For Peer Review Only

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marine Science

Western Indian Ocean JOURNAL OF Marine Science Volume 18 | Issue 1 | Jan – Jun 2019 | ISSN: 0856-860X Chief Editor José Paula Western Indian Ocean JOURNAL OF Marine Science Chief Editor José Paula | Faculty of Sciences of University of Lisbon, Portugal Copy Editor Timothy Andrew Editorial Board Lena GIPPERTH Aviti MMOCHI Sweden Tanzania Serge ANDREFOUËT Johan GROENEVELD France Cosmas MUNGA South Africa Kenya Ranjeet BHAGOOLI Issufo HALO Mauritius South Africa/Mozambique Nyawira MUTHIGA Kenya Salomão BANDEIRA Christina HICKS Mozambique Australia/UK Brent NEWMAN Betsy Anne BEYMER-FARRIS Johnson KITHEKA South Africa USA/Norway Kenya Jan ROBINSON Jared BOSIRE Kassim KULINDWA Seycheles Kenya Tanzania Sérgio ROSENDO Atanásio BRITO Thierry LAVITRA Portugal Mozambique Madagascar Louis CELLIERS Blandina LUGENDO Melita SAMOILYS Kenya South Africa Tanzania Pascale CHABANET Joseph MAINA Max TROELL France Australia Sweden Published biannually Aims and scope: The Western Indian Ocean Journal of Marine Science provides an avenue for the wide dissem- ination of high quality research generated in the Western Indian Ocean (WIO) region, in particular on the sustainable use of coastal and marine resources. This is central to the goal of supporting and promoting sustainable coastal development in the region, as well as contributing to the global base of marine science. The journal publishes original research articles dealing with all aspects of marine science and coastal manage- ment. Topics include, but are not limited to: theoretical studies, oceanography, marine biology and ecology, fisheries, recovery and restoration processes, legal and institutional frameworks, and interactions/relationships between humans and the coastal and marine environment. In addition, Western Indian Ocean Journal of Marine Science features state-of-the-art review articles and short communications. -

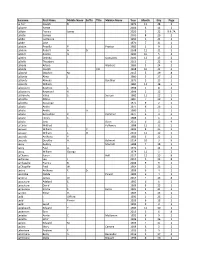

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

525SMT Priority Claimed from 20/12/2011; Application No

Trade Marks Journal No: 1870 , 08/10/2018 Class 12 525SMT Priority claimed from 20/12/2011; Application No. : 85/500,045 ;United States of America 2346046 11/06/2012 BELL HELICOPTER TEXTRON INC. P.O. BOX 482 FORT WORTH, TEXAS 76101, USA MANUFACTURERS AND MERCHANTS A CORPORATION ORGANIZED AND EXISTING UNDER THE LAWS OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE, USA Address for service in India/Agents address: AJAY SAHNI. 14/55, PUNJABI BAGH ( WEST ) NEW DELHI - 110 026. Proposed to be Used DELHI "HELICOPTERS AND STRUCTURAL PARTS THEREFOR" 3102 Trade Marks Journal No: 1870 , 08/10/2018 Class 12 Priority claimed from 02/04/2012; Application No. : 2012-025495 ;Japan 2348297 14/06/2012 NISSAN JIDOSHA KABUSHIKI KAISHA NO. 2, TAKARACHO, KANGAWA-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA-KEN JAPAN MANUFACTURE & MERCHANTS A CORPORATION ,ORGANIZED AND EXISTING UNDER THE LAWS OF JAPAN Address for service in India/Agents address: KOCHHAR & CO TECHNOPOLIS BUILDING, TOWER-B, 3RD FLOOR, SECTOR-54, DLF GOLF COURSE ROAD, GURGOAN-122002. Proposed to be Used DELHI Non-electric prime movers for land vehicles [not including “their parts”]; Shafts, axles or spindles [for land vehicles]; Bearings [for land vehicles]; Shaft couplings or connectors [for land vehicles]; Power transmissions and gearings [for land vehicles]; Shock absorbers [for land vehicles]; Springs [for land vehicles]; Brakes [for land vehicles]; AC motors or DC motors for land vehicles [not including “their parts”]; Automobiles and their parts and fittings; Electric automobiles and their parts and fittings; Fuel cell automobiles and their parts and fittings; all of the above excluding two wheelers and parts thereof. -

Growth Is Dead, Long Live Growth the Quality of Economic Growth and Why It Matters

The Quality of Economic Growth and Why it Matters it Why and Growth Economic of Quality The Growth Live Long Dead, is Growth JICA Research Institute January 2015 Nicolas Meisel Nicolas Kato Hiroshi Haddad Lawrence Growth is Dead, Long Live Growth The Quality of Economic Growth and Why it Matters JICA Research Institute Edited by Lawrence Haddad Hiroshi Kato Nicolas Meisel JICA Research Institute Growth is Dead, Long Live Growth The Quality of Economic Growth and Why it Matters Edited by Lawrence Haddad Hiroshi Kato Nicolas Meisel January 2015 Agence Française de Développement (AFD) Institute of Development Studies (IDS) Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) The views and opinions expressed in the articles contained in this volume do not necessarily represent the official views or positions of the organizations the authors work for or are affiliated with. Agence Française de Développement (AFD) http://www.afd.fr/lang/en/home Institute of Development Studies (IDS) http://www.ids.ac.uk/ Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) http://www.jica.go.jp/english/index.html Haddad, Lawrence, Hiroshi Kato and Nicolas Meisel. 2015. Growth is Dead, Long Live Growth: The Quality of Growth and Why it Matters. Tokyo: JICA Research Institute. Produced by JICA Research Institute http://jica-ri.jica.go.jp/index.html 10-5 Ichigaya Honmura-cho Shinjuku-ku Tokyo 162-8433, JAPAN TEL: +81-3-3269-3374 FAX: +81-3-3269-2054 Email: [email protected] Copyright ©2015 Agence Française de Développement (AFD), Institute of Development Studies (IDS), Japan -

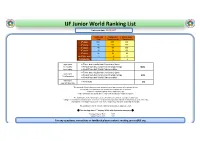

IJF Junior World Ranking List

IJF Junior World Ranking List Latest update: 09/10/2017 Continental Continental World Junior Open Championships Championship 1st place 100 200 500 2nd place 60 120 300 3rd place 40 80 200 5th place 20 40 100 7th place 16 32 80 each fight won 2 6 12 Participation 2 4 look back l Three best results from Continental Open 12 months l Result from last Continental Championships 100% from today l Result from last World Championships l Three best results from Continental Open look back l Result from last Continental Championships 50% 13-24 months l Result from last World Championships look back l All results 0% over 24 months The points for World Championships and Continental Open events will expire as follows: l In the first 12 months after the tournament the points will count 100%. l After 12 months the points will be reduced to 50%. l After 24 months the points will be reduced to 0 and not accounted anymore. The dividing line is the following week (week number) in which the tournament was held. Example: If tournament is held in week 17 of 2014, the points are reduced to half on the beginning of week 18 in 2015 and expired in the beginning of week 18 in 2016. Beginning of the week is defined as Monday. The dividing line for the Continental Championships is always week 26. st The starting date: 1 January 2014 with 0 point for everyone ! Youngest Year of Birth 1997 Oldest Year of Birth 2002 For any questions, corrections or feedback please contact: [email protected] -55 kg IJF Junior World Ranking List 09/10/2017 Total score Ranking FAMILY -

Executive Elections 2021 Voting Register All Staff

Executive Elections 2021 Voting Register All Staff Surname And Forename Department Description (Henry) Hussey, Pamela School Of Nursing Psychotherapy Communit Abahaziova, Eva Finance Office Abdulahovic Smith, Semra Dcu Institute Of Education Office Abgaz, Yalemisew M. School Of Computing Adams, Linda School Of Theology,Philosophy And Music Adelman, Juliana School Of History And Geography Admirand, Peter School Of Theology,Philosophy And Music Afoullouss, Houssaine Salis Ahad, Inam Ul School Of Mechanical Engineering Ahern, Helena Student Support & Development Aherne, Larry Information Systems Services Ahmed Obeidi, Muhannad School Of Mechanical Engineering Áine Costello, Róisín School Of Law & Government Akintola, Philomena Office Of The Chief Operations Officer Al Haj Ali, Motasem Open Education Unit Alakkari, Salaheddin Insight Ali, Fatima Human Resources Alvarez, Paula Salis Anandarajah, Prince School Of Electronic Engineering Anderson, Bradford School Of Theology,Philosophy And Music Andrade, Mario Information Systems Services Andrews, Sinéad Sch Of Inclusive And Special Education Andrieu, Charlotte Nicb Appleby, John School Of Mathematics Arellano Reyes, Ruben Arturo Ncsr Aurand, Joshua School Of Mathematics Ayres, Tony Office Of Vp Academic Affairs Ayub, Hasan School Of Mechanical Engineering Bain, Conor School Of Chemical Sciences Ball, Sophie Research & Innovation Support Bannon, Marcella Presidents Office Barakabitze, Alcardo Adapt Barbali, Brian Information Systems Services Barhoum, Ahmed Ncsr Barker, Jane Estates Office Barr, -

Tropical Legume Trees and Their Soil-Mineral Microbiome: Biogeochemistry and Routes to Enhanced Mineral Access

Tropical legume trees and their soil-mineral microbiome: biogeochemistry and routes to enhanced mineral access A thesis submitted by Dimitar Zdravkov Epihov in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield October 29th, 2018 1 © Copyright by Dimitar Zdravkov Epihov, 2018. All rights reserved. 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my academic superivising team including Professor David J. Beerling and Professor Jonathan R. Leake for their guidance and support throughout my PhD studies as well as the European Research Council (ERC) for funding my project. Secondly, I would like to thank my girlfriend, Gabriela, my parents, Zdravko and Mariyana, and my grandmother Gina, for always believing in me. My biggest gratitude goes for my girlfriend for always putting up with working ridiculous hours and for helping me during field work even if it meant getting stuck in the Australian jungle at night and stumbling across a well-grown python. I would also want to express my thanks to my first ever Biology teacher Mrs Moskova for inspiring and nurturing the interest that grew to be a life-lasting passion, curiousity and love towards all things living. Lastly, I would like to thank Irene Johnson, our laboratory manager and senior technician for always been there for advice, help and general cheering up as well as all other great scientists and collaborators I have had the chance to talk to and work with during my PhD project. I devote this work to a future with more green in it. -

Author Index

AUTHOR INDEX Page Numbers in Italics Refer to References Aarts, L. 416, 447, 1086, 1088, 1174 Ahlstrom, C. 175, 177, 783, 807, 848, Abdel-Aty, M. 357, 377, 1124, 1159 1001, 1002, 1028, 1032 Abdu, R. 66, 80, 485, 502, 750, 780 Ahmad, O. 83 Abdul-Halin, A. 978 Ahmad-Farhan, M. S. 977 A˚berg, L. 398, 408, 425, 450 Ahmed, M. M. 1124, 1159 Abotnes, B. 642, 708 A˚hsberg, E. 797À798, 799, 805, 807, 848 Abouk, R. 776, 780 Ajaiyeoba, A. I. 177 Abou-Zeid, M. 462, 504 Ajzen, I. 109, 111, 125, 396, 447, 462, 502 Abrams, B. S. 34, 178 A˚kerstedt, T. 82, 177, 799, 807, 815, 828, Abramson, Y. 1159 848, 849, 851, 852 Abric, J. C. 123, 127, 467, 505 Aksan, N. 359, 377, 386 Abtahi, S. 843, 848 Albanese, B. 981 Achara, S. 1108, 1159 Albert, G. 778, 780 Adams, B. D. 270, 320 Albert, P. 323 Adams, C. L. 504 Alden, A. 849 Adams, J. 22, 33, 553 Aleardi, M. 508 Adams, S. 776, 780 Alexander, G. J. 1119, 1159, 1161, 1168 Adekoya, B. J. 146, 177 Alexander, J. 107, 130, 847, 851 Adell, E. 1028, 1032 Alexander, K. R. 186, 381 Adepoju, F. G. 177 Alferdinck, J. W. W. M. 1035 Adeyemi, B. 1159 Alicandri, E. 854 Adlaf, E. M. 510 Allen, M. J. 5, 34,141,178, 216, 247, 887, Adler, A. V. 690, 699 892À893, 915 Adminaite, D. 864, 869, 915, 988, 991, Allen Jr., J. A. 162, 179, 379 1028 Allman, R. M. 185 Adriaenssens, G. -

Surname First Name Middle Name Suffix Title Maiden Name Year Month Day Page La Farr Joseph B

Surname First Name Middle Name Suffix Title Maiden Name Year Month Day Page La Farr Joseph B. 1972 11 28 2 Labarre Yvette 2004 6 11 2 LaBate Francis James 2020 5 22 9 & 7A Labate Samuel 2000 8 29 2 Labbe Germaine 1991 1 21 2 Labbe Jane 1970 7 31 1 Labdon Priscilla P. Proctor 1985 1 9 2 Labdon Robert A. Sr. 2008 11 21 2 Labeet Alonzo O. 1990 10 5 2 LaBeet Delinda Gonsalves 2006 12 15 2 LaBelle Theodore L. 2013 1 22 6 Laboda Arlene Wacholz 1985 5 24 2 Laboda Joseph Col. 1968 10 22 2 LaBoeuf Stephen M. 2015 5 29 8 LaBonte Alma J. 1980 5 27 2 LaBonte Almeda Boutilier 1973 3 13 2 LaBonte William 1980 11 18 2 Labossiere Beatrice E. 1998 5 8 2 Labossiere Raymond R. 1999 2 12 2 LaBranche Valea S. Soucey 1982 11 23 2 Labretto Albino 1987 7 29 2 Labretto Guiseppe 1975 9 2 2 Labute Andre 1977 8 26 2 Labute Andre Jr. 1980 2 1 2 Labute Bernadine P. Pommier 1977 3 4 2 Labute Henry C. 1988 4 1 2 Labute Jane Dean 2015 6 12 9 LaCarte Mildred L. Kelloway 1988 12 12 2 Lacasse William Jr. 1992 8 25 2 Lacasse William L. III 2010 11 12 2 Lacerda Anthony P. 1983 3 22 2 Lacerda Dorothy A. Belmont 2014 10 3 9 Lacey Audrey Mitchell 1988 7 18 2 Lacey Paul A. 1972 1 14 2 Lacey William George 1974 11 1 2 LaChance Karen Hall 2017 12 15 8 Lachance Leo J. -

Current Issues in Comparative Education

Current Issues in Comparative Education Volume 15(1) / Fall 2012 • ISSN 1523-1615 • http://www.tc.edu/cice EDUCATION IN SMALL STATES: FRAGILITIES, VULNERABILITIES, AND STRENGTHS Editorial Introduction 5 Re-reading the Anamorphosis of Educational Fragility, Vulnerability, and Strength in Small States Tavis D. Jules, Special Guest Editor Invited Articles: Re-conceptualizing and Re-reading Educational Developments in Small States 14 Meeting the Tests of Time: Small States in the 21st Century Godfrey Baldacchino 26 Learning from Small States for Post-2015 Educational and International Development Michael Crossley and Terra Sprague Fragility in Small States: A Community-based Perspective 41 A Broader Definition of Fragility: The Communities and Schools of Brazil’s Favelas Rolf Straubhaar 52 How to Make the Small Indigenous Cultures Bloom? Special Traits of Sámi Pedagogy in Finland Pigga Keskitalo, Satu Uusiautti, and Kaarina Määttä Vulnerability in Small States: An Institutional Perspective on Small Jurisdiction and Small Assemblages 64 Explaining Whole System Reform in Small States: The Case of the Trinidad and Tobago Secondary Education Modernization Program Jerome De Lisle 83 Small States and Big Institutions: USAID and Education Policy Formation in El Salvador D. Brent Edwards Jr. Education Reform in Small States: A Comparative Perspective 100 Small State, Large World, Global University? Comparing Ascendant National Universities in Luxembourg and Qatar Justin J.W. Powell 114 Overcoming Smallness through Education Development: A Comparative Analysis of Jamaica and Singapore Richard O. Welsh 132 Internationalization of Higher Education in Post-Soviet Small States: Realities and Perspectives of Moldova Valentyna Kushnarenko and Ludmila Cojocari Case Studies of Educational Reform in Small States: A Cultural Perceptive 145 Inclusive Education in Bhutan: A Small State with Alternative Priorities Matthew J. -

Font Selection

JJ IIIIII SSSSSS 0000 3333 555555 888 EEEEEE JJ IIIIII SS SS 0 00 3 3 5 8 8 EE JJ II SSS 0 0 0 33 55555 888 EEEEE JJ JJ II SSS 0 0 0 3 5 8 8 EE JJJJJJ IIIIII SS SS 00 0 3 3 5 8 8 EEEEEE JJJJ IIIIII SSSSSS 0000 3333 55555 888 EEEEEE JJ 0000 0000 0000 777777 6 4 3333 JJ 0 00 0 00 0 00 7 6 44 3 3 JJ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 7 6 666 4 4 33 JJ JJ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 7 66 6 444444 3 JJJJJJ 00 0 00 0 00 0 7 6 6 4 3 3 JJJJ 0000 0000 0000 7 6666 4 3333 * START RMTSCPE SC7053 FR SCBI ROOM C11A 07.57.53 AM 24 MAY 2021 * * START RMTSCPE SC7053 FR SCBI ROOM C11A 07.57.53 AM 24 MAY 2021 * * START RMTSCPE SC7053 FR SCBI ROOM C11A 07.57.53 AM 24 MAY 2021 * * START RMTSCPE SC7053 FR SCBI ROOM C11A 07.57.53 AM 24 MAY 2021 * * START RMTSCPE SC7053 FR SCBI ROOM C11A 07.57.53 AM 24 MAY 2021 * * START RMTSCPE SC7053 FR SCBI ROOM C11A 07.57.53 AM 24 MAY 2021 * * START RMTSCPE SC7053 FR SCBI ROOM C11A 07.57.53 AM 24 MAY 2021 * * START RMTSCPE SC7053 FR SCBI ROOM C11A 07.57.53 AM 24 MAY 2021 * * START RMTSCPE SC7053 FR SCBI ROOM C11A 07.57.53 AM 24 MAY 2021 * *2 J0007643 JIS0358E TPSCPE H111 ACCTNG PR17 JIS0358E J0007643 2* BMIRRPT CITY & COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO COURT MANAGEMENT SYSTEM REPORT # 7053 RUN 05/24/21 @ 07:57 PAGE 1 *------------------------------------------------------------------------------- (CC7053. -

IDRC Davos 2010 Participants Here

IDRC 2010 participants.qxp 26.5.2010 12:06 Uhr Seite 1 INTERNATIONAL DISASTERANDRISK CONFERENCE IDRC DAVOS 2010 PARTICIPANTS LIST May 30–June 3, 2010 Davos, Switzerland www.grforum.org Last name First name Affiliation ALBANIA Ahmetaj Luan AAOH Bioplant Albania ALGERIA Allia Khedidja USTHB - MESRS Benouar Djillali University of Science and Technology Houari Boumediene (USTHB) Kouici Lakhdar University Talibi Mohamed ANRH Zegrar Ahmed Centre of spaces techniques ANDORRA Torrebadella Joan EUROCONSULT AUSTRALIA Roman Carolina Ester Monash University Shrestha Binod University Technology Sydney Zoleta-Nantes Doracie Baldovino Australian National Uniersity AUSTRIA Aubrecht Christoph AIT Austrian Institute of Technology GmbH Botez Oana Casti John Louis iiasa De Luis Juan Jose OSCE Fazeliniaki Mohsen FH Technikum Wien Hochrainer Stefan IIASA - International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis Mair Rudi Government of the Tyrol Neuhold Clemens University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences, Vienna Roy Dulal Chandra University of Salzburg Veulliet Eric alpS - Center for Natural Hazard and Risk Management Von Winterfeldt Detlof International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis Walder Ulrich Graz University of Technology BANGLADESH Ahammad Ronju Shushilan Alam Md. Edris University of Chittagong Al-Amin Mohammad progress holding limited Baidya Haragobinda Minority Self EmpowermentFoundation (MSEF) Bakuluzzaman Mustafa Shushilan Baten Mohammed Abdul Unnayan Onneshan-The Innovators Biswas A. K. M. Abdul Ahad Patuakhali Science and Technology University Das Dilip Kumar Design Bangladesh Datta Avinoy Design Bangladesh Datta Gobinda Design Bangladesh Haq Rezaul A.H.M wetland resouce development society Hasan Mohammad Tareq Unnayan Onneshan Hossain Miah Ali Independent University, Bangladesh Islam Md. Mahfuzul Association for Rural Development (ARD) Islam Mahmudul Comprehensive Disaster Mnagement Programme Islam Asraful Design Bangladesh Khan Asaduzzaman Design Bangladesh Mallick Md.