Mapping Ruling Relations Through Homelessness Organizing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BVA Annual General Meeting - Join Us Published a Month Ago on Wednesday June 9, 2021 at 6:30 Pm

Firefox https://www.bayviewvillage.org/p/Upcoming-Events/article/BVA-Annua... BVA Annual General Meeting - Join Us Published a month ago on Wednesday June 9, 2021 at 6:30 pm. Join us on Zoom to meet your new BVA Executive, learn about our latest initiatives, and for SOMETHING SPECIAL. RSVP Link at: EVENTBRITE (https://www.eventbrite.ca/e/bayview-village-association-annual- general-meeting-tickets-156380344821?aff=ebdssbonlinesearch) OR email [email protected] (mailto:[email protected]) 1 of 2 2021-07-07, 2:09 p.m. Firefox https://www.bayviewvillage.org/p/Upcoming-Events/article/BVA-Annua... 2 of 2 2021-07-07, 2:09 p.m. Bayview Village Association Annual General Meeting June 9, 2021 6:30 pm via Zoom CONTENTS Agenda.................................................................................................................................................... 2 Minutes from BVA AGM June 10, 2020 ................................................................................................... 3 TREASURER’S REPORT........................................................................................................................... 10 Committee Reports............................................................................................................................... 13 BVA Municipal and Government Affairs (MAGA) .............................................................................. 13 BVA Communications Committee Report ........................................................................................ -

Request for a Standing Offer Demande D'offre À

Part - Partie 1 of - de 2 See Part 2 for Clauses and Conditions 1 1 Voir Partie 2 pour Clauses et Conditions RETURN BIDS TO: Title - Sujet RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: Dispersed Meals Bid Receiving Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Date PWGSC W3536-190002/A 2018-07-27 33 City Centre Drive Client Reference No. - N° de référence du client GETS Ref. No. - N° de réf. de SEAG Suite 480C Mississauga W3536-190002 PW-$TOR-009-7570 Ontario File No. - N° de dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME L5B 2N5 TOR-8-41030 (009) Bid Fax: (905) 615-2095 Solicitation Closes - L'invitation prend fin Time Zone Fuseau horaire at - à 02:00 PM Eastern Daylight Saving on - le 2018-09-10 Time EDT Request For a Standing Offer Delivery Required - Livraison exigée Demande d'offre à commandes See Herein Regional Individual Standing Offer (RISO) Address Enquiries to: - Adresser toutes questions à: Buyer Id - Id de l'acheteur Offre à commandes individuelle régionale (OCIR) Holvec, Monique tor009 Telephone No. - N° de téléphone FAX No. - N° de FAX Canada, as represented by the Minister of Public Works and (905)615-2062 ( ) ( ) - Government Services Canada, hereby requests a Standing Offer on behalf of the Identified Users herein. Destination - of Goods, Services, and Construction: Destination - des biens, services et construction: DEPARTMENT OF NATIONAL DEFENCE Le Canada, représenté par le ministre des Travaux Publics et Area Support Unit Toronto Services Gouvernementaux Canada, autorise par la présente, As outlined in SOW une offre à commandes au nom des utilisateurs identifiés énumérés ci-après. -

2018 Annual Report and Financial Statements

A YEAR OF CHANGE CANADA COMPANY MANY WAYS TO SERVE ANNUAL REPORT 2018 CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE FOUNDER AND CHAIR .................................................................................................................................. 3 OUR MISSION IN TRANSITION ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2018 MAJOR ACTIVITIES ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 CLOSING OF THE MILITARY EMPLOYMENT TRANSITION PROGRAMS ............................. 7 OUR PROGRAMS ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 8 GOVERNANCE .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 16 THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS................................................................................................................................................................................................... 17 OUR STRATEGIC PARTNERS -

Authority Meeting #4/16 Was Held at TRCA Head Office, on Friday, May 27, 2016

Authority Meeting #4/16 was held at TRCA Head Office, on Friday, May 27, 2016. The Chair Maria Augimeri, called the meeting to order at 9:32 a.m. PRESENT Kevin Ashe Member Maria Augimeri Chair Jack Ballinger Member Ronald Chopowick Member Vincent Crisanti Member Glenn De Baeremaeker Member Michael Di Biase Vice Chair Jennifer Drake Member Chris Fonseca Member Jack Heath Member Jennifer Innis Member Colleen Jordan Member Matt Mahoney Member Giorgio Mammoliti Member Glenn Mason Member Mike Mattos Member Frances Nunziata Member Linda Pabst Member Anthony Perruzza Member Gino Rosati Member John Sprovieri Member Jim Tovey Member ABSENT Paul Ainslie Member David Barrow Member Justin Di Ciano Member Maria Kelleher Member Jennifer McKelvie Member Ron Moeser Member RES.#A55/16 - MINUTES Moved by: Chris Fonseca Seconded by: Kevin Ashe THAT the Minutes of Meeting #3/16, held on April 22, 2016, be received. CARRIED ______________________________ CITY OF TORONTO REPRESENTATIVE ON THE BUDGET/AUDIT ADVISORY BOARD Ronald Chopowick was nominated by Jack Heath. 110 RES.#A56/16 - MOTION TO CLOSE NOMINATIONS Moved by: Linda Pabst Seconded by: Glenn De Baeremaeker THAT nominations for the City of Toronto representative on the Budget/Audit Advisory Board be closed. CARRIED Ronald Chopowick was declared elected by acclamation as the City of Toronto representative on the Budget/Audit Advisory Board, for a term to end at Annual Meeting #1/17. ______________________________ DELEGATIONS 5.1 A delegation by Martin Medeiros, Regional Councillor, City of Brampton, in regard to item 8.3 - Hurontario-Main Street Light Rail Transit (LRT). 5.2 A delegation by Andrew deGroot, One Brampton, in regard to item 8.3 - Hurontario-Main Street Light Rail Transit (LRT). -

“Mr. Ford Risks Alienating His Key Supporters: Both the Business Community and Fellow Conservatives

Queen’s Park Today – Daily Report November 2, 2020 Quotation of the day “Mr. Ford risks alienating his key supporters: both the business community and fellow conservatives. And Mr. Kenney, experts warn, could quickly set off a public-health disaster if the situation gets out of control.” The Globe and Mail compares Ontario and Alberta's pandemic responses. While Premier Jason Kenney has been criticized for a lighter-touch approach, Premier Doug Ford may be pivoting to Kenney's playbook, asking health officials to draft a plan to ease restrictions in hot spots. Today at Queen’s Park Written by Sabrina Nanji On the schedule The house reconvenes at 9 a.m. for private members’ business; on this morning's docket is second reading of NDP MPP Jeff Burch's Bill 164, Protecting Vulnerable Persons in Supportive Living Accommodation Act. Burch's bill would establish a licensing system for operators of supportive living settings such as nursing homes and children's residences. Bill 202, Soldiers' Aid Commission Act — which shakes up the commission's operations and reporting requirements — was referred back to the house from committee last week and is expected to be called for third reading this afternoon. With a handful of government bills currently at the committee stage, Bill 213 and Bill 207 are the only other ones that could be up for debate today. Bill 213, at second reading, is the red-tape reduction legislation that also gives degree-granting powers and university status to Charles McVety's Canada Christian College. Bill 207 is now back from committee study and poised for third reading; it would align provincial family law with recent federal changes. -

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM41.25

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM41.25 http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2013.MM... Item Tracking Status City Council adopted this item on November 13, 2013 with amendments. City Council consideration on November 13, 2013 MM41.25 ACTION Amended Ward:All Requesting Mayor Ford to respond to recent events - by Councillor Denzil Minnan-Wong, seconded by Councillor Peter Milczyn City Council Decision Caution: This is a preliminary decision. This decision should not be considered final until the meeting is complete and the City Clerk has confirmed the decisions for this meeting. City Council on November 13 and 14, 2013, adopted the following: 1. City Council request Mayor Rob Ford to apologize for misleading the City of Toronto as to the existence of a video in which he appears to be involved in the use of drugs. 2. City Council urge Mayor Rob Ford to co-operate fully with the Toronto Police in their investigation of these matters by meeting with them in order to respond to questions arising from their investigation. 3. City Council request Mayor Rob Ford to apologize for writing a letter of reference for Alexander "Sandro" Lisi, an alleged drug dealer, on City of Toronto Mayor letterhead. 4. City Council request Mayor Ford to answer to Members of Council on the aforementioned subjects directly and not through the media. 5. City Council urge Mayor Rob Ford to take a temporary leave of absence to address his personal issues, then return to lead the City in the capacity for which he was elected. 6. City Council request the Integrity Commissioner to report back to City Council on the concerns raised in Part 1 through 5 above in regard to the Councillors' Code of Conduct. -

7Th Toronto Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery Moss Park Armoury 130 Queen Street East Toronto, Ontario, M5A 1R9

7th Toronto Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery Moss Park Armoury 130 Queen Street East Toronto, Ontario, M5A 1R9 REGIMENTAL SENATE MEETING, 25 January, 2016 Present: HCol Ernest Beno (Chair) LCol Ryan Smid, Commanding Officer, 7th Toronto Regiment MWO Mardie Reyes, RSM 7th Toronto Regiment Col Bill Kalogerakis Col (Retd) Colin Jim Hubel LCol Mike Gomes LCol (Retd) Jim Brazill LCol (Retd) Barry Downs LCol (Retd) Don MacGillivray (By Phone) LCol (Retd) Bryan Sherman (By Phone) Major John Stewart, Regimental Major Lt Nick Arrigo, 7th Tor Band and PMC Officers Mess Capt (Retd) David Burnett – Toronto Gunners (TG) Maj (Retd) Ron Paterson – Limber Gunners (LG) Lt (Retd) Paul Kernohan – Toronto Artillery Foundation (TAF) Capt Garry Hendel, CO 818 Air Cadet Squadron Mrs Patricia Geoffrey, IODE Tony Keenan (Honorary Trustee of the Foundation – Observer) NOTE: These are not intended to be “Minutes” per se; this is more a reflection of issues discussed. 1. Welcome Remarks – Chairman, Hon Col Beno gave welcoming remarks and updated the Senate on issues of interest. He thanked the Regimental Family for their continuous support to the soldiers of 7th Toronto Regiment. Hon Col welcomed the IODE (Imperial Order of Daughters of the Empire) UBIQUE Chapter to the Regimental Family. He welcomed those on the phone on conference call – something we’ll use more in the future. He reminded all that he wishes to keep discussions at the higher (Regimental strategic) level, but it is equally important that we share information and collaborate. So, the aim is not just to share info, but it is to coordinate and collaborate, and make decisions on those matters of significant importance to the Regimental Family as a whole. -

Communityommunity DDNDND 10%10% Offoff Ppharmasaveharmasave Brandbrand

Volume 57 Number 22 | May 28, 2012 Prroudlyoudly sservingerving oourur ccommunityommunity DDNDND 110%0% ooffff PPharmasaveharmasave BBrandrand Thank you for shopping locally! Just 3 minutes from the Base. MARPAC NEWS CFB Esquimalt, Victoria, B.C. Esquimalt Plaza, 1153 Esquimalt Rd. 250-388-6451 www.lookoutnewspaper.com CCommunityommunity aartrt An Aboriginal art display was unveiled in the Wardroom last week in honour of Aboriginal Awareness Week, and the strong link between Aboriginal history and CFB Esquimalt. Some artists gifted their work, while others have loaned it to the base; so, over time this display will change. Pictured here, artist Clarence Dick Jr poses beside the carved panel he made for this display. Photo by Shelley Lipke, Lookout www.canex.ca We proudly serve the Canadian Forces Community No Interest As a military family we understand HIGH PERFORMANCE LOW PRESSURE Credit Plan your cleaning needs during ongoing service, deployment and relocation. www.mollymaid.ca MILITARY We offer those serving in the military and DND a DISCOUNT: specialty discount. Not valid with any other offer. Month terms BAY STREET LOCATION JACKLIN ROAD LOCATION 708 Bay St. Victoria BC 2988 Jacklin Rd. Victoria BC (250) 744-3427 (250) 389 1326 (250) 474 7133 [email protected] 2 • LOOKOUT May 28, 2012 @ Navy10kEsq EsquimaltNavy10K Financial security planning products www.Navy10kEsquimalt.ca CFB ESQUIMALT • Segregated fund policies, RRSPs & TFSAs • Individual life insurance SUNDAY JUNE 3, 2012 • Payout annuities, RRIFs and LIFs • Business insurance • Individual disability insurance • Group insurance • Individual critical illness insurance • Group retirement plans • Individual health and dental insurance • Mortgages Steve Hall Financial Security Advisor 250-932-7777 I Cell: 250: 250-732-5715 [email protected] I www.stevelhall.com. -

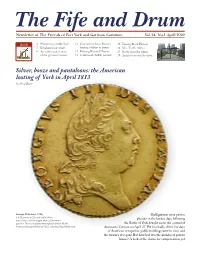

Fife and Drum April 2020 John and Penelope Beikie Lived in the House in the Middle of This Tranquil Scene Painted Just After the War

Newsletter of The Friends of Fort York and Garrison Common Vol.24, No.1 April 2020 2 Plundering muddy York 12 Communist from Toronto 15 Tasting Black History 7 Retaliation for what? leading soldiers in Spain 16 Mrs. Traill’s Advice 9 An early modern view 14 Retiring Richard Haynes 17 Notes from the editor of the garrison’s homes 15 Traditional challah prevails 18 Architecture on television Silver, booze and pantaloons: the American looting of York in April 1813 by Fred Blair George III Guinea, 1795, is 8.35 grams of 22 carat gold; diam- Gold guineas were perfect eter 24 mm, a little bigger than a Canadian plunder in the lawless days following quarter. These circulated throughout British North the Battle of York, fought across the ground of America during the War of 1812. Courtesy RoyalMint.com. downtown Toronto on April 27. We lost badly. After five days of American occupation, public buildings were in ruins and the treasury was gone. But how bad was the plunder of private homes? A look at the claims for compensation, p.2. ieutenant Ely Playter, a farmer in the 3rd York Militia, government warehouses – after they’d been emptied of trophies wrote in his diary that he was just leaving the eastern gate and useful stores – were soon reduced to ashes, by accident or of the fort when the great magazine “Blew up.” Although design. But these were public buildings. How severe was the Lit killed more U.S. soldiers than the fighting itself, ending the looting of private homes in the wake of the battle? Battle of York, the vast explosion left Ely stunned but otherwise This is an examination of the claims filed by individuals for unharmed. -

News Release May 25, 2020 Councillors Welcome New Bike

News Release May 25, 2020 Councillors welcome new bike lanes along Bloor and University as part of City’s COVID-19 Response Toronto City Councillors Joe Cressy (Spadina-Fort York), Mike Layton (University-Rosedale), and Kristyn Wong-Tam (Toronto Centre) welcomed tHe announcement of new separated bike lanes tHis morning along Bloor Street and University Avenue, as part of tHe City’s ActiveTO program. THese bike lanes will make it easier for residents and front-line workers to cycle to work and practice pHysical distancing. As we begin to transition to recovery in Toronto and more businesses and workplaces open back up, How we will get around is a pressing challenge. For safe pHysical distancing we need to create alternative and safe metHods of transportation. Switching to driving isn’t an option for many, and even if it was, tHe resulting gridlock will grind traffic to a Halt, strangling our city and economy. It’s time for a new approach. Bike lanes on University Avenue (tHrougH Queen’s Park Crescent) and on Bloor Street will provide relief to two subway lines, creating more space on tHe subway for tHose wHo need to ride transit, and offering a new cycling option tHat is safe and uses our limited road space as efficiently as possible to move tHe most people. THe new separated bike lanes on tHese routes will connect cyclists to many of tHe area’s Hospitals and HealtH care facilities. Doctors for Safe Cycling, representing many pHysicians from downtown Hospitals, issued a letter earlier tHis montH asking for protected bike lanes, so tHat HealtH care workers, clients, and otHers can commute safely to tHe Hospital district by bike. -

Toronto City Council Enviro Report Card 2010-2014

TORONTO CITY COUNCIL ENVIRO REPORT CARD 2010-2014 TORONTO ENVIRONMENTAL ALLIANCE • JUNE 2014 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY hortly after the 2010 municipal election, TEA released a report noting that a majority of elected SCouncillors had committed to building a greener city. We were right but not in the way we expected to be. Councillors showed their commitment by protecting important green programs and services from being cut and had to put building a greener city on hold. We had hoped the 2010-14 term of City Council would lead to significant advancement of 6 priority green actions TEA had outlined as crucial to building a greener city. Sadly, we’ve seen little - if any - advancement in these actions. This is because much of the last 4 years has been spent by a slim majority of Councillors defending existing environmental policies and services from being cut or eliminated by the Mayor and his supporters; programs such as Community Environment Days, TTC service and tree canopy maintenance. Only in rare instances was Council proactive. For example, taking the next steps to grow the Greenbelt into Toronto; calling for an environmental assessment of Line 9. This report card does not evaluate individual Council members on their collective inaction in meeting the 2010 priorities because it is almost impossible to objectively grade individual Council members on this. Rather, it evaluates Council members on how they voted on key environmental issues. The results are interesting: • Average Grade: C+ • The Mayor failed and had the worst score. • 17 Councillors got A+ • 16 Councillors got F • 9 Councillors got between A and D In the end, the 2010-14 Council term can be best described as a battle between those who wanted to preserve green programs and those who wanted to dismantle them. -

A Survey of Homelessness Laws

The Forum September 2020 Is a House Always a Home?: A Survey of Homelessness Laws Marlei English J.D. Candidate, SMU Dedman School of Law, 2021; Staff Editor for the International Law Review Association Find this and additional student articles at: https://smulawjournals.org/ilra/forum/ Recommended Citation Marlei English, Is a House Always a Home?: A Survey of Homelessness Laws (2020) https://smulawjournals.org/ilra/forum/. This article is brought to you for free and open access by The Forum which is published by student editors on The International Law Review Association in conjunction with the SMU Dedman School of Law. For more information, please visit: https://smulawjournals.org/ilra/. Is a House Always a Home?: A Survey of Homelessness Laws By: Marlei English1 March 6, 2020 Homelessness is a plague that spares no country, yet not a single country has cured it. The type of legislation regarding homelessness in a country seems to correlate with the severity of its homelessness problem. The highly-variative approaches taken by each country when passing their legislation can be roughly divided into two categories: aid-based laws and criminalization laws. Analyzing how these homelessness laws affect the homeless community in each country can be an important step in understanding what can truly lead to finding the “cure” for homelessness rather than just applying temporary fixes. I. Introduction to the Homelessness Problem Homelessness is not a new issue, but it is a current, and pressing issue.2 In fact, it is estimated that at least 150 million individuals are homeless.3 That is about two percent of the population on Earth.4 Furthermore, an even larger 1.6 billion individuals may be living without adequate housing.5 While these statistics are startling, the actual number of individuals living without a home could be even larger because these are just the reported and observable numbers.