Heritage Framework Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Bay Civil Engineering Projects

History of Bay Civil Engineering Projects Port of Baltimore The rise of Baltimore from a sleepy town trading in tobacco to a city rivaling Philadelphia, Boston, and New York began when Dr. John Stevenson, a prominent Baltimore physician and merchant, began shipping flour to Ireland. The success of this seemingly insignificant venture opened the eyes of many Baltimoreans to the City’s most extraordinary advantage– a port nestled alongside a vast wheat growing countryside, significantly closer to this rich farm land than Philadelphia. During the Revolutionary War, Baltimore contributed an essential ingredient for victory: naval superiority. By the 1770s, Baltimore had built the most maneuverable ships in the world. These ships penetrated British blockades and outran pirates, privateers, and the Royal British Navy. The agility and speed of these ships allowed Baltimore merchants to continue trading during the Revolutionary War, which in turn helped to win the war and to propel Baltimore’s growth from 564 houses in 1774 to 3,000 houses in the mid 1790s. This engraving of Baltimore was published in Paris and New York around 1834. Since 1752, Federal Hill has been the vantage point from which to view Baltimore. As Baltimore’s port grew, its trade routes were extended to the Ohio Valley. In 1806 the Federal Government authorized the building of the National Road from the Ohio River to Cumberland, Maryland. In turn, Baltimore businessmen built turnpike roads from Baltimore to Cumberland, effectively completing the Maryland portion of the National Road. The Road quickly became Baltimore’s economic lifeline to the fertile lands of the Ohio Valley. -

Jamestown Long Range Interpretive Plan (LRIP)

Jamestown Colonial National Historical Park Long Range Interpretive Plan Update July 2009 Prepared for the National Park Service by Ron Thomson, Compass Table of Contents Part 1: Foundation Introduction 4 Background 6 Park in 2009 12 Purpose & Significance 19 Interpretive Themes 22 Audiences 29 Audience Experiences 32 Issues & Initiatives 35 Part 2: Taking Action Introduction 38 Projects from 2000 Plan 38 Current Area of Focus 40 Enhance Existing Resources 40 Anniversaries/Events 43 Linking Research, Interpretation & Sales 44 Education Programs 45 Technology for Interpretation 46 Evaluation & Professional Standards 47 Staffing & Training 47 Library, Collection & Research Needs 48 Implementation Charts 52 Participants 59 Appendices 1. Other Planning Documents 60 2. Partner Mission Statements 64 3. Second Century Goals 66 4. Interpretation & Education Renaissance Action Plan 69 5. Children in Nature 71 2 Part 1 The Foundation 3 Introduction The Long Range Interpretive Plan A Long Range Interpretive Plan (LRIP) provides a 5+ year vision for a park’s interpretive program. A facilitator skilled in interpretive planning works with park staff, partners, and outside consultants to prepare a plan that is consistent with other current planning documents. Part 1 of the LRIP establishes criteria against which existing and proposed personal services and media can be measured. It identifies themes, audiences, audience experiences, and issues. Part 2 describes the mix of services and facilities that are necessary to achieve management goals and interpretive mission. It includes implementation charts that plot a course of action, assign responsibilities, and offer a schedule of activity. When appropriate, Appendices provide more detailed discussions of specific topics. The completed LRIP forms a critical part of the more inclusive Comprehensive Interpretive Plan (CIP). -

CAPE HENRY MEMORIAL VIRGINIA the Settlers Reached Jamestown

CAPE HENRY MEMORIAL VIRGINIA the settlers reached Jamestown. In the interim, Captain Newport remained in charge. The colonists who established Jamestown On April 27 a second party was put ashore. They spent some time "recreating themselves" made their first landing in Virginia and pushed hard on assembling a small boat— a "shallop"—to aid in exploration. The men made short marches in the vicinity of the cape and at Cape Henry on April 26, 1607 enjoyed some oysters found roasting over an Indian campfire. The next day the "shallop" was launched, and The memorial cross, erected in 1935. exploration in the lower reaches of the Chesa peake Bay followed immediately. The colonists At Cape Henry, Englishmen staged Scene scouted by land also, and reported: "We past Approaching Chesapeake Bay from the south through excellent ground full of Flowers of divers I, Act I of their successful drama of east, the Virginia Company expedition made kinds and colours, and as goodly trees as I have conquering the American wilderness. their landfall at Cape Henry, the southernmost seene, as Cedar, Cipresse, and other kinds . Here, "about foure a clocke in the morning" promontory of that body of water. Capt. fine and beautiful Strawberries, foure time Christopher Newport, in command of the fleet, bigger and better than ours in England." on April 26,1607, some 105 sea-weary brought his ships to anchor in protected waters colonists "descried the Land of Virginia." just inside the bay. He and Edward Maria On April 29 the colonists, possibly using Wingfield (destined to be the first president of English oak already fashioned for the purpose, They had left England late in 1606 and the colony), Bartholomew Gosnold, and "30 others" "set up a Crosse at Chesupioc Bay, and named spent the greater part of the next 5 months made up the initial party that went ashore to that place Cape Henry" for Henry, Prince of in the strict confines of three small ships, see the "faire meddowes," "Fresh-waters," and Wales, oldest son of King James I. -

Program Summary March 21, 2006 08:49:02

Program Summary March 21, 2006 08:49:02 11113300 New Hampshire Dept. of Environmental Services Organizational Program Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) Chemical, physical, and bacteriological river quality sampling program (annual - typically June, July, and August). Project ARMP1990 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1990 Project ARMP1991 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1991 Project ARMP1992 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1992 Project ARMP1993 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1993 Project ARMP1994 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1994 Project ARMP1995 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1995 Project ARMP1996 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1996 Project ARMP1997 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1997 Project ARMP1998 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1998 Project ARMP1999 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 1999 Project ARMP2000 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 2000 Project ARMP2001 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 2001 Project ARMP2002 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 2002 Project ARMP2003 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 2003 Project ARMP2004 Ambient River Monitoring Program (ARMP) - 2004 Organizational Program New Hampshire Public Beach Inspection Program To inspect and monitor water quality at public beaches throughout the state in order to protect public health. To ensure bacteria levels at public beaches are below state standards for recreational waters. Project BEACH NH Public Beach Inspection Program Project -

FIELDREPORT Mid-Atlantic Region | Spring-Summer 2015

FIELDREPORT Mid-Atlantic Region | Spring-Summer 2015 In Harm’s Way Down to the Wire Proposed Pipelines Protecting Jamestown’s Historic Character Threaten Our National Parks By Pam Goddard By Pam Goddard he historic setting of Jamestown women, forever disrupting these First Island, site of America’s first permanent American cultures—and laying the foundation ncreased hydraulic fracturing, a.k.a. English settlement, is one of the last for today’s United States. “fracking,” throughout the country T places in America where a new super-sized has brought a new challenge to I electric transmission line should be built. In 2012, Dominion Virginia Power announced national parks and forests—new Incredibly, one of the nation’s most influential plans to build a new electric transmission line proposals to build hundreds of miles energy companies seeks to construct such amidst these national treasures. Dominion’s of pipelines to carry natural gas across proposal would place 17 lighted towers up multiple states and through our national a project this year—unless we can persuade decision makers to require Dominion to 295 feet tall—nearly the height of the parks. In Virginia alone, three pipeline Statue of Liberty—across the James River. proposals could cross the Appalachian Virginia Power to pursue alternatives. Not only would this line degrade the region’s National Scenic Trail and Blue Ridge Visitors discover an abundance of rich history historic character, it would threaten key Parkway, as well as the George and outstanding beauty at Colonial National natural resources. Washington, Jefferson, and Monongahela continued on page 3 National Forests. -

The Recreation the Delmarva Peninsula by David

THE RECREATION POTENTIAL OF THE DELMARVA PENINSULA BY DAVID LEE RUBIN S.B., Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1965) SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOT THE DEGREE OF MASTER IN CITY PLANNING at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June, 1966 Signature of Author.,.-.-,.*....... .. .*.0 .. .. ...... .. ...... ... Department of City and Regional Planning May 23, 1966 Certified by.... ....... .- -*s.e- Super....... Thesis Supervisor Accepted by... ... ...tire r'*n.-..0 *10iy.- .. 0....................0 Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students 038 The Recreation Potential of the Delmarva Peninsula By David Lee Rubin Submitted to the Department of City and Regional Planning on 23 May, 1966 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning. rhis thesis is a plan for the development of Lne recreation potential of the Delmarva Peninsyla, the lower counties of Delaware and the Eastern Shore of Maryland and Virginia, to meet the needs of the Megalopolitan population. Before 1952, the Delmarva Peninsula was isolated, and no development of any kind occurred. The population was stable, with no in migration, and the attitudes were rural. The economy was sagging. Then a bridge was built across the Chesapeake Bay, and the peninsula became a recreation resource for the Baltimore and Washington areas. Ocean City and Rehoboth, the major resorts, have grown rapidly since then. In 1964, the opening of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel further accellerated growth. There are presently plans for the development of a National Seashore on Assateague Island, home of the Chincoteague ponies, as well as state parks along the Chesapeake Bay, and such facilities as a causeway through the ocean and a residential complex in the Indian River Bay. -

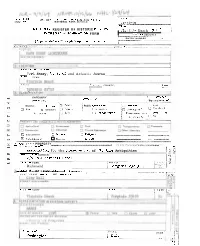

NOMINATION FORM for NPS USE ONLY ENTRVWUMBER DATE (Continuation Sheet) I Fn"Mb.T .I1 ."T,L..J 7 A

ST0 TC: Fmrm ;0-300 UNIT ED STATC5QEgARTMFNT OF +HE INTFRlDR (July 19691 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE i COUN TY. ', I NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES ' IrJrgi-nia Beach (city) I CNYENTQUY - NOMENATIUH FORM TOR NPS USE ONLY I - -1 ENTRY NUMBER DATK? i (Type entries complete applicab ie all - secfions) I , , , A . m -. * - . A A . ,**. ' ',- . -. Y I I . 1 STREET I\NC NUUDER: I Far5 Story, U1 S. 60 and Atlantic Avenue CITY FFI TOWN. t CODE COUNTY, CODC - --+.- - I ICCESSIBLE CATEGORY QWNFRSHlP i I I TO THE PUBLIC (Chock one) -. District 0 Bullding Public Gcquisitian~ r_l Occvpled Q a++ Structure Private • Clb~~ct 0 B-img Csnridstad Pvcrsru-i.on lark Unrestrict.6 1 I Educational C Milivory a Rtligiws En?artainment Mus*um a Sciu~ific --- /1 m - -- 1 r4, OWNER OF PROPERTY c -+ 1 .- - " '--- I OWUER'S MAMC I ml Assmiation for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities 1l5'fRLk.T AND NUMBER! c/o Jshn Marshall Hotcl - CNTY aw TO WN. ST~TEI. Richmond Virginia 23213 . - - . .-.- -- .' .--, LOCATION OF L EGAL DESCRIPTION- --.- ..--- . I k. - - ....I .. > .- , , , , . .- _ - __1 ;T@URTHQY~~,RRGlSTRY OF DEEDS, ETC C1 TY OR TOWN! lsTArE ---- - ' CITY CIA TlOWNL I CODE WasMngtoa 1 Q.C. L.!" 1 Excellsnt Good Foir Deteriorated Ruins U Unexposed CoNolTlo~ -- (Check One) (Check One) AII~,=~ U~~I,~.~~ rn n MOW origino~sits DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND OR1GINAL (If ~~OW~)PHYS!CALAPPEARANCE a. BACKGROUND INFORMATION: Cape Henry Lighthouse is the first light- house structure authorized, fully completed, and lighted by the newly organized Federal Government. It is an octagonal stone structure, faced with hewn or hammer-dressed stone--the first of three lighthouses to be built by John McComb, Jr. -

Bay Crossing Study Public Comments 5-1-2018 to 5-31-2018 Letters

Below is one of two traffic-flow graphics currently shown at the public information meetings being held by the Chesapeake Bay Crossing Study Blatantly Wrong! conducted by the Maryland Transportation Authority (MDTA). (Note the callouts added to the graphic in red.) MDTA placed Queen Anne’s, Note that MDTA placed Anne Arundel Talbot and Caroline Counties far north of the Bay Bridge even County well north of the Bay Bridge Actual position of Actual position of though the bridge is actually with no direct connection to the Anne Arundel County bridge even though the bridge is Queen Ann’s County located in Queen Anne’s County. actually located in Anne Arundel Actual position of And both Talbot and Caroline County. Talbot and Caroline Counties lie well south of the Counties bridge. Note the actual location of Maryland counties relative to the actual location of the Look at the map! Bay Bridge. The MDTA graphic (top) is blatantly wrong and appears to have been designed to mislead viewers into believing that most of traffic flows to and from counties north of the Bay Bridge. This deceptive graphic appears as though it is intended DC to justify the construction of a new bridge north of the current VA one. MDTA positioned the counties into which the bulk of the traffic flows north of the bridge. Look at the map!This is DE fraudulent. As the percentages of flow clearly show, in non- summer months most of the travel flows between the two counties at either end of the bridge. Most of the traffic that continues through these two counties flows south of the Bay Bridge. -

PURPOSE and NEED 1.1 INTRODUCTION the Maryland

PURPOSE AND NEED 1.1 INTRODUCTION The Maryland Transportation Authority (MDTA), in coordination with the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), has initiated the Chesapeake Bay Crossing Study: Tier 1 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), referred to as the “Bay Crossing Study.” As announced by Governor Larry Hogan in 2016, the Bay Crossing Study is the critical first step to begin addressing existing and future congestion at the William Preston Lane Jr. Memorial (Bay) Bridge and its approaches along US 50/US 301. The study encompasses a broad geographic area, spanning nearly 100 miles of the Bay from the northern-most portion of the Bay in Harford and Cecil counties to the southern border with Virginia between St. Mary’s and Somerset counties (Figure 1). 1.1.1 The Tiered NEPA Process This two-tiered NEPA study will follow formal regulatory procedures in accordance with the Council on Environmental Quality and FHWA NEPA regulations resulting in preparation of a Tier 1 Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). A tiered environmental review process is being undertaken due to the regional needs to be addressed by the proposed action, influence of the Bay Crossing from both an environmental and socio-economic perspective, and expansive size of the study’s geographical area. Throughout both tiers of this analysis, previous studies assessing potential Bay crossings, such as the 2004 Transportation Needs Report, 2005 Task Force Study and 2015 Life Cycle Cost Analysis Study will be taken into consideration as appropriate. Tier 1 The Tier 1 NEPA Study represents the MDTA’s first step within a two-tiered NEPA approach and includes a high-level, qualitative review of engineering and environmental data. -

Commercial User Guide Page 1 FINAL 1.12

E-ZPass Account User Guide Welcome to the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission’s E-ZPass Commercial Account program. With E-ZPass, you will be able to pass through a toll facility without exchanging cash or tickets. It helps ease congestion at busy Pennsylvania Turnpike interchanges and works outside of Pennsylvania for seamless travel to many surrounding states; anywhere you see the purple E-ZPass sign (see attached detailed listing). The speed limit through E-ZPass lanes is 5-miles per hour unless otherwise posted. The 5-mile per hour limit is for the safety of all E-ZPass customers and Pennsylvania Turnpike employees. If you have any questions about your E-ZPass account, please contact your company representative or call the PTC E-ZPass Customer Service Center at 1.877.PENNPASS (1.877.736.6727) and ask for a Commercial E-ZPass Customer Service Representative. Information is also available on the web at www.paturnpike.com . How do I install my E-ZPass? Your E-ZPass transponder must be properly mounted following the instructions below to ensure it is properly read. Otherwise, you may be treated as a violator and charged a higher fare. Interior Transponder CLEAN and DRY the mounting surface using alcohol (Isopropyl) and a clean, dry cloth. REMOVE the clear plastic strips from the back of the mounting strips on the transponder to expose the adhesive surface. POSITION the transponder behind the rearview mirror on the inside of your windshield, at least one inch from the top. PLACE the transponder on the windshield with the E-ZPass logo upright, facing you, and press firmly. -

The E to Z of E-Zpass at the CBBT

How Your Transponder Works E-ZPass Account Replenishment CBBT’s 30/30 Discount Class If you are experiencing problems with your E-ZPass account, please contact E-ZPass at one of the following 1.As you pass through a toll lane, your E-ZPass During this time, when many businesses are closed 30 one-way trips/30 days locations: transponder is read in the read zone, which is to the public as a result of COVID-19, automatic In January, 2014, the CBBT implemented a 30/30 10-15 feet prior to the toll booth. replenishment with a credit or debit card is by far discount class, or “commuter” rate. This toll rate of Delaware Account Holders New Jersey Account Holders $6.00 each way is available to users who make 30 2.Instantly, the transponder is read by an antenna. the most popular way to manage your E-ZPass ac- 1.888.397.2773 1.888.288.6865 count. However, here are a number of manual re- one-way trips across the CBBT within a 30-day www.ezpassde.com www.ezpassnj.com The proper toll is deducted from your pre-paid period, utilizing the same E-ZPass transponder E-ZPass Account. At the CBBT, if you are making plenishment options available as well: for all 30 trips. Florida Account Holders New York Account Holders a return trip that qualifies for any toll discount, you Use a credit or debit card or ACH. Log onto your ac- How it Works: (Central FL Expressway only) 1.800.333.8655 do not need to do anything special. -

Interior Department” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 69, folder “Interior Department” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 69 of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR and Mrs. Thomas S. Kleppe cordially invite you to attend a reception and preview of the DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR'S BICENTENNIAL ART EXHIBITION AMERICA 1976 at the Corcoran Gallery of Art Washington, D.C. Monday, April26, 1976 6 to 8 P.M. Black tie optional Some items in this folder were not digitized because it contains copyrighted materials. Please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library for access to these materials. The Department of the Interior has commissioned 45 artists in an ambitious project that has proved the wisdom of government's direct involvement in art and has provoked a new look at the magnificence of the American land l Painting the public lands by Kay Larson hopes about government's direct in volvement in art.