armando Alejandre Jr., age 45. Assassinated Havana, Cuba, reportedly killed under arrest. extrajudicially February 24, 1996, inter- national airspace over the Straits of Florida. -

Restless.Pdf

RESTLESS THE STORY OF EL ‘CHE’ GUEVARA by ALEX COX & TOD DAVIES first draft 19 jan 1993 © Davies & Cox 1993 2 VALLEGRANDE PROVINCE, BOLIVIA EXT EARLY MORNING 30 JULY 1967 In a deep canyon beside a fast-flowing river, about TWENTY MEN are camped. Bearded, skinny, strained. Most are asleep in attitudes of exhaustion. One, awake, stares in despair at the state of his boots. Pack animals are tethered nearby. MORO, Cuban, thickly bearded, clad in the ubiquitous fatigues, prepares coffee over a smoking fire. "CHE" GUEVARA, Revolutionary Commandant and leader of this expedition, hunches wheezing over his journal - a cherry- coloured, plastic-covered agenda. Unable to sleep, CHE waits for the coffee to relieve his ASTHMA. CHE is bearded, 39 years old. A LIGHT flickers on the far side of the ravine. MORO Shit. A light -- ANGLE ON RAUL A Bolivian, picking up his M-1 rifle. RAUL Who goes there? VOICE Trinidad Detachment -- GUNFIRE BREAKS OUT. RAUL is firing across the river at the light. Incoming bullets whine through the camp. EVERYONE is awake and in a panic. ANGLE ON POMBO CHE's deputy, a tall Black Cuban, helping the weakened CHE aboard a horse. CHE's asthma worsens as the bullets fly. CHE Chino! The supplies! 3 ANGLE ON CHINO Chinese-Peruvian, round-faced and bespectacled, rounding up the frightened mounts. OTHER MEN load the horses with supplies - lashing them insecurely in their haste. It's getting light. SOLDIERS of the Bolivian Army can be seen across the ravine, firing through the trees. POMBO leads CHE's horse away from the gunfire. -

Oriente Province Begin

• Inter - American News ¦p a p-M Member Inter American wHk mb I Press Association for English - • Speaking people For Liberty, Culture and Daily Hemispheric Solidarity he for a better understanding between the T Americas 4th YEAR MIAMI SPRINGS, FLA., SUNDAY, JUNE 2, 1957 NUMBER 271 G. A. SAN ROMAN C. W. SMITH S. SMITH President Vice President Vice President Nicaragua FRANCISCO AGUIRRE HORACIO AGUIRRE and Vice President and Publisher Vice President Editor and Manager Sen. Smathers Proposes Antonio Ruiz Fred M. Shaver Eliseo Riera-G6mez Large Scale Operations Managing Editor Business Manager Advt. Si Clre. Mgr. Honduras Agree Published daily except Monday Entered as second class matter at the Amendment to Provide a Post Office of Miami Springs. Fla., on February 8. 1956. Against Cuban Rebels in EDITORIAL Fund for Latin America to Avoid Use U.S. CONSULAR SERVICE IN LATIN AMERICA WASHINGTON The Senator from Florida, George Smathers of Violence The existing restrictions and requirements regarding (Democrat), this week proposed an Oriente Province Begin visas for residents and tourists wishing to travel to the amendment to the Mutual Secur- GUATEMALA, June HUP) United States have complicated, no doubt, the functions of ity Authorization Bill which would Honduras and Nicaragua agreed to the consulates of this country in the whole world. provide for a $25 million economic a solution of their territorial con- BATISTA DENIES Cuban Leader Ready to Participate development fund for Latin Ame- flict without the use of violence, For Latin America the -

Redalyc.SUGAR, EMPIRE, and REVOLUTION in EASTERN CUBA

Caribbean Studies ISSN: 0008-6533 [email protected] Instituto de Estudios del Caribe Puerto Rico Casey, Matthew SUGAR, EMPIRE, AND REVOLUTION IN EASTERN CUBA: THE GUANTÁNAMO SUGAR COMPANY RECORDS IN THE CUBAN HERITAGE COLLECTION Caribbean Studies, vol. 42, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2014, pp. 219-233 Instituto de Estudios del Caribe San Juan, Puerto Rico Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=39240402008 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative SUGAR, EMPIRE, AND REVOLUTION IN EASTERN CUBA... 219 SUgAR, EMPIRE, AND REVOLUTION IN EASTERN CUBA: ThE gUANTáNAMO SUgAR COMPANy RECORDS IN ThE CUBAN hERITAgE COLLECTION Matthew Casey ABSTRACT The Guantánamo Sugar Company Records in the Cuban Heritage Col- lection at the University of Miami represent some of the only accessible plantation documents for the province of Guantánamo in republican Cuba. Few scholars have researched in the collection and there have not been any publications to draw from it. Such a rich collection allows scholars to tie the province’s local political, economic, and social dynamics with larger national, regional, and global processes. This is consistent with ongoing scholarly efforts to understand local and global interactions and to pay more attention to regional differences within Cuba. This research note uses the records to explore local issues of land, labor, and politics in republican-era Guantánamo in the context of larger national and international processes. -

Studyteam Cuba, Havana

AGENT MANUAL 2018 HAVANA TRINIDAD AND SANTIAGO DE CUBA Book at worldwide lowest price at: https://www.languagecourse.net/zh/school-studyteam-cuba-havana +1 646 503 18 10 +44 330 124 03 17 +34 93 220 38 75 +33 1-78416974 +41 225 180 700 +49 221 162 56897 +43 720116182 +31 858880253 +7 4995000466 +46 844 68 36 76 +47 219 30 570 +45 898 83 996 +39 02-94751194 +48 223 988 072 +81 345 895 399 +55 213 958 08 76 +86 19816218990 StudyTeam Cuba 2018 Havana, Trinidad and Santiago de Cuba Learn and Enjoy the Cuban way! ABOUT US As of 1997 StudyTeam Cuba offers Spanish courses in Santiago de Cuba and from 2000 onwards we initialized the same program in Havana. Later in 2002 the same initiative was founded in Trinidad. As a way to make our contribution to Cuban culture stronger, StudyTeam has a joint venture with “Paradiso”, the Agency for Cultural Tourism of the Large Caribbean Island. Our Spanish language program includes mini group intensive classes and individual lessons. All teachers are native, highly educated speakers and have been well trained in language teaching to foreigners. For accommodation, we have carefully selected host families in the best neighbourhoods for an enjoyable stay and a real experience of local lifestyle. Students can combine a Spanish language course with dance or music lessons for a complete immersion in the artistic Cuban culture. Activities and excursions are an important part of the program as well; every week we organize social plans to help students visit the most attractive places in Cuba and enjoy the local events. -

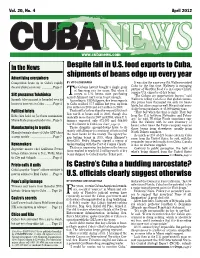

Is Castro's Cuba a Budding Narcostate?

Vol. 20, No. 4 April 2012 In the News Despite fall in U.S. food exports to Cuba, Advertising everywhere shipments of beans edge up every year Competition heats up in Cuba’s rapidly BY VITO ECHEVARRÍA It was also the same year Pat Wallesen visited decentralizing economy ................Page 3 he Cubans haven’t bought a single grain Cuba for the first time. Wallesen is managing of American rice for years. But when it partner of WestStar Food Co. in Corpus Christi, Tcomes to U.S. beans, state purchasing a major U.S. exporter of dry beans. SEC pressures Telefónica agency Alimport can’t seem to get enough. “The Cubans are opportunistic buyers,” said Spanish telecom giant is hounded over its According to USDA figures, dry bean exports Wallesen, telling CubaNews that global commo- business interests in Cuba ............Page 4 to Cuba reached $7.7 million last year, up from dity prices have fluctuated not only for beans lately, but other crops as well. He put total annu- $5.6 million in 2010 and $4.3 million in 2009. al dry bean purchases at 45,000 metric tons. Political briefs That’s still a lot less than the record $10.9 mil- “They buy when the time is right. They buy lion worth of beans sold in 2006, though dra- from the U.S. between November and Febru- Rubio lifts hold on Jacobson nomination; matically more than in 2007 and 2008, when U.S. Miami-Dade proposal under fire ...Page 5 ary,” he said. WestStar Foods sometimes sup- farmers exported only $73,000 and $68,000 plies the Cubans with its own inventory of worth of beans to Cuba (see chart, page 3).