What Works to Curb Political Corruption?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protecting Politics: Deterring the Influence Of

Protecting Politics Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Protecting Politics: Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Elections are essential elements of democratic systems. Unfortunately, abuse and manipulation (including voter intimidation, vote buying or ballot stuffing) can distort these processes. However, little attention has been paid to an intrinsic part of this threat: the conditions and opportunities for criminal interference in the electoral process. Most worrying, few scholars have examined the underlying conditions that make elections vulnerable to organized criminal involvement. This report addresses these gaps in knowledge by analysing the vulnerabilities of electoral processes to illicit interference (above all by organized crime). It suggests how national and international authorities might better protect these crucial and coveted elements of the democratic process. Case studies from Georgia, Mali and Mexico illustrate these challenges and provide insights into potential ways to prevent and mitigate the effects of organized crime on elections. International IDEA Clingendael Institute ISBN 978-91-7671-069-2 Strömsborg P.O. Box 93080 SE-103 34 Stockholm 2509 AB The Hague Sweden The Netherlands T +46 8 698 37 00 T +31 70 324 53 84 F +46 8 20 24 22 F +31 70 328 20 02 9 789176 710692 > [email protected] [email protected] www.idea.int www.clingendael.nl ISBN: 978-91-7671-069-2 Protecting Politics Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Protecting Politics Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Series editor: Catalina Uribe Burcher Lead authors: Ivan Briscoe and Diana Goff © 2016 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance © 2016 Netherlands Institute of International Relations (Clingendael Institute) International IDEA Strömsborg SE-103 34 Stockholm Sweden Tel: +46 8 698 37 00, fax: +46 8 20 24 22 Email: [email protected], website: www.idea.int Clingendael Institute P.O. -

Combating Corruption in Latin America: Congressional Considerations

Combating Corruption in Latin America: Congressional Considerations May 21, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45733 SUMMARY R45733 Combating Corruption in Latin America May 21, 2019 Corruption of public officials in Latin America continues to be a prominent political concern. In the past few years, 11 presidents and former presidents in Latin America have been forced from June S. Beittel, office, jailed, or are under investigation for corruption. As in previous years, Transparency Coordinator International’s Corruption Perceptions Index covering 2018 found that the majority of Analyst in Latin American respondents in several Latin American nations believed that corruption was increasing. Several Affairs analysts have suggested that heightened awareness of corruption in Latin America may be due to several possible factors: the growing use of social media to reveal violations and mobilize Peter J. Meyer citizens, greater media and investor scrutiny, or, in some cases, judicial and legislative Specialist in Latin investigations. Moreover, as expectations for good government tend to rise with greater American Affairs affluence, the expanding middle class in Latin America has sought more integrity from its politicians. U.S. congressional interest in addressing corruption comes at a time of this heightened rejection of corruption in public office across several Latin American and Caribbean Clare Ribando Seelke countries. Specialist in Latin American Affairs Whether or not the perception that corruption is increasing is accurate, it is nevertheless fueling civil society efforts to combat corrupt behavior and demand greater accountability. Voter Maureen Taft-Morales discontent and outright indignation has focused on bribery and the economic consequences of Specialist in Latin official corruption, diminished public services, and the link of public corruption to organized American Affairs crime and criminal impunity. -

The Truth About Voter Fraud 7 Clerical Or Typographical Errors 7 Bad “Matching” 8 Jumping to Conclusions 9 Voter Mistakes 11 VI

Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law is a non-partisan public policy and law institute that focuses on fundamental issues of democracy and justice. Our work ranges from voting rights to redistricting reform, from access to the courts to presidential power in the fight against terrorism. A sin- gular institution—part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group—the Brennan Center combines scholarship, legislative and legal advocacy, and communications to win meaningful, measurable change in the public sector. ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER’S VOTING RIGHTS AND ELECTIONS PROJECT The Voting Rights and Elections Project works to expand the franchise, to make it as simple as possible for every eligible American to vote, and to ensure that every vote cast is accurately recorded and counted. The Center’s staff provides top-flight legal and policy assistance on a broad range of election administration issues, including voter registration systems, voting technology, voter identification, statewide voter registration list maintenance, and provisional ballots. © 2007. This paper is covered by the Creative Commons “Attribution-No Derivs-NonCommercial” license (see http://creativecommons.org). It may be reproduced in its entirety as long as the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law is credited, a link to the Center’s web page is provided, and no charge is imposed. The paper may not be reproduced in part or in altered form, or if a fee is charged, without the Center’s permission. -

Disinformation in Democracies: Strengthening Digital Resilience in Latin America

Atlantic Council ADRIENNE ARSHT LATIN AMERICA CENTER Disinformation in Democracies: Strengthening Digital Resilience in Latin America The Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center broadens understanding of regional transformations through high-impact work that shapes the conversation among policymakers, the business community, and civil society. The Center focuses on Latin America’s strategic role in a global context with a priority on pressing political, economic, and social issues that will define the trajectory of the region now and in the years ahead. Select lines of programming include: Venezuela’s crisis; Mexico-US and global ties; China in Latin America; Colombia’s future; a changing Brazil; Central America’s trajectory; combatting disinformation; shifting trade patterns; and leveraging energy resources. Jason Marczak serves as Center Director. The Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab) is at the forefront of open-source reporting and tracking events related to security, democracy, technology, and where each intersect as they occur. A new model of expertise adapted for impact and real-world results, coupled with efforts to build a global community of #DigitalSherlocks and teach public skills to identify and expose attempts to pollute the information space, DFRLab has operationalized the study of disinformation to forge digital resilience as humans are more connected than at any point in history. For more information, please visit www.AtlanticCouncil.org. This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Independence. The authors are solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations. The Atlantic Council and its donors do not determine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s conclusions. -

Twitter and Millennial Participation in Voting During Nigeria's 2015 Presidential Elections

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2021 Twitter and Millennial Participation in Voting During Nigeria's 2015 Presidential Elections Deborah Zoaka Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Public Administration Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Deborah Zoaka has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Lisa Saye, Committee Chairperson, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Raj Singh, Committee Member, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Christopher Jones, University Reviewer, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer and Provost Sue Subocz, Ph.D. Walden University 2021 Abstract Twitter and Millennial Participation in Voting during Nigeria’s 2015 Presidential Elections by Deborah Zoaka MPA Walden University, 2013 B.Sc. Maiduguri University, 1989 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Public Policy and Administration Walden University May, 2021 Abstract This qualitative phenomenological research explored the significance of Twitter in Nigeria’s media ecology within the context of its capabilities to influence the millennial generation to participate in voting during the 2015 presidential election. Millennial participation in voting has been abysmally low since 1999, when democratic governance was restored in Nigeria after 26 years of military rule, constituting a grave threat to democratic consolidation and electoral legitimacy. The study was sited within the theoretical framework of Democratic participant theory and the uses and gratifications theory. -

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Brazil | Freedom House Page 1 of 19 BrazilFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 75 FREE /100 Political Rights 31 Civil Liberties 44 75 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/brazil/freedom-world/2020 3/6/2020 Brazil | Freedom House Page 2 of 19 Brazil is a democracy that holds competitive elections, and the political arena is characterized by vibrant public debate. However, independent journalists and civil society activists risk harassment and violent attack, and the government has struggled to address high rates of violent crime and disproportionate violence against and economic exclusion of minorities. Corruption is endemic at top levels, contributing to widespread disillusionment with traditional political parties. Societal discrimination and violence against LGBT+ people remains a serious problem. Key Developments in 2019 • In June, revelations emerged that Justice Minister Sérgio Moro, when he had served as a judge, colluded with federal prosecutors by offered advice on how to handle the corruption case against former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, who was convicted of those charges in 2017. The Supreme Court later ruled that defendants could only be imprisoned after all appeals to higher courts had been exhausted, paving the way for Lula’s release from detention in November. • The legislature’s approval of a major pension reform in the fall marked a victory for Brazil’s far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, who was inaugurated in January after winning the 2018 election. It also signaled a return to the business of governing, following a period in which the executive and legislative branches were preoccupied with major corruption scandals and an impeachment process. -

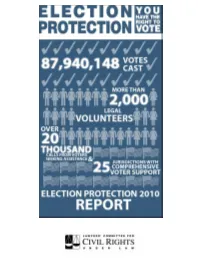

2010 Election Protection Report

2010 Election Protection Report Partners Election Protection would like to thank the state and local partners who led the program in their communities. The success of the program is owed to their experience, relationships and leadership. In addition, we would like to thank our national partners, without whom this effort would not have been possible: ACLU Voting Rights Project Electronic Frontier Foundation National Coalition for Black Civic Participation Advancement Project Electronic Privacy Information Center National Congress of American Indians AFL-CIO Electronic Verification Network National Council for Negro Women AFSCME Fair Elections Legal Network National Council of Jewish Women Alliance for Justice Fair Vote National Council on La Raza Alliance of Retired Americans Generational Alliance National Disability Rights Network American Association for Justice Hip Hop Caucus National Education Association American Association for People with Hispanic National Bar Association Disabilities National Voter Engagement Network Human Rights Campaign American Bar Association Native American Rights Fund IMPACT American Constitution Society New Organizing Institute Just Vote Colorado America's Voice People for the American Way Latino Justice/PRLDEF Asian American Justice Center Leadership Conference on Civil and Project Vote Asian American Legal Defense and Human Rights Rainbow PUSH Educational Fund League of Women Voters Rock the Vote Black Law Student Association League of Young Voters SEIU Black Leadership Forum Long Distance Voter Sierra -

BTI 2018 Country Report — Serbia

BTI 2018 Country Report Serbia This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2018. It covers the period from February 1, 2015 to January 31, 2017. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2018 Country Report — Serbia. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2018 | Serbia 3 Key Indicators Population M 7.1 HDI 0.776 GDP p.c., PPP $ 14512 Pop. growth1 % p.a. -0.5 HDI rank of 188 66 Gini Index 29.1 Life expectancy years 75.5 UN Education Index 0.779 Poverty3 % 1.4 Urban population % 55.7 Gender inequality2 0.185 Aid per capita $ 44.0 Sources (as of October 2017): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2017 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2016. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary Serbia’s current political system is characterized by the dominant rule of one political party at the national and provincial level, as well as most of the local government units. -

Research Conferences on Organised Crime at the Bundeskriminalamt In

Corruption and Organised Crime Threats in Southern Eastern Europe Ugljesa Zvekic Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime 1 Organised Crime and Corruption in the Global Developmental Perspective In this article the emphasis was on a nearly inherent link between organised crime and corruption on a local as well as transnational level. Wherever there is ground prone to corruption, there is also a favourable ground for organised crime; and vice versa. Much of the prone ground for organised corruption is established through firstly a low corruption level which then accelerates to a more sophisticated level of corruption, in particular when linked to organised crime. Furthermore, it was professed that today more intricate activities in or- ganised crime can be linked to more intricate activities in corruption, making them mutually instrumental. Historically speaking, two contradictory trends were identified: Firstly a de- cline in violent crimes over the past century and decades, and secondly an in- crease in global organised crime and corruption, which in turn promoted more international legal responses and cooperation. (Pinker, Mack 2014/ 2015) The phenomenon of organised crime is not new to the global crime trends but the scale and scope have shifted vigorously. Change is also pre- sents in new forms and methods of legitimizing illicitly gained profit. The im- pact comes to light in the form of shifts in major illicit markets, an expansion of new criminal markets as well as a blurring of traditional producer, consu- mer and transit state typologies. Therefore, organised crime and corruption both have broader implications than defined within the traditional security and justice framework; hence they are now recognised as cross-cutting threats to a sustainable development which is also pictured by the 16th goal of the Sustainable Development Goals1. -

Corruption Perceptions Index 2020

CORRUPTION PERCEPTIONS INDEX 2020 Transparency International is a global movement with one vision: a world in which government, business, civil society and the daily lives of people are free of corruption. With more than 100 chapters worldwide and an international secretariat in Berlin, we are leading the fight against corruption to turn this vision into reality. #cpi2020 www.transparency.org/cpi Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. All information was believed to be correct as of January 2021. Nevertheless, Transparency International cannot accept responsibility for the consequences of its use for other purposes or in other contexts. ISBN: 978-3-96076-157-0 2021 Transparency International. Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under CC BY-ND 4.0 DE. Quotation permitted. Please contact Transparency International – [email protected] – regarding derivatives requests. CORRUPTION PERCEPTIONS INDEX 2020 2-3 12-13 20-21 Map and results Americas Sub-Saharan Africa Peru Malawi 4-5 Honduras Zambia Executive summary Recommendations 14-15 22-23 Asia Pacific Western Europe and TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE European Union 6-7 Vanuatu Myanmar Malta Global highlights Poland 8-10 16-17 Eastern Europe & 24 COVID-19 and Central Asia Methodology corruption Serbia Health expenditure Belarus Democratic backsliding 25 Endnotes 11 18-19 Middle East & North Regional highlights Africa Lebanon Morocco TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL 180 COUNTRIES. 180 SCORES. HOW DOES YOUR COUNTRY MEASURE UP? -

A/74/130 General Assembly

United Nations A/74/130 General Assembly Distr.: General 30 July 2019 Original: English Seventy-fourth session Item 109 of the provisional agenda* Countering the use of information and communications technologies for criminal purposes Countering the use of information and communications technologies for criminal purposes Report of the Secretary-General Summary The present report has been prepared pursuant to General Assembly resolution 73/187, entitled “Countering the use of information and communications technologies for criminal purposes”. In that resolution, the General Assembly requested the Secretary-General to seek the views of Member States on the challenges that they faced in countering the use of information and communications technologies for criminal purposes and to present a report based on those views for consideration by the General Assembly at its seventy-fourth session. The report contains information on the views of Member States submitted pursuant to the aforementioned resolution. __________________ * A/74/150. V.19-08182 (E) 190819 200819 *1908182* A/74/130 Contents Page I. Introduction ................................................................... 4 II. Replies received from Governments ............................................... 4 Argentina ..................................................................... 4 Armenia ...................................................................... 6 Australia ..................................................................... 8 Austria ...................................................................... -

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Chapter 204C

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 204C.02 CHAPTER 204C ELECTION DAY ACTIVITIES GENERAL PROVISIONS 204C.23 DEFECTIVE BALLOTS. 204C.01 DEFINITIONS. 204C.24 ELECTION RETURNS; SUMMARY STATEMENTS. 204C.02 CHAPTER APPLICATION; INDIVIDUALS UNABLE 204C.25 DISPOSITION OF BALLOTS. TO WRITE. 204C.26 SUMMARY STATEMENTS AND ENVELOPES FOR 204C.03 PUBLIC MEETINGS PROHIBITED ON ELECTION BALLOT RETURNS; ELECTION OFFICIALS TO DAY. FURNISH. 204C.035 DECEPTIVE PRACTICES IN ELECTIONS. 204C.27 DELIVERY OF RETURNS TO COUNTY AUDITORS. 204C.04 EMPLOYEES; TIME OFF TO VOTE. 204C.28 ELECTION NIGHT; DUTIES OF COUNTY AUDITORS 204C.05 STATE ELECTIONS; HOURS FOR VOTING. AND MUNICIPAL CLERKS. POLLING PLACE ACTIVITIES 204C.29 IMPROPER DELIVERY OF RETURNS. 204C.06 CONDUCT IN AND NEAR POLLING PLACES. CANVASSING BOARDS; CERTIFICATION OF ELECTION RESULTS 204C.07 CHALLENGERS. 204C.31 CANVASSING BOARDS; MEMBERSHIP. 204C.08 OPENING OF POLLING PLACES. 204C.32 CANVASS OF STATE PRIMARIES. 204C.09 BALLOT PREPARATION BY ELECTION JUDGES. 204C.33 CANVASS OF STATE GENERAL ELECTIONS. 204C.10 POLLING PLACE ROSTER; VOTER SIGNATURE CERTIFICATE; VOTER RECEIPT. 204C.34 TIE VOTES. 204C.12 CHALLENGES TO VOTERS; PENALTY. RECOUNTS 204C.13 RECEIVING AND MARKING BALLOTS. 204C.35 FEDERAL, STATE, AND JUDICIAL RACES. 204C.14 UNLAWFUL VOTING; PENALTY. 204C.36 RECOUNTS IN COUNTY, SCHOOL DISTRICT, AND MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS. 204C.15 ASSISTANCE TO VOTERS. 204C.361 RULES FOR RECOUNTS. 204C.16 MISMARKING BALLOTS; DISCLOSURE OF MARKINGS BY