Church Autonomy in the United Kingdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru the National Assembly for Wales

Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru The National Assembly for Wales Y Pwyllgor Materion Cyfansoddiadol a Deddfwriaethol The Constitutional and Legislative Affairs Committee Dydd Llun, 11 Mawrth 2013 Monday, 11 March 2013 Cynnwys Contents Cyflwyniad, Ymddiheuriadau, Dirprwyon a Datganiadau o Fuddiant Introduction, Apologies, Substitutions and Declarations of Interest Offerynnau Nad Ydynt yn Cynnwys Unrhyw Faterion i’w Codi o dan Reolau Sefydlog Rhif 21.2 neu 21.3 Instruments that Raise no Reporting Issues under Standing Order Nos. 21.2 or 21.3 Offerynnau sy’n Cynnwys Materion i Gyflwyno Adroddiad arnynt i’r Cynulliad o dan Reolau Sefydlog Rhif 21.2 neu 21.3 Instruments that Raise Issues to be Reported to the Assembly under Standing Order Nos. 21.2 or 21.3 Cynnig o dan Reol Sefydlog Rhif 17.42 i Benderfynu Gwahardd y Cyhoedd o’r Cyfarfod Motion under Standing Order No. 17.42 to Resolve to Exclude the Public from the Meeting Tystiolaeth Ynghylch yr Ymchwiliad i Ddeddfu a’r Eglwys yng Nghymru Evidence in Relation to the Inquiry on Law Making and the Church in Wales Papurau i’w Nodi Papers to Note Cynnig o dan Reol Sefydlog Rhif 17.42(vi) i Benderfynu Gwahardd y Cyhoedd o’r Cyfarfod 11/03/2013 Motion under Standing Order No. 17.42(vi) to Resolve to Exclude the Public from the Meeting Cofnodir y trafodion yn yr iaith y llefarwyd hwy ynddi yn y pwyllgor. Yn ogystal, cynhwysir trawsgrifiad o’r cyfieithu ar y pryd. The proceedings are reported in the language in which they were spoken in the committee. -

Welsh Church

(S.R. 0-- O. and S.I. Revised to December 31,1948) ---------~ ~--"------- WELSH CHURCH 1. Charter of Incorporation. 2. Burial Grounds (Commencemen~ 1 of Enactment). p. 220. 1. Charter of Incorporation ORDER IN COUNCIl, APPROVING DRAFT CHARTER UNDER SECTION 13 (2) OF THE WELSH CHURCH ACT, 1914 (4 & 5 GEO. 5. c. 91) INCORPORATING THE REPRESENTA TIVE BODY OF THE CHURCH IN WALES. 1919 No. 564 At the Court at Buckingham Palace, the 15th day of April, 1919. PRESENT, The King's Most Excellent Majesty in Gouncil. :\Vhereas there was this day read at the Board a Report of a Cmnmittee of the Lord.. of His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy C.ouncil, dated the 9th day of April, 1919, in the words following, VIZ.:- " Your Majesty having been pleased, by Your Order of the 10th day of February, 1919, to refer unto this Committee the humble Petition of The Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of St. Asaph, The Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of St. David's, 'rhe Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of Bangor, The Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of Llandaff, The Right Honourable Sir John Eldon Bankes, The Right Honourable Sir J ames Richard Atkin, Sir Owen Philipps, G.C.M.G., M.P., and The Honourable Sir John Sankey, G.B.E., praying that Your Majesty would be pleased, in exercise of Your Royal Preroga- 1,ive and of the power in that behalf contained in Section 13 (2) of the Welsh Church Act, 1914, to grant a Charter of Incorpora tion to the persons mentioned in the Second Schedule to the said Petition, and their successors, being the Representative Body of the Church in Wales under the provisions of the said Ad: "1'he Lords of the Committee, in obedience to Your Majesty's said Order of Reference, have taken the said Petition into consideration, and do this day agree humbly to report, as their opinion, to Your Majesty, that a Charter may be grant~~ by Your Majesty in terms of the Draft hereunto annexed. -

Welsh Disestablishment: 'A Blessing in Disguise'

Welsh disestablishment: ‘A blessing in disguise’. David W. Jones The history of the protracted campaign to achieve Welsh disestablishment was to be characterised by a litany of broken pledges and frustrated attempts. It was also an exemplar of the ‘democratic deficit’ which has haunted Welsh politics. As Sir Henry Lewis1 declared in 1914: ‘The demand for disestablishment is a symptom of the times. It is the democracy that asks for it, not the Nonconformists. The demand is national, not denominational’.2 The Welsh Church Act in 1914 represented the outcome of the final, desperate scramble to cross the legislative line, oozing political compromise and equivocation in its wake. Even then, it would not have taken place without the fortuitous occurrence of constitutional change created by the Parliament Act 1911. This removed the obstacle of veto by the House of Lords, but still allowed for statutory delay. Lord Rosebery, the prime minister, had warned a Liberal meeting in Cardiff in 1895 that the Welsh demand for disestablishment faced a harsh democratic reality, in that: ‘it is hard for the representatives of the other 37 millions of population which are comprised in the United Kingdom to give first and the foremost place to a measure which affects only a million and a half’.3 But in case his audience were insufficiently disheartened by his homily, he added that there was: ‘another and more permanent barrier which opposes itself to your wishes in respect to Welsh Disestablishment’, being the intransigence of the House of Lords.4 The legislative delay which the Lords could invoke meant that the Welsh Church Bill was introduced to parliament on 23 April 1912, but it was not to be enacted until 18 September 1914. -

The Cabinet Manual

The Cabinet Manual A guide to laws, conventions and rules on the operation of government 1st edition October 2011 The Cabinet Manual A guide to laws, conventions and rules on the operation of government 1st edition October 2011 Foreword by the Prime Minister On entering government I set out, Cabinet has endorsed the Cabinet Manual as an authoritative guide for ministers and officials, with the Deputy Prime Minister, our and I expect everyone working in government to shared desire for a political system be mindful of the guidance it contains. that is looked at with admiration This country has a rich constitution developed around the world and is more through history and practice, and the Cabinet transparent and accountable. Manual is invaluable in recording this and in ensuring that the workings of government are The Cabinet Manual sets out the internal rules far more open and accountable. and procedures under which the Government operates. For the first time the conventions determining how the Government operates are transparently set out in one place. Codifying and publishing these sheds welcome light on how the Government interacts with the other parts of our democratic system. We are currently in the first coalition Government David Cameron for over 60 years. The manual sets out the laws, Prime Minister conventions and rules that do not change from one administration to the next but also how the current coalition Government operates and recent changes to legislation such as the establishment of fixed-term Parliaments. The content of the Cabinet Manual is not party political – it is a record of fact, and I welcome the role that the previous government, select committees and constitutional experts have played in developing it in draft to final publication. -

The Pre-Action Protocol for Judicial Review Under the Civil Procedure Rules

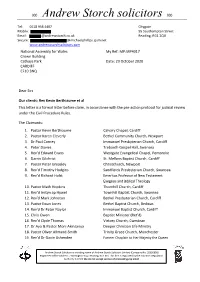

000 Andrew Storch solicitors 000 Tel: 0118 958 4407 Citygate Mobile: 95 Southampton Street Email: @andrewstorch.co.uk Reading, RG1 2QU Secure: @michaelphillips.cjsm.net www.andrewstorchsolicitors.com National Assembly for Wales My Ref: MP:MP4017 Crown Building Cathays Park Date: 23 October 2020 CARDIFF CF10 3NQ Dear Sirs Our clients: Rev Kevin Berthiaume et al This letter is a formal letter before claim, in accordance with the pre-action protocol for judicial review under the Civil Procedure Rules. The Claimants: 1. Pastor Kevin Berthiaume Calvary Chapel, Cardiff 2. Pastor Karen Cleverly Bethel Community Church, Newport 3. Dr Paul Corney Immanuel Presbyterian Church, Cardiff 4. Peter Davies Treboeth Gospel Hall, Swansea 5. Rev’d Edward Evans Westgate Evangelical Chapel, Pembroke 6. Darrin Gilchrist St. Mellons Baptist Church, Cardiff 7. Pastor Peter Greasley Christchurch, Newport 8. Rev’d Timothy Hodgins Sandfields Presbyterian Church, Swansea 9. Rev’d Richard Holst Emeritus Professor of New Testament Exegesis and Biblical Theology 10. Pastor Math Hopkins Thornhill Church, Cardiff 11. Rev’d Iestyn ap Hywel Townhill Baptist Church, Swansea 12. Rev'd Mark Johnston Bethel Presbyterian Church, Cardiff 13. Pastor Ewan Jones Bethel Baptist Church, Bedwas 14. Rev'd Dr Peter Naylor Immanuel Baptist Church, Cardiff 15. Chris Owen Baptist Minister (Ret’d) 16. Rev’d Clyde Thomas Victory Church, Cwmbran 17. Dr Ayo & Pastor Moni Akinsanya Deeper Christian Life Minstry 18. Pastor Oliver Allmand-Smith Trinity Grace Church, Manchester 19. Rev’d Dr Gavin Ashenden Former Chaplain to Her Majesty the Queen Andrew Storch Solicitors is a trading name of Andrew Storch Solicitors Limited (Company No. -

Church and State in the Twenty-First Century

THIRTY-SECOND ANNUAL CONFERENCE 5 to 7 April 2019 Cumberland Lodge, Windsor Great Park Church and State in the Twenty-first Century Slide 7 Table of contents Welcome and Introduction 3 Conference programme 4-6 Speakers' biographies 7-10 Abstracts 11-14 Past and future Conferences 15 Attendance list 16-18 AGM Agenda 19-20 AGM Minutes of previous meeting 21-23 AGM Chairman’s Report 24-27 AGM Accounts 2017/18 28-30 Committee membership 31 Upcoming events 32 Day Conference 2020 33 Cumberland Lodge 34-36 Plans of Cumberland Lodge 37-39 Directions for the Royal Chapel of All Saints 40 2 Welcome and Introduction We are very pleased to welcome you to our Residential Conference at Cumberland Lodge. Some details about Cumberland Lodge appear at the end of this booklet. The Conference is promoting a public discussion of the nature of establishment and the challenges it may face in the years ahead, both from a constitutional vantage point and in parochial ministry for the national church. A stellar collection of experts has been brought together for a unique conference which will seek to re-imagine the national church and public religion in the increasingly secular world in the current second Elizabethan age and hereafter. Robert Blackburn will deliver a keynote lecture on constitutional issues of monarchy, parliament and the Church of England. Norman Doe and Colin Podmore will assess the centenaries of, respectively, the Welsh Church Act 1914 and the Church of England Assembly (Powers) Act 1919 (known as the ‘Enabling Act’), and the experience of English and Welsh Anglicanism over this period. -

Section 2 of the Parliament Act 1911

SECTION 2 OF THE PARLIAMENT ACT 1911 This pamphlet is intended for members of the Office of the Parliamentary Counsel. References to Commons Standing Orders are to the Standing Orders of the House of Commons relating to Public Business of 1 May 2018 and the addenda up to 6 February 2019. References to Lords Standing Orders are to the Standing Orders of the House of Lords relating to Public Business of 18 May 2016. References to Erskine May are to Erskine May on Parliamentary Practice (25th edition, 2019). Office of the Parliamentary Counsel 11 July 2019 CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION General . 1 Text of section 2. 1 Uses of section 2 . 2 Role of First Parliamentary Counsel . 3 CHAPTER 2 APPLICATION OF SECTION 2 OF THE PARLIAMENT ACT 1911 Key requirements . 4 Bills to which section 2(1) applies . 4 Sending up to Lords in first Session . 6 Rejection by Lords in first Session . 7 Same Bill in second Session. 7 Passing Commons in second Session . 10 Sending up to Lords in second Session . 11 Rejection by Lords in second Session . 11 Commons directions . 14 Royal Assent . 14 CHAPTER 3 SUGGESTED AMENDMENTS Commons timing and procedure . 16 Function of the procedure . 17 Form of suggested amendment . 19 Lords duty to consider. 19 Procedure in Lords . 19 CHAPTER 4 OTHER PROCEDURAL ISSUES IN THE SECOND SESSION Procedure motions in Commons . 21 Money Resolutions . 23 Queen’s and Prince’s Consent . 23 To and Fro (or “ping-pong”) . 23 APPENDIX Jackson case: implied restrictions under section 2(1) . 25 —i— CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION General 1.1 The Parliament Acts 1911 and 1949 were passed to restrict the power of veto of the House of Lords over legislation.1 1.2 Section 1 of the 1911 Act is about securing Royal Assent to Money Bills to which the Lords have not consented. -

1 LAW MAKING and the CHURCH in WALES Norman Doe Like Other

LAW MAKING AND THE CHURCH IN WALES Norman Doe Like other religious organisations, the Church in Wales is regulated by two broad categories of law: the (external) law of the State and the (internal) law of the church. This short paper sets out the fundamentals of the position of the Church in Wales under State law and its consequences for law-making for the church by the State and its institutions (e.g. Parliament, Courts, National Assembly for Wales and Welsh Government) and for law-making within the church (by e.g. its Governing Body). 1. The Welsh Church Act 1914: Disestablishment and Ecclesiastical Law The foundation of the Church in Wales resulted from the disestablishment of the Church of England in Wales under the Welsh Church Act 1914. The ecclesiastical law of England and Wales ceased to apply to the Church in Wales as the law of the land, but some elements of it continue to apply as such (e.g. marriage and burial). The foundation of the institutional Church in Wales under State law followed the disestablishment of the Church of England in Wales by Parliament in 1920 through the Welsh Church Act 1914. Until 1920 „the Church of England and the Church in Wales were one body established by law‟.1 On the day of disestablishment (31 March 1920), the Church of England, in Wales and Monmouthshire, ceased to be „established by law‟ (s. 1): no person was to be appointed by the monarch to any ecclesiastical office in the Church in Wales; every ecclesiastical corporation was dissolved; Welsh bishops ceased to sit in the House of Lords; and bishops and clergy were no longer disqualified from election to the House of Commons (ss.1, 2, 3).2 The 1914 Act also provides that, as from the date of disestablishment, „the ecclesiastical law of the Church in Wales shall cease to exist as law‟ for the Welsh church (s. -

Devolution in the UK: Historical Perspective Dr

Devolution in the UK: Historical Perspective Dr. Andrew Blick, King’s College London This paper considers the current territorial distribution of political authority within the United Kingdom (UK), and prospects for the future, from an historical perspective. It discusses the uneven and diverse ways in which UK governance has developed, how they have led to the present position, and what the consequent trajectories of development might be. The author also considers whether the analysis of specific circumstances or tendencies from the past may enhance our understanding of contemporary issues. The overall purpose of the paper is to answer the questions: how did we get where we are now, and what guidance might past patterns of development offer for the future? It begins by considering the nature of the UK as a multinational, ‘union’ state, and the constitutional implications. Next it discusses the history of devolution, both as a concept and a practical reality, the different models employed, and the particular issues that arise. Finally, it assesses what might be the range of options of the future development of devolution in the UK, based on the patterns to date. A multinational union The UK came into being (and then lost some of its territory) in a series of bilateral actions. England fully absorbed Wales in the mid-sixteenth century. Scotland and England entered into a union, forming the United Kingdom of Great Britain, in 1706- 1707. The Act of Union between Great Britain and Ireland was passed in 1800, creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The departure of most of Ireland in the 1920s led eventually to the adoption of a new name for the country, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. -

Download Conference Booklet

THIRTY-SECOND ANNUAL CONFERENCE 5 to 7 April 2019 Cumberland Lodge, Windsor Great ParK Church and State in the Twenty-first Century Slide 7 Table of contents Welcome and Introduction 3 Conference programme 4-6 Speakers' biographies 7-10 Abstracts 11-14 Past and future Conferences 15 Attendance list 16-18 AGM Agenda 19-20 AGM Minutes of previous meeting 21-23 AGM Chairman’s Report 24-27 AGM Accounts 2017/18 28-30 Committee membership 31 Upcoming events 32 Day Conference 2020 33 Cumberland Lodge 34-36 Plans of Cumberland Lodge 37-39 Directions for the Royal Chapel of All Saints 40 2 Welcome anD IntroDuction We are very pleased to welcome you to our Residential Conference at Cumberland Lodge. Some details about Cumberland Lodge appear at the end of this booklet. The Conference is promoting a public discussion of the nature of establishment and the challenges it may face in the years ahead, both from a constitutional vantage point and in parochial ministry for the national church. A stellar collection of experts has been brought together for a unique conference which will seek to re-imagine the national church and public religion in the increasingly secular world in the current second Elizabethan age and hereafter. Robert Blackburn will deliver a keynote lecture on constitutional issues of monarchy, parliament and the Church of England. Norman Doe and Colin Podmore will assess the centenaries of, respectively, the Welsh Church Act 1914 and the Church of England Assembly (Powers) Act 1919 (known as the ‘Enabling Act’), and the experience of English and Welsh Anglicanism over this period. -

Use of Theses

Australian National University THESES SIS/LIBRARY TELEPHONE: +61 2 6125 4631 R.G. MENZIES LIBRARY BUILDING NO:2 FACSIMILE: +61 2 6125 4063 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY EMAIL: [email protected] CANBERRA ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA USE OF THESES This copy is supplied for purposes of private study and research only. Passages from the thesis may not be copied or closely paraphrased without the written consent of the author. THE AUSTRALIAN CHURCHES IN THE GREAT WAR ATTITUDES AND ACTIVITIES OF THE MAJOR CHURCHES by Michael McKernan A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Australian National University February 1975 This thesis is my own work Michael McKernan Ill CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v ABBREVIATIONS vi A NOTE ON TERMS vii INTRODUCTION ix CHAPTER 1 Churches in 1914 1 CHAPTER 2 August 1914 31 CHAPTER 3 Chaplains and the A.I .P. 54 CHAPTER 4 'These Glorious Days' January-June 1915 84 CHAPTER 5 The Failure of Recruiting 106 CHAPTER 6 Priorities 129 CHAPTER 7 The Conscription Years 155 CHAPTER 8 The Chaplain the Soldier and Religion 184 CHAPTER 9 Pacifists 208 CHAPTER 10 Peace 229 CHAPTER 11 Epilogue and Conclusion 253 APPENDICES 267 BIBLIOGRAPHY 309 ABSTRACT Australian churchmen accepted war when it came in August 1914 and sought to explain it to the Australian people. Their explanation relied on the belief that God could only permit what was ultimately good. They expected the war to convince the people that faith in material progress was inadequate and hoped that they would turn to faith in God. -

1. Craig Prescott

Title Page ENHANCING THE METHODOLOGY OF FORMAL CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE IN THE UK A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2014 CRAIG PRESCOTT SCHOOL OF LAW Contents Title Page 1 Contents 2 Table of Abbreviations 5 Abstract 6 Declaration 7 Copyright Statement 8 Acknowledgements 9 Introduction 10 1. ‘Constitutional Unsettlement’ 11 2. Focus on Procedures 18 3. Outline of the Thesis 24 Chapter 1 - Definitions 26 1. ‘Constitutional’ 26 2. ‘Change’ 34 3. ‘Constitutional Change’ 36 4. Summary 43 Chapter 2 - The Limits of Formal Constitutional Change: Pulling Iraq Up By Its Bootstraps 44 1. What Are Constitutional Conventions? 45 Page "2 2. Commons Approval of Military Action 48 3. Conclusion 59 Chapter 3 - The Whitehall Machinery 61 1. Introduction 61 2. Before 1997 and New Labour 66 3. Department for Constitutional Affairs 73 4. The Coalition and the Cabinet Office 77 5. Where Next? 82 6. Conclusion 92 Chapter 4 - The Politics of Constitutional Change 93 1. Cross-Party Co-operation 93 2. Coalition Negotiations 95 3. Presentation of Policy by the Coalition 104 4. Lack of Consistent Process 109 Chapter 5 - Parliament 114 1. Legislative and Regulatory Reform Act 2006 119 2. Constitutional Reform Act 2005 133 3. Combining Expertise With Scrutiny 143 4. Conclusion 156 Chapter 6 - The Use of Referendums in the Page "3 UK 161 1. The Benefits of Referendums 163 2. Referendums and Constitutional Change 167 3. Referendums In Practice 174 4. Mandatory Referendums? 197 5. Conclusion 205 Chapter 7 - The Referendum Process 208 1.