MESMP03465 Iacobelli G.Pdf (2.521Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Mr. Ford Risks Alienating His Key Supporters: Both the Business Community and Fellow Conservatives

Queen’s Park Today – Daily Report November 2, 2020 Quotation of the day “Mr. Ford risks alienating his key supporters: both the business community and fellow conservatives. And Mr. Kenney, experts warn, could quickly set off a public-health disaster if the situation gets out of control.” The Globe and Mail compares Ontario and Alberta's pandemic responses. While Premier Jason Kenney has been criticized for a lighter-touch approach, Premier Doug Ford may be pivoting to Kenney's playbook, asking health officials to draft a plan to ease restrictions in hot spots. Today at Queen’s Park Written by Sabrina Nanji On the schedule The house reconvenes at 9 a.m. for private members’ business; on this morning's docket is second reading of NDP MPP Jeff Burch's Bill 164, Protecting Vulnerable Persons in Supportive Living Accommodation Act. Burch's bill would establish a licensing system for operators of supportive living settings such as nursing homes and children's residences. Bill 202, Soldiers' Aid Commission Act — which shakes up the commission's operations and reporting requirements — was referred back to the house from committee last week and is expected to be called for third reading this afternoon. With a handful of government bills currently at the committee stage, Bill 213 and Bill 207 are the only other ones that could be up for debate today. Bill 213, at second reading, is the red-tape reduction legislation that also gives degree-granting powers and university status to Charles McVety's Canada Christian College. Bill 207 is now back from committee study and poised for third reading; it would align provincial family law with recent federal changes. -

News Release May 25, 2020 Councillors Welcome New Bike

News Release May 25, 2020 Councillors welcome new bike lanes along Bloor and University as part of City’s COVID-19 Response Toronto City Councillors Joe Cressy (Spadina-Fort York), Mike Layton (University-Rosedale), and Kristyn Wong-Tam (Toronto Centre) welcomed tHe announcement of new separated bike lanes tHis morning along Bloor Street and University Avenue, as part of tHe City’s ActiveTO program. THese bike lanes will make it easier for residents and front-line workers to cycle to work and practice pHysical distancing. As we begin to transition to recovery in Toronto and more businesses and workplaces open back up, How we will get around is a pressing challenge. For safe pHysical distancing we need to create alternative and safe metHods of transportation. Switching to driving isn’t an option for many, and even if it was, tHe resulting gridlock will grind traffic to a Halt, strangling our city and economy. It’s time for a new approach. Bike lanes on University Avenue (tHrougH Queen’s Park Crescent) and on Bloor Street will provide relief to two subway lines, creating more space on tHe subway for tHose wHo need to ride transit, and offering a new cycling option tHat is safe and uses our limited road space as efficiently as possible to move tHe most people. THe new separated bike lanes on tHese routes will connect cyclists to many of tHe area’s Hospitals and HealtH care facilities. Doctors for Safe Cycling, representing many pHysicians from downtown Hospitals, issued a letter earlier tHis montH asking for protected bike lanes, so tHat HealtH care workers, clients, and otHers can commute safely to tHe Hospital district by bike. -

March 29, 2018 Mayor John Tory Office of the Mayor City Hall, 2Nd Floor 100 Queen St. W. Toronto, on M5H 2N2 Realizing Toronto Y

March 29, 2018 Mayor John Tory Office of the Mayor City Hall, 2nd Floor 100 Queen St. W. Toronto, ON M5H 2N2 Realizing Toronto’s Opportunity to Redevelop Downsview Your Worship, On behalf of the Ontario Society of Professional Engineers (OSPE), I am writing to request your support for the redevelopment of the Downsview lands: an incredible, multi-billion dollar opportunity for the city of Toronto to increase its supply of housing, attract investment and jobs and cement itself as a global centre for engineering innovation. As you are aware, Bombardier Aerospace announced their intention to relocate their operations at Downsview. For Toronto, this move presents a tremendous prospect for innovation and urban renewal that is unparalleled in modern history. Spanning an impressive 375-acres of prime development lands, Toronto’s opportunity at Downsview supersedes previous urban development success stories such as New York’s Hudson Yards and London’s Canary Wharf (24 and 97-acres respectively). Not only is its sheer size unprecedented—Downsview is also shovel-ready, presenting Toronto with a turn-key public project that complements existing infrastructure. Unlike most urban renewal projects around the globe, this development is able to monopolize on existing public infrastructure stock, thereby avoiding the time and resource costs typically associated with the construction of new service and transit linkages. The Downsview lands are situated at the epicentre of three world-class universities and benefits from exceptional connections to existing subway, rail, and highway transportation infrastructure. Developing Downsview can improve the flow and functionality of Toronto’s transit network. The development of the Downsview lands promises to improve ridership and the efficiency of the entire transit network by encouraging two-way passenger flows. -

Steven Martin Robert White Ext.5240 Jeff Irons Ext.5272 Bill Acorn Ext

(September 11, 2018 / 14:43:43) 109324-1 IBEW353-SeptNL_p01.pdf .1 News & Views 09/29/21 NEWSLETTER • SEPTEMBER 2018 By: Steven Martin, Business Manager / Financial Secretary 09/29/21 ith Labour Day fast approaching we find ourselves Cesar Palacio and Anthony Perruzza. It is unfortunate that this BUSINESS MANAGER/ dealing with the lockout of the International same motion was defeated a few weeks earlier. 09/29/21 09/29/21 FINANCIAL SECRETARY Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), W This Labour Day we will be starting the march as normal, Steven Martin Local 58. Local 58 represent the stage hands at Exhibition however, we will not be heading into the exhibition but Place. The Board of Governors (BOG) have locked them out PRESIDENT instead we will be marching to Lamport Stadium. We have since July 20th. IATSE has been working at the CNE for over Robert White Ext.5240 already been told that if we do not go into the Ex we will not 100 years,09/29/21 covering BMO Field, Queen Elizabeth Theatre, be given wristbands for our members. It is truly unfortunate VICE-PRESIDENT Coca Cola Coliseum and the Enercare Centre. It seems as 09/29/21 09/29/21 that city council 09/29/21 would put corporate greed over the worker’s Jeff Irons Ext.5272 though the BOG are focused on removing IATSE’s union rights and they should be held accountable for it. The best security clauses from their collective agreement to allow more RECORDING SECRETARY way for that to happen is on October 22 when we have our contracting out of work. -

Funding Arts and Culture Top-10 Law Firms

TORONTO EDITION FRIDAY, DECEMBER 16, 2016 Vol. 20 • No. 49 2017 budget overview 19th annual Toronto rankings FUNDING ARTS TOP-10 AND CULTURE DEVELOPMENT By Leah Wong LAW FIRMS To meet its 2017 target of $25 per capita spending in arts and culture council will need to, not only waive its 2.6 per cent reduction target, but approve an increase of $2.2-million in the It was another busy year at the OMB for Toronto-based 2017 economic development and culture budget. appeals. With few developable sites left in the city’s growth Economic development and culture manager Michael areas, developers are pushing forward with more challenging Williams has requested a $61.717-million net operating proposals such as the intensifi cation of existing apartment budget for 2017, a 3.8 per cent increase over last year. neighbourhoods, the redevelopment of rental apartments with Th e division’s operating budget allocates funding to its implications for tenant relocation, and the redevelopment of four service centres—art services (60 per cent), museum and existing towers such as the Grand Hotel, to name just a few. heritage services (18 per cent), business services (14 per cent) While only a few years ago a 60-storey tower proposal and entertainment industries services (8 per cent). may have seemed stratospheric, the era of the supertall tower One of the division’s major initiatives for 2017 is the city’s has undeniably arrived. In last year’s Toronto law review, the Canada 150 celebrations. At the end of 2017 with the Canada 82- and 92-storey Mirvish + Gehry towers were the tallest 150 initiatives completed, $4.284-million in one-time funding buildings brought before the board. -

December 23, 2020 SENT VIA EMAIL: Mayor [email protected]

December 23, 2020 SENT VIA EMAIL: [email protected] Dear Mayor John Tory, Prior to the COVID-19 crisis, the afforDable housinG crisis in Toronto was untenable. With the panDemic, the lack of afforDable housinG anD inaDequacy of the shelter system in Toronto has been GlarinG. Folks without access to safe, stable, anD afforDable housinG have not founD safety anD comfort in a shelter. Encampments proviDe this safety anD comfort anD proviDe people with aGency to choose how anD where they want to live. Encampments allow people to live in the neiGhbourhooDs of their choice where they have community, family, easy access to their places of work anD access services that are meaninGful to them. Encampments allow this access free of the fear of contractinG COVID-19 that arises in communal shelter livinG situations. The City of Toronto’s winter plan for unhouseD people Does not aDequately aDDress the neeDs of the many people livinG in encampments. The plan unDerestimates how many people are livinG on the streets (it estimates 500 people, while aDvocates anD outreach workers estimate over 1000), anD offers conGreGate caGe-like settinGs like The Better LivinG Centre as an option DurinG a Global panDemic. Forcibly relocatinG people from their homes DurinG a panDemic is a serious public health concern anD an affront to their DiGnity. The forceD clearinG of encampments is not a solution. We know the risk to health anD life that homelessness creates, anD we Know that beinG homeless is not a crime but is a manifestation of faileD systems. The City of Toronto shoulD be usinG its resources to support makinG encampments safer anD to fix this system by finDinG permanent afforDable housinG solutions that allow people to remain in the communities where encampments are locateD insteaD of usinG its resources to criminalize those people livinG in encampment. -

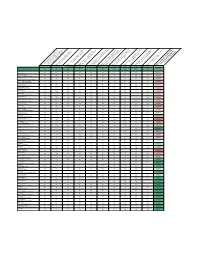

Voting Records on Transit

2017 Toronto's Hands Yonge subway extension (subway station accessibility). Sheppard subway extension. votes not calculated) dedicated to transit service and build the Scarborough subway $2 million to relieve overcrowding Personal Vehicle Tax, with revenues friendly decisions (absent expansion, and compliance with AODA Program for low-income Torontoniansbudgets when you factor in inflation. EX3.4 (M3a) - Do not report on reinstatingEX16.1 (M1) - Proceed with theEX16.1 plan to (M9) - Request report consideringEX16.37routes (M2b) as part- consider of 2017 cutting budgetEX 20.10TTC direction (M2) - Do not establishEX25.18 Fair2017 -Pass Votelevels to for freeze 2018, all effectively budgetsEX22.2 andat cutting(M2) traction - Don't power fund TTCreliability signalEX25.1 initiatives track (M6b) in- Prioiritize ReliefEX31.2 Line (M3)over - Increase the TTCMM41.36 budget by - Keeping Toronto'sVotes Transit in favour in of transit rider- LINK: http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2015.EX3.4LINK: http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2016.EX16.1LINK: http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2016.EX16.37LINK: http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2016.EX20.10LINK: http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2017.EX25.18 LINK: http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2017.EX22.2LINK: http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2017.EX25.1LINK: http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2018.EX31.2LINK: http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2018.MM41.36 -

“You're Welcome.”

Queen’s Park Today – Daily Report May 15, 2019 Quotation of the day “You’re welcome.” Former premier Kathleen Wynne’s message to Environment Minister Rod Phillips after he boasted Ontario’s progress on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, most of which occurred under her previous government. Today at Queen’s Park On the schedule The House convenes at 9 a.m. The government could call any of the following pieces of business in the morning and afternoon: ● The government’s time-allocation motion on Bill 107; ● Bill 107, Getting Ontario Moving Act; ● Bill 108, More Homes, More Choice Act; and ● Bill 100, Protecting What Matters Most Act (the budget measures act). Tuesday’s debates and proceedings In the morning MPPs debated the time-allocation motion for Bill 107; in the afternoon Bill 108 was debated at second reading. In the park A rally in protest of the government’s changes to social assistance will take place around noon. The Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Association of Ontario is scheduled to hold its lobby day and an evening reception. Toronto city manager warns of a ‘second tax bill’ for homeowners due to Ford government cuts Death of services and more taxes — those are the options weighing on Toronto City Hall as it grapples with a nearly $180-million budget hole created by funding cuts made by the Ford government. On Tuesday, city council passed Toronto Mayor John Tory’s motion formally calling on the province to reverse the cuts, and directing City Manager Chris Murray to report on potential “service cuts and tax changes that may be required” to fill gaps in the already-approved 2019 budget. -

The Race Is on Industry Positive

TORONTO EDITION FRIDAY, APRIL 4, 2014 Vol. 18 • No. 14 Trinity-Spadina federal by-election Development Permit System THE RACE INDUSTRY IS ON POSITIVE By Sarah Ratchford By Edward LaRusic With Olivia Chow’s former federal seat vacant, the race to As Toronto’s consultation process ends, the development replace her in Trinity-Spadina has begun. While there is no industry remains cautiously optimistic about the proposed word yet when the by-election will be held, both the Liberals offi cial plan amendment to allow a development permit and NDP are gearing up to win the riding where aff ordable system as an alternative to traditional zoning. housing and public transit are pressing priorities, according to If implemented, a development permit system would allow the local councillors. the city to create development permit “by-laws” that would First out of the gate is Stephen Lewis Foundation senior replace the current zoning with a process that eff ectively advisor Joe Cressy, who has announced his intention to seek combines zoning compliance, minor variances and site plan the NDP nomination at the party’s April 10th meeting. Cressy’s approval. Consultation and studies would be done upfront, goal is to pick up where Olivia Chow left off . creating a fully built-out vision for a defi ned area. “[Chow] had a reputation, and built a legacy, as somebody BILD policy and government relations vice president Paula who stood up every single day as a tireless representative for Tenuta said they are “extremely supportive” of implementing the people of Trinity-Spadina,” Cressy tells NRU. -

Agenda Item Historyана2015.PG6.7

7/12/2016 Agenda Item History 2015.PG6.7 app.toronto.ca Agenda Item History 2015.PG6.7 PG6.7 ACTION Amended Ward:All Sections 37 and 45(9), Community Benefits Secured in 2013 and 2014 City Council Decision City Council on September 30, October 1 and 2, 2015, adopted the following: 1. City Council request the Chief Planner and Executive Director, City Planning to report annually on the Section 37 and 45 benefits secured in the preceding year. 2. City Council direct Planning staff to post Section 37 and Section 45 monies outlined in the report (August 31, 2015) from the Chief Planner and Executive Director, City Planning on the City of Toronto Planning Division's website and City Council direct Planning staff to make this information available in a format compatible with the City of Toronto's Open Data catalogue. 3. City Council request the Chief Planner and Executive Director, City Planning to review Section 37 obligations as they pertain to development under 10,000 square metres and to report on policy alternatives to Council through the Planning and Growth Management Committee. Background Information (Committee) (August 31, 2015) Report and Attachments 1 and 2 from the Chief Planner and Executive Director, City Planning on Sections 37 and 45(9), Community Benefits Secured in 2013 and 2014 (http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2015/pg/bgrd/backgroundfile83196.pdf ) Motions (City Council) 1 Motion to Amend Item (Additional) moved by Councillor Paul Ainslie (Carried) That: 1. City Council direct Planning staff to post Section 37 and Section 45 monies outlined in the report (August 31, 2015) from the Chief Planner and Executive Director, City Planning on the City of Toronto Planning Division's website and City Council direct Planning staff to make this information available in a format compatible with the City of Toronto's Open Data catalogue. -

Toronto Endorsees2018- Tabloid

Labour Council Endorsed Toronto Candidates 2018 Toronto Disrict School Board Toronto Jennifer Keesmaat Amber Morley Gord Perks Lekan Olawoye Maria Augimeri Ali Mohamed-Ali Shawn Rizvi Matias de Dovitiis Robin Pilkey Stephanie Donaldson Mayor Ward 2 Etobicoke Lakeshore Ward 4 Parkdale High Park Ward 5 York South Weston Ward 6 York Centre Ward 1 Etobicoke North Ward 2 Etobicoke Centre Ward 4 Humber River Black Creek Ward 7 Parkdale High Park Ward 9 Davenport Spadina jenniferkeesmaat.com morewithmorley.com votegordperks.ca lekan.ca mariaaugimeri.ca electmohamedali.ca voterizvi.ca matiasdedovitiis.ca robinpilkey.com Fort York stephaniedonaldson.ca Anthony Perruzza Ana Bailão Joe Cressy Mike Layton Joe Mihevc Chris Moise Amara Possian Siham Rayale Jennifer Story Phil Pothen Ward 7 Humber River Black Creek Ward 9 Davenport Ward 10 Spadina Fort York Ward 11 University Rosedale Ward 12 St. Paul’s Ward 10 Toronto Centre Ward 11 Don Valley West Ward 13 Don Valley North Ward 15 Danforth Ward 16 Beaches East York voteanthonyperruzza.com votebailao.ca joecressy.ca mikelayton.ca joemihevc.ca University Rosedale voteamara.ca votesiham.ca jenniferstory.ca philpothen.ca chrismoise.ca Toronto City Council Toronto Kristyn Wong-Tam Paula Fletcher Shelley Carroll Saman Tabasinejad Matthew Kellway David Smith Parthi Kandavel Samiya Abdi Manna Wong Yalini Rajakulasingam Ward 13 Toronto Centre Ward 14 Toronto Danforth Ward 17 Don Valley North Ward 18 Willowdale Ward 19 Beaches East York Ward 17 Scarborough Centre Ward 18 Scarborough Southwest Ward 19 Scarborough -

Advancing the Planning and Design for the Yonge North Subway Extension

Clause 7 in Report No. 11 of Committee of the Whole was adopted, without amendment, by the Council of The Regional Municipality of York at its meeting held on June 29, 2017. Advancing the Planning and Design for the Yonge Subway Extension Committee of the Whole recommends adoption of the following recommendation contained in the report dated June 9, 2017 from the Chief Administrative Officer: 1. Council authorize the negotiation and execution of a Memorandum of Understanding defining governance arrangements and related roles and responsibilities among the City of Toronto, the TTC, York Region, YRRTC, and Metrolinx in support of the planning and design for the Yonge Subway Extension. Report dated June 9, 2017 from the Chief Administrative Officer now follows: 1. Recommendations It is recommended that: 1. Council authorize the negotiation and execution of a Memorandum of Understanding defining governance arrangements and related roles and responsibilities among the City of Toronto, the TTC, York Region, YRRTC, and Metrolinx in support of the planning and design for the Yonge Subway Extension. 2. Purpose The purpose of this report is to update Council on the City of Toronto report “Advancing the Planning and Design for the Relief Line and Yonge Subway Extension” approved by City of Toronto Council on May 24, 2017, and to authorize staff to enter into agreements with Metrolinx, the City of Toronto and the TTC to advance the planning and design of the Yonge Subway Extension (YSE). Committee of the Whole 1 Finance and Administration June 22, 2017 Advancing the Planning and Design for the Yonge Subway Extension 3.