PRODUCTION NOTES “Flesh and Bone” Follows Claire, a Young Ballet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Sundance Film Festival Adds Four Films

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: December 14, 2016 Spencer Alcorn 310.360.1981 [email protected] BUT WAIT, THERE’S MORE! 2017 Sundance Film Festival Adds Four Films Two Documentary Premieres, Two From The Collection (L-R) Long Strange Trip, Credit: Andrew Kent; Reservoir Dogs, Courtesy of Sundance Institute; Bending The Arc, Courtesy of Sundance Institute; Desert Hearts, Courtesy of Sundance Institute. Park City, UT — Rounding out an already robust slate of new independent work, Sundance Institute adds two Documentary Premieres and two archive From The Collection films to the 2017 Sundance Film Festival. Screenings take place in Park City, Salt Lake City and at Sundance Mountain Resort January 19-29. Documentary Premieres Bending the Arc and Long Strange Trip join archive films Desert Hearts and Reservoir Dogs, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 1986 and 1992, respectively. The archive films are selections from the Sundance Institute Collection at UCLA, a joint venture between UCLA Film & Television Archive and Sundance Institute. The Collection, established in 1997, has grown to over 4,000 holdings representing nearly 2,300 titles, and is specifically devoted to the preservation of independent documentaries, narratives and short films supported by Sundance Institute, including Paris is Burning, El Mariachi, Winter’s Bone, Johnny Suede, Working Girls, Crumb, Groove, Better This World, The Oath and Paris, Texas. Titles are generously donated by individual filmmakers, distributors and studios. With these additions, the 2017 Festival will present 118 feature-length films, representing 32 countries and 37 first-time filmmakers, including 20 in competition. These films were selected from 13,782 submissions including 4,068 feature-length films and 8,985 short films. -

May 28, 2000 Hometownnewspapers.Net 75¢ Votume 35 Numeer 103 Westland

lomeTbwn COMMUNICATIONS NETWORK lUestlanu (Dbseruer * ' » W Your hometown newspaper serving Westland for 35 years Sunday, May 28, 2000 hometownnewspapers.net 75¢ Votume 35 Numeer 103 Westland. Michigan OC000 HomeTown Communications Network™ DEAR READERS: On Thursday, June 1, a new At Home section will debut in your Chi Id's death nets 13-25 years Weatlahd Observer. The new sec tion ii a broadsheet like the Assistant Wayne County Prosecutor viction. With 18 months served, his other section* in your Home- A local man has been imprisoned for the beat Jerry Dorsey IV said. sentence means that he could be Town Observer. This means ing death of a 3-year-oid child. The boy died A defense attorney had argued after released from prison before he is 40 more local news about garden from injuries supposedly inflicted because the the boy's death that Cobb didn't mean years old. •••••*•' ing, home decorating, home child urinated on a living room floor. to hurt the toddler when he hit him for Cobb was accused of beating Darius improvement and landscaping. urinating on a living room floor. Police while the boy's mother was at wofjt. Many features that our readers described Cobb as a 6-foot-1, 275-pound Somerset compared the toddler's look forward to each week such BYDABKELLCLEM ond-degree murder, man. injuries to those he would have suf as "The Appliance Doctor" and STAFF WROTE Cobb admitted killing toddler Darius dcIein00c.hoDiecomm.net fered by falling from a two- or three- "Marketplace" continue. Deshawn Conaway by beating him The force of the blow was enough to story building. -

Quentin Tarantino Retro

ISSUE 59 AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER FEBRUARY 1– APRIL 18, 2013 ISSUE 60 Reel Estate: The American Home on Film Loretta Young Centennial Environmental Film Festival in the Nation's Capital New African Films Festival Korean Film Festival DC Mr. & Mrs. Hitchcock Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Howard Hawks, Part 1 QUENTIN TARANTINO RETRO The Roots of Django AFI.com/Silver Contents Howard Hawks, Part 1 Howard Hawks, Part 1 ..............................2 February 1—April 18 Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances ...5 Howard Hawks was one of Hollywood’s most consistently entertaining directors, and one of Quentin Tarantino Retro .............................6 the most versatile, directing exemplary comedies, melodramas, war pictures, gangster films, The Roots of Django ...................................7 films noir, Westerns, sci-fi thrillers and musicals, with several being landmark films in their genre. Reel Estate: The American Home on Film .....8 Korean Film Festival DC ............................9 Hawks never won an Oscar—in fact, he was nominated only once, as Best Director for 1941’s SERGEANT YORK (both he and Orson Welles lost to John Ford that year)—but his Mr. and Mrs. Hitchcock ..........................10 critical stature grew over the 1960s and '70s, even as his career was winding down, and in 1975 the Academy awarded him an honorary Oscar, declaring Hawks “a giant of the Environmental Film Festival ....................11 American cinema whose pictures, taken as a whole, represent one of the most consistent, Loretta Young Centennial .......................12 vivid and varied bodies of work in world cinema.” Howard Hawks, Part 2 continues in April. Special Engagements ....................13, 14 Courtesy of Everett Collection Calendar ...............................................15 “I consider Howard Hawks to be the greatest American director. -

Nutcracker Salt Creek Ballet

Governors State University OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia Center for Performing Arts 12-14-1997 Nutcracker Salt Creek Ballet Follow this and additional works at: http://opus.govst.edu/cpa_memorabilia Recommended Citation Salt Creek Ballet, "Nutcracker" (1997, 1998, 2003, 2004, 2007, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2014, 2015). Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia. Book 113. http://opus.govst.edu/cpa_memorabilia/113 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Performing Arts at OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia by an authorized administrator of OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 9 E CENTER FOR ERFORMING ARTS Proudly Presents Salt Creek Ballet's The Nutcracker Featuring Principle Dancers of The American Ballet Theatre, New York December 14th, 1997 1 P.M. & 5 P.M Governors State University, University Park, IL I TheJtlinofs Philharmonic Orchestra presents a great way to Introduce your whole family to (he symphony, NEWTHJS SEASON,., Classics TH J ' *. **" *•* PICQACKER w*. t*. <<J nuaiy. Center for Performing Arts, Governors State University ' Gershwin, Bernstein and more... I Affordable... and close to home Free instrument demonstrations & soloist talk Stage commentary by Maestro Carmon DeLeone CELEBRATING For families... senior citizens... or anyone •wlwF J ^ifmmtmt %J who enjoys a Sunday afternoon at the symphony ORDER NOW... Call (708) 481-7774 Adult Tickets $26... $20... $16 MATTESON 18 and Under.... $13... $10.... $8 1997-98 Season Sponsor... indthnOfdciil Hotel e! the Illincli PMIhimonic Orchtttrt TREATSEATS TREATSEATS coupons for ticket discounts available at Target and Marshall Field's. -

AM ABT Featured Film Interviewees and Dances FINAL

Press Contact: Natasha Padilla, WNET, 212.560.8824, [email protected] Press Materials: http://pbs.org/pressroom or http://thirteen.org/pressroom Websites: http://pbs.org/americanmasters , http://facebook.com/americanmasters , @PBSAmerMasters , http://pbsamericanmasters.tumblr.com , http://youtube.com/AmericanMastersPBS , http://instagram.com/pbsamericanmasters , #ABTonPBS #AmericanMasters American Masters American Ballet Theatre: A History Premieres nationwide Friday, May 15, 2015 at 9 p.m. on PBS (check local listings) Film Interviewees and Featured Dances Film Interviewees (in alphabetical order) Alicia Alonso , dancer, ABT (1940-1960) Clive Barnes , dance critic, The New York Times (1965-1977); now deceased Mikhail Baryshnikov , principal dancer (1974-1978) & artistic director (1980-1989), ABT (archival) Lucia Chase , founding member & co-director (1945-1980), ABT; now deceased (archival) Misty Copeland , dancer, ABT (2001-present); third African-American female soloist and first in two decades at ABT Herman Cornejo , dancer, ABT (1999-present) Agnes de Mille , choreographer, charter member, ABT; now deceased (archival) Frederic Franklin , stager & guest artist, ABT (1997-2012); dancer; co-founder, Slavenska- Franklin Ballet; founding director, National Ballet of Washington, D.C.; now deceased Marcelo Gomes , dancer, ABT (1997-present) Jennifer Homans , author, Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet; founder and director, The Center for Ballet and the Arts at New York University Susan Jaffe , dancer (1980-2002) & ballet master (2010-2012), -

1 Fracking on Youtube

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Nottingham Trent Institutional Repository (IRep) Fracking on YouTube: Exploring risks, benefits and human values Rusi Jaspal De Montfort University, UK Andrew Turner University of Leicester, UK Brigitte Nerlich University of Nottingham, UK Fracking or the extraction of shale gas through hydraulic fracturing of rock has become a contested topic, especially in the United States, where it has been deployed on a large scale, and in Europe where it is still largely speculative. Research is beginning to investigate the environmental and economic costs and benefits as well as public perceptions of this new energy technology. However, so far the social and psychological impact of fracking on those involved in it, such as gas workers, or those living in the vicinity of fracking sites, has escaped the attention of the social science research community. In this article we begin to fill this gap through a small-scale thematic analysis of representations of fracking in 50 YouTube videos, where a trailer of a controversial film, Gasland (Fox, 2010), has had a marked impact. Results show that the videos discuss not only environmental and economic costs and benefits of fracking but also social and psychological impacts on individuals and communities. These videos reveal a human face of fracking that remains all too often hidden from view. Acknowledgements We would like to thank the ESRC for their financial support of project RES-360-25- 0068 and the University of Nottingham for additional financial support. Contact Dr Rusi Jaspal, School of Applied Social Sciences, Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, De Montfort University, Leicester LE1-9BH, United Kingdom. -

Artistic Directors Collection and from Other Retain Free General Admission but Make Ready-Made Villains

THE AUSTRALIAN, FRIDAY, JULY 29, 2011 www.theaustralian.com.au ARTS 15 Kelly’s gang exits In the company’s engine room in a blaze of glory CANBERRA’S National revenue,’’ Sayers says. ‘‘Free entry There’s much more to Museum of Australia will draw encourages greater visitation.’’ the artistic director’s the shutters this Sunday on the Unlike the leading museums role than just ordering most successful paid exhibition it in Sydney and Melbourne, has mounted, Not Just Ned; A admission to Canberra’s cultural the pink tutus True History of the Irish in institutions, including the Australia. National Portrait Gallery, VALERIE LAWSON More than 70,000 visitors National Gallery of Australia and have seen the display, which the War Memorial, has IN movie melodramas from The features hundreds of artefacts traditionally been free. Red Shoes to Centre Stage and from the museum’s own The National Museum will Black Swan the artistic directors collection and from other retain free general admission but make ready-made villains. The collections across the world. all significant temporary dancers are the heroes but the ‘‘We’re really pleased with the exhibitions will now be paid. bosses are the bullies, strutting way Not Just Ned has been One exception is an upcoming around their backstage domain, received,’’ says museum director China exhibition, a cultural abusing their fragile victims. Andrew Sayers. exchange show from which the Such cartoon characters had Anouk van Dijk Not Just Ned is not the most museum is contractually some real-life counterparts. popular show in the institution’s prevented from charging Sergei Diaghilev, for one, could O’Hare will be supported on the 10-year history. -

Fuel and Faith: a Spiritual Geography of Fossil Fuels in Western Canada

Fuel and Faith: a spiritual geography of fossil fuels in Western Canada by Darren Fleet M.J., University of British Columbia, 2011 B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2005 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Communication Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology © Darren Fleet 2021 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2021 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Declaration of Committee Name Darren Fleet Degree Doctor of Philosophy Title Fuel and Faith: a spiritual geography of fossil fuels in Western Canada Committee Chair: Siyuan Yin Assistant Professor, Communication Shane Gunster Supervisor Associate Professor, Communication Enda Brophy Committee Member Associate Professor, Communication Stephen Collis Committee Member Professor, English Am Johal Examiner Director, Vancity Office of Community Engagement Imre Szeman External Examiner Professor, Communication Arts University of Waterloo ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract With the acceleration of climate change, Canada's commitment to action on carbon emissions faces several vital contradictions. These tensions have economic, social, and communicative dimensions. This research seeks to investigate some of these manifestations by looking at how energy is understood and articulated through the lens of faith. Unique to the Canadian cultural/petrol landscape is that the physical geography of extraction -

This Document Is for Planning Purposes, We Kindly Ask That You Do Not Link out to This Document in Your Coverage**

**This document is for planning purposes, we kindly ask that you do not link out to this document in your coverage** Netflix 2021 Film Preview | Official Trailer YouTube Link (in order of appearance) Red Notice (Ryan Reynolds, Gal Gadot, Dwayne Johnson) The Harder They Fall (Regina King, Jonathan Majors) Thunder Force (Octavia Spencer, Melissa McCarthy) Bruised (Halle Berry) tick, tick… BOOM! (Lin-Manuel Miranda) The Kissing Booth 3 (Joey King) To All The Boys: Always And Forever (Lana Condor, Noah Centineo) The Woman in the Window (Amy Adams) Escape from Spiderhead (Chris Hemsworth) YES DAY(Jennifer Garner) Sweet Girl (Jason Momoa) Army of the Dead (Dave Bautista) Outside the Wire Bad Trip O2 The Last Mercenary Kate Fear Street Night Teeth Malcolm and Marie Monster Moxie The White Tiger Double Dad Back to the Outback Beauty Red Notice Don't Look Up 2 2021 NETFLIX FILMS (A-Z) 8 Rue de l'Humanité* O2* A Boy Called Christmas Outside the Wire (January 15) A Castle for Christmas Penguin Bloom (January 27)** Afterlife of the Party Pieces of a Woman (January 7) Army of the Dead Red Notice Awake Rise of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles A Week Away Robin Robin A Winter’s Tale from Shaun the Sheep** Skater Girl Back to the Outback Stowaway** Bad Trip Sweet Girl Beauty The Dig (January 29) Blonde The Guilty Blood Red Sky* The Hand of God* Bombay Rose The Harder They Fall Beckett The Kissing Booth 3 Bruised The Last Letter from Your Lover** Concrete Cowboy The Last Mercenary* Don't Look Up The Loud House Movie Double Dad* The Power of the -

Basic Black Or Whatever It Was That Other Boys Did

Basic Black or whatever it was that other boys did. It was at this time that I started wearing a dance belt, but the kind for boys without the thong. Instead they are thick nylon and elastic tighty- whities, Spanx for your junk. Ian Spencer Bell In tights I was aware of my body, entirely. I could feel my saggy middle over the Capezio I was seven or eight when I first put on a pair waistband, the two seams that made lines up of tights. It would have been about 1985. I re- the backs of my legs, the seam that went into member the tights well: black Capezio footed, my behind, and the gather of nylon around my seamed nylon tights, the kind Baryshnikov privates, now no longer so private. It was like supposedly wore. Men’s tights sizes have al- being in a pageant, in the spotlight. I imag- ways been confusing to me. When I was at my ined myself on a float or in a parade or sign- thinnest, I wore Large, sometimes XL, to fit ing autographs, like Nureyev. my longish, muscular legs. There was always I grew up managing the sizes and lengths lots of extra material at the top to roll down, of tights, ingrown hair, and finding the best and to keep them up I wore a belt I’d made tights for my body. Mirella men’s tights felt from a short piece of white elastic knotted to- like a gift from heaven, unlike Capezio’s Ba - gether at the ends. -

Take a Look at the Progra

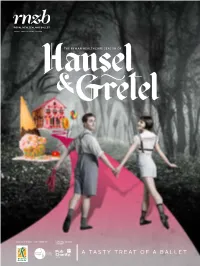

SEASON SPONSOR SUPPORTED BY NATIONAL TOURING PARTNER A TASTY TREAT OF A BALLET ROYAL NEW ZEALAND BALLET CLICK TO EXPLORE Artistic Director Patricia Barker Executive Director Lester McGrath Ballet Masters Clytie Campbell, Laura McQueen Schultz, Nicholas Schultz, Michael Auer (guest) Principals Allister Madin, Paul Mathews, Katharine Precourt, Mayu Tanigaito, Nadia Yanowsky Soloists Sara Garbowski, Kate Kadow, Shaun James Kelly, Fabio Lo Giudice, Massimo Margaria, Katherine Minor, Joseph Skelton Choreography Loughlan Prior Artists Cadence Barrack, Luke Cooper, Rhiannon Fairless, Kiara Flavin, Madeleine Graham, Kihiro Kusukami, Minkyung Music Claire Cowan Lee, Yang Liu*, Nathan Mennis, Olivia Moore, Clare Set and costume design Kate Hawley Schellenberg, Kirby Selchow, Katherine Skelton, Laurynas Assistant set designers Miriam Silvester and Seth Kelly Vėjalis, Leonora Voigtlander, Caroline Wiley, Wan Bin Yuan Lighting Jon Buswell Todd Scholar Teagan Tank Visual effectsPOW Studios Apprentices Georgia Baxter, Ella Chambers, Lara Flannery, Conductor Hamish McKeich Vincent Fraola, Calum Gray, Kaya Weight Orchestra Orchestra Wellington Guests Jamie Delmonte, Tristan Gross, Levi Teachout *On parental leave. CONNECT WITH US rnzb.org.nz Vodafone is proud to keep the Royal New Zealand Ballet facebook.com/nzballet connected, whether we’re in Wellington or out on the road. In twitter.com/nzballet December 2019, Vodafone will be launching the next generation instagram.com/nzballet of mobile technology – 5G. To learn more about what this youtube.com/nzballet means for you and your business visit vodafone.co.nz/5G. Hansel and Gretel drive our story and their ‘ Above all, the story is about Building relationship reflects the ups and downs of overcoming difficult obstacles any good sibling bond. -

—Maverick Hollywood Producer Lawrence Bender Keeps One Eye on the Movies and the Other on the Fate of the Earth

fmIl COUG NTIN TO ZERO —Maverick Hollywood producer LaWRence BendeR keeps one eye on the movies and the other on the fate of the Earth. Lately he has been looking for ways to make nuclear weapons disappear. By LaETITIa CaSh Photography mIChaEL ToDD Photo assistant mErEDITh JENkS Thanks to DaNI Du haDWay n 2003, when Al Gore was touring American university campuses with his global warming slideshow, Lawrence Bender was in the audience, and he walked away feeling he wanted to do something – but what? “I am not a scientist or a politician,” Bender recalls thinking. Sure, he had produced Pulp Fiction, Good Will Hunting, Kill Bill 1 and 2 and other hugely successful Hollywood movies – but what did that matter in the face of the daunting reality of climate change? “I am just one of many billions of people on this planet, but [global warming is one of] Ithe greatest issues facing us in our lifetime. My only thought was: What do I have to contribute towards tackling this?” What he contributed was An Inconvenient Truth, the film version of Gore’s lecture, which Bender produced along with Laurie David and which went on to win Best Documentary at the 2006 Academy Awards. “This was when I first had an inkling I could use movies to make a difference,” he says. Four years on Bender is sitting in his sunlit production suite in Los Angeles discussing a new game-changing documentary, Countdown to Zero, which screened earlier this year at the Sundance s 6 6 Above MAGAZINe FALL 2010 67 A bove core / fmIl ‘Now that the Cold War is over, everyone has forgotten about nuclear weapons.’ and Cannes film festivals.