COLO FINAL 062111.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jamestown Long Range Interpretive Plan (LRIP)

Jamestown Colonial National Historical Park Long Range Interpretive Plan Update July 2009 Prepared for the National Park Service by Ron Thomson, Compass Table of Contents Part 1: Foundation Introduction 4 Background 6 Park in 2009 12 Purpose & Significance 19 Interpretive Themes 22 Audiences 29 Audience Experiences 32 Issues & Initiatives 35 Part 2: Taking Action Introduction 38 Projects from 2000 Plan 38 Current Area of Focus 40 Enhance Existing Resources 40 Anniversaries/Events 43 Linking Research, Interpretation & Sales 44 Education Programs 45 Technology for Interpretation 46 Evaluation & Professional Standards 47 Staffing & Training 47 Library, Collection & Research Needs 48 Implementation Charts 52 Participants 59 Appendices 1. Other Planning Documents 60 2. Partner Mission Statements 64 3. Second Century Goals 66 4. Interpretation & Education Renaissance Action Plan 69 5. Children in Nature 71 2 Part 1 The Foundation 3 Introduction The Long Range Interpretive Plan A Long Range Interpretive Plan (LRIP) provides a 5+ year vision for a park’s interpretive program. A facilitator skilled in interpretive planning works with park staff, partners, and outside consultants to prepare a plan that is consistent with other current planning documents. Part 1 of the LRIP establishes criteria against which existing and proposed personal services and media can be measured. It identifies themes, audiences, audience experiences, and issues. Part 2 describes the mix of services and facilities that are necessary to achieve management goals and interpretive mission. It includes implementation charts that plot a course of action, assign responsibilities, and offer a schedule of activity. When appropriate, Appendices provide more detailed discussions of specific topics. The completed LRIP forms a critical part of the more inclusive Comprehensive Interpretive Plan (CIP). -

CAPE HENRY MEMORIAL VIRGINIA the Settlers Reached Jamestown

CAPE HENRY MEMORIAL VIRGINIA the settlers reached Jamestown. In the interim, Captain Newport remained in charge. The colonists who established Jamestown On April 27 a second party was put ashore. They spent some time "recreating themselves" made their first landing in Virginia and pushed hard on assembling a small boat— a "shallop"—to aid in exploration. The men made short marches in the vicinity of the cape and at Cape Henry on April 26, 1607 enjoyed some oysters found roasting over an Indian campfire. The next day the "shallop" was launched, and The memorial cross, erected in 1935. exploration in the lower reaches of the Chesa peake Bay followed immediately. The colonists At Cape Henry, Englishmen staged Scene scouted by land also, and reported: "We past Approaching Chesapeake Bay from the south through excellent ground full of Flowers of divers I, Act I of their successful drama of east, the Virginia Company expedition made kinds and colours, and as goodly trees as I have conquering the American wilderness. their landfall at Cape Henry, the southernmost seene, as Cedar, Cipresse, and other kinds . Here, "about foure a clocke in the morning" promontory of that body of water. Capt. fine and beautiful Strawberries, foure time Christopher Newport, in command of the fleet, bigger and better than ours in England." on April 26,1607, some 105 sea-weary brought his ships to anchor in protected waters colonists "descried the Land of Virginia." just inside the bay. He and Edward Maria On April 29 the colonists, possibly using Wingfield (destined to be the first president of English oak already fashioned for the purpose, They had left England late in 1606 and the colony), Bartholomew Gosnold, and "30 others" "set up a Crosse at Chesupioc Bay, and named spent the greater part of the next 5 months made up the initial party that went ashore to that place Cape Henry" for Henry, Prince of in the strict confines of three small ships, see the "faire meddowes," "Fresh-waters," and Wales, oldest son of King James I. -

Program Summary March 21, 2006 08:49:02

Program Summary March 21, 2006 08:49:02 11113300 New Hampshire Dept. of Environmental Services Organizational Program Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) Chemical, physical, and bacteriological river quality sampling program (annual - typically June, July, and August). Project ARMP1990 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1990 Project ARMP1991 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1991 Project ARMP1992 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1992 Project ARMP1993 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1993 Project ARMP1994 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1994 Project ARMP1995 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1995 Project ARMP1996 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1996 Project ARMP1997 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1997 Project ARMP1998 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1998 Project ARMP1999 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1999 Project ARMP2000 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 2000 Project ARMP2001 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 2001 Project ARMP2002 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 2002 Project ARMP2003 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 2003 Project ARMP2004 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 2004 Organizational Program New Hampshire Public Beach Inspection Program To inspect and monitor water quality at public beaches throughout the state in order to protect public health. To ensure bacteria levels at public beaches are below state standards for recreational waters. Project BEACH NH Public Beach Inspection Program Project -

FIELDREPORT Mid-Atlantic Region | Spring-Summer 2015

FIELDREPORT Mid-Atlantic Region | Spring-Summer 2015 In Harm’s Way Down to the Wire Proposed Pipelines Protecting Jamestown’s Historic Character Threaten Our National Parks By Pam Goddard By Pam Goddard he historic setting of Jamestown women, forever disrupting these First Island, site of America’s first permanent American cultures—and laying the foundation ncreased hydraulic fracturing, a.k.a. English settlement, is one of the last for today’s United States. “fracking,” throughout the country T places in America where a new super-sized has brought a new challenge to I electric transmission line should be built. In 2012, Dominion Virginia Power announced national parks and forests—new Incredibly, one of the nation’s most influential plans to build a new electric transmission line proposals to build hundreds of miles energy companies seeks to construct such amidst these national treasures. Dominion’s of pipelines to carry natural gas across proposal would place 17 lighted towers up multiple states and through our national a project this year—unless we can persuade decision makers to require Dominion to 295 feet tall—nearly the height of the parks. In Virginia alone, three pipeline Statue of Liberty—across the James River. proposals could cross the Appalachian Virginia Power to pursue alternatives. Not only would this line degrade the region’s National Scenic Trail and Blue Ridge Visitors discover an abundance of rich history historic character, it would threaten key Parkway, as well as the George and outstanding beauty at Colonial National natural resources. Washington, Jefferson, and Monongahela continued on page 3 National Forests. -

Heritage Framework Book

Chapter Nine Chesapeake Metropolis, 1930 to 2000 New World Depression Era World War II Cold War Economic Order 1930 to 1939 1939 to 1945 1947 to 1989 1989 to 2000 1950- 1965- 1930 1933 1939 1940 1941 1945 1947 1953 1952 1973 1973 1983 1989 1990 2000 ||||||||||||||| Regional | WWII | America WWII | Korean | Vietnam | U.S. EPA | Regional | population | begins in | enters ends | War | War | establishes | population | reaches | Europe | WW II || |Chesapeake | reaches | 5.0 million || Cold War Chesapeake | Bay Program | 10.5million | Franklin | begins Bay Bridge ||| Delano Regional opens Chesapeake Soviet Union Regional Roosevelt population Bay Bridge- collapses population first elected nears Tunnel ending reaches president 5.5 million opens Cold War 12.0 million AN ECOLOGY OF PEOPLE SIGNIFICANT EVENTS AND PLACE ▫ 1930–regional ▫ 1948 to 1950–Alger ▫ 1968–riots in population reaches Hiss spy case Washington, Ⅺ PEOPLE 5 million ▫ 1950–postwar Baltimore, and other ▫ 1932–Federal troops migration combined Chesapeake cities The 5 million inhabitants of the Chesa- disperse bonus with baby boom ▫ 1970–Amtrak peake Bay region faced a terrible para- marchers in increase regional established Washington population to dox in 1930 (see Map 11). On the surface, ▫ 1972–Hurricane ▫ 1933–Franklin 7 million Agnes devastates nothing seemed to have changed. Delano Roosevelt ▫ 1950 to 1953– region Although population pressure had elected to first term Korean War fought ▫ 1973–Chesapeake as president clearly left a mark on the region, fish still between U. S.–led Bay Bridge–Tunnel ▫ 1935–Social Security United Nations opens teemed in Bay waters, and farm fields Act passed by troops and ▫ 1973–OPEC oil Congress Communist North still swelled with produce ready for mar- embargo creates ▫ 1939–World War II Korean and Chinese ket. -

NOMINATION FORM for NPS USE ONLY ENTRVWUMBER DATE (Continuation Sheet) I Fn"Mb.T .I1 ."T,L..J 7 A

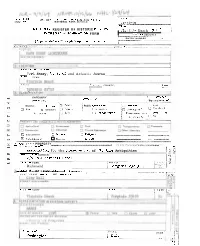

ST0 TC: Fmrm ;0-300 UNIT ED STATC5QEgARTMFNT OF +HE INTFRlDR (July 19691 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE i COUN TY. ', I NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES ' IrJrgi-nia Beach (city) I CNYENTQUY - NOMENATIUH FORM TOR NPS USE ONLY I - -1 ENTRY NUMBER DATK? i (Type entries complete applicab ie all - secfions) I , , , A . m -. * - . A A . ,**. ' ',- . -. Y I I . 1 STREET I\NC NUUDER: I Far5 Story, U1 S. 60 and Atlantic Avenue CITY FFI TOWN. t CODE COUNTY, CODC - --+.- - I ICCESSIBLE CATEGORY QWNFRSHlP i I I TO THE PUBLIC (Chock one) -. District 0 Bullding Public Gcquisitian~ r_l Occvpled Q a++ Structure Private • Clb~~ct 0 B-img Csnridstad Pvcrsru-i.on lark Unrestrict.6 1 I Educational C Milivory a Rtligiws En?artainment Mus*um a Sciu~ific --- /1 m - -- 1 r4, OWNER OF PROPERTY c -+ 1 .- - " '--- I OWUER'S MAMC I ml Assmiation for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities 1l5'fRLk.T AND NUMBER! c/o Jshn Marshall Hotcl - CNTY aw TO WN. ST~TEI. Richmond Virginia 23213 . - - . .-.- -- .' .--, LOCATION OF L EGAL DESCRIPTION- --.- ..--- . I k. - - ....I .. > .- , , , , . .- _ - __1 ;T@URTHQY~~,RRGlSTRY OF DEEDS, ETC C1 TY OR TOWN! lsTArE ---- - ' CITY CIA TlOWNL I CODE WasMngtoa 1 Q.C. L.!" 1 Excellsnt Good Foir Deteriorated Ruins U Unexposed CoNolTlo~ -- (Check One) (Check One) AII~,=~ U~~I,~.~~ rn n MOW origino~sits DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND OR1GINAL (If ~~OW~)PHYS!CALAPPEARANCE a. BACKGROUND INFORMATION: Cape Henry Lighthouse is the first light- house structure authorized, fully completed, and lighted by the newly organized Federal Government. It is an octagonal stone structure, faced with hewn or hammer-dressed stone--the first of three lighthouses to be built by John McComb, Jr. -

The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933-1942: an Administrative History. INSTITUTION National Park Service (Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 266 012 SE 046 389 AUTHOR Paige, John C. TITLE The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933-1942: An Administrative History. INSTITUTION National Park Service (Dept. of Interior), Washington, D.C. REPORT NO NPS-D-189 PUB DATE 85 NOTE 293p.; Photographs may not reproduce well. PUB TYPE Reports - Descriptive (141) -- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Conservation (Environment); Employment Programs; *Environmental Education; *Federal Programs; Forestry; Natural Resources; Parks; *Physical Environment; *Resident Camp Programs; Soil Conservation IDENTIFIERS *Civilian Conservation Corps; Environmental Management; *National Park Service ABSTRACT The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) has been credited as one of Franklin D. Roosevelt's most successful effortsto conserve both the natural and human resources of the nation. This publication provides a review of the program and its impacton resource conservation, environmental management, and education. Chapters give accounts of: (1) the history of the CCC (tracing its origins, establishment, and termination); (2) the National Park Service role (explaining national and state parkprograms and co-operative planning elements); (3) National Park Servicecamps (describing programs and personnel training and education); (4) contributions of the CCC (identifying the major benefits ofthe program in the areas of resource conservation, park and recreational development, and natural and archaeological history finds); and (5) overall -

Colonial Parkway a Triple Memorial of History Is Here Made Accessible by a Scenic and Historically Rich Parkway

COLONIAL PAR KWAY IAMSB uko. 't14,4 Jamestown 0 94%cb 44, c°' 1L viRGirrit, Williamsburg Colonial National Historical Park VIRGINIA Colonial Parkway A triple memorial of history is here made accessible by a scenic and historically rich parkway N THE Virginia Peninsula three fa- Williamsburg Information Center. These mous places—Jamestown, Williams- are the best points of departure for seeing 0 burg, and Yorktown—form a triangle the areas. only 14 miles at the base. Here, between The parkway route is outward from James- the James and York Rivers, is compressed a town Island over a sandbar to Glasshouse great deal of American history. The found- Point An isthmus existed there in colonial ing of the first permanent English settlement times. For the colonists, it was the way to in 1607 at Jamestown, Va.; the establish- unoccupied lands awaiting beyond. In the ment there of the first representative form vicinity of the Glasshouse and Virginia's Fes- of government in the New World; the flower- tival Park, Colonial Parkway bends sharply ing of colonial culture and growth of revolu- to cross Powhatan Creek and then courses tionary sentiment at Williamsburg; and the eastward along Back River and the Thor- winning of American independence at York- oughfare, which separate Jamestown Island town are historical milestones. from the mainland. After following the Each place has a thrilling story of its own. James River for 3 miles, the parkway at Yet, they are connected stories, for things College Creek turns inland through the woods that happened at Jamestown led directly to toward Williamsburg. -

Packets to the Board

Carroll County Government Additional Appropriation Worksheet – FY2011 Appropriation for: The Carroll County School Board requests the Carroll County Board of Supervisors appropriate the following grant and/or additional funds, which have become available, to the categories listed below in the 2010-2011 Carroll County School Operational Budget. The revenue account number will be determined by the VA DOE’s OMEGA system when funds are released. Date Approved by Board of Supervisors: 12/14/2010 Revenue Source: Sch Fund - Federal Funds - 3-205 (acct to be determined) $692,441.00 Expenditure line item to be adjusted (include account number): Sch Fund – Undistributed Sch Exp 4-205-060000-999 $692,441.00 Expenditure Budget Adjustment made by: ___________________________________ Date: ______________________ November 11, 2010 The Carroll County Board of Supervisors held their regular monthly meeting on, November 11, 2010 in the Board Meeting Room of the Carroll County Governmental Center. Present were: Dr. Thomas W. Littrell David V. Hutchins W.S. “Sam” Dickson Andrew S. Jackson N. Manus McMillian Gary Larrowe, County Administrator Nikki Shank, Assistant Administrator Ronald L. Newman, Assistant Administrator Dr. Littrell called the meeting to order at 4:00 p.m. Dr. Littrell told that we would like to recognize Randy Webb who is here with the FFA from the high school. CARROLL COUNTY FFA Mr. Webb told that it is a pleasure to be here and they wanted to give thanks for the support and contribution that the Board made. He told that the students have worked hard and he would like to turn it over to the Chapter President. -

1976 Bicentennial Mckinley South Buttress Expedition

THE MOUNTAINEER • Cover:Mowich Glacier Art Wolfe The Mountaineer EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Verna Ness, Editor; Herb Belanger, Don Brooks, Garth Ferber. Trudi Ferber, Bill French, Jr., Christa Lewis, Mariann Schmitt, Paul Seeman, Loretta Slater, Roseanne Stukel, Mary Jane Ware. Writing, graphics and photographs should be submitted to the Annual Editor, The Mountaineer, at the address below, before January 15, 1978 for consideration. Photographs should be black and white prints, at least 5 x 7 inches, with caption and photo grapher's name on back. Manuscripts should be typed double· spaced, with at least 1 Y:z inch margins, and include writer's name, address and phone number. Graphics should have caption and artist's name on back. Manuscripts cannot be returned. Properly identified photographs and graphics will be returnedabout June. Copyright © 1977, The Mountaineers. Entered as second·class matter April8, 1922, at Post Office, Seattle, Washington, under the act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly, except July, when semi-monthly, by The Mountaineers, 719 Pike Street,Seattle, Washington 98101. Subscription price, monthly bulletin and annual, $6.00 per year. ISBN 0-916890-52-X 2 THE MOUNTAINEERS PURPOSES To explore and study the mountains, forests, and watercourses of the Northwest; To gather into permanentform the history and tra ditions of thisregion; To preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise the natural beauty of NorthwestAmerica; To make expeditions into these regions in fulfill ment of the above purposes; To encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all loversof outdoor life. 0 � . �·' ' :···_I·:_ Red Heather ' J BJ. Packard 3 The Mountaineer At FerryBasin B. -

Interior Department” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 69, folder “Interior Department” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 69 of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR and Mrs. Thomas S. Kleppe cordially invite you to attend a reception and preview of the DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR'S BICENTENNIAL ART EXHIBITION AMERICA 1976 at the Corcoran Gallery of Art Washington, D.C. Monday, April26, 1976 6 to 8 P.M. Black tie optional Some items in this folder were not digitized because it contains copyrighted materials. Please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library for access to these materials. The Department of the Interior has commissioned 45 artists in an ambitious project that has proved the wisdom of government's direct involvement in art and has provoked a new look at the magnificence of the American land l Painting the public lands by Kay Larson hopes about government's direct in volvement in art. -

Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Historic Resource Study Great Smoky Mountains National Park

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Service National Park Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Historic Resource Study Resource Historic Park National Mountains Smoky Great Historic Resource Study | Volume 1 April 2016 VOL Historic Resource Study | Volume 1 1 As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering sound use of our land and water resources; protecting our fish, wildlife, and biological diversity; preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historic places; and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to ensure that their development is in the best interests of all our people by encouraging stewardship and citizen participation in their care. The department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island territories under U.S. administration. GRSM 133/134404/A April 2016 GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 FRONT MATTER ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..........................................................................................................