Education, Learning and Community in New Earswick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Earswick Newsletter March /April 2020

Folk Hall a place for meeting New Earswick Newsletter March /April 2020 p1 New Earswick Post Office at the Folk Hall Opening hours: Monday to Friday 9am-6pm Saturday 9am-1.30pm Use us for: • Cash withdrawals (no charges) • Stamps and postal services • Cash and Cheque deposits • Postal Orders • Paystation Gas and Electric Key/Card top up (not paypoint unfortunately) • Bill payments • Travel money and money card order for up to eighteen currencies • Mobile top-ups • One 4 All Gift Cards • Greetings cards, gift wrap and stationery Folk Hall cafe Current opening hours Monday to Saturday 9am to 3pm Teas and coffees • Cold drinks • Hot meals • Melt in the mouth panini Cakes and scones Eat in or take-away p2 Folk Hall – a place for meeting In 2019, children’s school holiday activities went from strength to strength and here’s what some people had to say about it… *We have really enjoyed today, very well ran and food was a bonus! More days like this would be great *It is good, don’t improve nothing *I had a lovely time and it was fun. It was a really nice dinner. You don’t need anything improving *We have had a lovely time playing and lunch was fab. Thank you *Lovely Easter activities for the children. They really enjoyed it. Was a really nice idea making pasta for the children also. Great place to visit Watch this space or follow the New Earswick Folk Hall Facebook page to see what we’ve got planned for 2020! p3 Fodder and Forage veg boxes and flowers Hello again! We're settling in at Fodder&Forage, it's been wonderful to see so many of you visiting us throughout our first couple of months. -

Report on the Second York Schools Science Quiz on Thursday 12 March, Thirteen Schools from in and Around York Came Together

Report on the Second York Schools Science Quiz On Thursday 12 March, thirteen schools from in and around York came together for the second York Schools Science Quiz. Twenty two school teams competed along with four teacher teams (put together from the teachers who brought the pupils along from the various schools) for the trophies and prizes. Each team consisted of two Lower Sixth and two Fifth Form pupils or four Fifth Form pupils for those schools without Sixth Forms. The schools represented were Manor CE School, Canon Lee School, The Joseph Rowntree School, Huntington School, Archbishop Holgate’s School, Fulford School, All Saints School, Millthorpe School, St Peter’s School, Bootham School, The Mount School, Selby High School and Scarborough College. The event took place as part of the York ISSP and also the York Schools Ogden Partnership, with a large thank you to the Royal Society of Chemistry and the Institute of Physics for some of the prizes, the Rotary Club of York Vikings for the water bottles and the Ogden Trust for the 8 GB memory sticks and Amazon Voucher prizes. The quiz was put together and presented by Sarah McKie, who is the Head of Biology at St Peter’s School, and consisted of Biology, Chemistry and Physics rounds alongside an Observation Challenge and a Hitting the Headlines round amongst others. At the end of the quiz the teams waited with bated breath for the results to be announced. It turned out that three teams were tied for second place, so a tie breaker was needed to separate them. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939 Jennings, E. How to cite: Jennings, E. (1965) The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9965/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Abstract of M. Ed. thesis submitted by B. Jennings entitled "The Development of Education in the North Riding of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939" The aim of this work is to describe the growth of the educational system in a local authority area. The education acts, regulations of the Board and the educational theories of the period are detailed together with their effect on the national system. Local conditions of geograpliy and industry are also described in so far as they affected education in the North Riding of Yorkshire and resulted in the creation of an educational system characteristic of the area. -

JRS Connect Magazine Issue 1 V4

Issue 1 Dec 2013 “ “ working together to achieve success Connect the right school to grow in SPORTING SUCCESS! U16 NETBALLERS FINISH THE AREA ROUND UNDEFEATED! //page 7 FRENCH EXCHANGE... COA: Ella Hutchinson DRAMA: Lucky number 7 Also in this issue //page 4 getting her award //page 5 in the Vaudeville //page 6 Connect Magazine - Issue 1 THE JOSEPH ROWNTREE SCHOOL THE JOSEPH ROWNTREE SCHOOL Issue 1 - Connect Magazine The Headteacher Chocolate Box Challenge A warm welcome to the first edition of creative flair or making a difference in the school and 2013 ‘Connect’ - The Joseph Rowntree School local communities, The Joseph Rowntree students magazine. In it you will find a demonstrate a really positive attitude to For the second year running, NYBEP and Nestlé have life as well as making the most of their run a city-wide enterprise competition for Key Stage 4 celebration of all the great potential. things that are going on in our and 5 students based around the idea of developing a box of chocolates within the guidance of a particular school – it is a nice problem The next edition of ‘Connect’ will be brief. The theme this year was to celebrate 150 years published later in the academic year. It will to have when there is more of Nestlé as a company. material than space on the showcase more elements of life at our school – a reflection of the talents and hard pages for a magazine, and work of our students and staff, and the The challenge was delivered in school across the Enterprise shows how much is going on continued support of parents and the local groups in Year 10. -

Applying for a School Place for September 2018

Guide for Parents Applying for a school place for September 2018 City of York Council | School Services West Offices, Station Rise, York, YO1 6GA 01904 551 554 | [email protected] www.york.gov.uk/schools | @School_Services Dear Parent/Carer, and those with siblings already at a school, inevitably there are times when Every year the Local Authority provides parental preferences do not equate to places in schools for children in the City the number of available local places. of York. This guide has been put together to explain how we can help you through Please take the time to read this guide the school admissions process and to let carefully and in particular, take note of you know what we do when you apply the key information and the for a school place for your child and what oversubscription criteria for the schools we ask you to do. that you are interested in. It contains details of admissions policies and Deciding on your preferred schools for procedures and the rules that admissions your child is one of the most important authorities must follow. Reading this decisions that you will make as a guide before making an application may parent/carer. This guide contains some prevent misunderstanding later. If after information about our schools and our considering the information available services. We recommend that you visit here you need more information, please schools on open evenings or make an contact the School Services team who will appointment at a school prior to making be happy to assist you further. an application. -

Land Off Avon Drive, Huntington, York, Yo32 9Ya Application Ref: 15/00798/Outm

Our ref: APP/C2741/W/16/3149489 James Hobson White Young Green Rowe House 10 East Parade Harrogate HG1 5LT 21 April 2017 Dear Sirs TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990 – SECTION 78 APPEAL MADE BY PILCHER HOMES LTD LAND OFF AVON DRIVE, HUNTINGTON, YORK, YO32 9YA APPLICATION REF: 15/00798/OUTM 1. I am directed by the Secretary of State to say that consideration has been given to the report of Pete Drew BSc (Hons), DipTP (Dist), MRTPI, who held a public local inquiry from 6-9 December 2016 into your client’s appeal against the decision of City of York Council (“the Council”) to refuse planning permission for your client’s outline application for planning permission for the proposed erection of 109 dwellings, in accordance with application ref: 15/00798/OUTM, dated 9 April 2015, on land off Avon Drive, Huntington, York. 2. On 3 August 2016, this appeal was recovered for the Secretary of State's determination, in pursuance of section 79 of, and paragraph 3 of Schedule 6 to, the Town and Country Planning Act 1990, because it involves proposals for significant development in the Green Belt. Inspector’s recommendation and summary of the decision 3. The Inspector recommended that the appeal be dismissed. For the reasons given below, the Secretary of State agrees with the Inspector’s recommendation, dismisses the appeal and refuses planning permission. A copy of the Inspector’s report (IR) is enclosed. All references to paragraph numbers, unless otherwise stated, are to that report. Procedural matters 4. The Secretary of State has considered carefully the Inspector’s analysis and assessment of procedural matters at IR6 and IR202-208. -

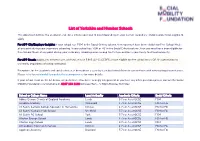

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools This document outlines the academic and social criteria you need to meet depending on your current secondary school in order to be eligible to apply. For APP City/Employer Insights: If your school has ‘FSM’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling. If your school has ‘FSM or FG’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling or be among the first generation in your family to attend university. For APP Reach: Applicants need to have achieved at least 5 9-5 (A*-C) GCSES and be eligible for free school meals OR first generation to university (regardless of school attended) Exceptions for the academic and social criteria can be made on a case-by-case basis for children in care or those with extenuating circumstances. Please refer to socialmobility.org.uk/criteria-programmes for more details. If your school is not on the list below, or you believe it has been wrongly categorised, or you have any other questions please contact the Social Mobility Foundation via telephone on 0207 183 1189 between 9am – 5:30pm Monday to Friday. School or College Name Local Authority Academic Criteria Social Criteria Abbey Grange Church of England Academy Leeds 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Airedale Academy Wakefield 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints Catholic College Specialist in Humanities Kirklees 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints' Catholic High -

Making a Sustainable Community: Life in Derwenthorpe, York, 2012–2018

Making a sustainable community: life in Derwenthorpe, York, 2012–2018 by Deborah Quilgars, Alison Dyke, Alison Wallace and Sarah West This report presents the results of a six-year evaluation of Derwenthorpe, an urban extension of about 500 homes in York, developed by the Joseph Rowntree Housing Trust (JRHT) and David Wilson Homes. The research documented the extent to which it met its aims to create a socially and environmentally sustainable community ‘fit for the 21st century’. Making a sustainable community: life in Derwenthorpe, York, 2012– 2018 Deborah Quilgars, Alison Dyke, Alison Wallace and Sarah West This report presents the results of a six-year evaluation of Derwenthorpe, an urban extension of about 500 homes in York, developed by the Joseph Rowntree Housing Trust (JRHT) and David Wilson Homes. The research documented the extent to which it met its aims to create a socially and environmentally sustainable community ‘fit for the 21st century’. The research demonstrated that mainstream housing developers can successfully deliver sustainable homes and communities at scale, in particular delivering high-quality living environments. However, technical build issues and differential buy-in from residents means that environmental and social measures need to be built into the model as far as possible from the outset. The research involved an environmental survey and longitudinal qualitative interviews to document residents’ experiences over the period 2012–2018. It also compared Derwenthorpe with three other sustainable housing developments in England. Actions • Greater emphasis on the design, space standards and aesthetics of new developments should be incorporated into Government-level directives. • Housing providers must work with resident groups to set up inclusive governance structures to promote the long-term social sustainability of communities. -

Housing with JRHT a Guide for Residents HOUSING with JRHT LEAFLET 01

LEAFLET 01 Housing with JRHT A guide for residents HOUSING WITH JRHT LEAFLET 01 This leaflet contains information and 1. The types and sizes of guidance on: homes we offer and where 1. The types and sizes of homes we offer and where they are located they are located 2. Our allocations policy What type of homes do we have? 3. What you will be expected to pay per property type We have flats, houses, and bungalows 4. Other organisations who provide suitable for: accommodation • Single people • Couples • Families with children • Older people – if you have retired we also have sheltered housing and ‘extra care’ housing What size of homes do we have? We have: • Studio apartments • One and two bedroom flats • Two, three, and some four and five bedroom houses • One, two and three bedroom bungalows • Two and three bedroom maisonettes PAGE 2 LEAFLET 01 HOUSING WITH JRHT Where are these homes? Rented Property Areas Streets Covered New Earswick Across the village Foxwood Woodlands Heron Avenue; Sherringham Drive; Teal Drive; Wenham Road; Sandmartin Court *Derwenthorpe Across the estate Holgate James Backhouse Place Huntington Albert Close; Carnock Close; Dickens Close; Disraeli Close; Geldof Road; Homestead Close; Nightingale Close; Stephenson Close; Theresa Close; Victoria Way Bootham Pembroke Street; Frederic Street Holgate Park Bonnington Court; Hillary Garth Clementhorpe Vine Street; Board Street Leeman Road area Bismarck Street South Bank area Trafalgar Street; Finsbury Street Other Inside City of York Council Acomb Road; Bridle Way; Birch Park; -

6 Willow Grove, Earswick, York, Yo32 9Sn

6 WILLOW GROVE, EARSWICK, YORK, YO32 9SN A BUILDING PLOT OF APPROXIMATELY 0.31 ACRES WITH PLANNING APPROVAL FOR 2 NO. INDIVIDUAL DETACHED 3 BEDROOMED FAMILY HOMES WITH GARDENS AND GARAGES. GUIDE PRICE £400,000 A building plot of approximately 0.31 acres with Planning Approval for 2 No. AGENTS NOTE individual detached 3 bedroomed family homes with gardens and garages. Full plans and Planning Consents can be inspected at the Williamsons office in Easingwold at Byrne House, Chapel Street, Easingwold, YO61 3AE. Mileages: York - 5 miles, Harrogate - 23 miles, Leeds - 35 miles (distances Approximate) FOR SALE - FREEHOLD An infrequent opportunity to acquire a Building Plot of approximately 0.31 acres, located in a highly convenient semi rural position overlooking farmland at the front and minutes' drive from York outer ring road, Monks Cross, Vangarde Shopping Park and readily accessible to York. York City Council have granted Planning Consent (Application 15/01152/FUL) on the 6th July 2015 for the demolition of the existing bungalow and the erection of 2 No. detached dwellings (subject to a number of conditions), a copy can be inspected at Williamsons Easingwold office. PLANNING AUTHORITY York City Council, West Offices, Station Rise, York, YO1 6GA Tel: 01904 551550 WATER & DRAINAGE Yorkshire Water Authority, P.O. Box 52, Bradford, BD3 7YD. Tel: 0800 1385 383 ELECTRICITY (YEDL) C E Electric Network Connections, Cargo Fleet Lane, Middlesbrough, TS3 8DG. Tel: 08450 702 703. HIGHWAYS North Yorkshire Country Council, Country Hall, Northallerton, DL7 8AD. Tel: 0845 872 7374. TENURE Freehold, with vacant possession upon completion. LOCATION Earswick provides easy access to York City Centre and the outer ring road, which in turn leads to all major road networks. -

Agenda Reports Pack (Public) 01/04/2014, 17.30

Notice of a public meeting of Cabinet To: Councillors Alexander (Chair), Crisp, Cunningham- Cross, Levene, Looker, Merrett, Simpson-Laing (Vice- Chair) and Williams Date: Tuesday, 1 April 2014 Time: 5.30 pm Venue: The George Hudson Board Room - 1st Floor West Offices (F045) A G E N D A Notice to Members - Calling In : Members are reminded that, should they wish to call in any item* on this agenda, notice must be given to Democracy Support Group by 4:00 pm on Thursday 3 April 2014 . *With the exception of matters that have been the subject of a previous call in, require Full Council approval or are urgent which are not subject to the call-in provisions. Any called in items will be considered by the Corporate and Scrutiny Management Committee. 1. Declarations of Interest At this point, Members are asked to declare: • any personal interests not included on the Register of Interests • any prejudicial interests or • any disclosable pecuniary interests which they may have in respect of business on this agenda. 2. Exclusion of Press and Public To consider the exclusion of the press and public from the meeting during consideration of the following: Annexes 1 to 4 to Agenda Item 8 (Formation of a Y.P.O. Limited Company) on the grounds that they contain information relating to the financial or business affairs of any particular person (including the authority holding that information). This information is classed as exempt under paragraph 3 of Schedule 12A to Section 100A of the Local Government Act 1972 (as revised by The Local Government (Access to Information) (Variation) Order 2006). -

Land at Foss Bank Farm, Strensall Road, Earswick, York, Yo32 9Sw

OUTSTANDING RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT SITE LAND AT FOSS BANK FARM, STRENSALL ROAD, EARSWICK, YORK, YO32 9SW Offers are invited for the freehold interest in the above site, subject to contract only PRICE ON APPLICATION Estate Agents Chartered Surveyors Auctioneers Land at Foss Bank Farm, Strensall Road, Earswick, York, YO32 9SW FOREWORD TENURE We are delighted to offer for sale this prime residential development opportunity We understand the tenure to be freehold although we have not inspected the title deeds benefiting from outline planning consent for the erection of four detached dwellings or other documentary evidence. The vacant possession of the site will be available on (one to be retained by the vendor), located off a private access drive and set in a completion. backwater position approximately 150m from Strensall Road on the edge of the ever- popular village of Old Earswick. VIEWINGS Strictly by arrangement with the selling agent. THE SITE The site is shown clearly by the red verge on the plan set out within this brochure. PLANNING By decision number 16/02792/OUT, outline planning consent has been granted for the SERVICES erection of four detached dwellings. The position of the four houses on the site are set Mains services of water, and electricity are understood to be available to the site. out by a previous application, reference 15/0283/FUL. The revised outline application Prospective purchasers should make their own enquiries regarding connections to the allows for the erection of four 1½ storey detached houses of traditional structure. The appropriate statutory authorities. These are believed to be:- successful applicant will be required to submit their own Reserved Matters Application.