The Web of Indian Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religion and Identity

The Journal of the International Society for Frontier Missiology Int’l Journal of Frontier Missiology Religion and Identity 159 From the Editor’s Desk Brad Gill Profiling Religion, Blurring Identity 161 Articles 161 Caste, Christianity, and Cross-Cultural Evangelism Revisted N. J. Gnaniah Is caste or caste-ism the real problem? 169 The Virgin of Guadalupe: A Study of Socio-Religious Identity Allen Yeh and Gabriela Olaguibel Can we suspend the verdict of syncretism long enough to learn about identity? 179 Mission at the Intersection of Religion and Empire Martin Accad Is our way of “being Christian” among Muslims a colonial hangover? 191 Going Public with Faith in a Muslim Context: Lessons from Esther Jeff Nelson Do we need Esther when we’ve got Paul? 196 Book Reviews Wrestling with Religion: Exposing a Taken-for-Granted Assumption in Mission 196 The Birth of Orientalism 197 A New Science: The Discovery of Religion in the Age of Reason 198 Orientalists, Islamists and the Global Public Sphere: A Genealogy of the Modern Essentialist Image of Islam 200 Unifying Hinduism: Philosophy and Identity in Indian Intellectual History 201 Religion and the Making of Modern East Asia l Secularism and Religion-Making 202 God is Not One: The Eight Rival Religions the Run the World 204 A Theological Analysis of the Insider Movement Paradigm from Four Perspectives: Theology of Religions, Revelation, Soteriology and Ecclesiology 210 In Others’ Words 210 Translating “Son of God” “Insider Movement” in a Surprising Place? Religion and Identity Mobile Technology and Ministry 2October–December8: 20114 WILLIAM CAREY LIBRARY NEW RELEASE DONALD MMcGAVRANcGAVRAN HIS EARLY LIFE AND MINISTRY An Apostolic Vision for Reaching the Nations Donald McGavran a biography His Early Life and Ministry An Apostolic Vision for Reaching the Nations Th is biography is more than one man’s interpretation of another person’s life—it has numerous traits of an autobiography. -

Handbook of Religious Beliefs and Practices

STATE OF WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES 1987 FIRST REVISION 1995 SECOND REVISION 2004 THIRD REVISION 2011 FOURTH REVISION 2012 FIFTH REVISION 2013 HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES INTRODUCTION The Department of Corrections acknowledges the inherent and constitutionally protected rights of incarcerated offenders to believe, express and exercise the religion of their choice. It is our intention that religious programs will promote positive values and moral practices to foster healthy relationships, especially within the families of those under our jurisdiction and within the communities to which they are returning. As a Department, we commit to providing religious as well as cultural opportunities for offenders within available resources, while maintaining facility security, safety, health and orderly operations. The Department will not endorse any religious faith or cultural group, but we will ensure that religious programming is consistent with the provisions of federal and state statutes, and will work hard with the Religious, Cultural and Faith Communities to ensure that the needs of the incarcerated community are fairly met. This desk manual has been prepared for use by chaplains, administrators and other staff of the Washington State Department of Corrections. It is not meant to be an exhaustive study of all religions. It does provide a brief background of most religions having participants housed in Washington prisons. This manual is intended to provide general guidelines, and define practice and procedure for Washington State Department of Corrections institutions. It is intended to be used in conjunction with Department policy. While it does not confer theological expertise, it will, provide correctional workers with the information necessary to respond too many of the religious concerns commonly encountered. -

The Religious Lifeworlds of Canada's Goan and Anglo-Indian Communities

Brown Baby Jesus: The Religious Lifeworlds of Canada’s Goan and Anglo-Indian Communities Kathryn Carrière Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the PhD degree in Religion and Classics Religion and Classics Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Kathryn Carrière, Ottawa, Canada, 2011 I dedicate this thesis to my husband Reg and our son Gabriel who, of all souls on this Earth, are most dear to me. And, thank you to my Mum and Dad, for teaching me that faith and love come first and foremost. Abstract Employing the concepts of lifeworld (Lebenswelt) and system as primarily discussed by Edmund Husserl and Jürgen Habermas, this dissertation argues that the lifeworlds of Anglo- Indian and Goan Catholics in the Greater Toronto Area have permitted members of these communities to relatively easily understand, interact with and manoeuvre through Canada’s democratic, individualistic and market-driven system. Suggesting that the Catholic faith serves as a multi-dimensional primary lens for Canadian Goan and Anglo-Indians, this sociological ethnography explores how religion has and continues affect their identity as diasporic post- colonial communities. Modifying key elements of traditional Indian culture to reflect their Catholic beliefs, these migrants consider their faith to be the very backdrop upon which their life experiences render meaningful. Through systematic qualitative case studies, I uncover how these individuals have successfully maintained a sense of security and ethnic pride amidst the myriad cultures and religions found in Canada’s multicultural society. Oscillating between the fuzzy boundaries of the Indian traditional and North American liberal worlds, Anglo-Indians and Goans attribute their achievements to their open-minded Westernized upbringing, their traditional Indian roots and their Catholic-centred principles effectively making them, in their opinions, admirable models of accommodation to Canada’s system. -

Exigency of Intellectuality and Pragmatic Reasoning Against Credulity

© 2019 JETIR May 2019, Volume 6, Issue 5 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) EXIGENCY OF INTELLECTUALITY AND PRAGMATIC REASONING AGAINST CREDULITY. (COUNTERFEIT PROPHECY, SUPERSTITION, ASTROLOGY AND VIGILANT GLOBE) Bhaskar Bhuyan India, State- Assam, Dist- Lakhimpur, Pin-787023 ABSTRACT Along with advancement and technology, still some parts of the globe are greatly affected by fake beliefs. Future is unpredictable and black magic is superstition. Necessity lies in working for future rather than knowing it. Lack of intelligence is detrimental for a society. Astrology is not a science, Astronomy is science. Astrologers predict by the influence of planets and they create a psychological game. In other words they establish a perfect marketing and affect the life of an individual in every possible way. Superstition is still ruling and it is degrading the development. Key words: Superstition, Astrology and black magic. 1.0 INTRODUCTION: The globe is still not equally equipped with development, advancement and intellectuality. Some 5000 years ago, superstition started to merge out from the ancient Europe and got spread to entire Globe. Countries like China, Greece, India, United Kingdom, Japan, Thailand, Ireland, Italy, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal etc are influenced by black magic, superstition, astrology and fake Beliefs. Almost 98 countries out of 195 are affected by credulity. Orating the scenario of ancient time and comparing it with the present arena, it is still not degraded. The roots of this belief starts from the village and gets spread socially due to migration and social media across the entire district, state and country. 2.0 SUPERSITION IN VARIOUS COUNTRIES: 2.1 JAPAN: 1. -

Chapter Ii a Brief History of the Church in Kerala

CHAPTER II A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE CHURCH IN KERALA Traditionally, Kerala extended from Gokarnam to Cape Comorin, but in historical times its area was confined to the Malayalam speaking territories on the coasts. The country slopes from East to West, with uplands and hills in the East, and plains, lowlands and fields on the western section. The coastal region is almost at the sea level, while the western ghats in the East form an almost unbroken range of mountains, some of which are as high as 10,000 feet. These mountains separate or in some way isolate Kerala from the rest of India, It might, therefore, appear that the Malayalis from the beginning have lived a life of their own. But Kerala's connections across the sea with the countries bordering on the Arabian sea was continuous and of particular significance, which have affected its society and culture. The Church, in fact, traces its origin to these connections, 2 Non-Christian Communities _ Kerala is an instance of the communities of three major world religions - Hinduism, Islam and Christianity - living within one territory. The Hindu community of Kerala experienced the most elaborate system of caste found in India, With 365 divisions and subdivisions,-^ and conceptions of purity and pollution which extended beyond untouchability 42 43 to unapproachability, Kerala was described by Vivekananda as a mad house of caste, *" Yet, the system was unusual in its structure. For, of the four basic varnas, Kshatriyaa were rare and Vaisyas almost non-existent, Nairs took the place of Kshatriyas, though they were regarded as Sudras by the Namboodiri Brahmins. -

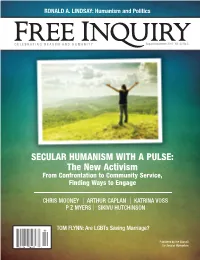

SECULAR HUMANISM with a PULSE: the New Activism from Confrontation to Community Service, Finding Ways to Engage

FI AS C1_Layout 1 6/28/12 10:45 AM Page 1 RONALD A. LINDSAY: Humanism and Politics CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY August/September 2012 Vol. 32 No.5 SECULAR HUMANISM WITH A PULSE: The New Activism From Confrontation to Community Service, Finding Ways to Engage CHRIS MOONEY | ARTHUR CAPLAN | KATRINA VOSS P Z MYERS | SIKIVU HUTCHINSON 09 TOM FLYNN: Are LGBTs Saving Marriage? Published by the Council for Secular Humanism 7725274 74957 FI Aug Sept CUT_FI 6/27/12 4:54 PM Page 3 August/September 2012 Vol. 32 No. 5 CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY 20 Secular Humanism With A Pulse: 30 Grief Beyond Belief The New Activists Rebecca Hensler Introduction Lauren Becker 32 Humanists Care about Humans! Bob Stevenson 22 Sparking a Fire in the Humanist Heart James Croft 34 Not Enough Marthas Reba Boyd Wooden 24 Secular Service in Michigan Mindy Miner 35 The Making of an Angry Atheist Advocate EllenBeth Wachs 25 Campus Service Work Franklin Kramer and Derek Miller 37 Taking Care of Our Own Hemant Mehta 27 Diversity and Secular Activism Alix Jules 39 A Tale of Two Tomes Michael B. Paulkovich 29 Live Well and Help Others Live Well Bill Cooke EDITORIAL 15 Who Cares What Happens 56 The Atheist’s Guide to Reality: 4 Humanism and Politics to Dropouts? Enjoying Life without Illusions Ronald A. Lindsay Nat Hentoff by Alex Rosenberg Reviewed by Jean Kazez LEADING QUESTIONS 16 CFI Gives Women a Voice with 7 The Rise of Islamic Creationism, Part 1 ‘Women in Secularism’ Conference 58 What Jesus Didn’t Say A Conversation with Johan Braeckman Julia Lavarnway by Gerd Lüdemann Reviewed by Robert M. -

5. the Other Side of Freedom of Religion in India

2015 (2) Elen. L R 5. THE OTHER SIDE OF FREEDOM OF RELIGION IN INDIA Vipin Das R V1 Introduction Freedom of religion is considered as the precious possession of every individual from the inception of mankind (Harold E., 2002).2 Every modern nation in the world, in their Constitutions, clearly establishes the right to freedom of religion, belief, faith, thought, and expression of all these freedoms to all its citizens. Many a time, these expressions and practices attributed to religions, faith and beliefs become blind. Citizens or the people following such blind belief and faith on religion and practising so-called religious activities infringes forcefully the human right of others to live with dignity and status. The recent news and reports from print and television media reveals the truth that exploitations in the name of black magic are on the rise in Kerala as well as in India.3 Superstition- General meaning. The term „Superstition‟ is a complex term having no clear definition. In practical sense superstition is an elastic term which could be at once narrowly defined to exclude individual practice and also can be stretched to include a wide spectrum of beliefs, rites, 1 Research Scholar, NUALS. Email: [email protected] 2 See generally Lurier, Harold E. (2002), A History of the Religions of the World, Indiana: Xlibris Corporation Publishers. 3 See for examples, The search list generated in NDTV website for the key word “Black Magic”, a minimum of 40 recent reports could be identified. URL: http://www.ndtv.com/topic/black-magic (Last -

Volume 11 Number 4 October-December 2019

I Volume 11 Number 4 October-December 2019 International Journal of Nursing Education Editor-in-Chief Amarjeet Kaur Sandhu Principal & Professor, Ambika College of Nursing, Mohali, Punjab E-mail: [email protected] INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD NATIONAL EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD 1. Dr. Arnel Banaga Salgado (Asst. Professor) 4. Fatima D’Silva (Principal) Psychology and Psychiatric Nursing, Center for Educational Nitte Usha Institute of nursing sciences, Karnataka Development and Research (CEDAR) member, Coordinator, 5. G.Malarvizhi Ravichandran RAKCON Student Affairs Committee,RAK Medical and PSG College of Nursing, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu Health Sciences University, Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates 6. S. Baby (Professor) (PSG College of Nursing, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, Ministry of Health, New Delhi 2. Elissa Ladd (Associate Professor) MGH Institute of Health Professions Boston, USA 7. Dr. Elsa Sanatombi Devi (Professor and Head) Meidcal Surgical Nursing, Manipal Collge of nursing, Manipal 3. Roymons H. Simamora (Vice Dean Academic) Jember University Nursing School, PSIK Universitas Jember, 8. Dr. Baljit Kaur (Prof. and Principal) Jalan Kalimantan No 37. Jember, Jawa Timur, Indonesia Kular College of Nursing, Ludhiana, Punjab 4. Saleema Allana (Assistant Professor) 9. Mrs. Josephine Jacquline Mary.N.I (Professor Cum AKUSONAM, The Aga Khan University, School of Nursing Principal) Si-Met College of Nursing, Udma, Kerala and Midwifery, Stadium Road, Karachi Pakistan 10. Dr. Sukhpal Kaur (Lecturer) National Institute of Nursing 5. Ms. Priyalatha (Senior lecturer) RAK Medical & Health Education, PGIMER, Chandigarh Sciences University, Ras Al Khaimah,UAE 11. Dr. L. Eilean Victoria (Professor) Dept. of Medical Surgical 6. Mrs. Olonisakin Bolatito Toyin (Senior Nurse Tutor) Nursing at Sri Ramachandra College School of Nursing, University College Hospital, Ibadan, Oyo of Nursing, Chennai, Tamil Nadu State, Nigeria 12. -

International Journal of English and Studies

SP Publications International Journal Of English and Studies (IJOES) An International Peer-Reviewed Journal ; Volume-2, Issue-11, 2020 www.ijoes.in ISSN: 2581-8333; Impact Factor: 5.421(SJIF) RESEARCH ARTICLE SUPERSTITIOUSE BELIEF AND INDIAN SOCIETY ________________________________________________________________________ Asma Easmin (R esearch Scholar) Gauhati University ________________________________________________________________________ Abstract: Superstitions are common phenomenon in human society, especially in Asian cultures. Superstitious beliefs can have a negative impact on the social well being of people in society because they are highly associated with financial risk taking and gambling behavior. Superstitious beliefs have probably been present among us since the beginning of time and have been passed on through the centuries, culturally shared and transmitted from generation to generation. Keywords: Superstition, source of Superstition, Superstitious belief, reason, Indian Society. ISSN: 2581-8333 Copyright © 2020 SP Publications Page 135 SP Publications International Journal Of English and Studies (IJOES) An International Peer-Reviewed Journal ; Volume-2, Issue-11, 2020 www.ijoes.in ISSN: 2581-8333; Impact Factor: 5.421(SJIF) RESEARCH ARTICLE Methodology: The present study of superstitious belief and Indian society looks at the effects of different types of superstitious belief. This Paper is mainly presented in descriptive method through personal experience and other secondary data collecting sources. Introduction: A superstition is a belief or practice resulting from ignorance, fear of the unknown, trust in magic or chance or a false conception of causation or an irrational object attitude of mind towards the supernatural nature or God resulting from superstition. Often if arises from ignorance, a misunderstanding of science or causality, a belief in fate or magic, or fear of that which is unknown. -

Analysis of the Religious Practices of Hindus at Saint Joseph's Oratory

UNIVERSITÉ DE MONTRÉAL Analysis of the Religious Practices of Hindus at Saint Joseph’s Oratory Transmission of Christian Faith after the Second Vatican Council Par John Jomon Kalladanthiyil Faculté des arts et des sciences Institut d’études religieuses Thèse présentée en vue de l’obtention du grade de Ph. D. en Théologie pratique Mars 2017 © Jomon Kalladanthiyil, 2017 Résumé Dès le début du christianisme, la transmission de la foi chrétienne constitue la mission essentielle de l’Église. Dans un contexte pluri-religieux et multiculturel, le concile Vatican II a reconnu l’importance d’ouvrir la porte de l’Église à tous. Basile Moreau (1799 – 1873), le fondateur de la congrégation de Sainte-Croix, insistait sur le fait que les membres de sa communauté soient des éducateurs à la foi chrétienne et il a envoyé des missionnaires au Québec dès la fondation de sa communauté (1837). Pour ces derniers, parmi d’autres engagements pastoraux, l’Oratoire Saint-Joseph du Mont-Royal, fondé par Alfred Bessette, le frère André (1845 – 1937), est devenu l’endroit privilégié pour la transmission de la foi chrétienne, même après la Révolution tranquille des années 1960. L’Oratoire Saint-Joseph accueille des milliers d’immigrants du monde entier chaque année et parmi eux beaucoup d’hindous. Pour beaucoup d’entre eux, l’Oratoire devient un second foyer où ils passent du temps en prière et trouvent la paix. Certains d’entre eux ont l’expérience de la guérison et des miracles. Le partage de l’espace sacré avec les hindous est un phénomène nouveau à l’Oratoire. -

An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies

An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies Edited by Orlando O. Espín and James B. Nickoloff A Michael Glazier Book LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Michael Glazier Book published by Liturgical Press. Cover design by David Manahan, o.s.b. Cover symbol by Frank Kacmarcik, obl.s.b. © 2007 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, P.O. Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data An introductory dictionary of theology and religious studies / edited by Orlando O. Espín and James B. Nickoloff. p. cm. “A Michael Glazier book.” ISBN-13: 978-0-8146-5856-7 (alk. paper) 1. Religion—Dictionaries. 2. Religions—Dictionaries. I. Espín, Orlando O. II. Nickoloff, James B. BL31.I68 2007 200.3—dc22 2007030890 We dedicate this dictionary to Ricardo and Robert, for their constant support over many years. Contents List of Entries ix Introduction and Acknowledgments xxxi Entries 1 Contributors 1519 vii List of Entries AARON “AD LIMINA” VISITS ALBIGENSIANS ABBA ADONAI ALBRIGHT, WILLIAM FOXWELL ABBASIDS ADOPTIONISM -

IND34032 Country: India Date: 30 January 2009

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IND34032 Country: India Date: 30 January 2009 Title: India – Kerala – Mukkuva caste – Christians – Catholic Church Questions 1. Please provide background information on the Mukkuva caste community. 2. Please advise whether the RSS has targeted the Mukkuva caste community in Trivandrum? 3. Please advise whether the RSS has targeted Christians in Trivandrum? RESPONSE 1. Please provide background information on the Mukkuva caste community. Background information on Kerala‟s Christian Mukkuva caste (or jati) community was located within several anthropological and sociological studies. The Mukkuva are said to be principally Catholic, having been converted to the faith by St Francis Xavier in the 16th Century, and to be traditionally engaged in fishing. Two sources, a study produced by Kerala University‟s Loyola College of Social Sciences and a study produced by Robert Eric Frykenberg of the University of Wisconsin, relate that Kerala‟s Christian Mukkuva community have, historically, suffered economic and social marginalization as a consequence of their location within the polluted, or untouchable, strata of Kerala‟s caste relations. The website of the Kerala state government lists the Mukkuva communities on the “Other Eligible Community (O.E.C) List” as a community which is “Eligible for all Educational Assistance enjoyed by Scheduled Castes” (for an extensive anthropological overview of Kerala‟s Christian Mukkuva community, see: „Mukkuvan, Christian‟ in: Singh,