EUI Working Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Focusthe Barcelona Centre for International Affairs Brief

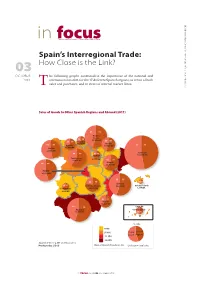

CIDOB • Barcelona Centre for International 2012 for September Affairs. Centre CIDOB • Barcelona in focusThe Barcelona Centre for International Affairs Brief Spain’s Interregional Trade: 03 How Close is the Link? OCTOBER he following graphs contextualise the importance of the national and 2012 international market for the 17 dif ferent Spanish regions, in terms of both T sales and purchases, and in terms of internal market flows. Sales of Goods to Other Spanish Regions and Abroad (2011) 46 54 Basque County 36 64 45,768 M€ 33 67 Cantabria 45 55 7,231 M€ Navarre 54 46 Asturias 17,856 M€ 53 47 Galicia 11,058 M€ 32,386 M€ 40 60 31 69 Catalonia La Rioja 104,914 M€ Castile-Leon 4,777 M€ 30,846 M€ 39 61 Aragon 54 46 23,795 M€ Madrid 45,132 M€ 45 55 22 78 5050 Valencia 29 71 Castile-La Mancha 44,405 M€ Balearic Islands Extremaura 18,692 M€ 1,694 M€ 4,896 M€ 39 61 Murcia 14,541 M€ 44 56 4,890 M€ Andalusia Canary Islands 52,199 M€ 49 51 % Sales 0-4% 5-10% To the Spanish World Regions 11-15% 16-20% Source: C-Intereg, INE and Datacomex Produced by: CIDOB Share of Spanish Population (%) Circle Size = Total Sales in focus CIDOB 03 . OCTOBER 2012 CIDOB • Barcelona Centre for International 2012 for September Affairs. Centre CIDOB • Barcelona Purchase of Goods From Other Spanish Regions and Abroad (2011) Basque County 28 72 36 64 35,107 M€ 35 65 Asturias Cantabria Navarre 11,580 M€ 55 45 6,918 M€ 14,914 M€ 73 27 Galicia 29 71 25,429 M€ 17 83 Catalonia Castile-Leon La Rioja 97,555 M€ 34,955 M€ 29 71 6,498 M€ Aragon 67 33 26,238 M€ Madrid 79,749 M€ 44 56 2 78 Castile-La Mancha Valencia 19 81 12 88 23,540 M€ Extremaura 49 51 45,891 M€ Balearic Islands 8,132 M€ 8,086 M€ 54 46 Murcia 18,952 M€ 56 44 Andalusia 52,482 M€ Canary Islands 35 65 13,474 M€ Purchases from 27,000 to 31,000 € 23,000 to 27,000 € Rest of Spain 19,000 to 23,000 € the world 15,000 to 19,000 € GDP per capita Circle Size = Total Purchase Source: C-Intereg, Expansión and Datacomex Produced by: CIDOB 2 in focus CIDOB 03 . -

Presentation by Chunta Aragonesista (CHA) on the Situation of the Aragonese Minority Languages (Aragonese and Catalan)

Presentation by Chunta Aragonesista (CHA) on the situation of the Aragonese minority languages (Aragonese and Catalan) European Parliament Intergroup on Traditional Minorities, National Communities and Languages Strasbourg, 24 May 2012 Aragon is one of the historical nations on which the current Spanish State was set up. Since its origins back in the 9 th century in the central Pyrenees, two languages were born and grew up on its soil: Aragonese and Catalan (the latter originated simultaneously in Catalonia as well as in some areas that have always belonged to Aragon). Both languages expanded Southwards from the mountains down to the Ebro basin, Iberian mountains and Mediterranean shores in medieval times, and became literary languages by their use in the court of the Kings of Aragon, who also were sovereigns of Valencia, Catalonia and Majorca. In the 15 th century a dynastic shift gave the Crown of Aragon to a Castilian prince. The new reigning family only expressed itself in Castilian language. That fact plus the mutual influences of Castilian and Aragonese through their common borders, as well as the lack of a strong linguistic awareness in Aragon facilitated a change in the cultural trends of society. From then on the literary and administrative language had to be Castilian and the old Aragonese and Catalan languages got relegated in Aragon mostly to rural areas or the illiterate. That process of ‘glottophagy’ or language extinction sped up through the 17 th and 18 th centuries, especially after the conquest of the country by the King Philip of Bourbon during the Spanish War of Succession and its annexation to Castile. -

The Beginning of the Neolithic in Andalusia

Quaternary International xxx (2017) 1e21 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint The beginning of the Neolithic in Andalusia * Dimas Martín-Socas a, , María Dolores Camalich Massieu a, Jose Luis Caro Herrero b, F. Javier Rodríguez-Santos c a U.D.I. de Prehistoria, Arqueología e Historia Antigua (Dpto. Geografía e Historia), Universidad de La Laguna, Campus Guajara, 38071 Tenerife, Spain b Dpto. Lenguajes y Ciencias de la Computacion, Universidad de Malaga, Complejo Tecnologico, Campus de Teatinos, 29071 Malaga, Spain c Instituto Internacional de Investigaciones Prehistoricas de Cantabria (IIIPC), Universidad de Cantabria. Edificio Interfacultativo, Avda. Los Castros, 52. 39005 Santander, Spain article info abstract Article history: The Early Neolithic in Andalusia shows great complexity in the implantation of the new socioeconomic Received 31 January 2017 structures. Both the wide geophysical diversity of this territory and the nature of the empirical evidence Received in revised form available hinder providing a general overview of when and how the Mesolithic substrate populations 6 June 2017 influenced this process of transformation, and exactly what role they played. The absolute datings Accepted 22 June 2017 available and the studies on the archaeological materials are evaluated, so as to understand the diversity Available online xxx of the different zones undergoing the neolithisation process on a regional scale. The results indicate that its development, initiated in the middle of the 6th millennium BC and consolidated between 5500 and Keywords: Iberian Peninsula 4700 cal. BC, is parallel and related to the same changes documented in North Africa and the different Andalusia areas of the Central-Western Mediterranean. -

Cantabria Y Asturias Seniors 2016·17

Cantabria y Asturias Seniors 2016·17 7 días / 6 noches Hotel Zabala 3* (Santillana del Mar) € Hotel Norte 3* (Gijón) desde 399 Salida: 11 de junio Precio por persona en habitación doble Suplemento Hab. individual: 150€ ¡TODO INCLUIDO! 13 comidas + agua/vino + excursiones + entradas + guías ¿Por qué reservar este viaje? ¿Quiere conocer Cantabria y Asturias? En nuestro circuito Reserve por sólo combinamos lo mejor de estas dos comunidades para que durante 7 días / 6 noches conozcas a fondo los mejores rincones de la geografía. 50 € Itinerario: Incluimos: DÍA 1º. BARCELONA – CANTABRIA • Asistencia por personal de Viajes Tejedor en el punto de salida. Salida desde Barcelona. Breves paradas en ruta (almuerzo en restaurante incluido). • Autocar y guía desde Barcelona y durante todo el recorrido. Llegada al hotel en Cantabria. Cena y alojamiento. • 3 noches de alojamiento en el hotel Zabala 3* de Santillana del Mar y 2 noches en el hotel Norte 3* de Gijón. DÍA 2º. VISITA DE SANTILLANA DEL MAR y COMILLAS – VISITA DE • 13 comidas con agua/vino incluido, según itinerario. SANTANDER • Almuerzos en ruta a la ida y regreso. Desayuno. Seguidamente nos dirigiremos a la localidad de Santilla del Mar. Histórica • Visitas a: Santillana del Mar, Comillas, Santander, Santoña, Picos de Europa, Potes, población de gran belleza, donde destaca la Colegiata románica del S.XII, declarada Oviedo, Villaviciosa, Lastres, Tazones, Avilés, Luarca y Cudillero. Monumento Nacional. Las calles empedradas y las casas blasonadas, configuran un paisaje • Pasaje de barco de Santander a Somo. urbano de extraordinaria belleza. Continuaremos viaje a la cercana localidad de Comillas, • Guías locales en: Santander, Oviedo y Avilés. -

To the West of Spanish Cantabria. the Palaeolithic Settlement of Galicia

To the West of Spanish Cantabria. The Palaeolithic Settlement of Galicia Arturo de Lombera Hermida and Ramón Fábregas Valcarce (eds.) Oxford: Archaeopress, 2011, 143 pp. (paperback), £29.00. ISBN-13: 97891407308609. Reviewed by JOÃO CASCALHEIRA DNAP—Núcleo de Arqueologia e Paleoecologia, Faculdade de Ciências Humanas e Sociais, Universidade do Algarve, Campus Gambelas, 8005- 138 Faro, PORTUGAL; [email protected] ompared with the rest of the Iberian Peninsula, Galicia investigation, stressing the important role of investigators C(NW Iberia) has always been one of the most indigent such as H. Obermaier and K. Butzer, and ending with a regions regarding Paleolithic research, contrasting pro- brief presentation of the projects that are currently taking nouncedly with the neighboring Cantabrian rim where a place, their goals, and auspiciousness. high number of very relevant Paleolithic key sequences are Chapter 2 is a contribution of Pérez Alberti that, from known and have been excavated for some time. a geomorphological perspective, presents a very broad Up- This discrepancy has been explained, over time, by the per Pleistocene paleoenvironmental evolution of Galicia. unfavorable geological conditions (e.g., highly acidic soils, The first half of the paper is constructed almost like a meth- little extension of karstic formations) of the Galician ter- odological textbook that through the definition of several ritory for the preservation of Paleolithic sites, and by the concepts and their applicability to the Galician landscape late institutionalization of the archaeological studies in supports the interpretations outlined for the regional inter- the region, resulting in an unsystematic research history. land and coastal sedimentary sequences. As a conclusion, This scenario seems, however, to have been dramatically at least three stadial phases were identified in the deposits, changed in the course of the last decade. -

Second-Order Elections: Everyone, Everywhere? Regional and National Considerations in Regional Voting

Liñeira, R. (2016) Second-order elections: everyone, everywhere? Regional and national considerations in regional voting. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 46(4), pp. 510- 538. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/219966/ Deposited on: 15 July 2020 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Second-order Elections: Everyone, Everywhere? Regional and National Considerations in Regional Voting Robert Liñeira University of Edinburgh [email protected] Abstract: Vote choice in regional elections is commonly explained as dependent on national politics and occasionally as an autonomous decision driven by region-specific factors. However, few arguments and little evidence have been provided regarding the determinants that drive voters’ choices to one end or the other of this dependency-autonomy continuum. In this article we claim that contextual and individual factors help to raise (or lower) the voters’ awareness of their regional government, affecting the scale of considerations (national or regional) they use to cast their votes at regional elections. Using survey data from regional elections in Spain, we find that voters’ decisions are more autonomous from national politics among the more politically sophisticated voters, among those who have stronger feelings of attachment to their region, and in those contexts in which the regional incumbent party is different from the national one. In their landmark article Reif and Schmitt (1980) drew a distinction between first and second- order elections. -

Chapter 24. the BAY of BISCAY: the ENCOUNTERING of the OCEAN and the SHELF (18B,E)

Chapter 24. THE BAY OF BISCAY: THE ENCOUNTERING OF THE OCEAN AND THE SHELF (18b,E) ALICIA LAVIN, LUIS VALDES, FRANCISCO SANCHEZ, PABLO ABAUNZA Instituto Español de Oceanografía (IEO) ANDRE FOREST, JEAN BOUCHER, PASCAL LAZURE, ANNE-MARIE JEGOU Institut Français de Recherche pour l’Exploitation de la MER (IFREMER) Contents 1. Introduction 2. Geography of the Bay of Biscay 3. Hydrography 4. Biology of the Pelagic Ecosystem 5. Biology of Fishes and Main Fisheries 6. Changes and risks to the Bay of Biscay Marine Ecosystem 7. Concluding remarks Bibliography 1. Introduction The Bay of Biscay is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean, indenting the coast of W Europe from NW France (Offshore of Brittany) to NW Spain (Galicia). Tradition- ally the southern limit is considered to be Cape Ortegal in NW Spain, but in this contribution we follow the criterion of other authors (i.e. Sánchez and Olaso, 2004) that extends the southern limit up to Cape Finisterre, at 43∞ N latitude, in order to get a more consistent analysis of oceanographic, geomorphological and biological characteristics observed in the bay. The Bay of Biscay forms a fairly regular curve, broken on the French coast by the estuaries of the rivers (i.e. Loire and Gironde). The southeastern shore is straight and sandy whereas the Spanish coast is rugged and its northwest part is characterized by many large V-shaped coastal inlets (rias) (Evans and Prego, 2003). The area has been identified as a unit since Roman times, when it was called Sinus Aquitanicus, Sinus Cantabricus or Cantaber Oceanus. The coast has been inhabited since prehistoric times and nowadays the region supports an important population (Valdés and Lavín, 2002) with various noteworthy commercial and fishing ports (i.e. -

Document Downloaded From: the Final Publication Is Available At

Document downloaded from: http://hdl.handle.net/10459.1/67539 The final publication is available at: https://doi.org/10.1075/lplp.00045.tor © John Benjamins Publishing, 2019 The Legal Rights of Aragonese-Speaking Schoolchildren: The Current State of Aragonese Language Teaching in Aragon (Spain) Aragon is an autonomous community within Spain where, historically, three languages are spoken: Aragonese, Catalan, and Castilian Spanish. Both Aragonese and Catalan are minority and minoritised languages within the territory, while Castilian Spanish, the majority language, enjoys total legal protection and legitimation. The fact that we live in the era of the nation-state is crucial for understanding endangered languages in their specific socio-political context. This is why policies at macro-level and micro-level are essential for language maintenance and equality. In this article, we carry out an in-depth analysis of 57 documents: international and national legal documents, education reports, and education curricula. The aims of the paper are: 1) to analyse the current state of Aragonese language teaching in primary education in Aragon, and 2) to suggest solutions and desirable policies to address the passive bilingualism of Aragonese- speaking schoolchildren. We conclude that the linguistic diversity of a trilingual autonomous community is not reflected in the real life situation. There is also a need to Comentado [FG1]: Syntax unclear, meaning ambiguous implement language policies (bottom-up and top-down initiatives) to promote compulsory education in a minoritised language. We therefore propose a linguistic model that capitalises all languages. This study may contribute to research into Aragonese- Comentado [FG2]: Letters can be capitalized, but not languages. -

Working Papers in Economic History the Roots of Land Inequality in Spain

The roots of land inequality in Spain Francisco J. Beltrán Tapia, Alfonso Díez-Minguela, Julio Martinez-Galarraga, Daniel A. Tirado-Fabregat (Universitat de València) Working Papers in Economic History 2021-01 ISSN: 2341-2542 Serie disponible en http://hdl.handle.net/10016/19600 Web: http://portal.uc3m.es/portal/page/portal/instituto_figuerola Correo electrónico: [email protected] Creative Commons Reconocimiento- NoComercial- SinObraDerivada 3.0 España (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 ES) The roots of land inequality in Spain Francisco J. Beltrán Tapia (Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU) Alfonso Díez-Minguela (Universitat de València) Julio Martinez-Galarraga (Universitat de València) Daniel A. Tirado-Fabregat (Universitat de València) Abstract There is a high degree of inequality in land access across Spain. In the South, and in contrast to other areas of the Iberian Peninsula, economic and political power there has traditionally been highly concentrated in the hands of large landowners. Indeed, an unequal land ownership structure has been linked to social conflict, the presence of revolutionary ideas and a desire for agrarian reform. But what are the origins of such inequality? In this paper we quantitatively examine whether geography and/or history can explain the regional differences in land access in Spain. While marked regional differences in climate, topography and location would have determined farm size, the timing of the Reconquest, the expansion of the Christian kingdoms across the Iberian Peninsula between the 9th and the 15th centuries at the expense of the Moors, influenced the type of institutions that were set up in each region and, in turn, the way land was appropriated and distributed among the Christian settlers. -

33 the Radiocarbon Chronology of El Mirón Cave

RADIOCARBON, Vol 52, Nr 1, 2010, p 33–39 © 2010 by the Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of the University of Arizona THE RADIOCARBON CHRONOLOGY OF EL MIRÓN CAVE (CANTABRIA, SPAIN): NEW DATES FOR THE INITIAL MAGDALENIAN OCCUPATIONS Lawrence Guy Straus1,2 • Manuel R González Morales2 ABSTRACT. Three additional radiocarbon assays were run on samples from 3 levels lying below the classic (±15,500 BP) Lower Cantabrian Magdalenian horizon in the outer vestibule excavation area of El Mirón Cave in the Cantabrian Cordillera of northern Spain. Although the central tendencies of the new dates are out of stratigraphic order, they are consonant with the post-Solutrean, Initial Magdalenian period both in El Mirón and in the Cantabrian region, indicating a technological transition in preferred weaponry from foliate and shouldered points to microliths and antler sagaies between about 17,000–16,000 BP (uncalibrated), during the early part of the Oldest Dryas pollen zone. Now with 65 14C dates, El Mirón is one of the most thor- oughly dated prehistoric sites in western Europe. The until-now poorly dated, but very distinctive Initial Cantabrian Magdale- nian lithic artifact assemblages are briefly summarized. INTRODUCTION El Mirón Cave is located in the upper valley of the Asón River in eastern Cantabria Province in northern Spain, about 100 m up from the valley floor on the steep western face of a mountain in the second foothill range of the Cantabrian Cordillera, about halfway between the cities of Santander and Bilbao. The site location in the town of Ramales de la Victoria (431448N, 3275W) is 260 m above present sea level, and about 20 km from the present shore of the Bay of Biscay (and about 25–30 km from the Tardiglacial shore). -

Local Politics (1977-1983)

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Santa Coloma de Gramenet : The Transformation of Leftwing Popular Politics in Spain (1968- 1986) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7t53c8gb Author Davis, Andrea Rebecca Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Santa Coloma de Gramenet: The Transformation of Leftwing Popular Politics in Spain (1968-1986) A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Andrea Rebecca Davis Committee in charge: Professor Pamela Radcliff, Chair Professor Frank Biess Professor Luis Martín-Cabrera Professor Patrick Patterson Professor Kathryn Woolard 2014 Copyright Andrea Rebecca Davis, 2014 All rights reserved. Signature Page The Dissertation of Andrea Rebecca Davis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii DEDICATION To the memory of Selma and Sidney Davis iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ...................................................................................................................iii -

Cómo Citar El Artículo Número Completo Más Información Del

Palabra Clave ISSN: 0122-8285 Universidad de La Sabana Reguero-Sanz, Itziar; Martín-Jiménez, Virginia Programas matinales televisivos: un análisis cuantitativo de las entrevistas a políticos en TVE y Antena 3* Palabra Clave, vol. 23, núm. 1, e2315, 2020, Enero-Marzo Universidad de La Sabana DOI: https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2020.23.1.5 Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=64962833005 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Redalyc Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Programas matinales televisivos: un análisis cuantitativo de las entrevistas a políticos en TVE y Antena 3* Itziar Reguero-Sanz1 Virginia Martín-Jiménez2 Recibido: 02/04/2019 Enviado a pares: 03/04/2019 Aprobado por pares: 29/08/2019 Aceptado: 06/09/2019 DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2020.23.1.5 Para citar este artículo/to reference this article/para citar este artigo Reguero-Sanz, I. y Martín-Jiménez, V. (2020). Programas matinales televisivos: un análisis cuantitativo de las entrevistas a políticos en TVE y Antena 3. Palabra Clave, 23(1), e2315. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2020.23.1.5 Resumen Este artículo analiza los programas matinales de entrevistas y debates de Te- levisión Española (TVE) y Antena 3, emitidos entre 1997 y 2006, en una doble vertiente. En primer lugar, se lleva a cabo un examen cualitativo de la trayectoria de Los desayunos, El primer café, La respuesta y Ruedo ibérico y de la situación empresarial y política de las cadenas que los emitían.